Introduction

If you have been working through the accompanying web program, you will now have your research question (an actual one or a virtual one) and included it as part of your research proposal. Now that you know what you are going to explore, you need to check if anyone has done something similar and, if so, what their findings are, as this will have an impact on your own research. After all, you do not want to find yourself repeating what someone has already done. In order to discover what has been researched and published, you have to review it in order to assess its value to your research study.

This chapter provides a guide to the principles of searching and reviewing the research literature.

- It introduces you to the hierarchy of evidence which will assist you in deciding the level and merit of the evidence.

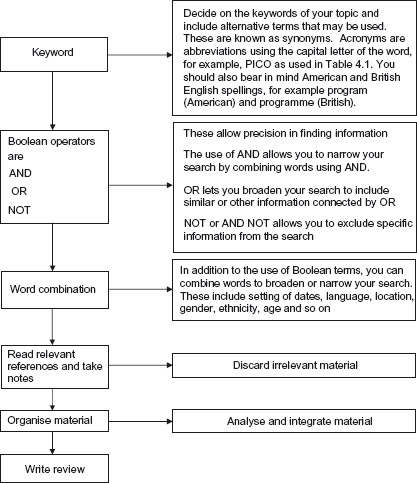

- Conducting a literature search can be a lengthy and complex process; however, the time and effort that you expend on this is well worth the investment (Hart 1998). Undertaking a good, sound and relevant literature search and review of that literature demands an organised and systematic approach, so it is very important to keep detailed records of the searches made and the information found. Figure 4.1 provides guidance on searching the literature.

- Later, this chapter introduces you to the steps you need to take in appraising and reviewing the literature that you find.

- The chapter concludes with an activity for you to undertake.

Steps in searching the literature

To help you to understand this chapter, you may wish to use the question that you developed for the activity at the end of chapter 3. You should work through the procedures using your own question.

The flow diagram depicted in Figure 4.1 below takes you through the steps you need to undertake in order to identify and access the relevant published (and other) literature. When you read the next section, you will appreciate that searching the literature is very similar to researching your research question. There is a very good reason for this – you generally need to have undertaken a literature search in order to finalise your research question. So, finalising your research question and undertaking a literature search are simultaneous tasks that you need to carry out when writing a research proposal.

Figure 4.1 Steps in the literature search. Adapted from Hart (1998) , Burns & Grove (2003) , Polit & Beck (2004).

There are many sources that you can turn to in order to undertake a literature search and these are listed below (see also chapter 3).

- Peer-reviewed journals: include research – based articles in their publication range.

- Government publications: include funded research reports, discussion papers, conference proceedings, government policies and enquiry results.

- Organisations and professional bodies.

- Indexes and abstracts to theses.

- Reference collections: on past students’ work, dictionaries.

- Conference proceedings.

- Pharmaceutical company information.

- Discussion and networking groups.

- Newspapers.

How to undertake a literature search

In undertaking a literature search, you will quickly become aware that there is a large – almost overwhelming – body of literature and other resources, both published and unpublished, you can call on for background information and evidence of relevance to your proposed research study.

When you come to search the literature, the first things that you need to have to hand are ‘key words’ – words that encapsulate what your research is about. For example, let us suppose that you are going to undertake research into the incidence and causes of falls in the elderly. So, all your key words will need to be linked to the concept of falls in the elderly. Your key words will therefore comprise:

Falls

Elderly

These are the words that you will put into your database (see chapter 3).

We also have to consider synonyms. These are words/phrases that have identical or very similar meanings For example, a synonym for ‘falls’ that you might wish to consider is ‘tumbles’. Why is this important? Well, there may be some literature discussing falls in the elderly that does not use the word ‘falls’, but rather talks about tumbles in the elderly, so if you only enter the word ‘falls’ in your database, these papers will be missed. Consequently, you need to think about synonyms for all the terms that you entered into the database and enter these as well.

As well as synonyms, you may want to note alternative spellings and acronyms for use in your search.

As mentioned above, you may find there is a mass of information available, although this does depend on how much research has been done in the area you are searching. If you find that there is so much information that you cannot access or assess it all, you will need to narrow your search to obtain a manageable number of articles. We shall return to this later in this chapter when we look at inclusion and exclusion criteria. But for the moment, we are still trying to access as much information as possible, and to help in this, rather than do one search for ‘falls’, and then a second search for ‘tumbles’, followed by a third for ‘elderly’, and perhaps yet another search for ‘aged’ (a synonym for elderly), we can combine them by using ‘Boolean operators’. These are terms such as ‘AND’, ‘OR’, ‘NOT’ which are inserted between our keywords and synonyms.

For example, if we are looking for literature to do with falls in the elderly (but excluding the elderly who suffer a fall because of a stroke), we could insert into our database ‘falls OR tumbles AND elderly OR aged NOT strokes’. This will give us all the literature that includes the first four terms, but excludes ‘stroke’. Try this combination using the CINAHL database. You will be surprised at the huge number of positive results you get (these are also known as ‘hits’).

You can combine words without Boolean operators (see Figure 4.1), but this is not usually as effective.

You can also refine your search by reviewing the literature in relation to some of the main themes pertinent to your topic. For example, if you are looking for literature about hypertension, you will need to bear in mind a definition of mild hypertension. You may wish to use the British Hypertensive Society’s guidelines or any other suitable definition. You may also want to specify which type of medication you would like to find evidence about. These should be noted.

If, as is quite probable, you receive thousands of hits, then you have to find some way of reducing the number. So, you need to set parameters, such as by having inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria are characteristics that are essential to the problem under scrutiny (Polit & Beck 2004). They are sometimes referred to as eligibility criteria; in other words, the sample population must possess the characteristics. Examples of inclusion or eligibility criteria include:

- appropriate age groups (e.g. for our example, you may want to have an inclusion criterion that includes only those over the age of 75 years);

- Language (e.g. English);

- location (e.g. Europe, the UK, England, Manchester);

- period (e.g. 2000–10);

- (possibly) evidence-based medicine.

The inclusion criteria of evidence-based medicine will mean that the results of the search will be limited to articles reviewed in databases such as Health Technology Assessment (HTA), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and Databases of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE). DARE complements the CDSR by providing a selection of quality assessed reviews in those subjects where there is currently no Cochrane review (Greenhalgh 1997, Polit & Beck 2008).

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria are the opposite of inclusion criteria and are characteristics that you specifically do not wish to include in your search, such as Caucasians with diabetes if the problem pertains to Afro-Caribbean males with diabetes.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are important characteristics of a research study as they have implications for both the interpretation and generalisability of the findings (Polit & Beck 2008).

Having obtained the literature, you will need to decide on the relevance of the material found. This can be done by assessing it using a hierarchy of evidence or by reviewing the literature using the research process.

Hierarchy of evidence

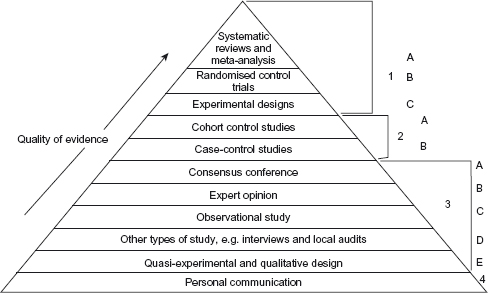

The hierarchy of evidence is an aid that we commonly use to assess the value of the material found, and is used in clinical decision-making (Table 4.1). Hierarchies of evidence were first used by the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination in 1979, and have subsequently been developed and used in assessing the effectiveness of research studies (Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination 1979, Sackett 1986, Cook et al. 1995, Guyatt et al. 1995, Petticrew & Roberts 2003). Thus, the hierarchy of evidence allows research-based evidence to be graded according to their design, is ranked in order of decreasing internal validity (National Health Service for Reviews and Dissemination 1996) and indicates the confidence decision- and policy-makers can have in their findings. However, the hierarchy of evidence remains contentious when applied to health promotion and public health (Petticrew & Roberts 2003 ).

Briefly, the hierarchical levels of evidence are shown in Table 4.1. (See chapter 5 for more information on these types of research studies and other evidence-based studies.)

There is much unresolved controversy about the kind of evidence that is most relevant to practice-particularly nursing practice and other health professional practice, with the exception of doctors (although many doctors are now seeing the value of ‘lower-level’ evidence within the sphere of caring for patients and clients). Although there is an undeniable need for quantitative research, this approach is not suitable for many issues encountered in nursing practice (Polit & Beck 2008). Patients’ views about healthcare are not always quantifiable – for example, their experience of living with a long-term condition, the effects of treatment or their choice of treatment. These views need to be considered when delivering healthcare when the concept of a hierarchy of evidence is often problematic when appraising the evidence for social or public health interventions. Indeed, the involvement of patients and their views are actively encouraged in all nursing and other health professional research projects these days. These issues cannot be addressed appropriately in a quantitative study; a qualitative approach is suitable as this way of conducting research focuses on the meanings and understandings of people’s experiences (Burns & Grove 2003).

Table 4.1 Hierarchy of evidence.

| Level | Evidence |

| 1. | A Systematic reviews/meta – analyses |

| B Randomised control trials (RCTs) | |

| C Experimental designs | |

| 2. | A Case control studies |

| B Cohort control studies | |

| 3. | A Consensus conference |

| B Expert opinion | |

| C Observational study | |

| D Other types of study, e.g. interviews, local audits | |

| E Quasi-experimental, qualitative design | |

| 4. | Personal communication |

Another way of demonstrating the hierarchy of evidence is by means of a triangle (Figure 4.2), with the systematic reviews at the top because they are considered to be the strongest evidence, whilst personal communication is considered to be the weakest evidence and so is placed at the bottom. However, although contentious, it may be possible to argue that in terms of healthcare, the hierarchy of evidence triangle should be inverted (turned upside down) because personal communication and qualitative care are concerned with patient care from the patients’ point of view, and therefore this evidence should be placed at the apex. In this scenario, objectivity does not apply to the perceptions that patients and other service users (e.g. family members) have of the care given by a healthcare professionals and healthcare organisations.

This is highly subjective, but it is something for you to consider when undertaking your evaluation of the literature you have found. (The triangle follows the classifications found in Table 4.1.)

Another way of deciding on the worth of the material is by reviewing and/or appraising the evidence guided by a systematic process. A number of factors are important when adopting this process and these are considered next.

Figure 4.2 The hierarchy of evidence triangle.

Table 4.2 An example of the hierarchy of evidence.

(Source: Booth, A. and O’Rourke, A., Hierarchy of Evidence In: Systematic Reviews: What are they and why are they useful? [Online Module]. University of Sheffield, 1998. Available at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/scharr/ir/units/systrev/hierarchy.htm)

| Rank | Methodology | Description |

| 1 | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses | Systematic review: review of a body of data that uses explicit methods to locate primary studies, and explicit criteria to assess their quality. Meta-analysis: A statistical analysis that combines/integrates the results of several independent clinical trials considered by the analyst to be ‘combinable’, usually to the level of reanalysing the original data, also sometimes called pooling, quantitative synthesis. Both are sometimes called overviews. |

| 2 | Randomised controlled trials (finer distinctions may be drawn within this group based on statistical parameters such as confidence intervals) | Individuals are randomly allocated to a control group or a group that receives a specific intervention. In other respects the two groups are identical for any significant variables. They are followed up for specific end points. |

| 3 | Cohort studies | Groups are selected on the basis of their exposure to a particular agent and followed up for specific outcomes. |

| 4 | Case-control studies | ‘Cases’ with the condition are matched with ‘controls’ without it, and a retrospective analysis used to look for differences between the two groups. |

| 5 | Cross-sectional surveys | Survey or interview of a sample of the population of interest at one point in time |

| 6 | Case reports | A report based on a single patient or subject; sometimes collected into a short series |

| 7 | Expert opinion | A consensus of experience from ‘the good and the great’ |

| 8 | Anecdotal | Something your friend told you after a meeting |

Reviewing the literature

This is linked to the Literature section of the web program.

When undertaking research it is important to know what has been written about the topic you wish to investigate by undertaking a literature review. A literature review critically summarises the current knowledge in the area under investigation, identifying the strengths and weaknesses of previous research and knowledge. It provides the context within which you can place your own study (Hart 1998).

Undertaking a literature review requires developing a complex set of skills through practice. This means that you are planning your own research study and organising your time-line (your plan of how much time you can give to the research and how it is to be divided into the various aspects of the study). You will need to allocate enough time to obtain and read the relevant literature and assess its quality. By reading and assessing different studies, you will begin to gain an impression of the important aspects of your proposed topic. These include:

- identifying data sources other researchers have used;

- the style of writing;

- identifying the relationship between concepts in your area of study;

- ideas for further consideration;

- how you can avoid repeating other researchers’ errors as well as duplicating previous work.

In addition, you will begin to develop your own reading strategy, as well as your own planning and writing strategies (Hart 1998).

Undertaking a comprehensive review of the literature is particularly important because it:

- provides you with an up-to-date understanding of the subject and its significance to practice;

- identifies the methods used in previous research and therefore ones that you could possibly use – or avoid using – in your own research study.

- helps you to formulate potential research topics, questions and the future direction of your investigation;

- provides you with a basis on which your subsequent research findings can be compared (Gray 2004 ).

You may also be able to identify the significant personalities in your area of interest – the leaders in the field who have undertaken and published exceptional research in this field, on whom, perhaps, you could ‘bounce’ your ideas.

Also from the literature you can begin to find out whether any diverse or conflicting viewpoints exist, as well as the aspects of the topic under investigation that have produced significant discussion. Any conflicting viewpoints may arise from differing interpretations of various theories within the same topic. You need to be aware of these interpretations as well as the arguments supporting the theories in order to assess their value and make up your own mind about their merit, relevance and importance, particularly with regard to your proposed research topic and study. All of this will enable you to begin to develop some general explanations for observed variations in behaviour or phenomena that you may be able to elicit/identify in your own research study.

Steps in reviewing the literature

Previously, you have been shown how to identify and obtain the relevant literature – relevant, that is, to your proposed study and to the topic in general. Having obtained this, the next step is to review this literature.

There are a number of ways in which the literature can be reviewed. An important task for the reviewer is to summarise the research papers and to identify and discuss the main studies that have been published in your field of interest. A number of writers (e.g. Grbich 1999, Burns & Grove 2003, Polit & Beck 2008) suggest that a review of the literature can be divided into several sections. The subdivisions discussed here are an adaptation of ideas and writings from these authors. Using the subdivisions and considering the points suggested will assist in this activity. However, you are going to have to understand each report as a whole in order to get a sense of what it is about. These divisions are like the individual bricks in a wall or the single steps in a journey – they are only a part of the picture. It is important to appreciate the wall or the journey as a total experience; the bricks/steps are a way of allowing you to do this.

The structure of the report

- Is the organisation of the report logical? Does it make sense/is it understandable?

- Does the report follow a sequence of steps of the process of research, such as these?