Introduction

We continue with the research process by addressing the research question or problem to be investigated. From now on, the chapters are linked very closely to the web program, and so to get the most out of this book you should read the relevant section of the web program alongside the chapters.

In this chapter we concentrate on the development of a research question. This is followed by a discussion of types of questions.

Developing the research question

It is impossible to overstate just how important it is for you to start your research journey with a firm, sensible, clear, concise, relevant and achievable research question or problem. That is the focus of this chapter.

Important features of a good question include the following. It should:

- be about one issue – if you attempt to undertake more than one, then your research will become very complicated and you will lose rigour and credibility with it;

- be clear and concise – if your research question is not, you and everybody who comes into contact with, or reads, your research will struggle to make sense of what you are attempting to investigate;

- address an important, controversial and/or an unresolved issue– there is no point in repeating research, unless you are attempting to verify previous research;

- be feasible within a specified time-frame – you need to work out how much time you have available for your research and tailor your question so that you know that it can be answered within that period;

- be adequately resourced – you need to know that you have the resources to enable you to finish your research. Therefore, your research question has to be developed so that you are sure from the outset that you have all the resources necessary to carry out the research.

However, at this point we need to stress that, in developing your research question and undertaking your research, of crucial importance is your interest or, better, your passion, in the topic. So, it is essential that your research is focused on an area or subject where you are confident that your interest/passion will not flag during the often long periods you will need to devote to it.

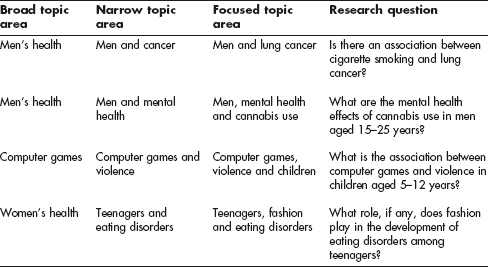

How do you go about developing a research question? You may be very familiar with the area in which you wish to undertake research, but how do you narrow it down to just one question? Table 3.1 (below) offers an example of where to begin. Initially, it is advisable to formulate several questions related to your research area so that you can choose the one that best suits your interests and circumstances. This could be seen as the first stage in the hour glass notion of research identified in Figure 3.1, where you begin with broad questions. Your question may be derived from the patient’s problem or condition.

Questions arising from the patient’s condition

So, after this brief diversion, we can now return to the first stage of research, namely writing a research question.

This stage consists of:

In order to think about these two stages, let us use as an example an aspect of a patient’s condition or treatment.

When nursing a patient it is not unusual for you to consider why the patient is being cared for in a particular way or whether there is an alternative. How would you answer your concern or problem? One of the points that you need to be clear about is the question that you want to ask. This may not be as easy as it sounds, because if you do not ask the right type of question, you will not get the correct answer. Before we continue, you have to be aware that the answer that you receive from your research study may not be what you expected, or even what you wanted, yet your research may still have been successful. In all cases, however, the answer must be related to the original research question; if not, the research can be deemed to have failed.

Table 3.1 Developing the research question.

Let us take a closer look at the types of questions that may arise during your consideration of a problem you have identified.

Types of question

You will need to decide on the type of information you require as this will help you to formulate the question that needs to be asked.

There are two types of questions: background questions and foreground questions (McKibbon&Marks 2001).

The broad, narrow and focused topic areas can be seen as the first and second stages of the hourglass analogy of research.

1. Background questions

This is the first stage of forming a question, and these background questions allow you to find out more about the patient, problem or condition under investigation. These are questions about:

- Who?

- What?

- When?

- Where?

- Why?

- How?

and are related to the problem.

An example of such a background question is:

- What causes backache?

Note that there are no inclusion or exclusion criteria and a search of the literature for this question would produce a large quantity of information that might be helpful in assisting with your focused question(s). Thus, background questions give basic information about the condition and may help you to formulate the specific or foreground questions.

2. Foreground questions

Unlike background questions, foreground questions ask for specific information about managing the patient or problem (McKibbon&Marks 2001 ).

Foreground questions can be related to:

- Diagnosis: this includes selecting the most appropriate diagnostic test or interpreting the results of a particular test.

- Treatment: here you may look at what the most effective treatment is, given a particular clinical problem.

- Harm or aetiology: this takes us into the realms of what the harmful effects of a particular treatment are and how can they be minimised or reduced.

- Prognosis: under this heading, we can look at what the likely course of the disease is in this patient or group of patients.

- Service redesign: this type of question is moving away from the individual patient and exploring systems and processes. These types of questions have a profound impact on the individual patient. An example of a possible research question is: is it cost-effective to move the care of patients with chronic respiratory conditions from secondary to primary care?

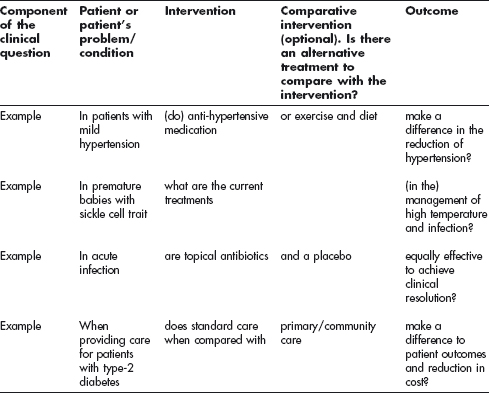

Sackett et al. (1997) devised a framework which can be used to ask foreground questions:

Patient or Problem, Intervention, Comparative intervention and Outcome (PICO).

In some cases there may be a comparative intervention (i.e. drug trials, where you are comparing a new drug with the status quo treatment), but this is not always the case. Table 3.2 provides an example of how PICO can be used. All this relates to the second stage of the hourglass model (see Figure 3.1), that is, to the narrow question by being more focused on identifying exactly what you want to find out.

It is important at this stage to note that none of the above forms part of the research proposal. Only the final question/problem that you have decided that you want to explore will appear on the research proposal. However, all that we have just been discussing will help you to settle on the question or problem that you wish to explore in your research study, and that is a question or problem that will appear as part of your research proposal (see the web program).

Table 3.2 Components of foreground questions using PICO.

Now you have devised your question, the next step is to locate the sources that are available to arrive at the answer. This forms the second aspect of the questions arising from the patient’s condition and is discussed next.

Finding the answers to your questions

A number of resources may be at your disposal. For a start, you could consult a clinical nurse specialist or a nurse consultant, if there are any in your hospital or clinic. You may also consider consulting the ‘knowledge manager’ or ‘information consultant’ at your learning resources centre, who may be able to direct you to specialist journals as well as to specialist databases such as Medical Literature On-line (Medline) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) in order to help you to find sources that are relevant to your proposed research study. You should also consider searching the web for information about your topic.

Other sources include:

- Peer-reviewed journals: these include research-based articles. These should provide enough details about the methodology employed so that you can make an informed judgement about the study’s validity and the clinical relevance of the findings (see chapter 4 and the web program).

- Government publications: include funded research reports, discussion papers, conference proceedings, government policies and enquiry results.

- Organisations and professional bodies: these often provide free information as well as providing you with further sources of evidence.

- Indexes and abstracts to theses: these are often to be found in the libraries of your local Higher Education Institute or your hospital library; if not, all are available from the British Library.

- Reference collections: on past students’ work, dictionaries and encyclopaedias.

- Conference proceedings – check journals which often publish special editions linked to conferences.

- Pharmaceutical company information – to access this, it is useful to get to know your local drug representatives, as well as visiting drug company stands at conferences. These often have copies of research papers linked to their products.

- Discussion and networking groups – sources here include the Internet and local/national nurse/health professional groups (e.g. the Royal College of Nursing).

- Newspapers – however, if possible, do search for the original source of the article.

You may find yourself becoming swamped with information, depending on how much research has been done in the area you are researching. If this is the case, you will need to narrow your search to obtain a manageable number of articles.

When you are reading research articles you will notice that some research studies pose a direct question as shown in Table 3.1 above, but other research studies may make a statement; this is referred to as a hypothesis and forms the discussion of the next section.