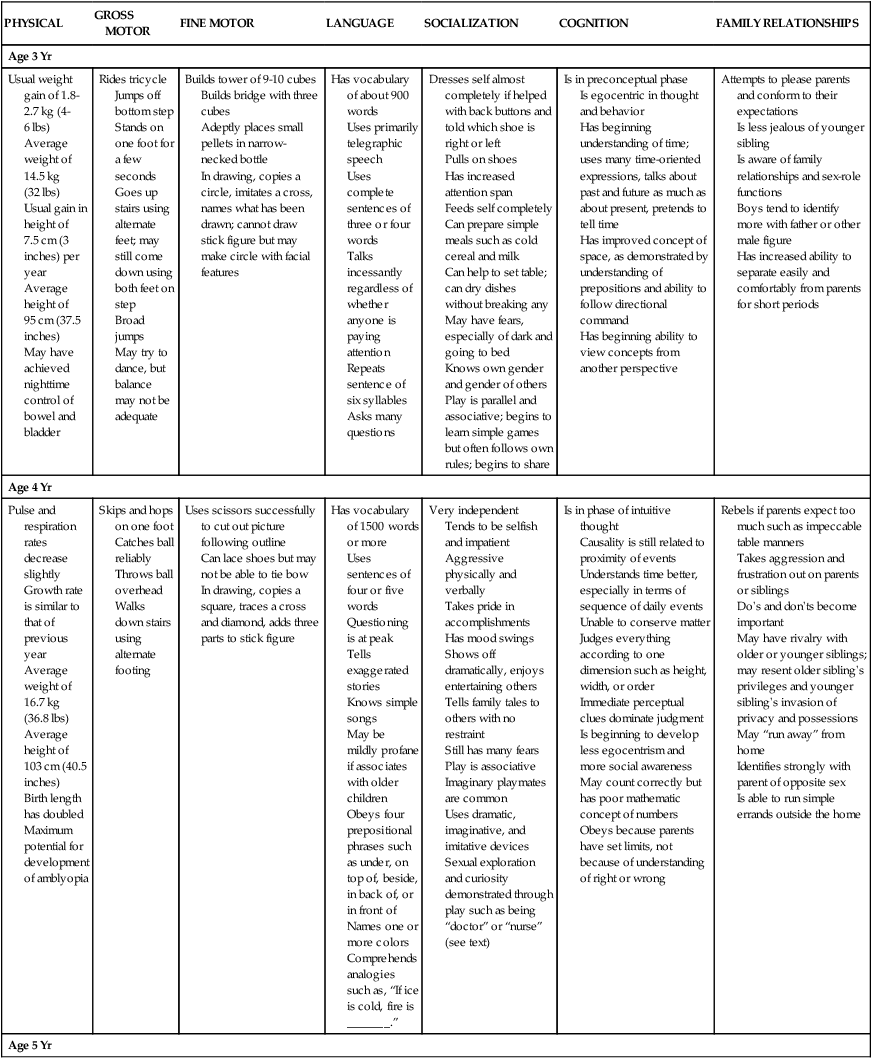

Chapter 33 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify the major biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, moral, spiritual, and social developments that occur during the preschool years. • List the benefits of imaginary playmates. • Prepare preschoolers for preschool or day care experience. • Provide parents with guidelines for sex education. • Provide parents with guidelines for dealing with a child’s fears, stresses, aggression, and sleep problems. • Recognize the causes of stuttering during the preschool years. • Offer parents suggestions for preventing speech problems. • Recognize feeding patterns of preschoolers. • Provide anticipatory guidance to parents regarding injury prevention based on the preschooler’s developmental achievements. Walking, running, climbing, and jumping are well established by age 36 months. Refinement in eye-hand and muscle coordination is evident in several areas. At age 3 the preschooler rides a tricycle, walks on tiptoe, balances on one foot for a few seconds, and broad jumps. By age 4 the child skips and hops proficiently on one foot (Fig. 33-1) and catches a ball reliably. By age 5 he or she skips on alternate feet, jumps rope, and begins to skate and swim. After preschoolers have mastered the tasks of the toddler period, they are ready to face the developmental endeavors of the preschool period. Erikson (1963) maintained that the chief psychosocial task of this period is acquiring a sense of initiative. Children are in a stage of energetic learning. They play, work, and live to the fullest and feel a real sense of accomplishment and satisfaction in their activities. Conflict arises when they overstep the limits of their ability and inquiry and experience a sense of guilt for not having behaved appropriately. Feelings of guilt, anxiety, and fear may also result from thoughts that differ from expected behavior. Development of the superego, or conscience, begins toward the end of the toddler years and is a major task for preschoolers (see Cultural Competence box). Learning right from wrong and good from bad is the beginning of morality (see section on Moral Development). Development of the conscience is strongly linked to spiritual development. At this age children are learning right from wrong and behaving correctly to avoid punishment. Wrongdoing provokes feelings of guilt, and preschoolers often misinterpret illness as a punishment for real or imagined transgressions. Observing religious traditions and participating in a religious community can help children cope during stressful periods such as illness and hospitalization (Speraw, 2006). In many religious faiths cultural practices and religion are closely intertwined (McEvoy, 2003) and are an important part of the child’s and family’s life. The preschool years play a significant role in the development of body image. With increasing comprehension of language, preschoolers recognize that individuals have desirable and undesirable appearances. They recognize differences in skin color and racial identity and are vulnerable to learning prejudices and biases. They are aware of the meaning of words such as pretty or ugly, and they reflect the opinions of others regarding their own appearance. By 5 years of age children compare their size with that of their peers and can become conscious of being large or short, especially if others refer to them as “so big” or “so little” for their age. Research indicates that girls as young as preschool age already show concern about appearance and weight (Skouteris, McCabe, Swinburn, et al., 2010). Because these are formative years for both boys and girls, parents should make efforts to instill positive principles regarding body image, give their children encouraging feedback regarding their appearance, and emphasize the importance of accepting individuals no matter how their appearances differ. Children at this age should be educated regarding the benefits of physical activity and nutrition on health rather than focusing on weight. During the preschool years language becomes more sophisticated and complex and the major mode of communication and social interaction (Fig. 33-2). Through language preschool children learn to express feelings of frustration or anger without acting them out. Both cognitive ability and environment—particularly consistent role models—influence vocabulary, speech, and comprehension. Vocabulary increases dramatically, from 300 words at age 2 years to more than 2100 words at the end of 5 years. Sentence structure, grammatic usage, and intelligibility also advance to a more adult level. Language development during these early years predicts school readiness (Harrison and McLeod, 2010) and sets the stage for later success in school (Reilly, Wake, Ukoumunne, et al., 2010). Children between the ages of 3 and 4 years form sentences of about three or four words and include only the most essential words to convey a meaning. Such speech is often termed telegraphic for its brevity. Three-year-old children ask many questions and use plurals, correct pronouns, and the past tense of verbs. They name familiar objects such as animals, parts of the body, relatives, and friends. They can give and follow simple commands. They talk incessantly regardless of whether anyone is listening or answering them. They enjoy musical or talking toys or dolls and imitate new words proficiently. Preschoolers also benefit from “reading” picture books with a parent or adult figure; this provides immediate feedback to the child and helps develop vocabulary as he or she hears the pronunciation of words from an adult (Feigelman, 2011). There is evidence that reading and speaking to a child in early life programs words into the child’s memory bank for use at a later time. From ages 4 to 5 years preschoolers use longer sentences of four or five words and more parts of speech to convey a message (e.g., prepositions, adjectives, and a variety of verbs). They can follow simple directional commands such as, “Put the ball on the chair,” but can carry out only one request at a time. They answer questions such as, “What do you do when you’re hungry?” by describing the appropriate action. The pattern of asking questions is at its peak, and children usually repeat a question until they receive an answer. Preschoolers also are incapable of understanding figurative speech and are very literal in their understanding of the meaning of words (Feigelman, 2011). For example, saying that an IV cannula to be inserted for hydration is a straw is interpreted by the preschooler as literally a drinking straw because that is his or her common frame of reference for that object. The pervasive ritualism and negativism of toddlerhood gradually diminish during the preschool years. Although self-assertion is still a major theme, preschoolers demonstrate their sense of autonomy differently. They are able to verbalize their request for independence and perform independently because of their much-refined physical and cognitive development. By 4 or 5 years of age they need little if any assistance with dressing, eating, or toileting (Fig. 33-3). They can be trusted to obey warnings of danger, although 3- or 4-year-old children may exceed their boundaries at times. They are also much more sociable and willing to please. They have internalized many of the standards and values of the family and culture. However, by the end of early childhood they begin to question parental values and compare them with those of their peer group and other authority figures. As a result they may be less willing to abide by the family’s code of conduct. Preschoolers become increasingly aware of their position and role within the family. Although this is a more secure age for experiencing the addition of another sibling, relinquishing the position of first or youngest is still difficult and requires appropriate preparation (see Sibling Rivalry, Chapter 32). Play activities for physical growth and refinement of motor skills include jumping, running, and climbing. Tricycles, wagons, gym and sports equipment, sandboxes, wading pools, and activities at water parks can help develop muscles and coordination (Fig. 33-4). Activities such as swimming and skating teach safety and muscle development and coordination. Children involved in the work of play do not require expensive toys and gadgets to keep them entertained but often enjoy playing with common household items such as a broom handle or even items that adults consider junk (boxes, sticks, rocks, and dirt). The imaginative mind of the preschooler enjoys playing for play’s sake. Probably the most characteristic and pervasive preschool activity is imitative, imaginative, and dramatic play. Dress-up clothes, dolls, housekeeping toys, dollhouses, play store toys, telephones, farm animals and equipment, village sets, trains, trucks, cars, planes, hand puppets, and medical kits provide hours of self-expression (Fig. 33-5). Probably at no other time is the reproduction of adult behavior so faithful and absorbing as in 4- and 5-year-old children. Toward the end of the preschool period children are less satisfied with make-believe or pretend objects and enjoy doing the actual activity such as cooking and carpentry. Television and other media also have their place in children’s play, although each should be only one part of children’s total repertoire of social and recreational activities. Parents and other caregivers should supervise the selection of programs, watch and discuss programs with their children, schedule limited time for television viewing, and set a good example of television viewing (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2007). Children enjoy and learn from educational programs; however, television viewing may limit time spent in other meaningful activities such as reading, physical activity, and socialization (AAP, 2007). Prolonged television viewing by young children has been linked to an increase in psychologic distress and decreased time spent in active playing, which increases the risk for obesity among certain children (Hamer, Stamatakis, and Mishra, 2009). Fast-paced television cartoons have been linked to a temporary decrease in executive functioning in 4-year-olds (self-regulation and working memory) (Lilard and Peterson, 2011). Although the potential negative effects of television viewing have been well documented in literature, research has also shown that prosocial behavior and later academic achievement can result from viewing educational media during the preschool years; however, positive effects depend on the media content, the age of the viewer, the length of viewing time, and the presence of a co-viewing parent (Kirkorian, Wartella, and Anderson, 2008). When parents view media with their children, the activity can become interactive, with parents and children discussing program content. Considering the significant increase in media accessibility through various portable electronic devices and cell phones, parents need to be aware of the potential positive and negative effects of media exposure. Play is so much a part of young children’s lives that reality and fantasy become blurred. Make-believe is reality during play and only becomes fantasy when the toys are put away or the dress-up clothes are removed. It is no wonder that imaginary playmates are so much a part of this age period. The appearance of imaginary companions usually occurs between 2½ and 3 years of age, and for the most part such playmates are relinquished when the child enters school. Differences in birth order and gender have been noted in studies of imaginary companion play. Firstborn children have a higher incidence of imaginary companions as do young girls; young boys more often tend to impersonate characters (Trionfi and Reese, 2009). Table 33-1 summarizes the major developmental achievements for children 3, 4, and 5 years of age. TABLE 33-1 GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT DURING PRESCHOOL YEARS Some children are home schooled, but many attend some type of early childhood program, usually preschool or a day care center. Group care has become commonplace with the large number of parents currently employed outside the home (see Alternate Child Care Arrangements, Chapter 31). The effects of early education and stimulation on children have increasingly gained recognition. (For a discussion of the effects of day care on young children, see Working Mothers, Chapter 27.) Because social development widens to include age mates and other significant adults, preschool provides an excellent vehicle for expanding children’s experiences with others. It is also excellent preparation for entrance into elementary school. One of the issues that parents face is their children’s readiness for preschool or kindergarten. There are no absolute indicators for school readiness; but children’s social maturity, especially attention span, is as important as their academic readiness. Using a developmental screening tool that addresses cognitive (especially language), social, and physical milestones can identify children who may benefit from diagnostic testing and early-intervention programs before starting school. Parents play an integral role in their children’s school readiness. They should promote a positive attitude toward learning, read to their children, encourage their children to participate in a variety of activities to explore their talents and interests, and choose appropriate child care or preschool programs (Hagan, Shaw, and Duncan, 2008). Nurses and other health care workers can guide parents in selecting enriched social and educational early-intervention programs, schools, and child care centers. Careful selection of early-childhood education is intrinsic to future learning and development. Licensed and regulated programs are mandated to abide by established standards, which represent minimum requirements and safeguards. Regulation is important to protect children from harm and promote the conditions essential for a child’s healthy development and learning. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) serves as the model for optimal care of small children.* Evaluation of the health practices of the facility is extremely important. Children in day care centers have more illnesses than those not in day care centers, especially gastrointestinal tract infections; respiratory tract infections; and hepatitis A, varicella-zoster virus, and cytomegalovirus infections (Nesti and Goldbaum, 2007). Nurses play an important role in infection control. Not only can they advise parents regarding the evaluation of the sanitary practices of a facility, but they can also take an active part in educating staff in measures to minimize transmission of infection (Fig. 33-6). Proactive infection control measures and education of staff have been effective in reducing the incidence of upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and rotavirus (Kotch, Isbell, Weber, et al., 2007). Day care staff should also have updated routine immunizations according to the adult immunization recommendations, including the annual influenza vaccine, to protect the children in the center (AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, 2012). Parents should inquire about the policy of the center regarding the attendance and care of sick children. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2012 Red Book: Report of the Committee of Infectious Diseases (2012) contains additional infection control guidelines regarding day care hand washing; cleaning sleep equipment, toys, and food; care of pets; and conditions or illnesses for which children should be kept out of day care to prevent the spread of illness. Many excellent books on sex education are available for preschool children at public libraries. The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS)* and the AAP† have bibliographies of suggested reading material. Parents should read the book themselves before giving or reading them to their children. To help parents deal with stress in their child’s life, they must be aware of its signs (see Stress in Childhood, Chapter 28) and be helped to identify the source. Any number of stressors may be present such as the birth of a sibling, marital discord, divorce and separation, relocation, or illness. Evidence indicates that types of aggression differ between genders. Boys exhibit more physical aggression than girls during preschool years (Benzies, Keown, and Magill-Evans, 2009); however, preschool girls exhibit more relational aggression than preschool boys (Ostrov and Bishop, 2008). Frustration, or the continual thwarting of self-satisfaction by disapproval, humiliation, punishment, or insults, can lead children to act out against others as a means of release. Especially if they fear their parents, these children displace their anger on others, particularly peers and other authority figures. This type of aggression often applies to children who are well-behaved at home but have a discipline problem at school or are bullies among their playmates. Modeling, or imitating the behavior of significant others, is a powerful influencing force in preschoolers. Children who see their parents as physically abusive are observing behavior that they come to know as acceptable and therefore may exhibit with others (Benzies, Keown, and Magill-Evans, 2009). Another aspect of modeling is the “double standard” for acceptable conduct. For example, in some families aggression is synonymous with masculinity, and boys are encouraged to defend themselves. Television is also a significant source for modeling at this impressionable age. Research indicates that there is a direct correlation between media exposure, both violent and educational media, and preschoolers exhibiting physical and relational aggression (Ostrov, Gentile, and Crick, 2006). Therefore parents should be encouraged to supervise television viewing. The AAP (2007) offers a list of recommendations for healthy television viewing. When children exhibit extreme behaviors such as aggression, parents may be concerned about the need for professional help. Generally the difference between “normal” and “problematic” behavior is not the behavior itself but its quantity (number of occurrences), severity (interference with social or cognitive functioning), distribution (different manifestations), onset (when behavior started), and duration (at least 4 weeks).* The most critical period for speech development occurs between 2 and 4 years of age. During this period children are using their rapidly growing vocabulary faster than they can produce the words. Failure to master sensorimotor integrations results in stuttering or stammering as children try to say the word about which they are already thinking. This dysfluency in speech pattern is common during language development in children 2 to 5 years of age (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, 2010). Stuttering affects boys more frequently than girls, has been shown to have a genetic link, and usually resolves during childhood (Prasse and Kikano, 2008). The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (2010) encourages parents and caregivers of children who stutter to speak slowly and relaxed, refrain from criticizing the child’s speech, resist completing the child’s sentences, and take time to listen attentively. The best therapy for speech problems is prevention and early detection. Common causes of speech problems include hearing loss or impairment, oropharyngeal structural anomalies, developmental disorders such as autism, brain injuries and other neuromotor impairments, lack of a verbally stimulating environment, and change in language exposure as in international adoption (Sharp and Hillenbrand, 2008). Referral for further evaluation and treatment may be necessary to prevent a problem from interfering with learning. Anticipatory preparation of parents for expected developmental norms may allay caregiver concerns. Healthy nutrition during childhood should include eating a variety of foods and consuming sufficient energy to promote growth and development while avoiding the development of obesity (AAP Committee on Nutrition, 2009). The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2010) recommend an average intake of 1400 to 1600 calories per day for a moderately active child 4 to 8 years of age; these guidelines emphasize the reduction of sugar-sweetened beverages and excess intake of juices for young children and an overall increase in the amount of whole grains, vegetables, and fruits.* A daily intake of 16 oz/day of milk for preschoolers is recommended; this can be whole milk, 2%, or 1% milk. The Dietary Guidelines indicate that there is moderate evidence that consumption of milk and other dairy products does not contribute significantly to weight gain in young children. Fluid requirements may also decrease slightly to approximately 100 mL/kg/day but depend on the child’s activity level, climatic conditions, and state of health. Protein requirements increase with age, and the recommended intake for preschoolers is 13 to 19 g/day (0.45 to 0.67 oz/day) (Otten, Hellwig, and Meyers, 2006). The AAP Committee on Nutrition (2009) recommends the following guidelines for children older than 2 years of age: saturated fatty acid consumption should be less than 10% of total caloric intake; total fat over several days should be 20% to 30% of total caloric intake; and cholesterol consumption should be less than 300 mg/day. Fiber intake for children 3 years of age should be 19 mg/day and 25 mg/day for children 4 to 8 years of age (AAP, 2009). Research supports the efficacy of following these recommendations, and negative health effects have not been reported (American Heart Association, Gidding, Dennison, et al., 2006). These efforts are important in preventing childhood obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. There is now sufficient evidence that the incidence of coronary heart disease, obesity, and chronic health problems such as diabetes mellitus can be influenced by early eating patterns (Barlow and Expert Committee, 2007). Evidence suggests that children who participate in family meal times in the home (three or more meals together) have a decreased risk for obesity and unhealthy eating patterns that may contribute to overweight and subsequent cardiovascular disease (Dattilo, Birch, Krebs, et al., 2012). In addition to limiting fat consumption, it is also important to ensure that diets contain adequate nutrients such as calcium. The recommendation for daily calcium intake for children 1 to 3 years of age is 500 mg; for children 4 to 8 years of age is it 800 mg (Otten, Hellwig, and Meyers, 2006). Milk and dairy products are excellent sources of calcium and vitamin D (fortified). Low-fat milk may be substituted; thus the quantity of milk may remain the same while limiting fat intake overall. Excessive consumption of fruit juices and other sweetened beverages has been associated with adverse health effects such as dental caries, gastrointestinal conditions such as chronic diarrhea, and diets poor in nutritive value (Allen and Myers, 2006). The AAP recommends limiting the intake of 100% fruit juice to 4 to 6 oz/day for children 1 to 6 years of age (AAP, 2009). Parents should be educated regarding nonnutritious fruit drinks, which usually contain less than 10% fruit juice yet are often advertised as healthy and nutritious; sugar content is dramatically increased and often precludes an adequate intake of milk by the child. When counseling parents regarding moderation in fruit juice consumption, providers should offer suggestions for more appropriate sources of nutrients such as ascorbic acid, folate, and potassium. In young children intake of carbonated beverages that are acidic or contain high amounts of sugar is also known to contribute to dental caries; large amounts of nonnutritive calories in such beverages may also displace or preclude intake of nutrients necessary for growth. An additional resource for dietary counseling includes MyPlate,* recently developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to replace MyPyramid. This colorful plate shows the five main food groups—fruits, grains, vegetable, protein, and dairy—with the intended purpose to involve children and their families in making appropriate food choices for meals and decrease the incidence of overweight and obesity in the United States. MyPlate provides an online interactive feature that allows the individual to select an individual food group and see choices for foods in that group. Approximate serving sizes are suggested, and vegetarian substitutions are also provided. This system is comprehensive and provides information for developing a healthy lifestyle at an early age. Parents can use this information to help their children make healthy lifestyle choices and prevent adverse health conditions secondary to poor nutrition. The importance of role-modeling by parents cannot be overemphasized in regard to food intake and dietary habits; if parents will not eat a particular food or if their dietary habits are poor, children are likely to develop the same habits. Some preschoolers still have food habits that are typical of toddlers such as food fads and strong taste preferences. When they reach 4 years of age, they seem to enter another period of finicky eating, which is generally characteristic of the more rebellious behavior of children in this age-group. As with toddlers, small portions of each item being served should be offered. The practice of having children remain at the table until the “plate is clean” should be avoided because this may contribute to overeating and the development of poor eating habits that contribute to poor health later in life. By 5 years of age children are more agreeable to trying new foods, especially if they are encouraged by an adult who allows them to help with food preparation or experiment with a new taste or different dish (Fig. 33-7). Mealtimes can become battlegrounds if parents expect perfect table manners.† Usually 5-year-old children are ready for the “social” side of eating, but 3- or 4-year-old children still have difficulty sitting quietly through long family meals. In addition to unhealthy eating habits, experts recognize that a sedentary lifestyle contributes to cardiovascular disease and obesity. Therefore the 2010 Dietary Guidelines also encourage 60 minutes of physical activity per day for children 6 years of age and older (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2010). One program recommends that preschoolers be encouraged to be involved in at least 2 hours of cumulative activity per 8-hour day in day care, including unstructured free playtime (Larson, Ward, Neelon, et al., 2011). Sleep patterns vary widely, but the average preschooler sleeps about 12 hours a night and infrequently takes daytime naps. Waking during the night is common throughout early childhood and may be related to social and environmental factors rather than developmental or physiologic causes (Moore, Meltzer, and Mindell, 2008). Motor activity levels continue to be high and allow preschoolers to explore their environment, begin learning physical games and sports, and interact with others. Sedentary activities such as television and video or computer games are increasingly appealing and can become unhealthy substitutes for active play. Preschoolers’ increased gross motor abilities and coordination allow them to engage in many physical activities, if only at a novice level. Whether young children should begin formalized training in an activity at this early age is controversial. Training programs must consider the child’s physical and psychologic immaturity, and readiness to participate in organized sports should be determined individually. The decision to participate should be based on the child’s, not the parent’s, motivation and enjoyment. The AAP Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness and the AAP Committee on School Health (2006) encourages free play and a variety of physical activities; however, the AAP also supports organized play when it is developmentally appropriate and occurs in a nonthreatening, fun, and safe environment. The preschool years are a prime time for sleep disturbances. Such disturbances are typically related to increasing autonomy, negative sleep associations, nighttime fears, inconsistent bedtime routines, and lack of limit setting (Moore, Meltzer, and Mindell, 2008). Sleep disturbances may also be caused by nightmares and sleep terrors. Consequences of inadequate sleep include daytime tiredness, irritability and other negative behaviors, hyperactivity, difficulty concentrating, impaired learning ability, poor control of emotions and impulses, and strain on family relationships (Mindell, Kuhn, Lewin, et al., 2006). Interventions differ greatly; for example, nightmares (frightening dreams that are followed by full arousal) and sleep terrors (partial arousal from deep, nondreaming sleep) require different approaches (see Table 32-2).

The Preschooler and Family

Promoting Optimal Growth and Development

Biologic Development

Gross and Fine Motor Skills

Psychosocial Development

Developing a Sense of Initiative (Erikson)

Spiritual Development

Development of Body Image

Social Development

Language

Personal-Social Behavior

Play

PHYSICAL

GROSS MOTOR

FINE MOTOR

LANGUAGE

SOCIALIZATION

COGNITION

FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS

Age 3 Yr

Usual weight gain of 1.8-2.7 kg (4-6 lbs)

Average weight of 14.5 kg (32 lbs)

Usual gain in height of 7.5 cm (3 inches) per year

Average height of 95 cm (37.5 inches)

May have achieved nighttime control of bowel and bladder

Rides tricycle

Jumps off bottom step

Stands on one foot for a few seconds

Goes up stairs using alternate feet; may still come down using both feet on step

Broad jumps

May try to dance, but balance may not be adequate

Builds tower of 9-10 cubes

Builds bridge with three cubes

Adeptly places small pellets in narrow-necked bottle

In drawing, copies a circle, imitates a cross, names what has been drawn; cannot draw stick figure but may make circle with facial features

Has vocabulary of about 900 words

Uses primarily telegraphic speech

Uses complete sentences of three or four words

Talks incessantly regardless of whether anyone is paying attention

Repeats sentence of six syllables

Asks many questions

Dresses self almost completely if helped with back buttons and told which shoe is right or left

Pulls on shoes

Has increased attention span

Feeds self completely

Can prepare simple meals such as cold cereal and milk

Can help to set table; can dry dishes without breaking any

May have fears, especially of dark and going to bed

Knows own gender and gender of others

Play is parallel and associative; begins to learn simple games but often follows own rules; begins to share

Is in preconceptual phase

Is egocentric in thought and behavior

Has beginning understanding of time; uses many time-oriented expressions, talks about past and future as much as about present, pretends to tell time

Has improved concept of space, as demonstrated by understanding of prepositions and ability to follow directional command

Has beginning ability to view concepts from another perspective

Attempts to please parents and conform to their expectations

Is less jealous of younger sibling

Is aware of family relationships and sex-role functions

Boys tend to identify more with father or other male figure

Has increased ability to separate easily and comfortably from parents for short periods

Age 4 Yr

Pulse and respiration rates decrease slightly

Growth rate is similar to that of previous year

Average weight of 16.7 kg (36.8 lbs)

Average height of 103 cm (40.5 inches)

Birth length has doubled

Maximum potential for development of amblyopia

Skips and hops on one foot

Catches ball reliably

Throws ball overhead

Walks down stairs using alternate footing

Uses scissors successfully to cut out picture following outline

Can lace shoes but may not be able to tie bow

In drawing, copies a square, traces a cross and diamond, adds three parts to stick figure

Has vocabulary of 1500 words or more

Uses sentences of four or five words

Questioning is at peak

Tells exaggerated stories

Knows simple songs

May be mildly profane if associates with older children

Obeys four prepositional phrases such as under, on top of, beside, in back of, or in front of

Names one or more colors

Comprehends analogies such as, “If ice is cold, fire is _______.”

Very independent

Tends to be selfish and impatient

Aggressive physically and verbally

Takes pride in accomplishments

Has mood swings

Shows off dramatically, enjoys entertaining others

Tells family tales to others with no restraint

Still has many fears

Play is associative

Imaginary playmates are common

Uses dramatic, imaginative, and imitative devices

Sexual exploration and curiosity demonstrated through play such as being “doctor” or “nurse” (see text)

Is in phase of intuitive thought

Causality is still related to proximity of events

Understands time better, especially in terms of sequence of daily events

Unable to conserve matter

Judges everything according to one dimension such as height, width, or order

Immediate perceptual clues dominate judgment

Is beginning to develop less egocentrism and more social awareness

May count correctly but has poor mathematic concept of numbers

Obeys because parents have set limits, not because of understanding of right or wrong

Rebels if parents expect too much such as impeccable table manners

Takes aggression and frustration out on parents or siblings

Do’s and don’ts become important

May have rivalry with older or younger siblings; may resent older sibling’s privileges and younger sibling’s invasion of privacy and possessions

May “run away” from home

Identifies strongly with parent of opposite sex

Is able to run simple errands outside the home

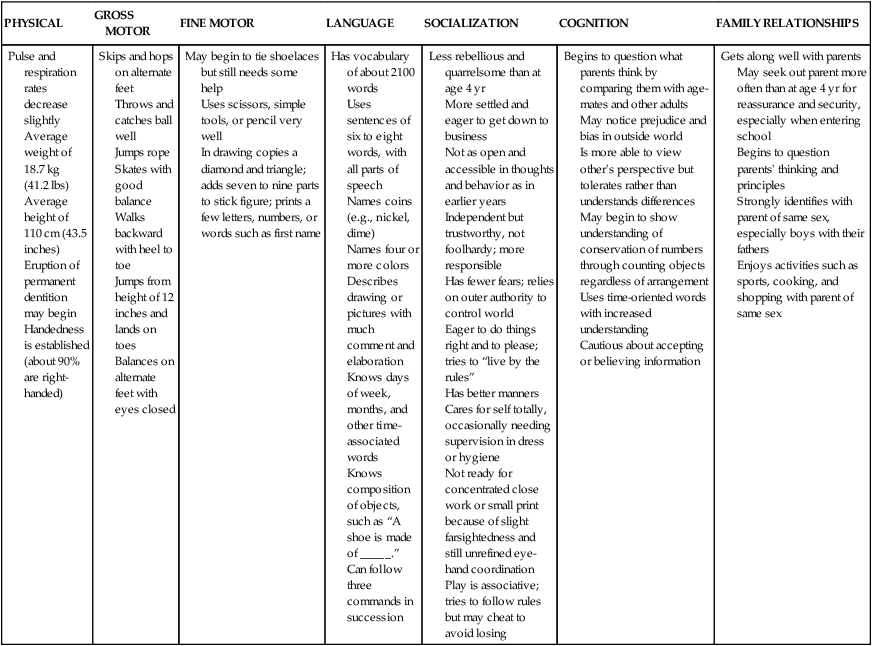

Age 5 Yr

Pulse and respiration rates decrease slightly

Average weight of 18.7 kg (41.2 lbs)

Average height of 110 cm (43.5 inches)

Eruption of permanent dentition may begin

Handedness is established (about 90% are right-handed)

Skips and hops on alternate feet

Throws and catches ball well

Jumps rope

Skates with good balance

Walks backward with heel to toe

Jumps from height of 12 inches and lands on toes

Balances on alternate feet with eyes closed

May begin to tie shoelaces but still needs some help

Uses scissors, simple tools, or pencil very well

In drawing copies a diamond and triangle; adds seven to nine parts to stick figure; prints a few letters, numbers, or words such as first name

Has vocabulary of about 2100 words

Uses sentences of six to eight words, with all parts of speech

Names coins (e.g., nickel, dime)

Names four or more colors

Describes drawing or pictures with much comment and elaboration

Knows days of week, months, and other time-associated words

Knows composition of objects, such as “A shoe is made of _____.”

Can follow three commands in succession

Less rebellious and quarrelsome than at age 4 yr

More settled and eager to get down to business

Not as open and accessible in thoughts and behavior as in earlier years

Independent but trustworthy, not foolhardy; more responsible

Has fewer fears; relies on outer authority to control world

Eager to do things right and to please; tries to “live by the rules”

Has better manners

Cares for self totally, occasionally needing supervision in dress or hygiene

Not ready for concentrated close work or small print because of slight farsightedness and still unrefined eye-hand coordination

Play is associative; tries to follow rules but may cheat to avoid losing

Begins to question what parents think by comparing them with age-mates and other adults

May notice prejudice and bias in outside world

Is more able to view other’s perspective but tolerates rather than understands differences

May begin to show understanding of conservation of numbers through counting objects regardless of arrangement

Uses time-oriented words with increased understanding

Cautious about accepting or believing information

Gets along well with parents

May seek out parent more often than at age 4 yr for reassurance and security, especially when entering school

Begins to question parents’ thinking and principles

Strongly identifies with parent of same sex, especially boys with their fathers

Enjoys activities such as sports, cooking, and shopping with parent of same sex

Coping with Concerns Related to Normal Growth and Development

Preschool and Kindergarten Experience

Sex Education

Stress

Aggression

Speech Problems

Promoting Optimal Health During the Preschool Years

Nutrition

Sleep and Activity

Sleep Problems

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Preschooler and Family

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access