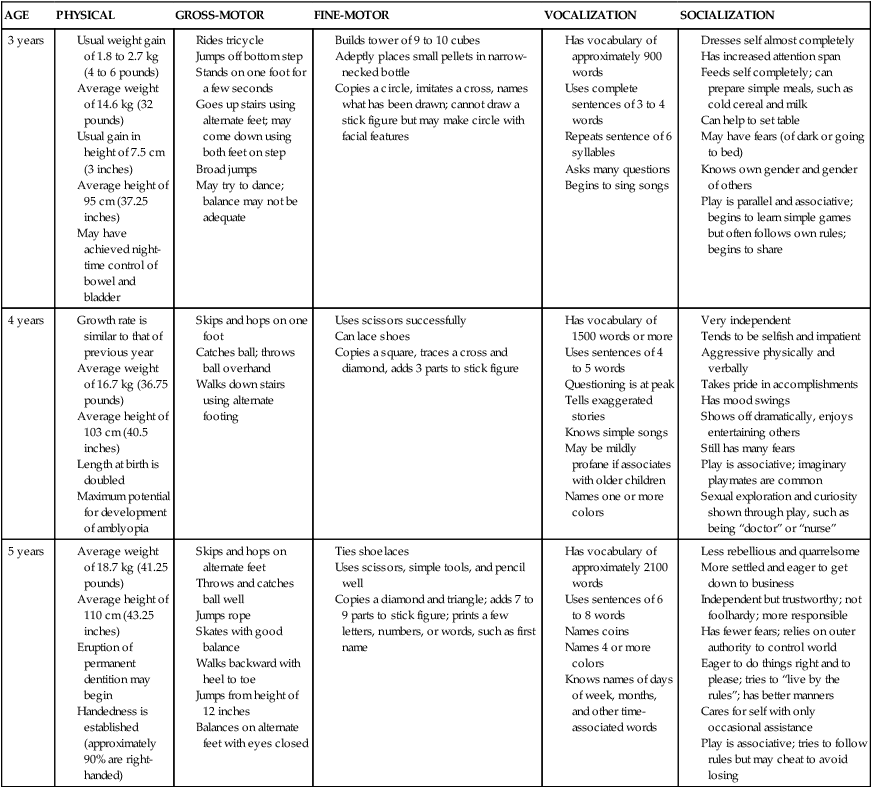

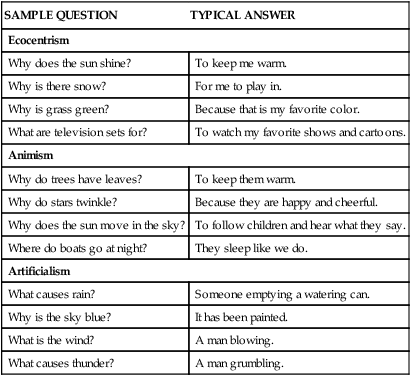

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Describe the physical and psychosocial development of children from 3 to 5 years of age, listing age-specific events and guidance when appropriate 3. Describe the characteristics of a good preschool facility 4. Discuss the value of play in the life of a child 5. Designate two toys suitable for the preschool child, and provide the rationale for each choice 6. Identify the developmental characteristics that predispose the preschool child to certain accidents, and suggest methods of prevention for each type of accident The child from 3 to 5 years of age is often referred to as the preschool child. This period is marked by a slowing down in the child’s growth. By 1 year, infants have tripled their birth weight, whereas by the age of 6 years, these same children have only doubled their 1-year weight. For instance, the boy who weighs 20 pounds on his first birthday will probably weigh about 40 pounds on his fifth. Weight gain during the preschool years is about 5 pounds per year. The child between 3 and 5 years of age grows taller and loses the chubbiness that is seen during the toddler period. Height increases approximately 2.5 to 3 inches per year. Appetite fluctuates widely. The normal pulse rate is 90 to 110 beats per minute. The respiration rate during relaxation is about 20 breaths per minute. The systolic blood pressure is about 92 to 95 mm Hg; the diastolic blood pressure is about 56 mm Hg. By the preschool years, at least 90% of brain growth is achieved and handedness begins to become apparent. A summary of preschooler growth and development is presented in Table 8-1. Table 8-1 Summary of Preschooler Growth and Development Modified from Hockenberry, M., and Wilson, D. (2007). Wong’s nursing care of infants and children (8th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. Another characteristic of this period is egocentrism, a type of thinking in which children have difficulty seeing any point of view other than their own. Children’s knowledge and understanding are restricted to their own limited experiences, and, as a result, misconceptions arise. One of these misconceptions is animism. This is a tendency to attribute life to inanimate objects. Another is artificialism, the idea that the world and everything in it is created by human beings (Table 8-2). Table 8-2 The Nature of Early Childhood Thought From Helms, D., and Turner, J. (1978). Exploring child behavior: basic principles (p. 447). Philadelphia: Saunders, with permission. Preschoolers enjoy dressing up and pretending to be real and make-believe characters (Figure 8-1). They love to imitate people around them and often mimic what they see their parents doing. Playing “store” or “office” or doing household chores such as “lawn mowing” or “doing the dishes” are activities that preschoolers enjoy. Toy companies manufacture many toys that encourage the preschooler to engage in this domestic mimicry. Children at this age are just beginning to learn right from wrong. Spiritual development is strongly linked to development of the conscience (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2007). The preschooler is just beginning to understand spiritual matters. Rudimentary knowledge is provided by parents or significant others. Their concrete thinking allows them to perceive God as an imaginary friend. Children this age enjoy hearing Bible stories and reciting simple prayers. If hospitalized, saying prayers as part of their routine can actually help with the stressors of hospitalization. Four-year-olds can use scissors successfully. They can lace their shoes and do simple buttons (Figure 8-2). Vocabulary has increased to about 1500 words. They run simple errands and can play with others for longer periods of time. Many feats are done for a purpose. For instance, they no longer run just for the sake of running. Instead, they run to get someplace or to see something. They are imaginative and like to pretend they are firefighters or cowboys. Much of their play time is spent pretending. They may even have an imaginary friend. The friend may “exist” until the child starts school. They also begin to prefer playing with friends of the same gender rather than with those of the opposite gender. The preschool child enjoys simple toys. They love to color pictures and have mastered the use of large crayons (Figure 8-3). Raw materials are more appealing than toys that are ready-made. An old cardboard box that can be moved about and climbed into is more fun than a dollhouse with tiny furniture. A box of sand or colored pebbles can be made into roads and mountains. A small mirror becomes a lake. “Dress up” becomes more dramatic, especially with the 4-year-old. Parents should avoid showering their children with ready-made toys. Instead they can select materials that are absorbing and that stimulate the child’s imagination. Usually young children realize that others die but do not relate this to themselves. If they continue to pursue the question of whether or not they will die, parents should be casual and reassure them that people do not generally die until they have lived a long and happy life. Of course, as they grow older, they will discover that sometimes children do die. The underlying idea, nevertheless, is to encourage questions as they appear and gradually help them accept the truth without undue fear. See Chapter 22 for further discussion on end-of-life issues.

The Preschool Child

General Characteristics and Development

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

Theories of Development

SAMPLE QUESTION

TYPICAL ANSWER

Ecocentrism

Why does the sun shine?

To keep me warm.

Why is there snow?

For me to play in.

Why is grass green?

Because that is my favorite color.

What are television sets for?

To watch my favorite shows and cartoons.

Animism

Why do trees have leaves?

To keep them warm.

Why do stars twinkle?

Because they are happy and cheerful.

Why does the sun move in the sky?

To follow children and hear what they say.

Where do boats go at night?

They sleep like we do.

Artificialism

What causes rain?

Someone emptying a watering can.

Why is the sky blue?

It has been painted.

What is the wind?

A man blowing.

What causes thunder?

A man grumbling.

Physical, Psychosocial, and Cognitive Development

The 3-Year-Old

The 4-Year-Old

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Preschool Child

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access