The Politics of the Pharmaceutical Industry

Doug Olsen

“There’s a better way to do it…find it.”

—Thomas Edison

Prescription medications have been a mainstay of modern medical therapy since the 1920s, starting with insulin for diabetes and followed by the development of vaccinations for prevention and antibiotics. This trend accelerated in the 1950s, with the development of drugs to treat chronic and incipient conditions, hypertension, heart disease, type II diabetes, psychiatric disorders, and cancer. Ten years ago, when physicians were surveyed about the most important innovations in medical treatment since 1976, 11 of the top 20 were medications (Fuchs & Sox, 2001). Today, 46.5% of Americans take at least one prescription drug (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2009), and 71% of all outpatient visits result in a prescription (Cherry et al., 2008).

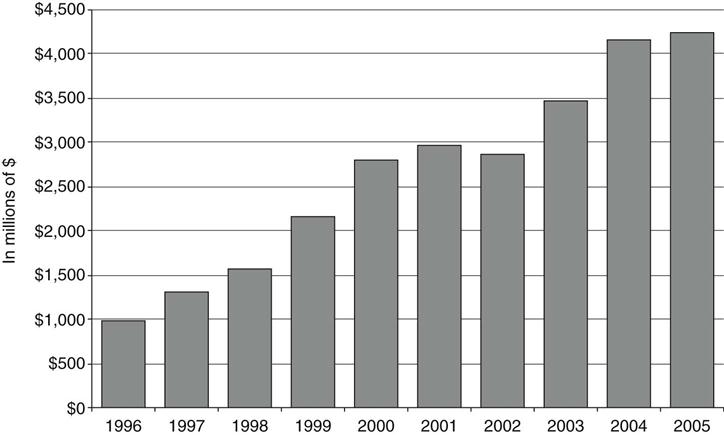

This demand fuels a large, profitable industry with $192 billion in sales and $36 billion in profits in 2002 (Fortune 500, 2003). Health care was 15.3% of the GDP in 2006, with 10% ($672 per person) of total health expenditures going for prescription drugs (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2008). There was a 171% increase in overall prescribing in the outpatient setting from 1995-1996 to 2004-2005, with the increase being over 500% for some types of drugs (Figure 90-1) (NCHS, 2009).

Demand combined with large sums of money in the pharmaceutical industry translates into political clout. According to Public Citizen’s Congress Watch in 2002, the industry spent $91.4 million in lobbying with 675 individual lobbyists. Also in 2002, the industry spent $17.6 million on advertising during the legislative process to create Medicare Part D.

The United States pharmaceutical industry emphasizes the money it spends on research and development. Estimated at $58.8 billion in 2007, it is the most visible figure in the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) 2008 Annual Report (2008a). However, critics claim that research funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and buyouts of drugs in-testing from small entrepreneurial efforts make up an increasing proportion of development funds, and that actual basic research by the large pharmaceuticals is shrinking (Angell, 2004). While the industry trumpets research and development funding, it combines marketing and administration costs, making it difficult to obtain reliable figures for marketing. The total marketing budget for the industry was estimated at $29.9 billion in 2005, up from $11.4 billion in 1997 (Donohue, Cevasco, & Rosenthal, 2007).

These numbers reveal an American industry driven by market forces to maximize return on investment. Some industry analysts express concern that overemphasis on “low-hanging fruit” in the form of me-too drugs (drugs with similar effects to available medications) and increasing market share by advertising have deemphasized basic research, resulting in less innovation (Public Citizen’s Congress Watch, 2002).

Values Conflict

The industry is designed to produce profits, and like the manufacture of most other commodities in the United States, the manufacture of medications is shaped by market forces. However, medications, essential to health care, are also held to be a public good. The dual private-enterprise/public-good nature of drug manufacturing helps explain some of the industry’s controversial aspects including industry-funded education and advertising campaigns aimed at clinicians and directly to patients. Reinhardt (2001) states, “On some occasions, lawmakers and the general public seem to expect pharmaceutical firms to behave as if they were community owned, nonprofit entities. At the same time, the firms’ owners … always expect the firms to use their market power and political muscle to maximize the owners’ wealth” (p. 137).

A free enterprise system that lacks the ability to patent new items discourages innovation because inventions that can be freely copied confer little economic inventive for developing novel products (Taylor, 2007). The industry puts the expense of bringing a new drug to market at $1.3 billion (PhRMA, 2008c). So, to offset development expenses and encourage innovation, new medications are patented with exclusive marketing rights for 7 years (PhRMA, 2008c). This creates an incentive to deliver new drugs to market, while striving for rapid clinical acceptance. Financial assessments of a pharmaceutical company always include the “pipeline” or the drugs in development. Companies are often on a boom-bust cycle, with profits soaring when a new drug emerges and falling when the pipeline dries up (Ekelund & Persson, 2003).

The ceaseless search for blockbuster drugs results in drug development focused on those classes of medication producing large profits. The three top sellers are antidepressants, drugs for acid reflux, and statins for cholesterol reduction. Drug development based on potential profit will differ from development based on dispassionate assessment of public need. The Orphan Drug Act of 1983, providing financial incentives to develop treatments for rare diseases, is an example of an attempt to mitigate the effect of the industry’s dual nature on development of new drugs.

Drug companies increase profits in two ways, bringing new medications to market and increasing the market for existing medications. Firms increase market share by advertising to prescribers and the public, as well as promotion activities that include sponsorship of clinical education and assistance to patient advocacy groups. One of the chief promotion methods to clinicians, called detailing, combines education-like activity with traditional advertising. In detailing, a company representative provides clinicians with educational materials, free samples, meals, and “reminder” items, including mugs, pens, or toys. In 2005, an estimated $6.8 billion dollars, or 22% of promotion spending, went to detailing. In addition, $18.4 billion, 58% of promotion spending, went to free drug samples (Donohue, Cevasco, & Rosenthal, 2007).

Direct to Consumer Marketing

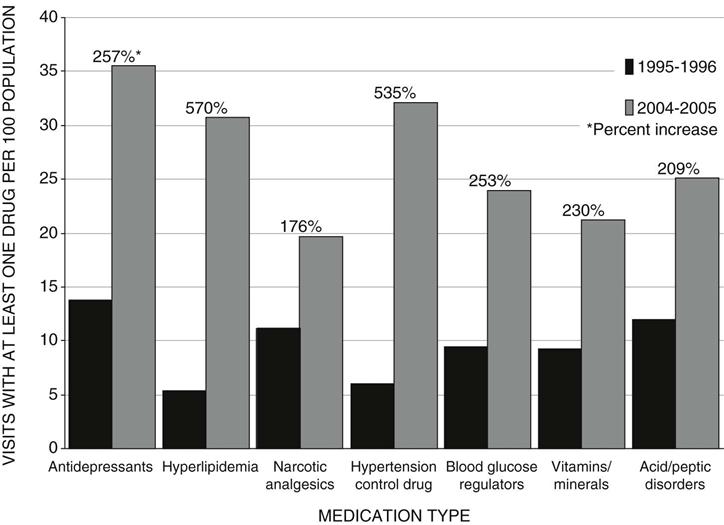

Direct to Consumer (DTC) advertising began in earnest in 1997, 6 months after David Kessler, who opposed easing regulations to allow more DTC, left his post as commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). At that time, it was made easier to comply with the regulatory requirement that DTC broadcast advertising contain a “major statement” of the drug’s risks, and “adequate provision” for consumers to obtain full information about the drug. These conditions are now satisfied with a risk statement and referral to concurrent print ads, websites, or toll-free telephone numbers (Bradford, Kleit, Nietert, & Ornstein, 2005). Industry spending on DTC advertising is estimated to have increased from $579 million in 1996 to $3.8 billion in 2004 (Bradford et al., 2005) (Figure 90-2). Profit spurred the growth of DTC marketing, and it is estimated that money spent on DTC advertising produces a fourfold return in sales (Rosenthal, Berndt, Donohue, Epstein, & Frank, 2003).

The heated debate about DTC advertising highlights the ambivalence over medications as both public good and lucrative product. Both sides in the debate frame arguments in terms of DTC’s effect on public health, passing over profitability as a rationale for favoring DTC advertising. Ethical and policy reasons favoring DTC advertising include increased public awareness of treatment options and enhanced ability for informed choices by consumers. One argument against DTC advertising is that the information disseminated by the ads is biased—designed to build profit and not simply a dispassionate account of risks, benefits, and alternatives essential to informed choice.

Research shows that while awareness is increased, the information received by the public through advertising is problematic. A series of FDA surveys (Aikin, Swasy, & Braman, 2004) indicates that the public and physicians view DTC advertising as raising awareness of treatment options and stimulating clinical discussion, but also note that the ads tend to overemphasize benefits. Woloshin, Schwartz, and Welch (2004) found that consumers, when given effectiveness data, perceived drugs as less beneficial than when given the qualitative data typical of most drug advertising. Wilkes, Bell, & Kravitz (2000) reported that 43% of consumers believed that only completely safe drugs could be advertised, and 21% believed that advertising was restricted to extremely effective drugs.

The industry largely confines advertising to a few classes of drugs that generate the greatest profit rather than focus on distributing information on the basis of public need (Donohue, Cevasco, & Rosenthal, 2007). The drug with the most DTC spending treats heartburn, and a sleep aid ranks second (Donohue, Cevasco, & Rosenthal, 2007). There are also indications that prescribing patterns are influenced in ways inconsistent with health priorities. Weissman and colleagues (2003) found that 25% of patients who asked clinicians about an advertised drug received a new diagnosis; erectile dysfunction was the most common new diagnosis.

Another concern about DTC marketing is disease mongering, that is, promoting exaggerated perceptions of the seriousness of known disorders or even inventing new diseases to open new markets and improve sales. Conditions offered as examples include female sexual dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, acid reflux, insomnia, and allergies (Applbaum, 2006).

Conflict of Interest

The large quantity of money spent promoting drugs to clinicians raises conflict-of-interest concerns that arise from the industry’s dual nature. The public wants treatment to be based solely on a clinical assessment of the patient’s best interests, not on personal or monetary considerations tied to specific medications, but industry promotion is designed to sell particular drugs in service of the company’s primary goal of profitability.

Education

Drug companies are a major sponsor of medical continuing education. Between 1998 and 2003, commercial sponsorship of continuing medical education went from $302 million to $971 million (Steinbrook, 2005). Industry marketing has become so integral to clinical education that PhRMA (2008c) claims, “Restricting pharmaceutical marketing would likely significantly reduce the dissemination of information about new treatments…” In a report in the New England Journal of Medicine, Steinbrook (2008) concluded, “Continuing medical education has become so heavily dependent on support from pharmaceutical and medical device companies that the medical profession may have lost control over its own continuing education.” In 2008, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) identified the conflict between medical treatment as a social good and medical treatment as a commodity. In their report “Industry Funding of Medical Education,” the AAMC states “these conflicts can have a corrosive effect on three core principles of medical professionalism: autonomy, objectivity, and altruism” (AAMC, 2008, p. 4).

Both the American Nurses Association through the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) and the American Medical Association (AMA) through the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) attempt to eliminate conflicts of interest with strict guidelines for commercial sponsorship of accredited continuing education. The guidelines emphasize independence of content, transparency through conflict of interest disclosures by content developers, separation of promotion from educational activity, and appropriate use of funds (ANCC, n.d.; ACCME, 2007). The AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs recommends that physicians, medical schools, and professional associations stop accepting industry funding of education, and the American Psychiatric Association announced its intention to phase out industry-funded education (Kuehn, 2009).

However, discerning when education is sponsored by a pharmaceutical manufacturer is difficult because the money is often passed through medical-education corporations or industry foundations. Other times the information is clearly from a drug company with little concern over any real or perceived conflict of interest. A downloadable 3-part CE series titled Counseling Points (n.d.), designed to resemble journal articles and distributed by the American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA) in 2009, provides clinical information clearly marked with drug-company sponsorship, without claim of authorship. When I asked about the appearance of bias created by the lack of scholarly attribution in a commercially sponsored product, the APNA expressed no concern. We do not know how much commercial money is directed for nursing education, but it appears to be increasing as more nurses prescribe medications.

Industry-sponsored education is a form of marketing. Drugs are so integral to modern health care that comprehensive education in almost all areas involves extensive discussion of medications, and even unbiased appraisals may favor one drug over another. But when commercial interests sponsor education, it cannot be discerned where unbiased evaluation ends and promotion begins. For example, if two experts have an honest disagreement about treatments, and the company sponsors the one that holds their drug superior to the lifestyle change favored by the other expert, then the discourse is biased by giving one side resources to magnify their opinion. Social justice is achieved through fair and equal access to all forms of discourse (Horster, 1992). Distortion of the discourse on health care in the public and professional community occurs through marketing techniques applied to products with the potential to generate revenue. And so, in market-driven public discourse, health practices with modest or little profit potential, such as exercise and moderate eating, are unlikely to receive the attention accorded to highly profitable pharmaceuticals.

Gifts

The giving of explicit or disguised gifts also creates potential conflicts of interest in clinicians. After years of anecdotal denial by clinicians that gifts carry influence, data suggest that physicians’ prescribing practices are influenced by drug company gifts (Sierles et al., 2005; Chew et al., 2000). So, voluntary guidance from the industry (PhRMA, 2008b), the government (Office of Inspector General, 2003), and the AMA (2005) limits the practice of giving gifts. PhRMA guidelines prohibit both the most egregious types of gifts given in the past by drug companies (including cash kickbacks, event tickets, and “fees” for bogus consultations) as well as those once considered benign, including mugs or pens. Voluntary PhRMA guidelines suggest gifts be limited to educational or clinically useful items of less than $100. Provision of meals is still allowed at clinical sites when in conjunction with educational presentations.

While the AMA has issued ethical guidance for physicians, guidance for nurses is notably absent. Major U.S. nursing organizations say little about relations with the pharmaceutical industry. The ANA has issued no guidance specific to relations with industry. Despite calls for ethical guidance on this topic for nurse practitioners (Crigger, 2005), the American College of Nurse Practitioners (ACNP) has only two related items on their website: (1) a position paper calling for DTC marketing to include referrals “to all qualified health care professionals” and not just physicians, and (2) a presentation provided by PhRMA reviewing its guidelines for clinician relations that are blatantly self-promoting (e.g., “Pharmaceutical company representatives help speed the dissemination of valuable improvements in medical care…”) (Brigner, 2009). The American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (n.d.) website has a “Petition to End the Use of Physician-Biased Language in DTC Advertising” but no guidance on the ethics of relations with industry.

Nurses represent a relatively untapped and naïve resource for pharmaceutical marketing (Jutel & Menkes, 2008). Although only some nurses prescribe, nurses influence the use and purchase of drugs in other ways, including suggesting the use of particular medications, distributing medications, reporting adverse effects, conducting research, as well as managing many clinical trials. In a survey of more than 500 nurse practitioners, Blunt (2005) reported that 80% altered their prescribing practice after a drug company interaction.

Samples

Providing free samples of drugs is another controversial form of gifts given to clinicians. The claim is often made that prescribers use these to benefit the economically disadvantaged. However, research shows that recipients of sample medications are more likely the wealthy rather than the poor or uninsured (Cutrona et al., 2008). The free samples are usually of new, expensive drugs that the patient may not be able to afford after the samples run out.

Summary

The most pervasive effect of having a market-driven industry expected to deliver a public good may be the subtle shift in the nature of the public benefit expected. The sum effect of the vast amount of money spent to promote drug sales through education and advertising to clinicians and advertising directly to the public may be to alter the public’s concept of life and health to conform with the interests of the pharmaceutical industry. This means a worldview where life’s problems are medical conditions visited on us through no fault of our own and whose solutions require external interventions—most often a pill. In this view, personal responsibility means recognizing and admitting to having a disorder and then being compliant with treatment.

Medications are a miracle of modern health care. But the tradition will continue only if unbiased information on their benefits and uses is distributed in accordance with rational decisions about the public’s health, rather than the effect on industry profits.

For a list of related websites, please refer to your Evolve Resources at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Mason/policypolitics/

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree