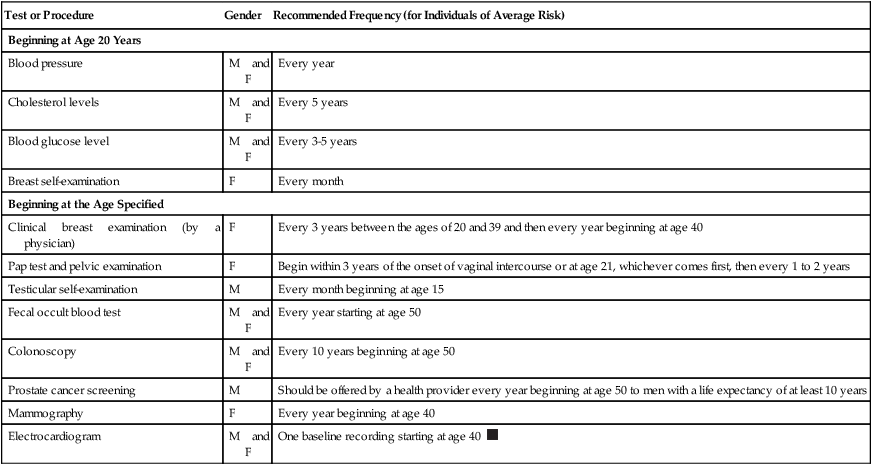

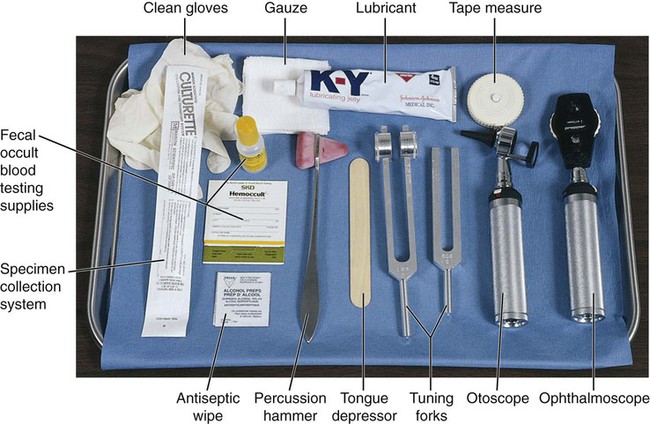

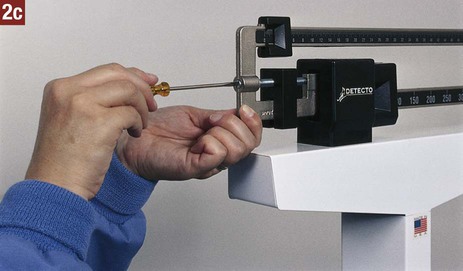

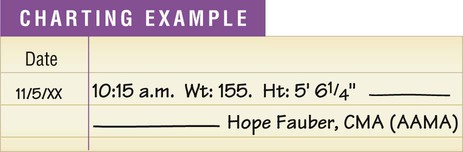

Final diagnosis. Often simply called the diagnosis, this term refers to the scientific method of determining and identifying a patient’s condition through evaluation of the health history, the physical examination, laboratory tests, and diagnostic procedures. A final diagnosis is crucial because it provides a logical basis for treatment and prognosis. Clinical diagnosis. The clinical diagnosis is an intermediate step in the determination of a final diagnosis. The clinical diagnosis of a patient’s condition is obtained through evaluation of the health history and the physical examination without the benefit of laboratory or diagnostic tests. Laboratory and diagnostic imaging facilities provide a space to specify the clinical diagnosis on their request forms; this information assists the facility in correlating data from their test results with the physician’s needs. When the physician has analyzed the test results, a final diagnosis can often be established. Differential diagnosis. Two or more diseases may have similar symptoms. The differential diagnosis involves determining which of these diseases is producing the patient’s symptoms so that a final diagnosis can be established. For example, streptococcal sore throat and pharyngitis have similar symptoms. A differential diagnosis is made by obtaining a throat specimen and performing a strep test. Prognosis. The prognosis consists of the probable course and outcome of a patient’s condition and the patient’s prospects for recovery. Risk factor. A risk factor is a physical or behavioral condition that increases the probability that an individual will develop a particular condition; examples are genetic factors, habits, environmental conditions, and physiologic conditions. The presence of a risk factor for a certain disease does not mean that the disease will develop; it means only that a person’s chances of developing that disease are greater than those of a person without the risk factor. For example, cigarette smoking is a risk factor for developing lung cancer and heart disease. A person who smokes has a higher risk of developing lung cancer than a person who does not or who has stopped smoking. Acute illness. An acute illness is characterized by symptoms that have a rapid onset, are usually severe and intense, and subside after a relatively short time. In some cases, the acute episode progresses into a chronic illness. Examples of acute illness include colds, influenza, strep throat, and pneumonia. Chronic illness. A chronic illness is characterized by symptoms that persist for longer than 3 months and show little change over a long time. Examples of chronic illness include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and emphysema. Therapeutic procedure. A therapeutic procedure is performed to treat a patient’s condition with the goal of eliminating it or promoting as much recovery as possible. Examples of therapeutic procedures include administration of medication, ear and eye irrigations, and application of heat and cold. Laboratory testing. Laboratory testing involves the analysis and study of specimens obtained from patients to assist in diagnosing and treating disease. Examples of laboratory testing include the hemoglobin test, glucose test, urinalysis, and strep testing. Diagnostic procedure. A diagnostic procedure is a procedure performed to assist in the diagnosis of a patient’s condition; examples include electrocardiography, colonoscopy, and mammography. 1. Ensure that the examining room is free of clutter and well lit. 2. Check the examining rooms daily to ensure there are ample supplies. Restock supplies that are getting low. 3. Empty waste receptacles frequently. 4. Replace biohazard containers as necessary. When removing biohazard containers from the examining room (see Chapter 17), follow the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. 5. Make sure the room is well ventilated, and install an air freshener to eliminate odors. 6. Maintain room temperatures that are comfortable not only for a fully clothed individual, but also for an individual who has disrobed. 7. Clean and disinfect examining tables, countertops, and faucets daily. 8. Remove dust and dirt from furniture and towel dispensers. 9. Change the examining table paper after each patient by unrolling a fresh length. Check to ensure there is an ample supply of gowns and drapes ready for use. 10. Ensure that the examining room door is closed during the examination because patient privacy is paramount. 11. Properly clean and prepare equipment, instruments, and supplies that are used for patient examinations so that they are ready for use by the physician. Table 20-1 lists the equipment and supplies, along with their uses, that may be employed during a physical examination. Table 20-1 Equipment and Supplies for the Physical Examination From Bonewit-West K: Clinical procedures for medical assistants, ed 8, St Louis, 2011, Saunders. 12. Check equipment and instruments regularly to verify that they are in proper working condition. This protects the patient from harm caused by faulty equipment. 13. Have equipment and supplies ready for the examination and arranged for easy access by the physician. Equipment and supplies needed for the physical examination vary according to the type of examination and the physician’s preference (Figure 20-1). 14. Know how to operate and care for each piece of equipment and each instrument. The manufacturer provides an operating manual, which should be read carefully and thoroughly and kept available for reference. The medical assistant routinely measures the weight and height of many types of patients. The process of measuring the patient is mensuration. A change in weight may be significant in the diagnosis of a patient’s condition and in prescribing the course of treatment. Underweight and overweight patients who follow a diet therapy program should be weighed at regular intervals to determine their progress. Prenatal patients are weighed during each prenatal visit to assist in the assessment of fetal development and of the mother’s health. Procedure 20-1 describes how to measure height and weight.

The Physical Examination

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

PROCEDURES

Preparation for the Physical Examination

Measuring Weight and Height

Body Mechanics

Positioning and Draping

Wheelchair Transfer

Assessment of the Patient

Assisting the Physician

Introduction to the Physical Examination

Definitions of Terms

Preparation of the Examining Room

Item

Description and Purpose

Patient examination gown

Gown made of disposable paper or cloth that provides patient modesty, comfort, and warmth.

Drape

A length of disposable paper or cloth to cover a patient or parts of a patient to provide comfort and warmth and reduce exposure.

Sphygmomanometer

Instrument used to measure blood pressure.

Stethoscope

Instrument used to auscultate body sounds, such as blood pressure and lung and bowel sounds.

Thermometer

Instrument used to measure body temperature.

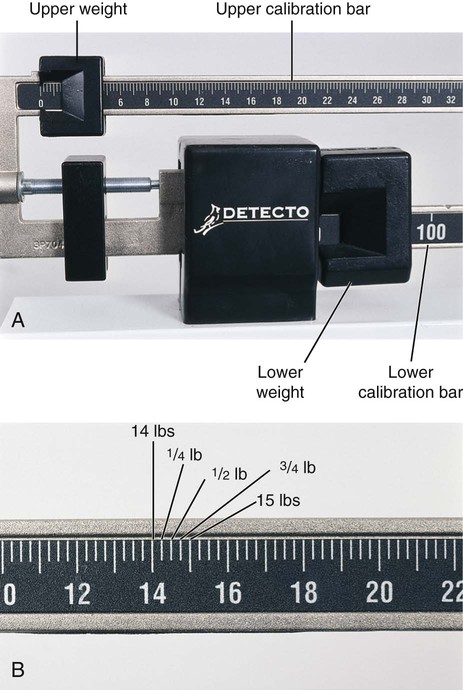

Upright balance scale

Device used to measure weight and height.

Otoscope

Lighted instrument with lens, used to examine external ear canal and tympanic membrane.

Tuning fork

Small metal instrument consisting of stem and two prongs, used to test hearing acuity.

Ophthalmoscope

Lighted instrument with lens, used for examining interior of eye.

Tongue depressor

Flat wooden blade used to depress patient’s tongue during examination of mouth and pharynx.

Antiseptic wipe

Disposable pad saturated with antiseptic, such as alcohol, that is used to cleanse skin.

Tape measure

Flexible device calibrated in inches on one side and centimeters on the other side, used to measure patient (e.g., diameter of limb, head circumference).

Percussion hammer

Instrument with rubber head, used for testing neurologic reflexes.

Speculum

Instrument for opening body orifice or cavity for viewing (e.g., ear speculum, nasal speculum, vaginal speculum).

Disposable gloves

Gloves, usually latex, that are worn only once to provide protection from bloodborne pathogens and other potentially infectious materials.

Lubricant

Agent that is applied to physician’s gloved hand or to speculum that reduces friction between parts to make insertion easier.

Specimen container

Container in which body specimen is placed for transport to laboratory (after it has been labeled).

Tissues

Used for wiping body secretions.

Cotton-tipped applicator

Small piece of cotton wrapped around the end of a slender wooden stick, used for collection of specimen from the body.

Overhead examination light

Light mounted on flexible movable stand to focus light on area for good visibility.

Basin

Container in which used instruments are deposited.

Biohazard container

Specially made container used for receiving items that contain infectious waste.

Waste receptacle

Container for used disposable articles that do not contain infectious waste.

Measuring Weight and Height

The Physical Examination

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access