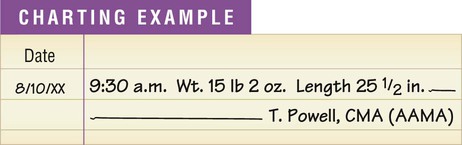

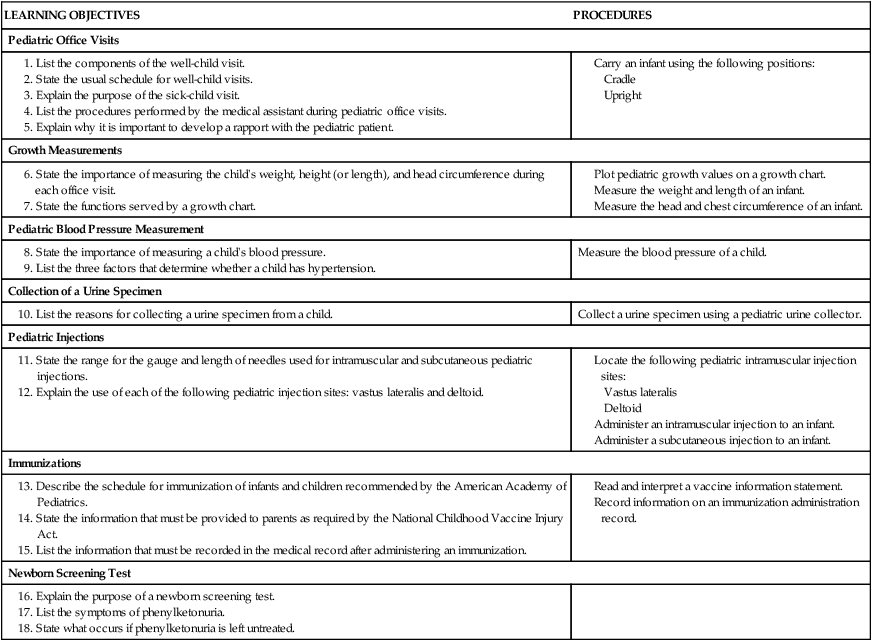

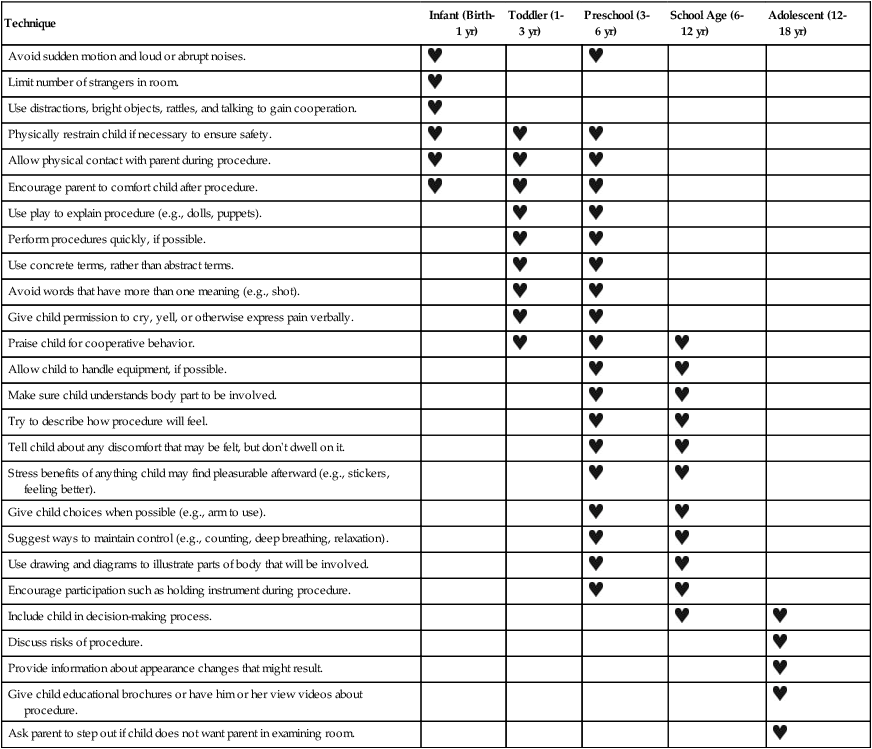

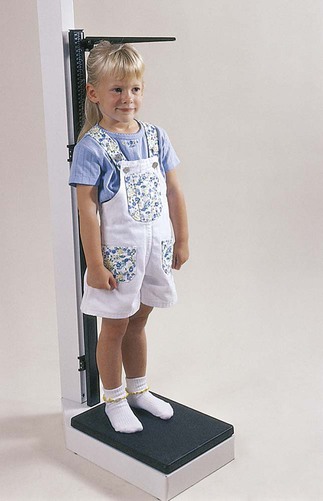

1. List the components of the well-child visit. 2. State the usual schedule for well-child visits. 3. Explain the purpose of the sick-child visit. 4. List the procedures performed by the medical assistant during pediatric office visits. 5. Explain why it is important to develop a rapport with the pediatric patient. 13. Describe the schedule for immunization of infants and children recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. 14. State the information that must be provided to parents as required by the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act. 15. List the information that must be recorded in the medical record after administering an immunization. There are two broad categories of pediatric patient office visits. The first is the well-child visit (also termed health maintenance visit), in which the physician progressively evaluates the growth and development of the child. A physical examination is performed during each well-child visit and is directed toward discovering any abnormal conditions commonly associated with the stage of development reached by the child. Table 24-1 provides an outline of normal development during infancy. The child also receives necessary immunizations during these visits. Table 24-1 Milestones of Gross and Fine Motor Development in Infancy From Leahy JM, Kizilay PE: Foundations of nursing practice, Philadelphia, 1998, Saunders. The medical assistant must establish a rapport with the pediatric patient. If the medical assistant gains the child’s trust and confidence, the child is likely to cooperate during an examination or procedure. Interacting with children requires special techniques. The techniques employed depend on the age of the child. Toddlers and preschool children often respond well to making a game of the procedure. Explaining the purpose of an instrument (e.g., the stethoscope) to a school-age child and allowing him or her to hold the instrument or even to help during the procedure may overcome fears in that age group (Figure 24-1). The medical assistant should always explain the procedure to children who are able to understand. Each child must be approached at his or her level of understanding. To do this, the medical assistant should know what to expect from a child at a particular age, in terms of motor and social development. Each child has his or her own individual rate of development; the descriptions of normal development based on age are meant to serve as a guide only and may have to be modified to meet individual needs. In addition, it is normal for an ill child to regress to an earlier level of behavior. Table 24-2 outlines techniques that can be used with various age groups to gain their cooperation during an examination or procedure. Table 24-2 Techniques for Interaction with Children From Bonewit-West K: Clinical procedures for medical assistants, ed 8, St Louis, 2011, Saunders. The medical assistant slides the left hand and arm under the infant’s back and grasps the infant’s arm from behind. The thumb and fingers should encircle the infant’s forearm. The infant’s head, shoulders, and back are supported by the medical assistant’s arm. Next, the medical assistant slips the right arm up and under the infant’s buttocks. The infant is cradled in the arm with his or her body resting against the medical assistant’s chest (Figure 24-2). The medical assistant slips the right hand under the infant’s head and shoulders. The fingers should be spread apart to support the infant’s head and neck. The left forearm is slipped under the infant’s buttocks to help support the infant’s weight. The infant should be allowed to rest against the medical assistant’s chest with the cheek resting on the medical assistant’s shoulder (Figure 24-3). A child’s weight is often used to determine nutritional needs and the proper dosage of a medication to administer to the child. The medical assistant should exercise care in measuring weight. Infants are weighed in a recumbent position, as outlined in Procedure 24-1. Older children are weighed in a standing position, as presented in Chapter 20. Another measure of a child’s growth is length, or height (stature). Length is measured in children younger than 24 months. The recumbent length is a measurement from the vertex of the head to the heel of the infant in a supine position, as outlined in Procedure 24-1. Two people are often needed to determine the length of an infant accurately. The parent’s help can be requested; the medical assistant must provide the parent with thorough instructions on what is to be done. Older children have their height measured in a standing position (Figure 24-4), as presented in Chapter 20.

The Pediatric Examination

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

PROCEDURES

Pediatric Office Visits

Growth Measurements

Pediatric Blood Pressure Measurement

Measure the blood pressure of a child.

Collection of a Urine Specimen

Collect a urine specimen using a pediatric urine collector.

Pediatric Injections

Immunizations

Newborn Screening Test

Pediatric Office Visits

Average Age (mo)

Gross Motor

Fine Motor

1

Turns head from side to side

Grasping reflex present

2

Holds head at 45-degree angle when prone

Holds rattle briefly

3

Begins rolling over

Grasps rattle or dangling objects

4

Slight head lag when pulled to sitting position

Brings objects to mouth

5

No head wobble when held in sitting position

Transfers objects from hand to hand

6

Sits without support

Manipulates and examines large objects with hands

7

Stands while holding on

Reaches for, grabs, and retains object

8

Pulls self to stand

Grasps objects with thumb and finger

9

Crawls backward

Begins to show hand preference

10

Creeps on hands and knees

Hits cup with spoon

11

Walks using furniture for support

Picks up small objects with thumb and forefinger (pincer grasp)

12

Stands alone easily

Puts three or more objects into container

12-16

Walks alone easily

Turns two or three pages in large cardboard book

Developing A Rapport

Technique

Infant (Birth-1 yr)

Toddler (1-3 yr)

Preschool (3-6 yr)

School Age (6-12 yr)

Adolescent (12-18 yr)

Avoid sudden motion and loud or abrupt noises.

Limit number of strangers in room.

Use distractions, bright objects, rattles, and talking to gain cooperation.

Physically restrain child if necessary to ensure safety.

Allow physical contact with parent during procedure.

Encourage parent to comfort child after procedure.

Use play to explain procedure (e.g., dolls, puppets).

Perform procedures quickly, if possible.

Use concrete terms, rather than abstract terms.

Avoid words that have more than one meaning (e.g., shot).

Give child permission to cry, yell, or otherwise express pain verbally.

Praise child for cooperative behavior.

Allow child to handle equipment, if possible.

Make sure child understands body part to be involved.

Try to describe how procedure will feel.

Tell child about any discomfort that may be felt, but don’t dwell on it.

Stress benefits of anything child may find pleasurable afterward (e.g., stickers, feeling better).

Give child choices when possible (e.g., arm to use).

Suggest ways to maintain control (e.g., counting, deep breathing, relaxation).

Use drawing and diagrams to illustrate parts of body that will be involved.

Encourage participation such as holding instrument during procedure.

Include child in decision-making process.

Discuss risks of procedure.

Provide information about appearance changes that might result.

Give child educational brochures or have him or her view videos about procedure.

Ask parent to step out if child does not want parent in examining room.

Carrying the Infant

Cradle Position

Upright Position

Growth Measurements

Weight

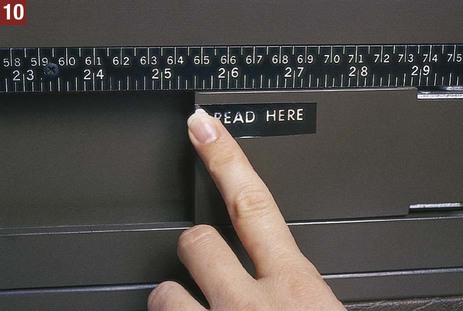

Length and Height

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Pediatric Examination

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

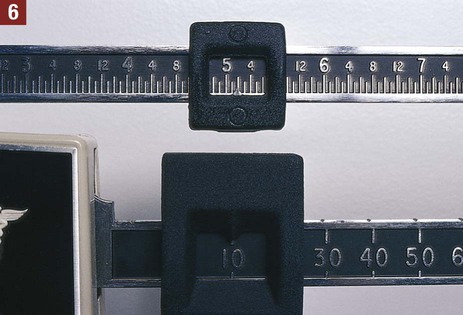

inch) from the measure. Jot down this value or make a mental note of it. (N

inch) from the measure. Jot down this value or make a mental note of it. (N inches.)

inches.)