Chapter 1 The Nurse Psychotherapist and a Framework for Practice

This chapter begins with the historical context of the nurse’s role as psychotherapist and the resources and challenges inherent in nursing in the development of requisite psychotherapy skills. A holistic model for psychiatric nursing practice is described. Using a holistic paradigm, elements of psychotherapy, caring, connection, narrative, complexity, and management of anxiety, are identified. Attention is then turned to the development of a framework for practice, beginning with a discussion of mental health and illness viewed through a cultural lens. The significant role of trauma in the development of, contribution to, and maintenance of mental health problems and psychiatric disorders is highlighted. A hierarchy of treatment aims is introduced on which to base interventions using a stage model for psychotherapy. This framework is based on neurophysiology and research that supports the premise that many mental health problems and psychiatric disorders involve a disturbance or dysregulation in the integration and connection of neural networks.

Who Does Psychotherapy?

The various disciplines licensed to conduct psychotherapy, depending on their respective state licensing boards, include psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, marriage and family therapists, counselors, and advanced practice psychiatric nurses (APPNs) (Table 1-1). Educational preparation, orientation, and practice settings vary greatly between and within each discipline. In addition to basic educational requirements unique for that discipline, there are many postgraduate psychotherapy training programs that licensed mental health practitioners may pursue, such as psychoanalytic, family therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), cognitive behavioral, hypnosis, and others. Each of these training programs offers certification and requires some length of training: approximately 1 year for EMDR (i.e., 20 academic didactic and 20 supervised hours, 10 additional consultative hours, 12 continuing educational units, 2 years’ experience with a license in mental health practice, and a minimum of 50 sessions with 25 patients) and 4 to 5 years for psychoanalytic training (i.e., 4 years of coursework and supervision, ongoing practica, and one’s own experience in psychoanalysis). Postgraduate training and ongoing supervision are encouraged for APPNs who wish to gain proficiency and deepen their knowledge in a particular modality of psychotherapy. Because it is highly unlikely that any one method will work for all problems of all people, the APPN who has additional skills such as hypnosis, EMDR, family therapy, imagery, or ego state work will be more likely to help those who seek help. There are many different ways to help the multitude of problems that patients have, and beware of therapists who believe that “one size fits all” and that psychotherapy orientation is a belief system. In other words, if the only tool you have is a hammer, you are likely to treat every problem you encounter as a nail.

Table 1-1 Basic Education, Orientation, and Setting of Psychotherapy Practitioners

| Discipline | Education | Orientation or Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrist | MD (Doctor of Medicine) or DO (Doctor of Osteopathy); 3-year psychiatric residency after medical school | Biologic treatment, acute care, psychopharmacology, and specific psychotherapy competencies for psychiatric MD residents; often inpatient orientation |

| Psychologist | PhD (Doctor of Philosophy, research doctorate in psychology) or PsyD (Doctor of Psychology, clinical doctorate in psychology); both usually 1-year internship after the doctorate | Psychotherapy and psychological testing |

| Masters-level psychologist | MA (Master of Arts) or MS (Master of Science) or MEd (Master of Education) | Psychotherapy: some modalities, psychological testing |

| Social worker | MSW (Master of Social Work) | Psychotherapy: interpersonal, family, group; community orientation |

| Marriage and family therapists | MA (Master of Arts) | Systems and family therapy, marriage counseling; community outpatient orientation |

| Counselor | MA (Master of Arts in counseling) or MEd (Master of Education in counseling) | Counseling, vocational and educational testing; outpatient orientation |

| Psychiatric-mental health advanced practice registered nurse (clinical nurse specialist in psychiatric-mental health nursing [PMHCNS] or psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioner [PMHNP]) | MSN/MS (Master of Science in Nursing) DNP (Doctor of Nursing Practice) (other research doctorates in nursing such as DNSc, DNS, DSN, or PhD do not prepare the nurse to practice psychotherapy, take advanced practice psychiatric certification examinations, or qualify to apply for state licensure as an advanced practice registered nurse [APRN]) | Psychopharmacology and psychotherapy: group, individual, and sometimes family; clinical research |

In 2002, the American Psychiatric Review Committee mandated that all psychiatric residency programs require competency training in psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, supportive, and brief psychotherapies and in psychotherapy combined with psychopharmacology in order to pass accreditation (Gabbard, 2004). Delineation of these competencies is important in that it is a direct response to the increasing emphasis on medication as the treatment for psychiatric disorders and reaffirms the importance of psychotherapy in psychiatric treatment. These core competencies in medical education indicate a significant cultural shift that also may herald academic changes for advanced practice psychiatric nursing education.

Many challenges in graduate nursing programs mitigate against APPNs attaining competency in psychotherapy. One challenge for nursing education is how to teach the requisite competencies and the essentials that are required of graduate nursing curricula without increasing the total credit load. To remain competitive, programs need to offer coursework that can be completed in a reasonable amount of time and with a reasonable number of credits. It is not possible in a short period—usually 2 years for most graduate nursing programs—to attain proficiency in psychotherapy, but competency must be achieved. Psychotherapy competency has been identified as necessary for all psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioner (PMHNP) programs as of 2003 (The National Panel, 2003). With the competencies delineated and the endorsement of them by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE) for accreditation, all graduate APPN programs seeking CCNE accreditation must teach these skills. These programs include the psychiatric-mental health clinical nurse specialist (PMHCNS) programs and those for the PMHNP. Official documents refer to both groups as psychiatric-mental health advanced practice registered nurses (PMHAPRNs), but for ease of reading, this textbook refers to both groups as APPNs.

Another change in nursing education that will significantly impact APPNs is the endorsement of the Doctorate of Nursing Practice (DNP) by leaders in nursing, the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculty (NONPF) and the American Association of the College of Nursing (AACN). This new degree is envisioned as a terminal practice degree and is proposed to supplant the Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) degree for nurse practitioners by 2015 and will include a clinical research focus. Impetus for this shift came from the lack of parity with other health care disciplines, the high amount of credits required in current masters’ curricula, current and projected shortage of faculty, and the increasing complexity of the health care system (Dracup et al., 2005). Debate continues about whether this terminal practice doctorate will enhance or dilute advanced practice. There are more than 200 programs in the planning stages, with some that have come to fruition, but there is no standardized curriculum. It is not clear how curricula and program requirements will continue to evolve to provide the needed practice expertise for APPN students. Faculty need current expertise in psychiatric advanced practice to effectively teach, and concerns have been expressed about whether graduate faculty have greater academic experience than practice experience because academia traditionally rewards faculty who publish and do research. Clinical practice and teaching are often overlooked in promotion decisions, and faculty members tend to emphasize research over practice, which may not bode well for APPN faculty expertise in psychotherapy skills.

A national survey of 120 academic psychiatric-mental health nursing graduate programs confirmed the scarcity of sites and found a wide range of individual psychotherapy practica hours required for students, ranging from a minimum of 50 to a maximum 440 hours in the programs for which a certain number of requisite hours are required for psychotherapy (Wheeler & Delaney, 2005). For approximately 50% of programs, however, no designated number of psychotherapy practice hours was required, and medication management hours were integrated along with psychotherapy. Consequently, most graduate psychiatric nurses leave graduate studies with a less than adequate knowledge base in this area, and they may not feel competent to practice psychotherapy. Faculty teaching students in graduate programs, when asked if their students had achieved competency on graduation, felt decidedly mixed. Two of 29 reported no, 15 reported yes, but the others were not so sure, with answers such as “very novice,” “for the most part, competency is a stretch,” “know they have to pursue more training after they finish the program,” “about 60% do,” “very beginning competency,” “yes for individual, not for family or group,” “clinical experiences limited in our area,” “most of the time,” “we encourage further training,” “encourage continued supervision and therapy,” and “don’t envision a future role as a psychotherapist” (Wheeler & Delaney, 2005).

Stages of Learning

Benner’s model (1984) of the role acquisition from novice to expert offers a model to examine the levels of competency for the novice nurse psychotherapist. It is likely that the graduate student who is pursuing a master’s degree or postmaster’s certificate as an APPN has practiced as an expert in an area of specialization before graduate studies. To transition from expert back to novice is often a painful and anxiety-provoking process. The beginning nurse psychotherapist has most likely interacted professionally with many different types of patients, but there is usually much anxiety about the first session with the patient in the role as psychotherapist. There is usually no one right thing to say. In psychotherapy, there is much ambiguity and often no right answers.

Juxtaposed to Benner’s model is the Four Stages of Learning Model, which may help to allay anxiety for those who are beginning to learn psychotherapy (Table 1-2). Although there is some controversy regarding who developed this model, it is thought that learning takes place in four stages:

1. Unconscious incompetence (i.e., we do not know what we do not know)

2. Conscious incompetence (i.e., we feel uncomfortable about what we do not know)

3. Conscious competence (i.e., we begin to acquire the skill and concentrate on what we are doing)

4. Unconscious competence (i.e., we blend the skills together, and they become habits, allowing use without struggling with the components)

Table 1-2 Comparison of the Stages of Learning and Benner’s Model

| Stages of Learning | Benner’s Model |

|---|---|

| Unconscious incompetency | Novice |

| Conscious incompetency | Advanced beginner |

| Conscious competency | Competency, proficiency |

| Unconscious competency | Expert |

Unique Qualities of Nurse Psychotherapists

The history of the one-to-one nurse-patient relationship and nurses conducting psychotherapy is detailed by Lego (1999) and Beeber (1995). Table 1-3 highlights the important events. The late 1940s were marked by the development of eight programs for the advanced preparation of nurses who cared for psychiatric patients. An extremely important debate took place over the next few decades about the nurse’s role as psychotherapist. This culminated in the 1967 American Nurses’ Association Position Paper on Psychiatric Nursing, which clarified the role of the clinical specialist in psychiatric nursing as psychotherapist, and certification for the specialty began in 1979. In the 1990s, PMHNP programs were developed, and this culminated in the PMHNP competencies that included psychotherapy as an essential competency required for all PMHNPs (Wheeler & Haber, 2004). The APPN role of psychotherapist has solid historical roots from the inception of advanced practice psychiatric-mental health nursing, whereas the prescribing role is a much more recent step in the evolution of the discipline (Bailey, 1999).

Table 1-3 Timeline of History of the Nurse Psychotherapist

| 1947 | Eight programs were established for advanced preparation of nurses to care for psychiatric patients. |

| 1952 | Hildegard Peplau establishes the first masters program in clinical nursing and a Sullivanian framework for practice of psychotherapy with inpatients and outpatients. |

| 1963 | Perspectives in psychiatric care were first published as a forum for articles on the nurse-patient relationship. |

| 1967 | ANA position paper supports the PMHCNS role of the individual, group, family, and milieu therapist. |

| 1979 | ANA certification granted for PMHCNS. |

| 2003 | ANCC certification granted for PMHNP. |

| 2004 | PMHNP competencies delineate individual, group, and family psychotherapy for practice. |

ANA, American Nurses’ Association; PMHCNS, psychiatric-mental health clinical nurse specialist; PMHNP, psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioner.

After the issue of whether nurses should do psychotherapy was resolved, the literature examined the unique qualities that nurses might possess as psychotherapists compared with those in other disciplines who practice psychotherapy. Several strengths were cited: nurses’ ability to be patient because they have worked with the chronically ill and have respect for others limitations, are realistic, and possess excellent observational skills, resourcefulness, innovation, and creativity (Smoyak, 1990); nurses view of the patient in a holistic way, crisis orientation, and a knowledge of general health concerns (Lego, 1973); and familiarity of daily life and experience of the hospitalized patients (Balsam & Balsam, 1974). Nurses usually have had a breadth of life experience and exposure to many different ages, ethnicities, occupations, socioeconomic status, cultures, and personalities. The novice nurse psychotherapist is well served through experience with communicating and connecting with those from diverse backgrounds. This quality of nurses being close to the patient’s everyday experience is crucial for connection and collaboration. This connection is reflected in the public perception of nurses as positive and trustworthy. A 2005 Gallup poll found that nurses top the list of most ethical professions, with Americans rating nurses among the most trusted professionals. Eighty-two percent of respondents rated nurses’ honesty and ethics as “very high” or “high,” with medical doctors in third place at 65% (Gallup, 2005).

In my experience working with graduate psychiatric nursing students, this problem-solving approach is useful but one that novice nurse psychotherapists often struggle with. Because nurses are used to taking care of people and are action oriented, beginning students often want to rescue the patient and help the patient to feel better. Helping the patient feel better is not the main goal of psychotherapy, and a focus on amelioration of symptoms may even be counterproductive to the process, although feeling better overall most likely will be a by-product of successful therapy. In a well-intended effort to help the person feel better, the nurse may be too directive, and this is antithetical to promoting empowerment. Letting the psychotherapeutic process unfold takes time, and that has typically not been a part of nursing practice, especially within the current health care system.

Holistic Model of Healing

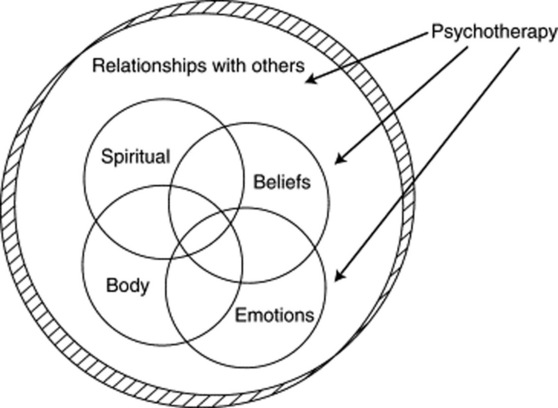

In contrast to the biomedical model goal of curing, the goal in the holistic model is healing. This is an important distinction, because curing is not always possible but healing is (Dossey et al., 2005). The word heal is an old Anglo Saxon word haelen, which means “to become whole, body, mind, and spirit within oneself,” but it can also be defined in a broader context as being in “right relationship” with oneself, others, and our world. Dossey and colleagues (2005) define healing as “the emergence of right relationship between all levels … the process of bringing together all parts of one’s self (physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, relational) at deeper levels of inner knowing, leading to an integration and balance …” (p. 236). Each component is interdependent and interrelated, based on the premise that when there is a change in one part of the system, the change reverberates in all dimensions. Minor changes in one part, such as spiritual beliefs, body, or emotions, may potentiate a change in all other spheres, as well as in the person’s relationship with others and his or her world. Conversely, a change in the context or relationships with others may create changes in other dimensions (e.g., body, emotions, spiritual and thoughts or beliefs) of the person. The context or background of this model is the person’s culture as mediated by the person’s family and relationships. Figure 1-1 shows components of the holistic model developed for psychiatric nursing.

In the holistic model, psychotherapy interventions can be designed to target any area to facilitate healing (see Figure 1-1). For example, the therapist using a cognitive-behavioral therapy model would focus on the person’s thoughts or behaviors, the therapist using an interpersonal therapy model would focus on the social context and relationships with others, and the psychodynamic therapist would assist the person in deepening his or her understanding of the past to change emotions and thoughts. A change in any arena reverberates to all other dimensions for the overall purpose of facilitating healing and wholeness.

Some of the goals of psychotherapy include the reduction of symptoms, improvement of functioning, relapse prevention, increased empowerment, and the specific collaborative goals set with the patient. It is important to note that symptom-relief is a goal within the biomedical model. Within this model, symptoms are often thought to be the enemy and the cause of the patient’s problem. Psychotropic medications target symptoms and are prescribed in an effort to eliminate the symptoms. For example, prescribing a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) to increase serotonin levels is thought to treat the underlying cause of the depressive disorder. Whether this chemical imbalance causes depression or coexists with some depressive disorders is still a matter of speculation. However, in a holistic model, symptoms are seen as a form of communication and are useful for understanding the meaning of the dysregulation and disharmony that is occurring for this person at a given time. By eliminating the symptoms with medication, we are essentially “shooting the messenger.” Psychotropic medications do have their place in treatment, especially when the patient’s functioning is impaired. However, reframing symptoms as a communication changes the way we view the relation of the problem to the person and enhances our ability to hear the meaning of the symptoms as we listen to our patient.

Requisites for Nurse Psychotherapists

Nurse psychotherapists have the honor of participating in the healing process, and as Dossey and associates (2005) point out, in the nurse-patient relationship, the nurse becomes “the patient’s environment” (p. 50). Through consciousness, intent, and presence, the nurse psychotherapist’s therapeutic use of self facilitates others in their healing. To counter the learned patterns of nursing practice (i.e., busyness, task-focused, and control), the nurse psychotherapist needs to cultivate reflection, mindfulness, and patience. The nurse psychotherapist creates a healing presence of unconditional acceptance, patience, lovingness, nonjudgmental attitude, understanding, good listening skills, honesty, and empathy. These qualities are the essence of presence (McKivergin, 1997) and allow the nurse psychotherapist to “be with” rather than “doing to” the patient. Scaer (2005), a neurologist specializing in trauma, says that presence involves a personal interaction that contributes to physiologic changes in the person. He states, “This healing, empathic presence affects and alters the parts of the brain that process pain, fear, anxiety, and distress” (p. 167). Presence may facilitate healing by modulating negative emotions by enhancing neurotransmitters and hormones that promotes optimum autonomic functioning.

According to Dossey and coworkers (2005), qualities essential for nurse healers include expansion of consciousness and continuing one’s own journey toward wholeness. This can be accomplished through many different venues: nature, relationships, counseling, meditation, mindfulness, self-awareness exercises, spiritual practices, chanting, prayer, journaling, openness to receiving one’s own healing treatments, and reflective activities such as hiking, walking, or rowing. These activities enable the nurse to enhance the development of mindfulness, patience, and authenticity. Mindfulness is a skill that can be learned through practice and discipline and can used as a tool in the psychotherapeutic process. The vast literature on the development of mindfulness crosses many disciplines and orientations, from Buddhism to psychoanalysis. Mindfulness is discussed further in Chapter 10.

Safran and Muran (2000) state that mindfulness in psychotherapy has three characteristics:

Peplau (1991) stressed the need for self-awareness in the nurse-patient relationship and stated, “The extent to which each nurse understands her own functioning will determine the extent to which she can come to understand the situation confronting the patient and the way he sees it” (p. x). However, with the rise of psychopharmacology and biologic psychiatry, self-awareness has not been a priority. Self-awareness is key to understanding others, and it reduces the likelihood that therapists will act out their own agendas and use patients for gratification or self-esteem needs. For example, one novice nurse psychotherapist was so rewarded emotionally by his work with a particular patient that he went out of his way to meet with her when she needed him and to schedule additional office hours when he would not normally be in the office. The patient responded with gratitude, which enhanced the self-esteem of the nurse who was conscientious and overly responsible for this patient. It was only through supervision that he began to understand how his need for recognition fueled the overly accommodating stance, how his objectivity about the psychotherapeutic process had been compromised, and how this cultivated an unhealthy dependency in the patient.

We all have preconceptions that are brought to every situation. It is not as important to eliminate these as to be aware of what they are and how they may influence our work. The extent of a nurse’s self-knowledge determines the extent to which s/he can understand another person. Neuroimaging studies have confirmed that being aware of another’s mind is related to a person’s ability to monitor his/her own mental state (Keenan, 2003). A person does not have to be a paragon of mental health to help another. Some feel that to be truly empathic, a person should have experienced psychological suffering, which can serve to deepen the work in psychotherapy. Personal therapy and supervision are helpful for the novice nurse psychotherapist to cultivate emotional genuineness, authenticity, and objectivity. Supervision is not therapy, but it does assist the therapist in discussing difficult cases and understanding his/her own blind spots and how personal issues may impact the therapeutic relationship. Ongoing group or individual supervision after graduation is necessary for continued growth and an ethical practice. Seasoned psychotherapists usually seek supervision and consultation throughout their professional lives. A sample of suggestions for discussion that may be covered in supervision is included in Appendix I-1 (p. 131).

Irvin Yalom (2002) cogently makes a case for therapy for the therapist:

In addition to self-awareness, self-care is fundamental in caring for others. When a flight takes off, the airline attendant announces that all adults must put the oxygen mask over their faces first before securing the mask on a child. This is an appropriate metaphor for all caregivers. Much has been written about the trauma inherent in nursing. Various terms have been used to describe this phenomenon, such as burnout, compassion fatigue, and vicarious or secondary traumatization. Burnout may occur for many reasons: our collective history as a profession of women, the patriarchal medical system and nurses’ subservient role, stressful health care environments, and caring for and witnessing trauma and pain in others. Most often, recognition of personal and professional trauma is unrecognized and therefore unaddressed. Sequelae of trauma may include emotional numbing, detachment, hypervigilance, perfectionism, controlling behaviors, emotional lability, attentional problems, and low self-esteem, all of which mitigate the ability to adopt the psychotherapeutic stance necessary for conducting psychotherapy. It is only in the recognition of one’s own trauma that s/he can transcend it and be of help to others (Conti-O’Hare, 2002).

Elements of Psychotherapy

Caring

Caring has been identified as central to nursing and as the foundation for practice (Dossey, 2005; Morse et al., 1990; Schoenhofer, 2002). Caring encompasses and expands Carl Rogers’ idea of unconditional positive regard that has been adopted by most disciplines as essential in helping relationships (Rogers, 1951). A phenomenologic study delineated the characteristics of the advanced practice nurse-patient relationship that are foundational to caring (Thomas et al., 2005). They include the mutuality of nonromantic love based on a genuine knowing of the person, trust, and respect reflected in an acceptance of and authentic appreciation for the other. Every person is approached with acceptance and unconditional love with the nurse and patient as co-participants in the process of healing. Inherent in caring is respect for the autonomy and agency of the other person. Fundamental to caring is the understanding of another person’s unique configuration of attitudes, feelings, and values from that person’s perspective.

Research has found that spirituality emerges as a significant theme in caring and is related to a deepening sense of patients’ inner peace, emotional well-being, and hope in the context of personal crisis (Edmands et al., 1999). Caring results in enhanced personhood for the nurse and the patient. The authors of the study speculate that the personhood of the patient is enhanced because of the advanced practice nurse’s ability to address all domains—behavioral, psychosocial, addictive, psychosomatic, and mental health care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree