The Nurse in the Schools

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Discuss professional standards expected of school nurses.

2. Differentiate between the many roles and functions of school nurses.

3. Describe the different variations of school health services and coordinated school health programs.

Key Terms

advanced practice nurse, p. 916

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), p. 916

Americans with Disabilities Act, p. 915

case manager, p. 917

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, p. 918

Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004, p. 915

community outreach, p. 918

consultant, p. 917

counselor, p. 917

crisis teams, p. 926

direct caregiver, p. 917

do-not-resuscitate orders, p. 930

emergency plan, p. 923

health educator, p. 917

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), p. 922

individualized education plans (IEPs), p. 915

individualized health plans (IHPs), p. 915

National Association of School Nurses, p. 915

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, p. 915

PL 93-112 Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, p. 915

PL 94-142 Education for All Handicapped Children Act, p. 915

PL 105-17 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), p. 915

primary prevention, p. 920

researcher, p. 918

Safe Kids Campaign, p. 921

school-based health centers, p. 919

School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006, p. 917

school-linked program, p. 920

secondary prevention, p. 920

standard precautions, p. 924

tertiary prevention, p. 920

—See Glossary for definitions

Lisa Pedersen Turner, RN, MSN, PCHCNS-BC

Lisa Pedersen Turner, RN, MSN, PCHCNS-BC

Lisa Pedersen Turner is the clinic coordinator of the Good Samaritan Nursing Center as well as a clinical instructor for public health nursing at the University of Kentucky. Her work at the Good Samaritan Nursing Center has focused on providing school health services to underserved populations as well as developing a K-12 school health curriculum for a county in rural Kentucky. She has lectured and supervised students studying public health nursing in a myriad of community settings, including school clinics, homeless shelters, and free clinics for adults and children. She has contributed to several projects to evaluate school health services and has presented at national and international symposia on nursing clinics in the community.

In 2010 over 49.4 million children attended one of 132,700 schools every day (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2010). These children need health care during their school day, and this is the job of the school nurse. There are approximately 45,000 school nurses in the public schools alone (American Federation of Teachers, 2008). Even parents expect a school nurse to be available for their children at school (Read et al, 2009).

It is commonly thought that school nurses only put bandages on cuts and soothe children with stomachaches. However, that is not their major role. School nurses give comprehensive nursing care to the children and the staff at the school. At the same time, they coordinate the health education program of the school and consult with school officials to help identify and care for other persons in the school community.

The school nurse provides care to the children not only in the school building itself, but also in other settings where children are found—for example, in juvenile detention centers, in preschools and daycare centers, during field trips, at sporting events, and in the children’s homes (Nic Philibin et al, 2010).

The school nurse, therefore, must be flexible in giving nursing care, education, and help to those who need it. This chapter discusses the history of nursing in the schools and the functions of school nurses today. In addition, the standards of practice for school nurses are discussed, as the nurse takes on a variety of roles. Different types of school health services are reviewed, including government-financed programs.

The primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of nursing care that nurses give to children in the schools are presented. The most common health problems that the school nurse finds in children are also discussed under their appropriate prevention levels. The chapter ends with a discussion of the ethical dilemmas that may arise for school nurses. The future of nursing in the schools is predicted for ever-changing communities.

History of School Nursing

The history of school nursing began with the earliest efforts of nurses to care for people in the community. In the late 1800s in England, the Metropolitan Association of Nursing provided medical examinations for children in the schools of London. By 1892 nurses in London were responsible for checking the nutrition of the children in the schools (Anonymous, 2008). These ideas spread to the United States where, in 1897, nurses in New York City schools began to identify ill children. They then excluded these children from classes so that other children would not be infected (Vessey and McGowan, 2006). Health education was also important during this time. Many states had laws in the late 1800s mandating that nurses teach within the schools about the abuse of alcohol and narcotics (Fee and Liping, 2007).

In the early 1900s in the United States, the main health problem in the community was the spread of infectious diseases. On October 2, 1902, in New York City, Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement nurses began going into homes and schools to assess children. These public health nurses were at first in only four schools caring for about 10,000 children. They made plans to identify children with lice and other infestations and those with infected wounds, tuberculosis (TB), and other infectious diseases (Vessey and McGowan, 2006; Judd, Sitzman, and Davis, 2009).

The need for school nurses was immediately recognized by the health care community. By 1910, Teachers College in New York City added a course on school nursing to their curriculum for nurses. In 1916 a school superintendent requested that a public health nurse be sent to the schools to care for children of immigrants (Judd, Sitzman, and Davis, 2009). By the 1920s school nurse teachers were employed by most municipal health departments. As the years went by and communities struggled with serious economic issues and hardships during the Depression, school nurses continued to provide health care to children in the schools through the federal Works Progress Administration program (WPA) (Judd, Sitzman, and Davis, 2009).

In the 1940s the nurses were mostly employed by the school districts directly. The nurses also provided home nursing and health education for the children and their parents (Vessey and McGowan, 2006). In addition, school nurses became concerned with the condition of school buildings (Judd, Sitzman, and Davis, 2009).

After World War II and into the 1950s, as a result of the increased use of immunizations and antibiotics, the number of children with communicable disease in the schools fell. School nurses then turned their attention to screening children for common health problems and for vision and hearing. School nurses were less likely to teach health concepts in the children’s classrooms and more likely to consult with teachers about health education (Vessey and McGowan, 2006). However, there was an increased emphasis on employee health, and school nurses began screening teachers and other school staff for health problems (Fee and Liping, 2007).

The 1960s saw an upsurge in the call for higher levels of education for school nurses. A position paper delivered at the 1960 American Nurses Association (ANA) convention called for the Bachelor of Science in nursing degree as the minimum educational preparation for school nurses. By 1970 the first school nurse practitioner program was started at the University of Colorado. There, school nurses learned advanced concepts of school nursing practice to provide primary health care to children (Vessey and McGowan, 2006).

Federal Legislation in the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s

Community involvement in health in schools was a major thrust in the 1970s and 1980s. Counseling and mental health services were added to the responsibilities of school nurses, who began to directly teach children concepts of health. Children were no longer just being screened for illnesses (Vessey and McGowan, 2006). Because of federal laws that required schools to make accommodations for handicapped children, medically fragile children were attending schools, often for the first time. One of these laws, PL 93-112 Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, was an important step in helping all children enjoy a normal educational experience (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010). This law was followed by PL 94-142 Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which required that children with disabilities have services provided for them in the schools.

Following the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1992, PL 105-17 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) passed in 1997. Both of these laws required that more children be allowed to attend schools. Schools had to make allowances for their special needs, which included ensuring that their school experience was in balance with their health care needs by developing individualized education plans (IEPs) and individualized health plans (IHPs). That meant that more children with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), chronic illnesses, or mental health problems were in the classrooms and needed more attention from the school nurse (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010). The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 requires a healthy environment in the schools, which also affects children who have health problems (Adler, 2009). Table 42-1 summarizes the effects of these laws on school nurses and schoolchildren.

TABLE 42-1

FEDERAL LEGISLATION AFFECTING SCHOOL NURSING

| LAW | EFFECT ON SCHOOL NURSES AND CHILDREN |

| 1973: PL 39-112, Section 504 of Rehabilitation Act | Children cannot be excluded from schools because of a handicap. The school must provide health services that each child needs. |

| 1975: PL 94-142, Education for All Handicapped Children Act | All children should attend school in least restrictive environment. Requires school district’s committee on handicapped to develop individualized education plans (IEPs) for children. |

| 1992: Americans with Disabilities Act | Persons with disabilities cannot be excluded from activities. |

| 1997: PL 105-17, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) | Educational services must be offered by schools for all disabled children from birth through age 22 years. |

| 2001: No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 | All children must receive standardized education in a healthy environment. |

| 2004: Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 | Every local education agency (LEA) participating in federal school meal programs must establish a local school wellness policy. |

Compiled from Betz CL: Use of 504 plans for children and youth with disabilities: nursing application, Pediatr Nurs 27:347-352, 2001; Whalen LG, Grunbaum JA, Kann L, et al: Profiles 2002. School health profiles. Surveillance for characteristics of health programs among secondary schools, Washington, DC, 2004, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USDHHS.

Also during the 1990s, the responsibilities of the school nurse were extended to include the development of complete clinics and health care agency centers within or attached to the schools (Vessey and McGowan, 2006). These school-based clinics will be discussed later in this chapter. By 2002, some school nurses were responsible for several schools, and they provided care under a variety of nursing roles. To address obesity and to promote healthy eating and physical activity through changes in school environments, Congress passed the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 (PL 108.265 Section 204). This act designated that each local education agency (LEA) participating in federal school meal programs, such as the National School Lunch or Breakfast Program, must establish a local school wellness policy. Table 42-2 gives the highlights of school nursing history over the last century.

TABLE 42-2

HIGH POINTS IN SCHOOL NURSING HISTORY

| DECADE | MAJOR EVENTS IN SCHOOL NURSING |

| 1890s | English and American nurses are used in schools to examine children for infectious diseases and to teach about alcohol abuse. |

| 1900s | Henry Street Settlement in New York City sends nurses into schools and homes to investigate children’s overall health. |

| 1910s | School nursing course added to Teachers College nursing program. |

| 1920s and 1930s | School nurses are employed by community health departments. |

| 1940s | School districts employ school nurses. |

| 1950s | Children are screened in schools for common health problems. |

| 1960s | Educational preparation for school nurses is debated. |

| 1970s | School nurse practitioner programs begun. Increased emphasis put on mental health counseling in schools. |

| 1980s | Children with long-term illness or disabilities attend schools. |

| 1990s | School-based and school-linked clinics are started. Total family and community health care is offered. |

| 2000s | School nurses give comprehensive primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of nursing care. |

From Schlachta-Fairchild L, Varghese SB, Deickman A, Castelli D: Telehealth and telenursing are live: APN policy and practice implications, J Nurse Pract 6:98-106, 2010.

Standards of Practice For School Nurses

The professional body for school nurses is the National Association of School Nurses (NASN), headquartered in Washington, DC. This association provides the general guidelines and support for all school nurses. It revised the standards of professional practice for school nurses in 2001. These standards require that all school nurses use the nursing process throughout their practice: assessment, analysis, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

In addition, the professional standards rely on nurses to give care based on 11 criteria (NASN, 2001). These criteria include the ability to do the following:

• Develop school health policies and procedures.

• Evaluate their own nursing practice.

• Keep up with nursing knowledge.

• Interact with the interprofessional health care team.

• Ensure confidentiality in providing health care.

• Consult with others to give complete care.

• Use research findings in practice.

• Ensure the safety of children, including when delegating care to other school personnel.

• Have good communication skills.

• Manage a school health program effectively.

In general, the NASN standards (Box 42-1) compare very well with those developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) regarding giving health care to students in the schools. The AAP (2008a) developed their own ideas about how nurses function in schools based on their assessment of schoolchildren’s health needs. These guidelines are similar to those written by the NASN. The AAP stated that school nurses should ensure the following:

• That children get the health care they need, including emergency care in the school

• That the nurse keeps track of the state-required vaccinations that children have received

• That the nurse carries out the required screening of the children based on state law

• That children with health problems are able to learn in the classroom

The AAP recommends that the nurse be the head of a health team that includes a physician (preferably a pediatrician), school counselors, the school psychologist, members of the school staff including the administrator, and teachers. The goal is for children to get complete health care in the schools.

Educational Credentials of School Nurses

The NASN recommends that school nurses be registered nurses who also have bachelor’s degrees in nursing and a special certification in school nursing (NASN, 2001). The AAP has the same recommendations (AAP, 2008a). However, not all nurses have been educated this way. There are no general laws regarding the educational background of school nurses. School nurses in some states are required to be registered nurses, but licensed practical nurses are also seen in some schools. Box 42-2 lists the states that have laws regarding the education of school nurses. Only about half of all U.S. states require some form of additional study for school nurse specialty certification (CDC, 2006).

School nurses in some schools may be advanced practice nurses who specialize in caring for children. They may be nurse practitioners that have specialized in child health nursing (pediatrics), in family nursing, or in the school nurse practitioner role. Clinical nurse specialists who are school nurses may also be found in child health nursing or community or public health nursing. The higher the educational level of the school nurse, the better that nurse is able to give complete care to children and their families. These advanced practice nurses may be certified by professional organizations such as the ANA or their own professional organization. Most hold master’s degrees in nursing.

School nurses do not start their nursing careers in the schools. All have prior experience in nursing—most from working either in hospitals or with communities. In addition, most have spent years working with children, so they are aware of their special health needs.

Roles and Functions of School Nurses

School nurses give care to children as direct caregivers, educators, counselors, consultants, and case managers. They must coordinate the health care of many students in their schools with the health care that the children receive from their own health care providers.

In Healthy People 2020 Proposed Objectives, goal ECBP HP2020-4 states that there should be 1 nurse for every 750 children in each school (USDHHS, 2010). Most schools have not achieved this objective. By 2006 approximately 45% of the nation’s schools met that standard (CDC, 2010a). A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2006), the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006 (SHPPS 2006), found that by 2006 several states (Alabama, Arizona, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming) specified a maximum student-to-school nurse ratio. Three states (Delaware, District of Columbia, and New Jersey) required schools to have a full-time school nurse. Having fewer nurses in the schools means that the nurses are expected to perform many different functions. It is therefore possible that they are unable to give the amount of comprehensive care that the students need (Ficca and Welk, 2006).

In 2003 the National Association of School Nurses adopted a resolution recommending that there be a school nurse at all times in every school. The recommendation was based on requirements of the IDEA Act and CDC health recommendations (NASN, 2003).

School Nurse Roles

Direct Caregiver

The school nurse is expected to give immediate nursing care to the ill or injured child or school staff member. Direct caregiver is the traditional role of the school nurse.

Although most school nurses are in public or private schools and give care only during school hours, the nurse in a boarding school provides nursing care to children 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. In boarding schools, the children live at school and go home only for vacations. The nurse also lives at the school and may be on call all the time. The nurse in the boarding school is very important to the children because this nurse is the gatekeeper to their complete health care (Thackaberry, 2001). The nurse makes all of the health care decisions for the child and has a referral system to contact other health care providers, such as physicians and psychological counselors, if needed.

Health Educator

The school nurse in the health educator role may be asked to teach children both individually and in the classroom. The nurse uses different approaches to teach about health, such as teaching proper nutrition or safety information. Many school nurses teach the older elementary girls and boys about the coming changes in their bodies as puberty arrives. Other school nurses may teach the health education classes that are required by the states to be included in the programs.

Case Manager

The school nurse is expected to function as a case manager, helping to coordinate the health care for children with complex health problems. This may include the child who is disabled or chronically ill and who may be seen by a physical therapist, an occupational therapist, a speech therapist, or another health care provider during the school day. The nurse sets up the schedule for the child’s visits so that those appointments do not unnecessarily impact negatively on the child’s academic day.

Consultant

The school nurse is the person best able to provide health information to school administrators, teachers, and parent–teacher groups. As a consultant, the school nurse can provide professional information about proposed changes in the school environment and their impact on the health of the children. The nurse can also recommend changes in the school’s policies or engage community organizations to help make the children’s schools healthier places (Nic Philibin et al, 2010). This is a population-level role for the school nurse; the population consists of all children, families, staff, and the surrounding community.

Counselor

The school nurse may be the person whom children trust to tell important secrets about their health. It is important that, as a counselor, the school nurse have a reputation as being a trustworthy person to whom the children can go if they are in trouble or if they need to confide about a personal matter (Nic Philibin et al, 2010). Nurses in this situation should tell children that if anything they reveal points out that they are in danger, the parents and school officials must be told. However, privacy and confidentiality, as in all health care, are important.

In addition, the school nurse may be the person to help with grief counseling in the schools. (See later discussion on the school crisis team.)

Community Outreach

When participating in community outreach, nurses can be involved in community health fairs or festivals in the schools, using that opportunity to teach others. They can be part of an influenza immunization program for the school staff and can promote a health education fair and do blood pressure screenings. They can initiate a liaison, coordinating with local health charities to provide education to the schools (Hamner, Wilder, and Byrd, 2007).

Researcher

Little research has been done on nurses caring for children in the schools. The school nurse is responsible for making sure that the nursing care given is based on solid, evidence-based practice. Outcomes regarding school nurse services need to be studied (Nic Philibin et al, 2010). Therefore, the school nurse, as an educator, is in the right position to do studies as a researcher that advances school nursing practice.

School Health Services

School health services vary in their scope. However, there are common parts to the programs.

Federal School Health Programs

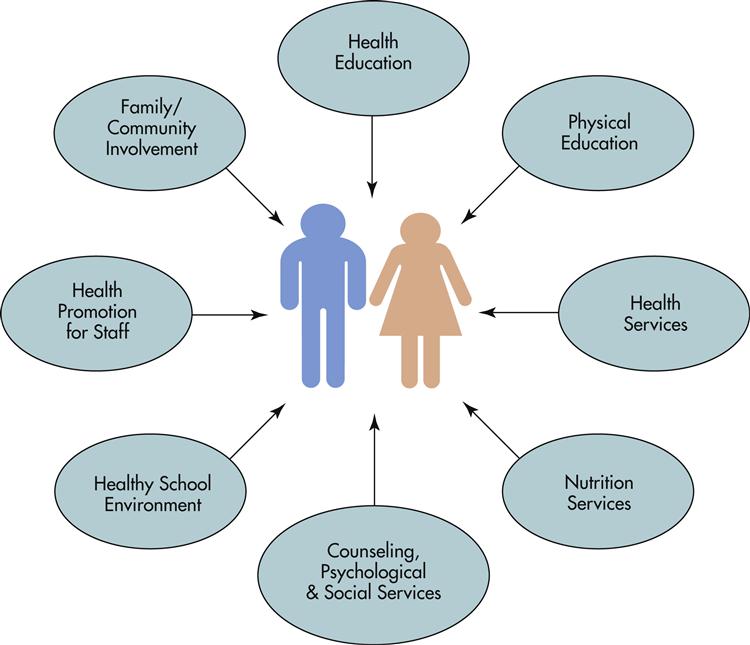

The federal government, through the coordination of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has developed a plan that school health programs should follow (CDC, 2008) (Figure 42-1).

This plan was originally developed in 1987 after the CDC began funding schools for HIV-prevention education programs. By 1992 this educational system was so successful that it was expanded to include school health programs to teach children prevention of other chronic illnesses. These include diseases caused in part by risk factors such as poor diet, lack of exercise, and smoking.

Then, in 1998, the government expanded the program again to include a more complete school health education program that included the parents and the community in the children’s care. By 2009, 22 states had been funded for their school health programs by the CDC (CDC, 2009b). The funding has paid for the development of health education plans of study, or curricula, that include policies, guidelines, and training for these health programs. The states then use these courses to teach the children. The schools are actively involved in helping the children practice problem solving, communication, and other life skills so they can reduce their risk factors.

According to the CDC, two states in particular have been very successful with these programs. West Virginia has developed a program called the Instructional Goals and Objectives for Health Education and Physical Education, which increased the ability of the children to pass the President’s Physical Fitness Test. In Michigan, the Governor’s Council on Physical Fitness, Health, and Sports developed an Exemplary Physical Education Curriculum project that made up educational materials and plans for children to achieve high physical fitness scores. All of these programs were paid for by the federal school health program funding (CDC, 2009b).

School Health Policies and Program Study 2006

After the CDC began funding educational programs about prevention of HIV in the schools in 1987, there was clearly a need to expand these programs. By 1992 the CDC began giving money to fund other school health programs that taught students about heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and substance abuse prevention (Kann, Brener, and Wechsler, 2007). These programs have been evaluated by the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006 (CDC, 2006), which looked at all eight parts of the school health program in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The study found that only half of the states had the recommended 1 school nurse for every 750 students that was discussed earlier in this chapter. It also found that most school health programs had access to mental health counselors, but that the food in the schools’ cafeteria tended to be high in salt and fat. Most schools had rules forbidding weapons on the school grounds or use of tobacco. Parental involvement in the school health programs was only about 50% and, to make a difference in a child’s health, parents are encouraged to be involved (Kann, Brener, and Wechsler, 2007).

School-Based Health Programs

Because many schoolchildren may not receive health care services other than screening and first aid care from the school nurse, the U.S. government began funding school-based health centers (SBHCs) during the 1990s. These are family-centered, community-based clinics run within the schools. These clinics give expanded health services, including mental health and dental care, as well as the more traditional health care services (Brown and Bolen, 2008). The SBHCs can range in size from small to large; some school clinics are open to the community only during the school year and others are open 24 hours a day all year round. An example of the more limited clinic is the SBHC in Worchester, MA, where six clinics are run in the schools (elementary through high school) by the Family Health Center of Worchester, Inc during the school year months of August through May (Family Health Center, 2010).

Another example of a clinic is the school-linked program, which is coordinated by the school but has community ties (Brown, 2008). An example of this is the Collaborative Model for School Health in Pitts County, North Carolina. The nurses employed by the local hospital in that area provide health care for children in kindergarten through fifth grade. There is collaboration between the county health department, the local university’s nursing school, and other private health care providers to give primary, secondary, and tertiary nursing care. An evaluation of the program has shown that the children’s school attendance and learning has increased as a result of the presence of more complete school health services (Trapp, 2010).

At a center in Texas, an urban SBHC is located in a school district where many of the children lack health insurance. The school nurses there are assisted by three part-time nurse practitioners and one public health nurse. The school nurse is responsible for the record keeping on the children’s immunizations, does the screening, and gives first aid to injured children. Then the school nurse refers children who need additional health care to the SBHC in the school. Parents like the program because they trust the school nurse. They also like its location inside the school because everyone can receive health care without having to travel far to get to a clinic (Texas Association of School-Based Health Centers, 2010).

School Nurses And Healthy People 2020

Many Healthy People 2020 proposed objectives are directed toward the health of children. In addition, several point directly at the care that nurses give to children in the schools. The Healthy People box lists the objectives that involve school-age children. These objectives are concerned with the children with disabilities in the schools, the number of children with major health problems, and the ratio of nurses to children in the schools. Nurses can accomplish the goals using the three levels of prevention, as discussed next.