The Nurse in Occupational Health

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Describe the nursing role in occupational health.

2. Discuss current trends in the U.S. workforce.

3. Give examples of work-related illness and injuries.

4. Use the epidemiological model to explain work-health interactions.

7. Complete an occupational health history.

8. Differentiate between the functions of OSHA and NIOSH.

9. Explain an effective disaster plan in occupational health.

Key Terms

agents, p. 942

environments, p. 935

Hazard Communication Standard, p. 953

host, p. 941

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, p. 953

National Occupational Research Agenda, p. 953

occupational and environmental health nursing, p. 936

occupational health hazards, p. 949

occupational health history, p. 948

work-health interactions, p. 935

workers’ compensation, p. 953

worksite walk-through, p. 949

—See Glossary for definitions

Bonnie Rogers, DrPH, COHN-S, LNCC, FAAN

Bonnie Rogers, DrPH, COHN-S, LNCC, FAAN

Bonnie Rogers is a Professor of Nursing and Public Health and is Director of the North Carolina Occupational Safety and Health Education and Research Center and the Occupational Health Nursing Program at the University of North Carolina School of Public Health, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Dr. Rogers received her diploma in nursing from the Washington Hospital Center School of Nursing, Washington, DC; her baccalaureate in nursing from George Mason University, School of Nursing, Fairfax, Virginia; and her master of public health degree and doctorate in public health, the latter with a major in environmental health sciences and occupational health nursing from the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland. She holds a postgraduate certificate as an adult health clinical nurse specialist. She is a certified occupational health nurse and legal nurse consultant as well as a fellow in the American Academy of Nursing and the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses. In addition to managerial, consultant, and educator/researcher positions, Dr. Rogers has also practiced for many years as a public health nurse, occupational health nurse, and occupational health nurse practitioner. She has published more than 175 articles and book chapters and two books, including Occupational Health Nursing: Concepts and Practice and Occupational Health Nursing Guidelines for Primary Clinical Conditions. She is Associate Editor for the Legal Nurse Consulting Principles and Practices core book, and is Editor of the Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting. She is a member of several editorial panels and has given more than 450 presentations nationally and internationally on occupational health and safety issues. Dr. Rogers has had several funded research grants on clinical issues in occupational health, health promotion, research priorities, hazards to health care workers, and ethical issues in occupational health. She was invited to study ethics as a visiting scholar at the Hastings Center in New York and was granted a NIOSH career award to study ethical issues in occupational health. Dr. Rogers is a strong advocate of occupational health research and has served as Chairperson of the NIOSH National Occupational Research Agenda Liaison Committee for nearly 15 years. She has served on numerous Institute of Medicine committees including Vice Chairperson for the Protection for Healthcare Workers in the Workplace Against Novel H1N1 Influenza A. She is currently a member of the first IOM standing committee on Personal Protective Equipment for Workplace Safety and Health. Dr. Rogers is past president of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses as well as the Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics. She completed several terms as an appointed member of the National Advisory Committee on Occupational Safety and Health and was recently elected Vice President of the International Commission on Occupational Health. She is a consultant in occupational health and ethics.

Nurses provide care to individuals to help them achieve optimal health; yet, at the same time in the course of their work, nurses face numerous hazardous substances such as blood, body fluids, or chemicals and often must lift heavy loads. Work can be both fulfilling and hazardous or risky. Many changes have occurred in the nature of work and workplace risks, the work environment, workforce composition and demographics, and health care delivery mechanisms. An analysis of the trends suggests that work-health interactions will continue to grow in importance, affecting how work is done, how hazards are controlled or minimized, and how health care is managed and integrated into workplace health delivery strategies. Although some workers may never face more than minor adverse health effects from exposures at work, such as occasional eyestrain resulting from poor office lighting, every industry has grappled with serious hazards (USDHHS, NIOSH, 2010).

In America, work is viewed as important to one’s life experiences, and most adults spend about one third of their time at work (Rogers, 2011). Work—when fulfilling, fairly compensated, healthy, and safe—can help build long and contented lives and strengthen families and communities. No work is completely risk free, and all health care professionals should have some basic knowledge about workforce populations, work and related hazards, and methods to control hazards and improve health.

Important developments are occurring in occupational health and safety programs designed to prevent and control work-related illness and injury and to create environments that foster and support health-promoting activities. Occupational health nurses have performed critical roles in planning and delivering worksite health and safety services, which must continue to grow as comprehensive and cost-effective services. In addition, the continuing increase in health care costs and the concern about health care quality have prompted the inclusion of primary care and management of non–work-related health problems in the health services’ programs. In some settings, family services are also provided.

Health at work is an important issue for most individuals for whom the nurse provides care. With many individuals spending so much time at work, the workplace has significant influence on health and can be a primary site for the delivery of health promotion and illness prevention. The home, the clinic, the nursing home, and other community sites such as the workplace will become the dominant areas where health and illness care will be sought (USDHHS/CDC/NIOSH, 2009).

This chapter describes the nurse’s role in occupational health—working with employees and the workforce population. The focus is on the knowledge and skills needed to promote the health and safety of workers through occupational health programs, recognizing work-related health and safety and the principles for prevention and control of adverse work-health interactions. The prevalence and significance of the interactions between health and work underscore the importance of including principles of occupational health and safety in nursing practice. The types of interactions and the frequent use of the general health care system for identifying, treating, and preventing occupational illnesses and injuries require nurses to use this knowledge in all practice settings. The Epidemiologic Triangle is used as the model for understanding these interactions, as well as risk factors, and effective nursing care for promoting health and safety among employed populations.

Definition and Scope of Occupational Health Nursing

Adapted from the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses (AAOHN) (2004), occupational and environmental health nursing is the specialty practice that focuses on the promotion, prevention, and restoration of health within the context of a safe and healthy environment. It includes the prevention of adverse health effects from occupational and environmental hazards. It provides for and delivers occupational and environmental health and safety programs and services to clients. Occupational and environmental health nursing is an autonomous specialty, and nurses make independent nursing judgments in providing health care services.

The foundation for occupational and environmental health nursing is research based. Recognizing the legal context for occupational health and safety, this specialty practice derives its theoretical, conceptual, and factual framework from a multidisciplinary base including, but not limited to:

• Public health sciences such as epidemiology and environmental health

• Occupational health sciences such as toxicology, safety, industrial hygiene, and ergonomics

• Social and behavioral sciences

Guided by an ethical framework made explicit in the AAOHN Code of Ethics, occupational and environmental health nurses encourage and enable individuals to make informed decisions about health care concerns. Confidentiality of health information is integral and central to the practice. Occupational and environmental health nurses are advocates for client(s), fostering equitable and quality health care services and safe and healthy environments in which to work and live.

History and Evolution of Occupational Health Nursing

Nursing care for workers began in 1888 and was called industrial nursing. A group of coal miners hired Betty Moulder, a graduate of the Blockley Hospital School of Nursing in Philadelphia (now Philadelphia General Hospital), to take care of their ailing co-workers and families (AAOHN, 1976). Ada Mayo Stewart, hired in 1885 by the Vermont Marble Company in Rutland, Vermont, is often considered the first industrial nurse. Riding a bicycle, Miss Stewart visited sick employees in their homes, provided emergency care, taught mothers how to care for their children, and taught healthy living habits (Felton, 1985). In the early days of occupational health nursing, the nurse’s work was family centered and holistic.

Employee health services grew rapidly during the early 1900s as companies recognized that the provision of worksite health services led to a more productive workforce. At that time, workplace accidents were seen as an inevitable part of having a job. However, the public did not support this attitude, and a system for workers’ compensation arose that remains today (McGrath, 1945).

Industrial nursing grew rapidly during the first half of the twentieth century. Educational courses were established, as were professional societies. By World War II there were approximately 4000 industrial nurses (Brown, 1981). The American Association of Industrial Nursing (AAIN) (now called the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses) was established as the first national nursing organization in 1942. The aim of the AAIN was to improve industrial nursing education and practice and to promote interprofessional collaborative efforts (Rogers, 1988).

Passage of several laws in the 1960s and 1970s to protect workers’ safety and health led to an increased need for occupational health nurses. In particular, the passing of the landmark Occupational Safety and Health Act in 1970, which created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), discussed later in this chapter, resulted in a great need for nurses at the worksite to meet the demands of the many standards being implemented. Under OSHA, the Act focuses primarily on protecting workers from work-related hazards. NIOSH focuses on education and research. In 1988 the first occupational health nurse was hired by OSHA to provide technical assistance in standards development, field consultation, and occupational health nursing expertise. In 1993 the Office of Occupational Health Nursing was established within the agency. In addition to direct health care delivery, nurses are more engaged than ever in policy making and management of occupational health services. In addition, in 1998, the AAOHN adopted the concept of environmental health as a significant component of the practice field. To this end, AAOHN has incorporated the term “environmental” as in occupational and environmental health nurse, in its documents and publications. In 1999, AAOHN published its first set of competencies in occupational health nursing, which have been updated, and established the AAOHN Foundation to support education, research, and leadership activities in occupational health nursing. Role expansion includes environmental health and forging sustainable relationships in the community to better improve worker health.

Roles and Professionalism in Occupational Health Nursing

As U.S. industry has shifted from agrarian (agriculture) to industrial to highly technological processes, the role of the occupational health nurse has continued to change. The focus on work-related health problems now includes the spectrum of human responses to multiple, complex interactions of biopsychosocial factors that occur in community, home, and work environments. The customary role of the occupational health nurse has extended beyond emergency treatment and prevention of illness and injury to include the promotion and maintenance of health, overall risk management, care for the environment, and efforts to reduce health-related costs in businesses. The interprofessional nature of occupational health nursing has become more critical as occupational health and safety problems require more complex solutions. The occupational health nurse frequently collaborates closely with multiple disciplines and industry management, as well as with representatives of labor.

Occupational health nurses constitute the largest group of occupational health professionals. The most recent national survey of registered nurses indicates that there are approximately 22,000 licensed occupational health nurses (HRSA, 2006). Occupational health nurses hold positions as nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, managers, supervisors, consultants, educators, and researchers. Data also show that approximately 60% of occupational health nurses report that they are employed in single-managed occupational health nurse units in a variety of businesses. The occupational health nursing role requires the nurse to adapt to an organization’s needs as well as to the needs of specific groups of workers.

The professional organization for occupational health nurses is the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses. The AAOHN’s mission is comprehensive. It supports the work of the occupational health nurse and advances the specialty. The AAOHN also does the following:

• Promotes the health and safety of workers

• Defines the scope of practice and sets the standards of occupational health nursing practice

• Develops the code of ethics for occupational health nurses with interpretive statements

• Promotes and provides continuing education in the specialty

• Advances the profession through supporting research

• Responds to and influences public policy issues related to occupational health and safety

The AAOHN provides the Standards of Occupational and Environmental Health Nursing Practice to define and advance practice and provide a framework for practice evaluation. The AAOHN Code of Ethics lists five code statements based on the goal of occupational and environmental health nurses to promote worker health and safety (AAOHN, 2004). Both documents can be obtained from the AAOHN at http://www.aaohn.org.

Occupational health nurses have many roles, such as clinician, case manager, coordinator, manager, nurse practitioner, corporate director, health promotion specialist, educator, consultant, and researcher (AAOHN, 2007). The majority of occupational health nurses work as solo clinicians, but increasingly additional roles are being included in the specialty practice. In many companies, the occupational health nurse has assumed expanded responsibilities in job analysis, safety, and benefits management. Many occupational health nurses also work as independent contractors or have their own businesses that provide occupational health and safety services to industry, as well as consultation.

Ethical conflict is nothing new in occupational and environmental health nursing practice. Traditional concerns about confidentiality of employee health records, hazardous workplace exposures, issues of informed consent, risks and benefits, and dual duty conflicts are now married with newer concerns of genetic screening, worker literacy and understanding, work organization issues, and untimely return to work (Rogers, 2011). With the current changes in health care delivery and the movement toward managed care, occupational health nurses will need increased skills in primary care, health promotion, and disease prevention. The aim of the occupational health nurse will be to devote much attention to keeping workers and, in some cases, their families healthy and free from illness and worksite injuries. Specializing in the field is often a requirement.

Academic education in occupational health and safety is generally at the graduate level. Training grants from NIOSH support Master’s and doctoral education with emphases in occupational health nursing, industrial hygiene, occupational medicine, and safety. These programs, listed in Box 43-1, are offered through Occupational Safety and Health Education and Research Centers throughout the country. Certification in occupational health nursing is provided by the American Board for Occupational Health Nurses (ABOHN). ABOHN offers two basic certifications: the COHN (Certified Occupational Health Nurse) and COHN-S (Certified Occupational Health Nurse–Specialist). Eligibility for the COHN requires licensure as a registered nurse, whereas the COHN-S requires RN licensure plus a baccalaureate degree. In addition, certification is achieved through experience, continuing education, professional activities, and examination. Those interested in certification can view the requirements on the ABOHN website (www.abohn.org).

Workers as A Population Aggregate

The population of the United States was expected to increase from approximately 281.4 million people in 2000 to an estimated 335 million by the year 2025 (Hollmann, Mulder, and Kallan, 2000). In reality, the population had grown to 307 million plus by 2009 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). By 2010 the U.S. population had become older, with the greatest growth among those older than age 65, and a reduction in those younger than 25. Since 1995 there has been a dramatic increase in the number of workers older than 55 (Mosisa and Hipple, 2006). Between 1977 and 2007, employment of older workers over age 65 increased by 101% compared with 59% of the total employment (BLS, 2008c). BLS (2008a) data show total workforce projection to increase by 8.5% from 2006 to 2016 with workers aged 55 to 64 increasing by 36.5% and those over 65 years of age increasing by 80%. By 2016 workers older than 65 will comprise 6.1% of the labor force, up from 3.6% in 2006. The number of adults age 65 years and older is expected to more than double between now and the year 2050. By that year, one in five Americans will be an older adult.

In 2005 there were more than 131.6 million civilian wage and salary workers in the United States, employed in about 63,000 different worksites (BLS, 2007). More than 91% of those who are able to work outside of the home do so for some portion of their lives. Neither of these statistics indicates the full number of individuals who have potentially been exposed to work-related health hazards. Although some individuals may currently be unemployed or retired, they continue to bear the health risks of past occupational exposures. The number of affected individuals may be even larger, as work-related illnesses are found among spouses, children, and neighbors of exposed workers.

Americans are employed in diverse industries that range in size from one to tens of thousands of employees. Types of industries include traditional manufacturing (e.g., automotive and appliances), service industries (e.g., banking, health care, and restaurants), agriculture, construction, and the newer high-technology firms, such as computer chip manufacturers. Approximately 95% of business organizations are considered small, employing fewer than 500 people (BLS, 2005a). Although some industries are noted for the high degree of hazards associated with their work (e.g., manufacturing, mines, construction, and agriculture), no worksite is free of occupational health and safety hazards. In addition, the larger the company, the more likely it is that there will be health and safety programs for employees. Smaller companies are more apt to rely on external community resources to meet their needs for health and safety services.

Characteristics of the Workforce

The U.S. workplace has been changing rapidly (BLS, 2005a). Jobs in the economy continue to shift from manufacturing to service. Longer hours, compressed workweeks, shift work, reduced job security, and part-time and temporary work are realities of the modern workplace. New chemicals, materials, processes, and equipment are developed and marketed at an ever-increasing pace.

The workforce is also changing. With the U.S. workforce expected to grow to approximately 166 million by the year 2018, it will become older and more racially diverse (BLS, 2008a). In 2005 there were 131.6 million employed workers (BLS, 2007). In 2008, the workforce was comprised of 48% women, 11% blacks, and 14% Hispanics (BLS, 2008b). These changes will continue to present new challenges to protecting worker safety and health.

The demographic trends in the U.S. workforce describe a changing population aggregate that has implications for the prevention services targeted to that group. Major changes in the working population are reflected in the increasing numbers of women, older individuals, and those with chronic illnesses who are part of the workforce. Because of changes in the economy, extension of life span, legislation, and society’s acceptance of working women, the proportion of the employed population that these three groups represent will probably continue to grow.

For example, in the late 1990s while nearly 60% of all women were employed, women were predicted to account for 67% of the increase in the labor force in the twenty-first century (BLS, 2005b). These workers tended to be married, with children and aging parents for whom they were responsible. This aggregate of workers presents new issues for individual and family health promotion, such as child care and elder care, that can be addressed in the work environment. In 1990 more than half of the female labor force was concentrated in three areas: administrative support/clerical (26%), service (14%), and professional specialty (14%). Twelve percent were employed in fields such as labor, transportation and moving, machine operation, precision products, crafts, farming, construction, forestry, and fishing. In the male labor force, nearly 20% worked in precision production, crafts, or repair occupations, 13% in executive positions, 11% in professional specialty occupations, and 10% in sales. Other trends shaping the profile of the workforce include more education and mobility. Increasing mismatches between skills of workers and types of employment were seen in the 1990s.

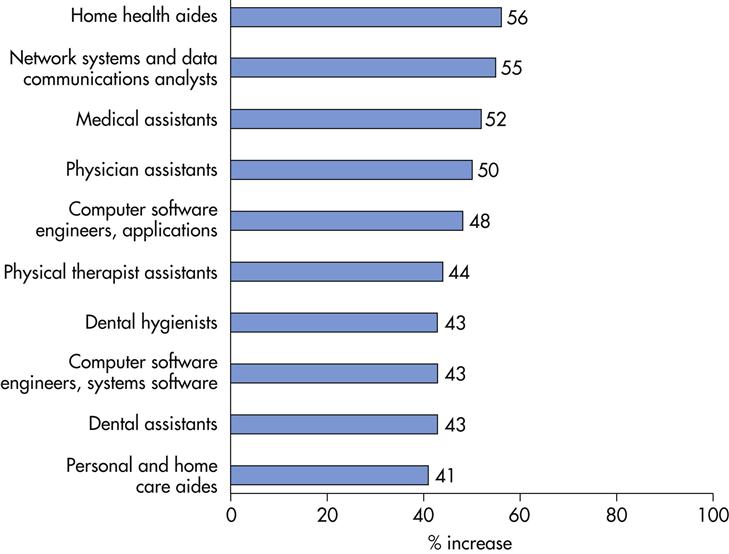

Future employment trends projected to 2014 are shown in Figure 43-1. Of the 20 fastest growing occupations in the economy, half are related to health care. Health care is experiencing rapid growth, due in large part to the aging of the baby-boom generation, which will require more medical care. In addition, some health care occupations will be in greater demand for other reasons. As health care costs continue to rise, work is increasingly being delegated to lower-paid workers in order to cut costs. For example, tasks that were previously performed by doctors, nurses, dentists, or other health care professionals increasingly are being performed by physician assistants, medical assistants, dental hygienists, and physical therapist aides. In addition, clients increasingly are seeking home care as an alternative to costly stays in hospitals or residential care facilities, causing a significant increase in demand for home health aides. Although not classified as health care workers, personal and home care aides are being affected by this demand for home care as well (Bartsch, 2009).

Characteristics of Work

There has been a dramatic shift in the types of jobs held by workers. Following the evolution from an agrarian economy to a manufacturing society and then to a highly technological workplace, the greatest proportion of paid employment was in the occupations of trade, transportation, and utilities with 25 million workers (BLS, 2008b). During the 1996 to 2000 period, service-providing industries accounted for virtually all of the job growth. Only construction added jobs in the goods-producing business sector, offsetting declines in manufacturing and mining. According to the BLS (2008b), jobs in construction, transportation, wholesale and retail trade, health care, and service-producing industries are expected to increase by 2018. (Table 43-1 shows occupations with the fastest growth.)

TABLE 43-1

OCCUPATIONS WITH THE FASTEST GROWTH

| OCCUPATIONS | PERCENT CHANGE | NUMBER OF NEW JOBS (IN THOUSANDS) | WAGES (MAY 2008 MEDIAN) | EDUCATION/TRAINING CATEGORY |

| Biomedical engineers | 72 | 11.6 | $ 77,400 | Bachelor’s degree |

| Network systems and data communications analysts | 53 | 155.8 | 71,100 | Bachelor’s degree |

| Home health aides | 50 | 460.9 | 20,460 | Short-term on-the-job training |

| Personal and home care aides | 46 | 375.8 | 19,180 | Short-term on-the-job training |

| Financial examiners | 41 | 11.1 | 70,930 | Bachelor’s degree |

| Medical scientists, except epidemiologists | 40 | 44.2 | 72,590 | Doctoral degree |

| Physician assistants | 39 | 29.2 | 81,230 | Master’s degree |

| Skin care specialists | 38 | 14.7 | 28,730 | Post-secondary vocational award |

| Biochemists and biophysicists | 37 | 8.7 | 82,840 | Doctoral degree |

| Athletic trainers | 37 | 6.0 | 39,640 | Bachelor’s degree |

| Physical therapist aides | 36 | 16.7 | 23,760 | Short-term on-the-job training |

| Dental hygienists | 36 | 62.9 | 66,570 | Associate’s degree |

| Veterinary technologists and technicians | 36 | 28.5 | 28,900 | Associate’s degree |

| Dental assistants | 36 | 105.6 | 32,380 | Moderate-term on-the-job training |

| Computer software engineers, applications | 34 | 175.1 | 85,430 | Bachelor’s degree |

| Medical assistants | 34 | 163.9 | 28,300 | Moderate-term on-the-job training |

| Physical therapist assistants | 33 | 21.2 | 46,140 | Associate’s degree |

| Veterinarians | 33 | 19.7 | 79,050 | First professional degree |

| Self-enrichment education teachers | 32 | 81.3 | 35,720 | Work experience in a related occupation |

| Compliance officers, except agriculture, construction, health and safety, and transportation | 31 | 80.8 | 48,890 | Long-term on-the-job training |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree