The Nurse in Home Health and Hospice

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Compare different practice models for home-based services.

2. Summarize the basic roles and responsibilities of home health and hospice nurses.

4. Describe the three components of the Omaha System.

Key Terms

accreditation, p. 904

benchmarking, p. 904

client outcomes, p. 898

documentation, p. 897

electronic health records, p. 896

evidence-based practice, p. 892

family caregiving, p. 891

home health care, p. 890

home health nursing, p. 890

hospice and palliative care, p. 890

hospice care, p. 892

information management, p. 897

interoperability, p. 908

interprofessional collaboration, p. 890

meaningful use, p. 908

medical home, p. 894

Medicare-certified, p. 894

nursing practice, p. 897

nursing process, p. 896

Omaha System, p. 896

Omaha System Intervention Scheme, p. 897

Omaha System Problem Classification Scheme, p. 897

Omaha System Problem Rating Scale for Outcomes, p. 898

Outcome-Based Quality Improvement, p. 904

Outcome and Assessment Information Set, p. 902

palliative care, p. 892

practice settings, p. 893

regulations, p. 895

skilled nursing care, p. 900

skilled nursing services, p. 895

telehealth, p. 908

transitional care, p. 892

— See Glossary for definitions

Karen S. Martin, RN, MSN, FAAN

Karen S. Martin, RN, MSN, FAAN

Karen S. Martin is a health care consultant who has been in private practice since 1993. She works with service and educational settings nationally and internationally as they evaluate and improve their practice, documentation, and information management systems to meet quality and data exchange, as well as interoperability standards, for electronic health records. She is also a consultant to software developers. Karen has been employed as a staff nurse, director of a combined home care/public health agency, and, from 1978 to 1993, the Director of Research of the Visiting Nurse Association of Omaha, Nebraska, where she was the principal investigator of Omaha System research.

Kathryn H. Bowles, RN, PhD, FAAN

Kathryn H. Bowles, RN, PhD, FAAN

Kathryn H. Bowles is an Associate Professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing and the New Courtland Center for Transitions and Health. For several years, Dr. Bowles was the Director of Nursing Research at the Visiting Nurse Association of Greater Philadelphia and is currently the Beatrice Renfield Visiting Scholar at the Visiting Nurse Service of New York, with a focus on bringing evidence-based practice to home care. Her program of research focuses on improving care of the elderly using information technology such as decision support for hospital discharge planning and referral decision making, as well as testing telehealth technologies in community-based settings.

Home health and hospice nurses are rapidly expanding practice specialties. For the purposes of this chapter, home health and hospice refer to a wide variety of holistic services provided to clients of all ages in their residences and other non-institutional settings. Assessment, planning, intervention, and evaluation are the focus of the services. Note that hospice care can be provided in acute care facilities, and many home health agencies offer these services in addition to home visits. Numerous references in this chapter describe home health research, economics, and client personal preference, suggesting that the home is the optimal location for diverse health and nursing services (Olds et al, 1997; Kitzman et al, 2000; Schumacher et al, 2006; Buhler-Wilkerson, 2007; Mader et al, 2008; NAHC, 2008; Beales and Edes, 2009; Homer et al, 2008; HAA, 2009; Ferrante et al, 2010; Naylor and Van Cleave, 2010). Client residences include houses, apartments, trailers, boarding and care homes, hospice houses, assisted living facilities, shelters, and cars. Home health and hospice services are provided by formal caregivers who include nurses, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, home health aides, chaplains, physicians, and others. Because of the nature of home health and hospice practice, a team approach and interprofessional collaboration are required. The specific disciplines who are involved vary with the program, the intensity of the client and family’s needs, and the location of the program and home.

Access to other health care professionals, resources, and equipment is very different when home and institutional care settings are compared. Many nurses find home health and hospice practice very rewarding because they observe the impact of their services and practice with a high degree of autonomy. Nurses who make home visits need to have good organizational, communication, and documentation skills. Competence, integrity, adaptability, and creativity are essential characteristics. Nurses need to anticipate danger from people and circumstances in the physical environment to be savvy about their own safety as well as the safety of their clients (Humphrey and Milone-Nuzzo, 2010).

Home health care is a broad concept and approach to services. It includes a focus on primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention; the primary focus can involve aggregates, similar to other population-focused nurses. (See the Levels of Prevention box.) Home health nursing is “a specialized area of nursing practice, rooted in community health nursing, that delivers care in the residence of the client” (ANA, 2007, p 54). Home health nurses include generalist nurses, public health nurses, clinical nurse specialists, and nurse practitioners. They and their interprofessional team members provide diverse services to target populations such as new parents, frail elders, and clients who have injuries, surgery, disabilities, and acute or chronic health problems.

Hospice and palliative care are equally broad concepts and approaches to care. Hospice and palliative nursing are specialized areas of practice designed to “provide evidence-based physical, emotional, psychosocial, and spiritual or existential care to individuals and families experiencing life-limiting, progressive illness” (HPNA & ANA, 2007, p 1). Palliative services can be initiated whether or not cure is possible and can be considered a continuum of care. In contrast, hospice involves supportive services when a life-limiting illness does not respond to curative treatment, is the end-of-life portion of the continuum, and is regulated as a 6-month time period by Medicare (Viola et al, 2009; Perry and Parente, 2010). Advanced practice hospice and palliative nursing are emerging roles. Nurses work closely with members of other disciplines to provide comprehensive interprofessional care; volunteers are important team members.

When entering a client’s home, the nurse is a guest and needs to earn the trust of the family and establish a partnership with the client and family (Figure 41-1). It is essential that clients and families are involved in making decisions for home-based services to be efficient and effective. Family is defined by the individual client and includes any caregiver or significant other who assists the client with care at home. Family caregiving involves transportation, helping clients meet their basic needs, and providing care such as personal hygiene, meal preparation, medication administration, and simple as well as complex treatments. Today’s clients and family caregivers provide many aspects of care in the home that were previously provided in hospitals or in home by professional care givers. Care can be confusing, challenging, stressful, and frightening for family caregivers (Schumacher et al, 2006; Buhler-Wilkerson, 2007; Altilio et al, 2008; Honea et al, 2008; Gorski, 2010). Clients need to be monitored regularly, and some require 24-hour care. It is likely that family members are grieving when clients receive end-of-life care. Nurses need to identify support services that enable family caregivers to provide care while maintaining their own physical and emotional health status.

Evolution of Home Health and Hospice

Home health care provided by formal caregivers in the United States originated in the nineteenth century, and was based on the district nursing model developed by William Rathbone in England. In many communities, the initial programs evolved into visiting nurse associations. The movement expanded rapidly in the United States, resulting in the formation of 71 agencies prior to 1900, and 600 organizations by 1909. Additional historical details are described in Chapter 2 and other publications (Buhler-Wilkerson, 2002; Donahue, 2011).

In 1893, Lillian Wald and Mary Brewster established the Henry Street Settlement House in New York City and developed a comprehensive program to address health and illness, poverty, education, shelter, and other basic needs. Nurses such as Lillian Wald, Mary Brewster, and Lavinia Dock were social activists who organized health care services, convinced community leaders to support their programs, provided national leadership, and published extensively. One of Lillian Wald’s most impressive innovations was to convince the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to include home visits as a benefit in the early 1900s and to examine the cost effectiveness of care. That partnership continued until 1952 (Buhler-Wilkerson, 2002; Donahue, 2011).

After World War I, the problems related to immigration and infectious diseases decreased. Simultaneously, the heightened public and professional interest in maternal-child health led to an increase in the number of public health departments and the nurses they employed (Buhler-Wilkerson, 2002; Donahue, 2011).

Home health services were included as a major benefit when Medicare legislation was passed in 1965, and resulted in significant changes nationally. The benefit was designed to provide intermittent, shorter visits with temporary lengths of stay to persons age 65 and older; health promotion and long-term care were not reimbursed. When a client was admitted to service, the home health agency was required to develop a plan of care and obtain the signature of a physician. During the next 30 years, the number of Medicare-certified agencies grew rapidly as a result of the aging population and prospective payment legislation that decreased the length of hospital stays. This trend changed when the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 was enacted; the legislation was designed to reduce federal home health reimbursement by initiating a per-beneficiary (or client) visit limit. The Act prompted the closure of more than 30% of the country’s Medicare-certified home health agencies and a dramatic decline in the number of clients served (Schlenker et al, 2005; NAHC, 2008).

Hospice care was introduced in the United States in the 1970s by Florence Wald, often referred to as the mother of the hospice movement. She began her career as a staff nurse at the Visiting Nurse Service of New York and became Dean of the Yale University School of Nursing. Before establishing Connecticut Hospice in 1974, Dr. Wald collaborated with Dame Cicely Saunders, a British nurse, physician, and social worker who founded St. Christopher’s Hospice in England in 1967 (Zerwekh, 2006; Gazelle, 2007). During the same era, Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a physician, published On Death and Dying (1969), a book that was widely read by the public and health care professionals. Dr. Ross described the inhumanity of a death-denying society such as the United States, and the need to provide sensitive end-of-life care and involve clients in choices. The concept of hospice grew from a commitment to provide compassionate and dignified care to people in the comfort of their homes, and an emphasis on the quality of life (Zerwekh, 2006; Gazelle, 2007; Malloy et al, 2008; Perry and Parente, 2010; Sanders et al, 2010).

In 1987, the first comprehensive, integrated palliative care program was established at the Cleveland Clinic; it expanded from an inpatient unit to a comprehensive program that included a hospice affiliation. In 1999, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded the Center to Advance Palliative Care to stimulate the development of high-quality palliative care programs in hospitals and other health care settings. Both home-based and inpatient hospice and palliative care models share a focus on comfort, pain relief, and mitigation of other distressing symptoms (Altilio et al, 2008; Viola et al, 2009; Perry and Parente, 2010; Sanders et al, 2010).

Medicaid reimbursement for hospice care began in 1980 and Medicare in 1983; reimbursement determines many aspects of the programs. Physicians need to indicate that clients have 6 months or less to live, and clients acknowledge that they have a terminal prognosis and select care that is comfortable, not life-extending. Because the time of death is difficult to predict and many people in this country are reluctant to acknowledge a terminal prognosis, hospice care often begins late in the disease process (Zerwekh, 2006; HAA, 2009; Viola et al, 2009; Perry and Parente, 2010).

Description of Practice Models

Population-focused home care, transitional care, home-based primary care, home health, and hospice are models in current use. All involve interprofessional collaboration as well as interest in best practices and evidence-based practice. Best practices suggest using the best possible evidence from a variety of sources including research, experience, and expert practitioners; evidence-based practice suggests increased emphasis on programs of research that demonstrated consistently good outcomes. The models vary regarding the size and extent of participation, focus of the services, target population, research, political involvement, and funding. With each model, nurses have essential roles in the provision of care, documentation of services, program development and management, outcome and effectiveness analysis, and public education.

Population-Focused Home Care

Using an evidence-based and data-driven approach to population-focused home care, certain models of care delivery have produced superior outcomes. These models usually include structured approaches to regular visits with assessment protocols, focused health education, counseling, and health-related support and coaching. Examples of population-focused home care are described in the following paragraphs.

A group of researchers conducted studies involving clients who had psychiatric illnesses and lived in various community settings. During one interprofessional study, psychiatric nurses made home visits to elders who lived in public housing, had psychiatric symptoms, and were referred by building personnel (Rabins et al, 2000). The nurses conducted comprehensive psychiatric assessments; provided counseling, coaching, medication monitoring, and referrals; and coordinated care with social workers and physicians. Clients’ psychiatric symptoms were reduced. The findings of another study indicated that clients who had dementia benefited when hospice care was provided, as did their family caregivers (Bekelman et al, 2005).

In Australia, a nurse and a pharmacist made home visits to older adults with diagnoses of atrial fibrillation and heart failure (Inglis et al, 2004). They conducted comprehensive health and medication assessments, provided health education, and made follow-up referrals. The nurse maintained telephone contact with clients for 6 months and provided care coordination. Clients in the experimental home visiting group had fewer hospital readmissions and shorter hospitalizations than those in a control group.

In Taiwan, public health and home health nurses participated in an extensive, interprofessional community-oriented program of research using home and clinic visits and telephone calls. Huang et al (2004) reported on the effectiveness of a 6-week home nursing program with elderly Chinese diabetic clients who lived alone. After weekly visits including structured education and monitoring, elders improved their levels of fasting blood glucose, post-meal blood glucose, and hemoglobin A1c. The researchers (Huang, 2005; Hsueh et al, 2010) also demonstrated successful outcomes when nurses have provided smoking cessation education and encouragement to long-term smokers. The Nurse-Family Partnership was initiated in 1977 by a researcher, David Olds, and a nurse, Harriet Kitzman; it is probably the best known and well-funded nurse home visit program in the United States (Olds et al, 1997; Kitzman et al, 2000). The Partnership involves nurses who provide structured education and case management during regularly scheduled home visits to pregnant women; visits continue until the children’s second birthday. Recipients of care have been ethnically diverse, low-income, first-time mothers and their families who lived in New York, Tennessee, and Colorado. Longitudinal, randomized controlled trials documented numerous lifelong improvements in health outcomes that were statistically significant and economically sound. Mothers had fewer children, were more likely to become employed, and were less likely to enter the criminal justice system; children were less likely to be abused; and both mothers and children demonstrated improved health and development. The researchers estimate that nurses visit more than 30,000 families in nearly 40 states; federal and private funding continues to increase as the program maintains successful outcomes and grows (Olds et al, 1997; Kitzman et al, 2000; Donelan-McCall et al, 2009).

The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) began in 1972, and is a managed care model of integrated health and personal care services for non-institutionalized individuals aged 55 and older who meet frailty criteria (Dobell and Newcomer, 2008). Interprofessional care is provided in adult day-care centers with home-based assessments and supportive services also provided as needed. Home health care and hospice can be services offered through this model. Because of the model’s success, it is now included in Medicare and Medicaid capitation plans. As of 2009, 72 PACE programs operated in 30 states (National PACE Association, 2010).

Transitional Care

As a result of a fragmented health care system, increasing complexity of client care, and rising costs, transitional care has gained much needed attention. Transitional care is defined as “a set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of health care as clients transfer between different locations and different levels of care in the same location” (Coleman and Berenson, 2004, p 1). Challenges to quality care originate from a lack of depth, accuracy, and timeliness of information received from the referring site; the need for complex medication reconciliation; and difficulties with communication and coordination among community-based providers.

Transitional care programs that involve home health have emerged as low- and high-intensity interventions that include, but vary from, traditional home care interventions. Low-intensity interventions include coaching, telephone follow-up, and specific disease management programs (Boling, 2009). For example, a program by Coleman and colleagues (2006) proposes an intervention that emphasizes medication self management, use of a client-centered health record, arranged physician follow-up, and client education about warning signs, symptoms, and how to respond to them. The intervention includes a home visit and at least three telephone calls made by a nurse or trained provider after a transition.

High-intensity transitional care programs are designed for populations who have complex or high-risk health problems. An example is the Transitional Care Model where advanced practice nurses perform transitional care from hospital to home providing in-hospital visits and discharge planning followed with home visits, primary care office visits, and telephone follow-up for 1 to 3 months after discharge (Brooten et al, 2001; Naylor, 2004; Naylor and Van Cleave, 2010). Examples of high-risk groups for whom the Transitional Care Model has been tested in numerous studies include women with high-risk pregnancies, adults with cognitive impairments, older adults with common medical and surgical conditions, and older adults with heart failure (Brooten et al, 2001; Naylor, 2004; Naylor and Van Cleave, 2010). The research model is currently implemented in practice settings in collaboration with major insurance companies and home care agencies (Naylor and Van Cleave, 2010).

Outcomes achieved with the Transitional Care Model consistently show cost savings and improvements in clinical and quality outcomes for clients receiving the intervention compared with usual care. The most common outcome across all populations is a consistent reduction in readmissions to a hospital. The Transitional Care Model strategies emphasize screening in acute care for high-risk clients; engaging the elder/caregiver in designing personalized goals and the plan of care; managing symptoms; educating and promoting self-management; and collaborating with the multidisciplinary team members to assure continuity and collaboration.

Home-Based Primary Care

The goal of home-based primary care is to offer clients an alternative to receiving services in a primary care clinic, community center, or physician’s office. These clients have functional or other health problems that make the trip from their homes to other care sites very difficult.

The Veterans Affairs Administration Hospital-Based Home Care Program targets individuals who have complex chronic disabling diseases with the goal of maximizing the independence of the client and reducing preventable emergency room visits and hospitalizations (Beales and Edes, 2009). An interprofessional team provides comprehensive longitudinal primary care that incorporates telehealth and electronic health records (EHRs). Nurses serve as case managers, continually evaluate clients’ needs, and deliver care. Approximately three fourths of Veterans Affairs facilities offer the home care program. The program has produced positive outcomes (Mader et al, 2008; Beales and Edes, 2009; Chang et al, 2009).

In 1967, the American Academy of Pediatrics originated the concept of medical home in an attempt to establish centralized, accessible health care records for medically complex, chronically ill children (Friedberg et al, 2009; Homer et al, 2008). Although there are distinct variations of medical home, the models typically include superb access to care; client engagement in care; EHRs that may be client controlled; care coordination; integrated, comprehensive care; ongoing, routine client feedback; and publicly available information about practices (Davis and Stremikis, 2010; Ferrante et al, 2010). More recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and politicians supported medical home as a model to decrease costs and incorporated the concept into health care reform. Nurse practitioners are especially interested in policy implications and participating as leaders in this movement (Graham, 2010).

Home Health

Staff members of home health agencies provide care at home and help clients and their families achieve improved health and independence in a safe environment. According to CMS (2008) and NAHC (2008), approximately 7.6 million clients received Medicare-certified home health services in 2007. Persons who were 65 years and older accounted for more than 85% of all home health clients. Recipients of home health services had diverse needs, but circulatory disease was the most common diagnosis, followed by neoplasms and endocrine diseases, especially diabetes. It was estimated that 9284 Medicare-certified home health agencies employed up to 17,000 staff members. The size of individual agencies varied from those that employ a few nurses to the Visiting Nurse Service of New York with its 2500 nurses and more than 12,000 staff members (VNSNY, 2010). Annual national expenditures for home health care in 2007 and 2008 were approximately $57 to $64 billion. As the largest payer, Medicare accounted for 37% of total home health reimbursement. Home health payments represented 3.3% of the total Medicare reimbursement while hospitals represented approximately 35%. In addition to Medicare, state and local governments accounted for 19.9% of home health reimbursement, Medicaid for 19%, private insurance for 12%, out-of-pocket or private pay 10%, and other sources 3% (CMS, 2008; NAHC, 2008).

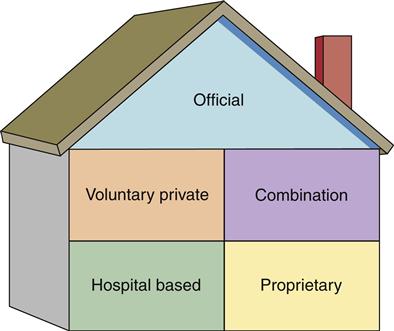

Home health agencies can be divided into five general categories with a description of each to follow:

• Official/public: approximately 13% of total home health agencies

• Private and voluntary: approximately 12% of total home health agencies

• Combination: approximately 0.5% of total home health agencies

• Hospital based: approximately 19% of total home health agencies

• Proprietary: approximately 56% of total home health agencies (Figure 41-2)

Official or public agencies receive tax revenue and are operated by state, county, city, or other local government units, such as health departments. Typically, official agencies also offer well-child clinics, immunizations, health education programs, and home visits for preventive health care.

Voluntary and private agencies are non-profit home health agencies and usually receive some funds from United Way, donations, and endowments. Currently, there are about the same number of voluntary and private agencies.

Combination agencies have characteristics of both governmental and voluntary agencies. The number of combination agencies continues to decrease although some are large agencies.

Hospital-based agencies grew rapidly during the 1970s and 1980s when the advent of diagnostic-related groups led to earlier hospital discharges. Some hospitals and their home health agencies are separating because of recent changes in Medicare reimbursement.

Proprietary agencies are free-standing, for-profit agencies that are required to pay taxes. Many are part of large chains. Proprietary agencies now dominate the industry.

In addition to Medicare-certified home health agencies, there are other agencies that are not certified. These are often private agencies, governed by individual owners or corporations that offer private duty, home health aide, and homemaker services.

Although the size, administrative, organizational, and board structures of Medicare-certified agencies differ, they must meet ever-changing licensure, certification, and accreditation regulations established by national and state groups (Buhler-Wilkerson, 2007; NAHC, 2008; Fazzi et al, 2010). The primary source of those regulations is CMS (2009). Because the conditions are lengthy and complex, many agencies employ a nurse to become an expert and ensure that the agency is in compliance. To be Medicare-certified, key criteria identified in the Conditions of Participation are: (a) the client must be home-bound, (b) services must be intermittent and include a skilled service provided by a nurse, physical therapist, or speech and language pathologist, (c) a plan of care must be initiated and followed, and (d) Medicare forms, physician orders, and client records must be completed on a timely basis. Skilled nursing services is the Medicare term that describes the duties of the registered nurse, and refers to the requirement of nursing judgment. Those services involve assessment, teaching, and selected procedures; using Omaha System terms, they may also be categorized as Teaching, Guidance, and Counseling; Treatments and Procedures; Case Management; and Surveillance (Martin, 2005).

Hospice

Slightly more than 1 million clients received Medicare-certified hospice services in 2007 with an average stay of 71 days. The average length of stay is rising as home health nurses and others provide information about end-of-life hospice care to clients and families, and hospice becomes more widely accepted by the public. Initially, cancer was the primary diagnosis of most clients; currently, cancer is the diagnosis of about one third of hospice clients and various neurological, cardiac, and other end-stage diseases comprise two thirds of the diagnoses (Zerwekh, 2006; NAHC, 2008; HAA, 2009; Perry and Parente, 2010).

Medicare, Medicaid, managed care, private insurance, and private donations fund most hospice services. The number of Medicare-certified hospices grew from 31 in 1984 to more than 3000 in 2009. Hospice services account for approximately 2.5% of the total Medicare budget, just less than home health services. Services are provided based on Medicare criteria. After the client acknowledges a terminal prognosis and selects comforting care rather than life-extending care, hospice organizations coordinate services in partnership with the client and family and provide financial case management. The four types of care and the percentage documented in 2005 were: (1) routine home care with intermittent visits, 96.5%, (2) continuous home care when condition is acute and death is near, 1.1%, (3) general inpatient/hospital care for symptom relief, 2.2%, and (4) respite care in a nursing home of no more than 5 days at a time to relieve family members: 0.2% (NAHC, 2008; HAA, 2009).

Medicare-certified hospice providers can be divided into the following four general categories:

• Home health agencies: approximately 18% of total hospice providers

• Hospital-based facilities: approximately 16% of total hospice providers

• Skilled nursing facilities: approximately 0.6% of total hospice providers

• Free-standing facilities: approximately 65% of total hospice providers

Hospice programs are usually operated and staffed as independent entities or corporations even when they are part of a larger organization because of the specialized nature of the practice and complex regulations. The focus of hospice care is comfort, peace, and a sense of dignity at a very difficult time. Comprehensive services emphasize continuity of care. According to Zerwekh (2006), hospice addresses four foci: (1) attention to the body, mind, and spirit, (2) death is not a taboo topic, (3) health care technology should be used with discretion, and (4) clients have a right to truthful discussion and participation in treatment decisions.

The client’s family and friends are essential hospice team members who are involved in symptom and medication management, personal care, and the use of supplies. Death produces intense emotions even when family members have prepared for it. Bereavement services involve attending the funeral or other services for the deceased client, and contact at anniversaries of death, holidays, and the client’s birthday for 13 months after the client’s death. Hospice organizations usually offer support group opportunities for families or refer them to support groups in the area (Altilio et al, 2008; Baker et al, 2008; Malloy et al, 2008).

The interprofessional hospice team includes nurses, physicians, social workers, therapists, chaplains, counselors, aides, pharmacists, and volunteers. In 2008, there were approximately 95,000 employees and 50,000 volunteers; nurses, aides, and social workers were the largest groups of employees (NAHC, 2008). There were more than 10,000 hospice-credentialed nurses and 271 certified advanced practice nurses in palliative care; the latter group included clinical specialists and nurse practitioners (HPNA/ANA, 2007). Working with clients who are dying involves unique emotional stress; hospice programs address the team’s well-being as well as that of the clients and families (Hinds et al, 2005; Zerwekh, 2006; HPNA/ANA, 2007; Baker et al, 2008; HAA, 2009; Viola et al, 2009).

Home Care of Dying Children

“The death of a child alters the life and health of others immediately and for the rest of their lives” (Hinds et al, 2005, p S70). The needs of dying children and their families are unique because of the degree of emotional impact, and because the young are not expected to die or precede the death of their parents. It is essential that nurses understand the child’s physical, cognitive, psychosocial, and spiritual development and family dynamics, cultural heritage, and spiritual beliefs in order to provide appropriate pain management, assist the child and family to communicate with each other, advocate for their needs in the community, and provide case management and continuity of care (Baker et al, 2008; Hinds et al, 2005).

Bereavement programs as described for hospice programs are especially important for families who have lost a child. Parents, grandparents, and siblings can participate in a variety of support groups offered by the hospice program or other bereavement organizations.

Scope and Standards of Practice

Nursing is a theory and practice-based profession that incorporates art and science. Examples of nursing, family, and systems theories are mentioned and summarized in other chapters of this book. Chapter 15 addresses evidence-based practice; the concept is addressed frequently in this chapter and two examples are included. Several chapters of this book describe the Quad Council’s (2003) eight domains of practice; those domains are linked to information in this chapter in the Linking Content to Practice box.

The nursing process is the theoretical framework used by the ANA, which notes that the nursing process is the essential methodology by which client goals are identified and achieved. Their scope and standards publications, including those for Home Health Nursing and Hospice and Palliative Nursing, are organized according to the nursing process and contain two sections: the Standards of Care and the Standards of Professional Performance (ANA, 2007; HPNA/ANA, 2007). Both include the six steps of the nursing process: assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation; the steps are linked to standards and more specific measurement criteria that are stated in behavioral objectives. The standards address quality of care, performance appraisal, education, collegiality, ethics, collaboration, research, and resource use.

Omaha System

According to Clark and Lang (1992), “If we cannot name it, we cannot control it, finance it, teach it, research it or put it into public policy” (p 27). The Omaha System was initially developed to operationalize the nursing process and provide a practical, easily understood, computer-compatible guide for daily use in community settings. It is the only ANA-recognized terminology developed inductively by and for nurses who practice in the community. From the initial home health and hospice focus, adoption has expanded so that current users and user sites represent the continuum of care. Approximately 9000 multi-professional practitioners, educators, and researchers use Omaha System point-of-care electronic health records (EHRs) in the United States and other countries, and 2000 more use paper-and-pen records. EHRs are longitudinal collections of clinical and demographic client-specific data that are stored in a computer-readable format. Details about Omaha System application, users, case studies, inclusion in reference terminologies, research, best practices/evidence-based practice, and listserv are described in publications and on the website (Martin, 2005; Omaha System, 2010, Martin et al, 2011).

Description of the Omaha System

As early as 1970, the nurses, other staff, and administrators of the Visiting Nurse Association (VNA) of Omaha, Nebraska, began addressing nursing practice, documentation, and information management concerns. At that time, practitioners were not using computers, and there was no systematic nomenclature or classification of client problems and concerns, interventions, or client outcomes to quantify clinical data and integrate with a problem-oriented record system. These realities provided the incentive for initiating research and involving community test sites throughout the country. Between 1975 and 1993, the VNA of Omaha staff conducted four extensive, federally funded development and refinement research studies that established reliability, validity, and usability of the Omaha System. Avedis Donabedian, the developer of the structure, process, and outcome approach to evaluation, was a valuable consultant (Donabedian, 1966; Martin, 2005). The result of the research was the Problem Classification Scheme, the Intervention Scheme, and the Problem Rating Scale for Outcomes. These three components of the Omaha System were designed to be used together, be comprehensive, relatively simple, hierarchical, multi-dimensional, and computer compatible. The Omaha System has existed in the public domain since the initial research in 1975, and therefore is not held under copyright (Martin, 2005; Omaha System, 2010; Martin et al, 2011).

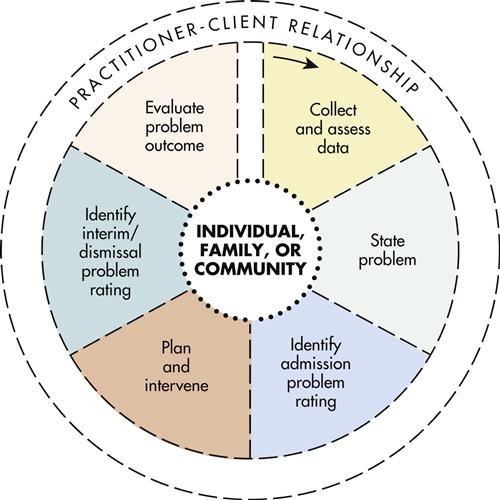

As depicted in Figure 41-3, the Omaha System conceptual model is based on the dynamic, interactive nature of the nursing or problem-solving process, the practitioner–client relationship, and concepts of diagnostic reasoning, clinical judgment, and quality improvement. The client as an individual, a family, or a community appears at the center of the model; this location suggests the many ways the Omaha System can be used and the essential partnership between clients and practitioners.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree