Chapter 3 The Initial Contact and Therapeutic Communication

The two most important goals of the first session are to initiate a therapeutic alliance and to assess safety. Both are foundational to the treatment hierarchy described in Chapter 1, and they provide the basis for the psychotherapeutic process. The psychobiologic underpinnings of the therapeutic alliance are discussed in Chapter 2 and this chapter discusses strategies for developing the therapeutic alliance. The therapeutic alliance cultivates a healing environment for emotional safety and allows the patient to continue psychotherapy and to benefit from treatment. Safety issues include assessment of how safe the patient is from him/herself and from others. The first contact with the patient is described along with issues germane to the first session, such as making practical arrangements, setting goals, how to end a session, and what records to keep. The chapter culminates with a review of therapeutic communication.

Developing a Therapeutic Alliance

The therapeutic alliance is initiated in the first contact with the patient, and the first several sessions are crucial for laying the foundation for the therapist’s connection with the patient. A meta-analytic review of research studies found that the therapeutic alliance is itself therapeutic and essential for the successful outcome of treatment no matter what model of therapy is used (Castonguay et al., 1996; Horvath & Symonds, 1991; Krupnick et al., 1996; Martin et al., 2000).

A challenge for the therapist is to engage the patient so s/he will continue. A meta-analysis of 126 studies shows that the dropout rate after the initial session is quite high at 50% (Wierzbicki & Pekarid, 1993). The therapeutic alliance is necessary to help the patient, and the first session lays the foundation for the alliance, enabling the patient to continue treatment.

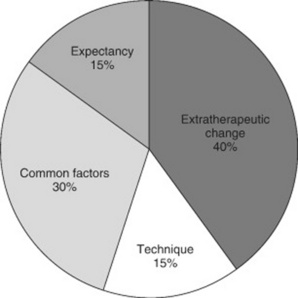

Psychotherapy outcome research confirms the importance of the therapeutic alliance based on decades of research and an exhaustive review of these studies (Lambert & Barley, 2002). The percent of improvement in psychotherapy patients is a function of various therapeutic factors and includes expectancy (i.e., the placebo effect), technique, extratherapeutic change (e.g., friends, family, self-help, group participation, clergy), and common factors (e.g., therapist empathy, warmth, acceptance, encouragement of risk taking, confidentiality of relationship, and the therapeutic alliance) (Figure 3-1). In other words, what the therapist does is less important than how the therapist does it. The process is more important than technique, because the latter only accounts for 15% of change in psychotherapy outcome.

Figure 3-1 Percent of improvement in psychotherapy.

(From Lambert M. J., & Barley, D. E. [2002]. Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. In J. Norcross [Ed.], Psychotherapy relationships that work [pp. 17–32]. New York: Oxford University Press.)

The ideal is to develop a basic level of trust and a shared agenda with the patient, which includes the collaborative goals of therapy. Three elements of the therapeutic alliance that most theorists agree with are the collaborative nature of the relationship, the affective bond between the patient and therapist, and the agreement between the therapist and patient on the goals of treatment (Martin et al., 2000). Competencies that reflect the therapist’s ability to develop a therapeutic alliance include the ability to establish rapport, to recognize the different forms of a therapeutic alliance, to enable the patient to actively participate in the process, to establish a treatment focus, to provide a healing environment, and to recognize and attempt to repair the alliance if needed. Cultivating the therapeutic alliance is an ongoing process throughout the therapy.

Horvath elaborates on the therapeutic alliance:

Developing the alliance takes precedence over technical interventions in the beginning of therapy. Therapists need to be sensitive to the risk that their own estimate of the status of the relationship, particularly in the opening phases of therapeutic work, can be at odds with the patients and such misjudgment may have costly consequences. Thus it seems prudent to actively solicit from patients their perspective on various aspects of the alliance and to negotiate flexibly the goals of treatment and even the content of therapy to secure their active collaboration and engagement. Particularly close attention is warranted in the early phases of work with the patient who is diagnosed with relational problems … these patients not only find it difficult to engage in an intimate relationship such as the one between therapist and patient, but they also are likely to solicit negative or rejecting therapist responses. The value of an open, flexible stance as opposed to relational control or rigid expectations on the part of the therapist is a consistent theme across much of the literature. The therapists who can complement the patient’s relational style and are able to demonstrate a capacity to collaborate (e.g., adopt the patient’s ideas, “leapfrog” using the patient’s ideas or expressions) seem to have a better chance of guiding good alliances. On the other hand, therapists who were seen by patients as rigid or “cold” were rated as less effective and had poorer alliances. Negative or rejecting transactions seem to have a particularly insidious impact on the alliance, and there are preliminary indications that such hostile therapist responses may be related to the therapist’s own negative introject (Horvath, 2001, pp. 369-370).

Although numerous tools are available to measure the alliance (Martin et al., 2000), most therapists test the waters of the therapeutic alliance without the use of elaborate tools. One way is to ask the patient at the end of the first session: “How do you feel about working with me?” or “How did you feel about talking to me?” or “How did you feel about coming here today?” Alternatively, the therapist can question the patient at the beginning of the next session: “How did you feel after the last session?” Patients may respond positively, or they may say something negative, such as “My last therapist always was very involved, and I’m not sure you will be.” It is important to explore all negative feelings that the person brings up. Often, novice psychotherapists are hesitant to open up any suggestion of negative feelings with the patient for fear that the person will be more likely to leave treatment. The exact opposite is true; exploring the person’s negative feelings makes it much more likely that the person will stay in treatment.

What is most important for the beginning psychotherapist is learning how to develop the therapeutic alliance. Strategies for initiating and maintaining the therapeutic alliance include asking detailed questions about the patient’s main concern, validating affect, explaining the therapy process as it unfolds, listening empathically without minimizing or offering “fix it” statements, reminding the person that the two of you are working together toward a common goal, and pointing out the person’s strengths (Bender & Messer, 2003). Matching the therapist’s style to the patient’s needs (i.e., the therapist’s ability to be an “authentic chameleon”) facilitates the alliance (Lazarus, 1993). This requires the therapist to have facility in a range of techniques and a flexible repertoire of relationship styles to suit different patients’ needs and expectations.

For some patients, physical safety is an issue, whether real or imagined. For the psychotic patient, fears of fragmentation and annihilation may be the norm (Atwood et al., 2002). Even though psychotic patients may be compliant, it does not mean that they trust the therapist; they may adhere only out of fear of retribution if they do not. Clinicians who work with psychotic patients use various strategies to reduce the overwhelming anxiety experienced by the patient. Strategies include sitting farther away from the patient than usual, leaving the door open, taking as few notes as possible, giving information, communicating with emotional honesty and judicious self-disclosure, education, applying normalization, asking the person what would make him/her feel safe, assuming a more authoritative role, using simple communications, and creating opportunities for the person to demonstrate personal competency.

Assessing Safety

Assessing safety is of paramount importance in the initial contact. Every patient should be asked about suicidal or homicidal thoughts in the initial session. Although the patient with major depressive disorder usually is considered to be at particularly high risk, research has found that suicide is a risk for all persons with psychiatric disorders. Individuals with borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder have an equal or higher level of risk for suicide compared with those with major depression (De Hert & Peuskens, 2000; Jamison, 1999; Lonnqvist, 2000). The comorbidity of substance abuse is an important risk factor, along with social problems such as interpersonal violence, relationship difficulties, and social alienation.

Safety can be assessed with questionnaires such as the self-report Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which has a question about suicidality; interview questions; and a specific suicide assessment instrument, such as the SAD PERSONAS scale. The SAD PERSONAS scale is a semistructured interview that was developed by Patterson and colleagues (1983). The acronym SAD PERSONAS was created by using the first letters of 10 suicide risk factors. Box 3-1 shows this scale and scoring. A study conducted among third-year medical students showed that those who had received training in the SAD PERSONAS scale demonstrated greater ability to evaluate suicide risk and to make appropriate clinical interventions (Juhnke, 1994).

Box 3-1 Sad Personas Scale

Adapted from Juhnke, G. (1994). SAD PERSONAS scale review. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 27(1), 325-327.

However, Shea (1999) warns that the scale could fail as a predictive instrument. For example, a middle-aged woman who lacks 9 of the 11 factors but has postpartum psychosis is hearing voices that are convincing her that if she does not kill herself, demons will torture her daughter forever. Even though the woman scores only 1 point according to the SAD PERSONAS scale, her suicide risk is potentially very high. The strength of the scale is not as a precise risk predictor, but as a way of alerting the clinician that the patient may be at higher risk for suicide.

Research indicates that using both self-report and interview methods may be the best way to ensure accuracy, because some patients are thought to prefer the anonymity of a self-report form and the interviewer may get a negative response although the patient is suicidal (Yigletu et al., 2004). Several questions can be asked. “Do you ever experience hopelessness or suicidal thinking?” Do you ever think of hurting yourself?” Asking about suicide ideation does not give the person the idea or increase suicide risk. Most people are relieved to be able to discuss openly the painful feelings they have been struggling with in private (Kaplan & Sadock, 2004). If the patient answers in the affirmative, the therapist can ask follow-up questions: “Do you have a plan?” or “How would you carry out a suicide?” This information is pursued because the more specific the plan, the more likely the person is to hurt him/herself. Asking for specificity helps to determine the seriousness of intent.

Even so-called parasuicidal behaviors, such as cutting and self-mutilation, should be taken seriously. Understanding the person’s underlying motivation for self-harm is important. Briere (1996) makes a distinction between those who self-mutilate in an attempt to stay alive and those who attempt suicide and consider death a solution. Parasuicidal behaviors may reflect a reenactment of abuse dynamics with a physiologic basis associated with poor attachment and early abuse (van der Kolk, 1996). Chapter 2 describes the neurophysiology associated with reenactment of early trauma. These reenactments may be experienced as normal because they mirror early experiences. The person with borderline personality disorder may want attention in the context of an abandonment crisis and may escalate the threat and self-destruct in a desperate bid for attention. Because these individuals may be suicidal in the context of an abandonment crisis, talking about the loss sometimes may be enough to assuage the suicidal feelings.

The therapist must openly and honestly express concern and engage in problem solving with the patient so that a written plan can be developed. This collaborative plan should explicitly address the friends and community resources that would be available in an emergency so the patient can be safe. A safety plan should be developed for all patients who are thought to be at high risk for self-harm. Guidelines developed for by the International Society of Study for Dissociative Disorders with respect to suicidal behaviors can be applied to all patients who are at risk for self-harm. The guidelines state the following: “The safety plan may include a hierarchy of alternative behaviors, including contacting friends, leaving the setting where the patient feels unsafe, using symptom management strategies such as self-hypnosis, grounding, and containment techniques, using medications as needed, and finally, calling the therapist and waiting for a return call and/or going to the emergency department if the patient feels imminently unable to maintain safety” (ISSD, 2005, p. 20).

From a clinical and legal perspective, a written safety plan or a no-suicide contract, even if signed by the patient, is not a substitute for clinical judgment. Accurate assessment is imperative because the typical no-suicide contract may not be effective in a crisis situation, whether the patient is in the hospital or the community (Drew, 2001; Farrow, 2003). A safety contract is only as good as the therapeutic alliance. Safety may be especially compromised if the patient is inebriated or psychotic. Although nurses are used to dealing with life and death situations, they usually do not occur in private practice or without others around to help. The therapist is often in just that situation and must make decisions independently. It is safest to err on the side of caution and believe the intuition that tells you the person may hurt him/herself. Suicidal patients should be hospitalized immediately if the family or significant others cannot guarantee safety and the safety plan cannot be adhered to. The clinician must ensure that the patient is safe and may need to personally escort the patient to the emergency department if needed.

Other safety issues may need consideration, including the anorexic patient who is severely underweight (20% below the expected weight for their height) (Kaplan & Sadock, 2004); substance abuse patients who may overdose or pose a threat to others if inebriated and driving; actively self-mutilating patients; sexually promiscuous patients; and angry patients who want to hurt others. Each of these situations must be the first order of business in any treatment setting. Any acute mood disorder or psychosis, out-of-control substance abuse, or eating disorder may need to be treated in an inpatient program before traditional psychotherapy begins. If the patient comes to the session inebriated or high, the session should not be held, and the patient may need to be escorted to a safe place by the therapist, be sent home in a taxi, or have a friend or family member called to escort the person home.

The therapist’s safety must also be assessed. Some patients may be threatening, and the best predictor of violence has been found to be previous violent episodes (McWilliams, 2004). Often, intuition can tell you whether the patient may be violent, and it is better to err on the side of safety than to dismiss your feelings. Leaving your office door open and making sure that you are near the door may be warranted when working with hostile, unpredictable people, or it may be prudent to interview patients with a security guard nearby or with a colleague if you are working in a dangerous setting. One patient came to his session with a gun, which he told the advanced practice psychiatric nurse (APPN) about. He was asked to leave the gun at home for future sessions, which he agreed to, and psychotherapy proceeded as planned.

The First Contact

The first phone call with the patient begins the therapeutic alliance. Keeping the initial phone call as brief as possible is advised unless there are special circumstances. Occasionally, someone may ask whether you specialize in a particular problem or have had experience in a certain area, such as eating disorders or trauma. Answer the question factually, and refer the person elsewhere if that is warranted. Although at first you may not know what your areas of expertise are and feel you have none, it is probably best for you and the patients to start with populations and approaches with which you feel most comfortable. Knowing your own limits is essential, as is not using modalities with which you have little expertise, such as hypnosis, guided imagery, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), or expressive therapies, because in incompetent hands, patient regression may be triggered, and the blurring of fantasy and reality may occur.

The patient comes to the first session with expectations, even if the person has never been in psychotherapy before. Some of these expectations are obvious to the person, and some are not. Expectations can tell you about the person’s developmental level and what may be going on in the person’s relationships. For example, some patients with magical thinking fully expect to have their problems solved in a few sessions; those with dependency needs may expect to be taken care of or to be given advice; those who have been criticized expect to be disapproved of or judged; and those who eroticize relationships may expect the therapist to have sex with them. Sometimes, asking the person how s/he felt about coming to the session can help to elicit some idea of expectations. Asking if the patient has ever known anyone who was in therapy can also give valuable information about expectations. The patient may have known someone who was greatly helped by psychotherapy or may associate treatment with Woody Allen and endless, self-absorbed neurosis. Some therapists elicit this information by giving the patient an intake form, such as the Multimodal Life History Inventory (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1991). This questionnaire contains questions that address patients’ expectations regarding therapy. What do you think therapy is all about? How long do you think therapy should last? What personal qualities do you think the ideal therapist should possess?

The therapist’s office and seating arrangements are considered with respect to keeping the patient’s best interests in the foreground. Seating arrangements may be constrained if you are seeing patients in a clinic setting, but it is usually best not to sit behind a desk because this puts a barrier between you and the patient. However, sitting at the desk with the person on one side of the desk may be conducive to conversation. No matter what the setting, chairs ideally are set at approximately 3 to 4 feet away from each other and arranged so that the person is not directly across from you, but at a 45-degree angle. In this way, the patient does not feel scrutinized and compelled to make eye contact and can look away if s/he wishes.

For those who work in settings in which a comprehensive assessment is required in the initial session, Chapter 4 provides guidelines on how to accomplish this while effectively initiating a therapeutic alliance. For those who are in settings in which the assessment can be conducted over several sessions, Chapter 4 provides excellent resources and screening tools to incorporate to ensure a thorough and accurate assessment. If you are the prescribing advanced practice nurse only, guidelines for assessment on how to combine medication management with or without psychotherapy are discussed in Chapter 9. No matter what type of setting you are working in and how you proceed, practical arrangements for continuing the work, establishing goals, ending the session, and keeping records must be considered.

Making Practical Arrangements

Practical arrangements must be made regarding the frequency and length of the sessions. Weekly sessions of 45 to 50 minutes are usually scheduled unless there is a significant reason to deviate from this standard plan. The session begins and ends at predetermined times. Meeting less often usually is not as effective and interferes with the momentum of treatment, unless the goal of treatment is maintenance of the status quo or the APPN is prescribing only and another person is conducting the psychotherapy. It may be best to see the patient more often initially if you are concerned about safety or the person is in crisis. However, starting several times a week often is too intense for most people and may be threatening and counterproductive. The number of sessions per week may be increased after a solid therapeutic alliance is formed and the patient wishes to intensify the work for faster resolution.

Some brief psychotherapists advocate setting a termination date at the beginning of treatment, because it is thought that if the ending time is known, the goals and work may proceed faster. Toward the end of the time set, there can be renegotiation if more time is needed. Guidelines and principles for short-term psychotherapy are further discussed in Chapters 7, 8, and 14. Sometimes, therapists prefer to allow the process to unfold and leave the termination date open-ended unless there is a specified number of sessions that the person is allowed by the insurance company or there are agency constraints. Frequently, what the person initially came to therapy for evolves into something somewhat different as the process unfolds, and goals are revised periodically. For example, one man came into treatment because he felt depressed and unhappy with his work. As this was explored, he began to examine his long-standing dysthymia and how this related to a childhood traumatic experience that had violated his trust and impacted all dimensions of his life. The goals then focused on resolving his early trauma in light of his deepening awareness of its significance.

A Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)–type form explaining confidentiality and a contract delineating the terms of the psychotherapy can be given to the patient (see Appendixes I-6 and I-7, pp. 142 and 144), along with the packet of screening and assessment tools and can be signed and brought back to the next session. Some therapists also have a policy statement, posted in the waiting room, which describes consumer rights, confidentiality, missed sessions, and fees. A sample is available at www.guidetopsychology.com/compol.htm. Confidentiality is discussed, and whether you will be discussing information about the person to a supervisor other health care providers is disclosed. Permission for these discussions is authorized with a written release of information form, and care is taken to use discretion and reveal only what is necessary for medical care. If a treatment report requesting more sessions is to be sent to an insurance company, the form may be shared with the patient before sending it. In discussing patients with colleagues or in a professional forum such as a conference or paper, use a pseudonym or initial, and disguise identifying information to protect the person’s identity. Even though the person’s identity is kept confidential, permission should be obtained from the patient unless the information shared is an amalgam of cases and is not specifically about the patient.

Fees

Fees should be discussed during the first session. Novice nurse psychotherapists often feel conflicted about charging a fee for their services when they do not feel knowledgeable about what they are doing. Fees should reflect the level of education, the degree of expertise, and the going rate in the community for such services. Sometimes, beginning therapists overlook the extensive education and training required to do psychotherapy and the fact that to take care of the patient’s emotional needs, it is necessary to get paid for their professional services. You may decide to offer a certain percent of your patients a reduced fee, but having a pro bono practice in which you are paid by most of your patients less than others in your area is a recipe for resentment. Each therapist should decide on the basis of her finances whether a certain number of patients can be offered a lower fee and then fill that number of hours with low-fee or sliding-scale patients and refer others who cannot afford the standard fee to a low-cost clinic.

If the therapist is on the provider panel for that managed care company, the provider is contracted to charge a particular fee, and the patient pays a specified co-pay. Most therapists require payment at the end of the month for that month or the first session of the next month for the previous month. Other therapists expect payment at the end of each session. The provider submits the balance to the insurance company on an HCFA form and then gets paid by the managed care company or insurance company usually a month or more later. Psychotherapy sessions are given Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes that designate the type of service given for reimbursement. Box 3-2 provides common CPT codes used for psychotherapy services.

Box 3-2 Current Procedural Terminology Codes for Psychotherapy

90801 Psychological diagnostic interview

90802 Interactive psychiatric diagnostic interview using play equipment, etc

90805 20–30 minutes of individual psychotherapy with medication management

90806 Individual outpatient psychotherapy session, 45-50 minutes

90807 Individual psychotherapy medication management outpatient session, 45-50 minutes

90847 Family psychotherapy with patient present

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree