The Health Care Delivery System

Objectives

• Compare the various methods for financing health care.

• Explain the advantages and disadvantages of managed health care.

• Discuss the types of settings that provide various health care services.

• Discuss the role of nurses in different health care delivery settings.

• Differentiate primary care from primary health care.

• Explain the impact of quality and safety initiatives on delivery of health care.

• Discuss the implications that changes in the health care system have on nursing.

• Discuss opportunities for nursing within the changing health care delivery system.

Key Terms

Acute care, p. 18

Adult day care centers, p. 22

Assisted living, p. 21

Capitation, p. 15

Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), p. 15

Discharge planning, p. 19

Extended care facility, p. 20

Globalization, p. 27

Home care, p. 20

Hospice, p. 22

Independent practice association (IPA), p. 16

Integrated delivery networks (IDNs), p. 17

Managed care, p. 15

Medicaid, p. 20

Medicare, p. 20

Minimum Data Set (MDS), p. 21

Nursing informatics, p. 26

Nursing-sensitive outcomes, p. 26

Patient-centered care, p. 24

Pay for performance, p. 24

Primary health care, p. 17

Professional standards review organizations (PSROs), p. 15

Prospective payment system (PPS), p. 15

Rehabilitation, p. 20

Resource utilization groups (RUGs), p. 15

Respite care, p. 22

Restorative care, p. 20

Skilled nursing facility, p. 21

Utilization review (UR) committees, p. 15

Vulnerable populations, p. 27

Work redesign, p. 18

![]()

The U.S. health care system is complex and constantly changing. A broad variety of services are available from different disciplines of health professionals, but gaining access to services is often very difficult for those with limited health care insurance. Uninsured patients present a challenge to health care and nursing because they are more likely to skip or delay treatment for acute and chronic illnesses and die prematurely (Thompson and Lee, 2007). The continuing development of new technologies and medications, which shortens length of stay (LOS), also causes health care costs to increase. Thus health care institutions are managing health care more as businesses than as service organizations. Challenges to health care leaders today include reducing health care costs while maintaining high-quality care for patients, improving access and coverage for more people, and encouraging healthy behaviors (Knickman and Kovner, 2009). Health care providers are discharging patients sooner from hospitals, resulting in more patients needing nursing homes or home care. Often families provide care for their loved ones in the home setting. Nurses face major challenges to prevent gaps in health care across health care settings so individuals remain healthy and well within their own homes and communities.

Nursing is a caring discipline. Values of the nursing profession are rooted in helping people to regain, maintain, or improve health; prevent illness; and find comfort and dignity. The health care system of the new millennium is less service oriented and more business oriented because of cost-saving initiatives, which often causes tension between the caring and business aspects of health care (Knickman and Kovner, 2009). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2001) calls for a health care delivery system that is safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. The National Priorities Partnership is a group of 28 organizations from a variety of health care disciplines that have joined together to work toward transforming health care (National Priorities Partnership, 2008). The group has set the following national priorities:

• Patient and Family Engagement—Providing patient-centered, effective care

• Population Health—Bringing increased focus on wellness and prevention

• Safety—Eliminating errors whenever and wherever possible

• Care Coordination—Providing patient-centered, high-value care

• Overuse—Reducing waste to achieve effective, affordable care

The Institute of Medicine and Robert Woods Johnson Foundation (2011) put forth a vision for a transformed health care delivery system. The health care system of the future makes quality care accessible to all populations, focuses on wellness and disease prevention, improves health outcomes, and provides compassionate care across the life span. Transformations in health care are changing the practice of nursing. Nursing continues to lead the way in change and retain values for patient care while meeting the challenges of new roles and responsibilities. These changes challenge the nurse to provide evidence-based, compassionate care and continue in the role as patient advocate (Singleton, 2010). According to the IOM (2011) report, nurses need to be transformed by:

Health Care Regulation and Competition

Through most of the twentieth century, few incentives existed for controlling health care costs. Insurers or third-party payers paid for whatever the health care providers ordered for a patient’s care and treatment. As health care costs continued to rise out of control, regulatory and competitive approaches had to control health care spending. The federal government, the biggest consumer of health care, which paid for Medicare and Medicaid, created professional standards review organizations (PSROs) to review the quality, quantity, and cost of hospital care (Sultz and Young, 2006). Medicare-qualified hospitals had physician-supervised utilization review (UR) committees to review the admissions and to identify and eliminate overuse of diagnostic and treatment services ordered by physicians caring for patients on Medicare.

One of the most significant factors that influenced payment for health care was the prospective payment system (PPS). Established by Congress in 1983, the PPS eliminated cost-based reimbursement. Hospitals serving patients who received Medicare benefits were no longer able to charge whatever a patient’s care cost. Instead, the PPS grouped inpatient hospital services for Medicare patients into diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). Each group has a fixed reimbursement amount with adjustments based on case severity, rural/urban/regional costs, and teaching costs. Hospitals receive a set dollar amount for each patient based on the assigned DRG, regardless of the patient’s length of stay or use of services. Most health care providers (e.g., health care networks or managed care organizations) now receive capitated payments. Capitation means that the providers receive a fixed amount per patient or enrollee of a health care plan (Jonas et al., 2007). Capitation aims to build a payment plan for select diagnoses or surgical procedures that consists of the best standards of care at the lowest cost.

Capitation and prospective payment influences the way health care providers deliver care in all types of settings. Many now use DRGs in the rehabilitation setting, and resource utilization groups (RUGs) in long-term care. In all settings health care providers try to manage costs so the organizations remain profitable. For example, when patients are hospitalized for lengthy periods, hospitals have to absorb the portion of costs that are not reimbursed. This simply adds more pressure to ensure that patients are managed effectively and discharged as soon as is reasonably possible. Thus hospitals started to increase discharge planning activities, and hospital lengths of stay began to shorten. Because patients are discharged home as soon as possible, home care agencies now provide complex technological care, including mechanical ventilation and long-term parenteral nutrition.

Managed care describes health care systems in which the provider or health care system receives a predetermined capitated payment for each patient enrolled in the program. In this case the managed care organization assumes financial risk in addition to providing patient care. The focus of care of the organization shifts from individual illness care to prevention, early intervention, and outpatient care. If people stay healthy, the cost of medical care declines. Systems of managed care focus on containing or reducing costs, increasing patient satisfaction, and improving the health or functional status of individuals (Sultz and Young, 2006). Table 2-1 summarizes the most common types of health care insurance plans.

TABLE 2-1

| Type | Definition | Characteristics |

| Managed care organization (MCO) | Provides comprehensive preventive and treatment services to a specific group of voluntarily enrolled people. Structures include a variety of models: Staff model: Physicians are salaried employees of the MCO. Group model: MCO contracts with single group practice Network model: MCO contracts with multiple group practices and/or integrated organizations. Independent practice association (IPA): The MCO contracts with physicians who usually are not members of groups and whose practices include fee-for-service and capitated patients. | Focus is on health maintenance, primary care. All care is provided by a primary care physician. Referral is needed for access to specialist and hospitalization. It may use capitated payments. |

| Preferred provider organization (PPO) | Type of managed care plan that limits an enrollee’s choice to a list of “preferred” hospitals, physicians, and providers. An enrollee pays more out-of-pocket expenses for using a provider not on the list. | Contractual agreement exists between a set of providers and one or more purchasers (self-insured employers or insurance plans). Comprehensive health services are at a discount to companies under contract. Focus is on health maintenance. |

| Medicare | A federally administrated program by the Commonwealth Fund or the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS); a funded national health insurance program in the United States for people 65 years and older. Part A provides basic protection for medical, surgical, and psychiatric care costs based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs); also provides limited skilled nursing facility care, hospice, and home health care. Part B is a voluntary medical insurance; covers physician, certain other specified health professional services, and certain outpatient services. Part C is a managed care provision that provides a choice of three insurance plans. Part D is a voluntary Prescription Drug Improvement (Jonas et al, 2007). | Payment for plan is deducted from monthly individual Social Security check. It covers services of nurse practitioners. It does not pay full cost of certain services. Supplemental insurance is encouraged. |

| Medicaid | Federally funded, state-operated program that provides: (1) health insurance to low-income families; (2) health assistance to low-income people with long-term care (LTC) disabilities; and (3) supplemental coverage and LTC assistance to older adults and Medicare beneficiaries in nursing homes. Individual states determine eligibility and benefits. | It finances a large portion of care for poor children, their parents, pregnant women, and disabled very poor adults. It reimburses for nurse-midwifery and other advanced practice nurses (varies by state). It reimburses nursing home funding. |

| Private insurance | Traditional fee-for-service plan. Payment is computed after patient receives services on basis of number of services used. | Policies are typically expensive. Most policies have deductibles that patients have to meet before insurance pays. |

| LTC insurance | Supplemental insurance for coverage of LTC services. Policies provide a set amount of dollars for an unlimited time or for as little as 2 years. | It is very expensive. A good policy has a minimum waiting period for eligibility; payment for skilled nursing, intermediate, or custodial care and home care. |

| State Children’s Health Insurance Programs (SCHIP) | Federally funded, state-operated program to provide health coverage for uninsured children. Individual states determine participation eligibility and benefits. | It covers children not poor enough for Medicaid. |

In 2006 the National Quality Forum defined a list of 28 “Never Events” that are devastating and preventable. Examples of Never Events include patient death or serious injury related to a medication error or the administration of incompatible blood products. In 2007 Medicare ruled it would no longer pay for medical costs associated with these errors. Many states now require mandatory reporting of these events when they occur (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Network, n.d.).

Major health care reform came in 2010 with the signing into law of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Public Law No. 111-148). Health care reform of this magnitude has not occurred in the United States since the 1960s when Medicare and Medicaid were signed into law. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act focuses on the major goals of increasing access to health care services for all, reducing health care costs, and improving health care quality. Provisions in the law include insurance industry reforms that increase insurance coverage and decrease costs, increased funding for community health centers, increased primary care services and providers, and improved coverage for children (Adashi et al., 2010; HealthReform.gov, 2010).

Emphasis on Population Wellness

The United States health care delivery system faces many issues such as rising costs, increased access to services, a growing population, and improved quality of outcomes. As a result, the emphasis of the health care industry today is shifting from managing illness to managing health of a community and the environment.

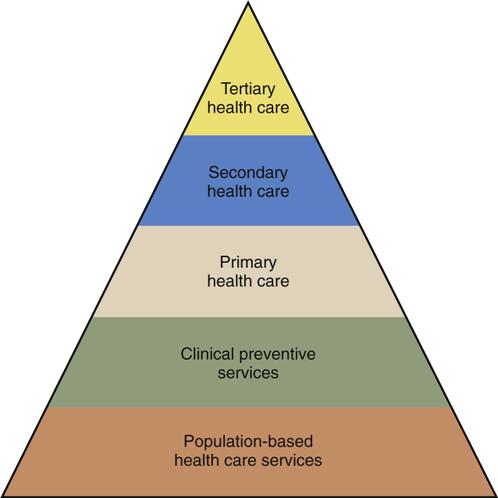

The Health Services Pyramid developed by the Core Functions Project serves as a model for improving the health care of U.S. citizens (Fig. 2-1). The pyramid shows that population-based health care services provide the basis for preventive services. These services include primary, secondary, and tertiary health care. Achievements in the lower tiers of the pyramid contribute to the improvement of health care delivered by the higher tiers. Health care in the United States is moving toward health care practices that emphasize managing health rather than managing illness. The premise is that in the long term, health promotion reduces health care costs. A wellness perspective focuses on the health of populations and the communities in which they live rather than just on finding a cure for an individual’s disease. Life expectancy for Americans is 77.9 years, which has shown a steady increase in the past century. Along with increased life expectancy, adult deaths related to coronary heart disease and stroke continue a long-term decreasing trend, and there is a decreasing trend in deaths of children since 1900 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, [CDC], 2007).The reduction in mortality rates has been credited to advancements in sanitation and prevention of infectious diseases (e.g., water, sewage, immunization, and crowded living conditions); patient teaching (e.g., dietary habits, decrease in tobacco use, and blood pressure control); and injury prevention programs (e.g., seat belt restraints, child seats, and helmet laws).

Health Care Settings and Services

Currently the U.S. health care system has five levels of care for which health care providers offer services: disease prevention; health promotion; and primary, secondary, and tertiary health care. The health care settings within which the levels of care are provided include preventive, primary, secondary, tertiary, restorative, and continuing care settings (Box 2-1). Larger health care systems have integrated delivery networks (IDNs) that include a set of providers and services organized to deliver a continuum of care to a population of patients at a capitated cost in a particular setting (Jonas et al., 2007). An integrated system reduces duplication of services across levels or settings of care to ensure that patients receive care in the most appropriate settings.

Changes unique to each setting of care have developed because of health care reform. For example, many health care providers now place greater emphasis on wellness, directing more resources toward primary and preventive care services. Nurses are especially important as patient advocates in maintaining continuity of care throughout the levels of care. They have the opportunity to provide leadership to communities and health care systems. The ability to find strategies that better address patient needs at all levels of care is critical to improving the health care delivery system.

Health care agencies seek accreditation and certification as a way to demonstrate quality and safety in the delivery of care and to evaluate the performance of the organization based on established standards. Accreditation is earned by the entire organization; specific programs or services within an organization earn certifications (The Joint Commission [TJC], 2011). The Joint Commission (formerly The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) accredits health care organizations across the continuum of care, including hospitals and ambulatory care, long-term care, home care, and behavioral health agencies. Other accrediting agencies have a specific focus such as the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) and the Community Health Accrediting Program (CHAP). Disease-specific certifications are available in most all chronic diseases (TJC, 2011). Accreditation and certification survey processes help organizations identify problems and develop solutions to improve the safety and quality of delivered care and services.

Preventive and Primary Health Care

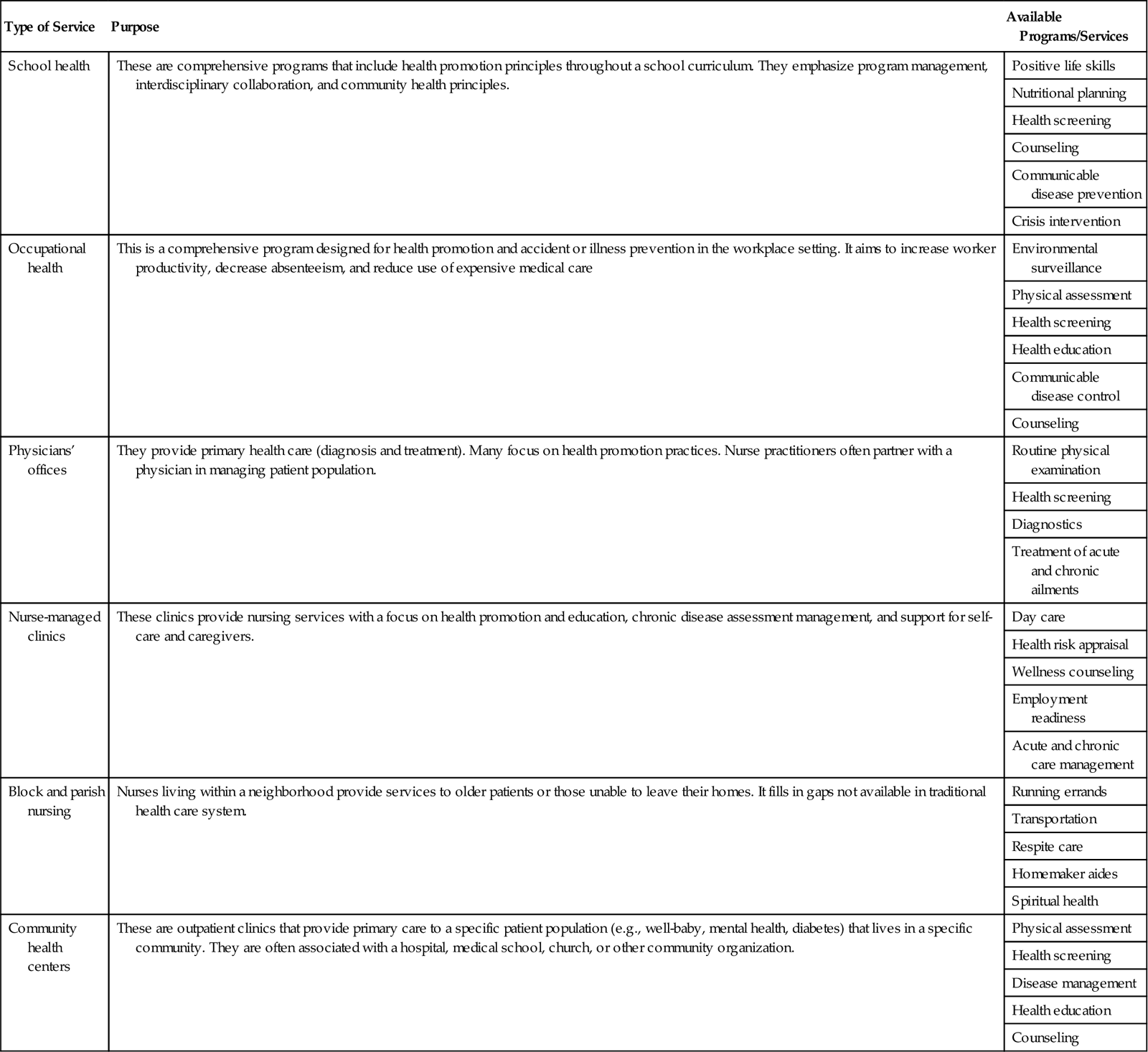

Primary health care focuses on improved health outcomes for an entire population. It includes primary care and health education, proper nutrition, maternal/child health care, family planning, immunizations, and control of diseases. Primary health care requires collaboration among health professionals, health care leaders, and community members. This collaboration needs to focus on improving health care equity, making health care systems person centered, developing reliable and accountable health care leaders, and promoting and protecting the health of communities (WHO, 2008). Successful community-based health programs take societal and environmental factors into consideration when addressing the health needs of communities (WHO, 2008). In settings in which patients receive preventive and primary care such as schools, physician’s offices, occupational health clinics, community health centers, and nursing centers, health promotion is a major theme (Table 2-2). Health promotion programs lower the overall costs of health care by reducing the incidence of disease, minimizing complications, and thus reducing the need to use more expensive health care resources. In contrast, preventive care is more disease oriented and focused on reducing and controlling risk factors for disease through activities such as immunization and occupational health programs. Chapter 3 provides a more comprehensive discussion of primary health care in the community.

TABLE 2-2

Preventive and Primary Care Services

| Type of Service | Purpose | Available Programs/Services |

| School health | These are comprehensive programs that include health promotion principles throughout a school curriculum. They emphasize program management, interdisciplinary collaboration, and community health principles. | Positive life skills |

| Nutritional planning | ||

| Health screening | ||

| Counseling | ||

| Communicable disease prevention | ||

| Crisis intervention | ||

| Occupational health | This is a comprehensive program designed for health promotion and accident or illness prevention in the workplace setting. It aims to increase worker productivity, decrease absenteeism, and reduce use of expensive medical care | Environmental surveillance |

| Physical assessment | ||

| Health screening | ||

| Health education | ||

| Communicable disease control | ||

| Counseling | ||

| Physicians’ offices | They provide primary health care (diagnosis and treatment). Many focus on health promotion practices. Nurse practitioners often partner with a physician in managing patient population. | Routine physical examination |

| Health screening | ||

| Diagnostics | ||

| Treatment of acute and chronic ailments | ||

| Nurse-managed clinics | These clinics provide nursing services with a focus on health promotion and education, chronic disease assessment management, and support for self-care and caregivers. | Day care |

| Health risk appraisal | ||

| Wellness counseling | ||

| Employment readiness | ||

| Acute and chronic care management | ||

| Block and parish nursing | Nurses living within a neighborhood provide services to older patients or those unable to leave their homes. It fills in gaps not available in traditional health care system. | Running errands |

| Transportation | ||

| Respite care | ||

| Homemaker aides | ||

| Spiritual health | ||

| Community health centers | These are outpatient clinics that provide primary care to a specific patient population (e.g., well-baby, mental health, diabetes) that lives in a specific community. They are often associated with a hospital, medical school, church, or other community organization. | Physical assessment |

| Health screening | ||

| Disease management | ||

| Health education | ||

| Counseling |

Secondary and Tertiary Care

In secondary and tertiary care the diagnosis and treatment of illnesses are traditionally the most common services. With the arrival of managed care, many now deliver these services in primary care settings. Disease management is the most common and expensive service of the health care delivery system. The acutely and chronically ill represent about 20% of the people in the United States, who consume about 80% of health care spending (CDC, 2007). Over 80% of adults 65 years of age have at least one chronic health condition that causes multiple health problems (Missouri Families, 2008).

Uninsured individuals are an increasing problem in health care. The fastest growing age-group of uninsured citizens is young adults between the ages of 19 and 34 (Billings and Cantor, 2009). Young adults turning 19 years of age from low-income families are in danger of being uninsured because of the inability to attend college and find employment with health care benefits. Coverage for young adults is important for various reasons. This age-group has a high incidence of obesity, pregnancy, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). People in this age-group are also less likely to see a doctor on a regular basis and follow up on a problem if they do not have health insurance. Lack of insurance rates varies by race. Statistics show that 34% of Hispanics, 19% of African Americans, and 10% of the white or Caucasian population do not have health insurance (CDC, 2010).

People who do not have health care insurance often wait longer before presenting for treatment; thus they are usually sicker and need more health care. As a result, secondary and tertiary care (also called acute care) is more costly. With the arrival of more advanced technology and managed care, physicians now perform simple surgeries in office surgical suites instead of in the hospital. Cost to the patient is lower in the office because the general overhead cost of the facility is lower.

Hospitals

Hospital emergency departments, urgent care centers, critical care units, and inpatient medical-surgical units provide secondary and tertiary levels of care. Quality, safe care is the focus of most acute care organizations; satisfaction with health care services is important to them. Patient satisfaction becomes a priority in a busy, stressful location such as the inpatient nursing unit. Patients expect to receive courteous and respectful treatment, and they want to be involved in daily care decisions. As a nurse, you play a key role in bringing respect and dignity to the patient (Vlasses and Smeltzer, 2007). Acute care nurses need to be responsive to learning patient needs and expectations early to form effective partnerships that ultimately enhance the level of nursing care given.

Because of managed care, the number of days patients can expect to be hospitalized is limited based on their DRGs on admission. Therefore nurses need to use resources efficiently to help patients successfully recover and return home. To contain costs, many hospitals have redesigned nursing units. Because of work redesign, more services are available on nursing units, thus minimizing the need to transfer and transport patients across multiple diagnostic and treatment areas.

Hospitalized patients are acutely ill and need comprehensive and specialized tertiary health care. The services provided by hospitals vary considerably. Some small rural hospitals offer only limited emergency and diagnostic services and general inpatient services. In comparison, large urban medical centers offer comprehensive, up-to-date diagnostic services, trauma and emergency care, surgical intervention, intensive care units (ICUs), inpatient services, and rehabilitation facilities. Larger hospitals also offer professional staff from a variety of specialties such as social service, respiratory therapy, physical and occupational therapy, and speech therapy. The focus in hospitals is to provide the highest quality of care possible so patients are discharged early but safely to home or another health care facility that will adequately manage remaining health care needs.

Discharge planning begins the moment a patient is admitted to a health care facility. Nurses play an important role in discharge planning in the hospital, where continuity of care is important. To achieve continuity of care, nurses use critical thinking skills and apply the nursing process (see Unit 3). To anticipate and identify the patient’s needs, nurses work with all members of the interdisciplinary health care team. They take the lead to develop a plan of care that moves the patient from the hospital to another level of health care such as the patient’s home or a nursing home. Discharge planning is a centralized, coordinated, interdisciplinary process that ensures that the patient has a plan for continuing care after leaving a health care agency.

Because patients leave hospitals as soon as their physical conditions allow, they often have continuing health care needs when they go home or to another facility. For example, a surgical patient requires wound care at home after surgery. A patient who has had a stroke requires ambulation training. Patients and families worry about how they will care for unmet needs and manage over the long term. Nurses help by anticipating and identifying patients’ continuing needs before the actual time of discharge and by coordinating health care team members in achieving an appropriate discharge plan.

Some patients are more in need of discharge planning because of the risks they present (e.g., patients with limited financial resources, limited family support, and long-term disabilities or chronic illness). However, any patient who is being discharged from a health care facility with remaining functional limitations or who has to follow certain restrictions or therapies for recovery needs discharge planning. All caregivers who care for a patient with a specific health problem participate in discharge planning. The process is truly interdisciplinary. For example, patients with diabetes visiting a diabetes management center requires the group effort of a diabetes nurse educator, dietitian, and physician to ensure that they return home with the right information to manage their condition. A patient who has experienced a stroke will not be discharged from a hospital until the team has established plans with physical and occupational therapists to begin a program of rehabilitation.

Effective discharge planning often requires referrals to various health care disciplines. In many agencies a health care provider’s order is necessary for a referral, especially when planning specific therapies (e.g., physical therapy). It is best to have patients and families participate in referral processes so they are involved early in any necessary decision making. Some tips on making the referral process successful include the following:

The nurse provides resources to improve the long-term outcomes of patients with limitations. Discharge planning depends on comprehensive patient and family education (see Chapter 25). Patients need to know what to do when they get home, how to do it, and for what to observe when problems develop. Patients require the following instruction before they leave health care facilities:

• Safe and effective use of medications and medical equipment

• Instruction in potential food-drug interactions and counseling on nutrition and modified diets

• Rehabilitation techniques to support adaptation to and/or functional independence in the environment

• Access to available and appropriate community resources

• When and how to obtain further treatment

• When to notify their health care provider for changes in functioning or new symptoms

Intensive Care

An ICU or critical care unit is a hospital unit in which patients receive close monitoring and intensive medical care. ICUs have advanced technologies such as computerized cardiac monitors and mechanical ventilators. Although many of these devices are on regular nursing units, the patients hospitalized within ICUs are monitored and maintained on multiple devices. Nursing and medical staff have special knowledge about critical care principles and techniques. An ICU is the most expensive health care delivery site because each nurse usually cares for only one or two patients at a time and because of all the treatments and procedures the patients in the ICU require.

Psychiatric Facilities

Patients who suffer emotional and behavioral problems such as depression, violent behavior, and eating disorders often require special counseling and treatment in psychiatric facilities. Located in hospitals, independent outpatient clinics, or private mental health hospitals, psychiatric facilities offer inpatient and outpatient services, depending on the seriousness of the problem. Patients enter these facilities voluntarily or involuntarily. Hospitalization involves relatively short stays with the purpose of stabilizing patients before transfer to outpatient treatment centers. Patients with psychiatric problems receive a comprehensive multidisciplinary treatment plan that involves them and their families. Medicine, nursing, social work, and activity therapy work together to develop a plan of care that enables patients to return to functional states within the community. At discharge from inpatient facilities, patients usually receive a referral for follow-up care at clinics or with counselors.

Rural Hospitals

Access to health care in rural areas has been a serious problem. Most rural hospitals have experienced a severe shortage of primary care providers. Many have closed because of economic failure. In 1989 the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) directed the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) to create a new health care organization, the rural primary care hospital (RPCH). The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 changed the designation for rural hospitals to Critical Access Hospital (CAH) if certain criteria were met (American Medical Association, 2009). A CAH is located in a rural area and provides 24-hour emergency care, with no more than 25 inpatient beds for providing temporary care for 96 hours or less to patients needing stabilization before transfer to a larger hospital. Physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants staff a CAH. The CAH provides inpatient care to acutely ill or injured people before transferring them to better-equipped facilities. Basic radiological and laboratory services are also available.

With health care reform, more big-city health care systems are branching out and establishing connections or mergers with rural hospitals. The rural hospitals provide a referral base to the larger tertiary care medical centers. With the development of advanced technologies such as telemedicine, rural hospitals have increased access to specialist consultations. Nurses who work in rural hospitals or clinics require competence in physical assessment, clinical decision making, and emergency care. Having a culture of evidence-based practice is important in rural hospitals so nurses practice using the best evidence to achieve optimal patient outcomes (Burns et al., 2009). Advanced practice nurses (e.g., nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists) use medical protocols and establish collaborative agreements with staff physicians.

Restorative Care

Patients recovering from an acute or chronic illness or disability often require additional services to return to their previous level of function or reach a new level of function limited by their illness or disability. The goals of restorative care are to help individuals regain maximal functional status and enhance quality of life through promotion of independence and self-care. With the emphasis on early discharge from hospitals, patients usually require some level of restorative care. For example, some patients require ongoing wound care and activity and exercise management until they have recovered enough following surgery to independently resume normal activities of daily living.

The intensity of care has increased in restorative care settings because patients leave hospitals earlier. The restorative health care team is an interdisciplinary group of health professionals and includes the patient and family or significant others. In restorative settings nurses recognize that success depends on effective and early collaboration with patients and their families. Patients and families require a clear understanding of goals for physical recovery, the rationale for any physical limitations, and the purpose and potential risks associated with therapies. Patients and families are more likely to follow treatment plans and achieve optimal functioning when they are involved in restorative care.

Home Health Care (Home Care)

Home care is the provision of medically related professional and paraprofessional services and equipment to patients and families in their homes for health maintenance, education, illness prevention, diagnosis and treatment of disease, palliation, and rehabilitation. Nursing is one service most patients use in home care. However, home care also includes medical and social services; physical, occupational, speech, and respiratory therapy; and nutritional therapy. These services usually occur once or twice a day for as long as 7 days a week. A home care service also coordinates the access to and delivery of home health equipment, or durable medical equipment, which is any medical product adapted for home use.

Health promotion and education are traditionally the primary objectives of home care, yet at present most patients receive home care because they need nursing or medical care. Examples of home nursing care include monitoring vital signs; assessment; administering parenteral or enteral nutrition, medications, and IV or blood therapy; and wound or respiratory care. The focus is on patient and family independence. Nurses address recovery and stabilization of illness in the home and identify problems related to lifestyle, safety, environment, family dynamics, and health care practices.

Approved home care agencies usually receive reimbursement for services from the government (such as Medicare and Medicaid in the United States), private insurance, and private pay. The government has strict regulations that govern reimbursement for home care services. An agency cannot simply charge whatever it wants for a service and expect to receive full reimbursement. Government programs set the cost of reimbursement for most professional services.

Nurses in home care provide individualized care. They have a caseload and assist patients in adapting to permanent or temporary physical limitations so they are able to assume a more normal daily home routine. Home care requires a strong knowledge base in many areas such as family dynamics (see Chapter 10), cultural practices (see Chapter 9), spiritual values (see Chapter 35), and communication principles (see Chapter 24).

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation restores a person to the fullest physical, mental, social, vocational, and economic potential possible. Patients require rehabilitation after a physical or mental illness, injury, or chemical addiction. Specialized rehabilitation services such as cardiovascular, neurological, musculoskeletal, pulmonary, and mental health rehabilitation programs help patients and families adjust to necessary changes in lifestyle and learn to function with the limitations of their disease. Drug rehabilitation centers help patients become free from drug dependence and return to the community.

Rehabilitation services include physical, occupational, and speech therapy and social services. Ideally rehabilitation begins the moment a patient enters a health care setting for treatment. For example, some orthopedic programs now have patients perform physical therapy exercises before major joint repair to enhance their recovery after surgery. Initially rehabilitation usually focuses on the prevention of complications related to the illness or injury. As the condition stabilizes, rehabilitation helps to maximize the patient’s functioning and level of independence.

Rehabilitation occurs in many health care settings, including special rehabilitation agencies, outpatient settings, and the home. Frequently patients needing long-term rehabilitation (e.g., patients who have had strokes and spinal cord injuries) have severe disabilities affecting their ability to carry out the activities of daily living. When rehabilitation services occur in outpatient settings, patients receive treatment at specified times during the week but live at home the rest of the time. Health care providers apply specific rehabilitation strategies to the home environment. Nurses and other members of the health care team visit homes and help patients and families learn to adapt to illness or injury.

Extended Care Facilities

An extended care facility provides intermediate medical, nursing, or custodial care for patients recovering from acute illness or those with chronic illnesses or disabilities. Extended care facilities include intermediate care and skilled nursing facilities. Some include long-term care and assisted living facilities. At one point extended care facilities primarily cared for older adults. However, because hospitals discharge their patients sooner, there is a greater need for intermediate care settings for patients of all ages. For example, health care providers transfer a young patient who has experienced a traumatic brain injury resulting from a car accident to an extended care facility for rehabilitative or supportive care until discharge to the home becomes a safe option.

An intermediate care or skilled nursing facility offers skilled care from a licensed nursing staff. This often includes administration of IV fluids, wound care, long-term ventilator management, and physical rehabilitation. Patients receive extensive supportive care until they are able to move back into the community or into residential care. Extended care facilities provide around-the-clock nursing coverage. Nurses who work in a skilled nursing facility need nursing expertise similar to that of nurses working in acute care inpatient settings, along with a background in gerontological nursing principles (see Chapter 14).

Continuing Care

Continuing care describes a variety of health, personal, and social services provided over a prolonged period. These services are for people who are disabled, who were never functionally independent, or who suffer a terminal disease. The need for continuing health care services is growing in the United States. People are living longer, and many of those with continuing health care needs have no immediate family members to care for them. A decline in the number of children families choose to have, the aging of care providers, and the increasing rates of divorce and remarriage complicate this problem. Continuing care is available within institutional settings (e.g., nursing centers or nursing homes, group homes, and retirement communities), communities (e.g., adult day care and senior centers), or the home (e.g., home care, home-delivered meals, and hospice) (Meiner, 2011).

Nursing Centers or Facilities

The language of long-term care is confusing and constantly changing. The nursing home has been the dominant setting for long-term care (Meiner, 2011). With the 1987 OBRA, the term nursing facility became the term for nursing homes and other facilities that provided long-term care. Now nursing center is the most appropriate term. A nursing center typically provides 24-hour intermediate and custodial care such as nursing, rehabilitation, dietary, recreational, social, and religious services for residents of any age with chronic or debilitating illnesses. In some cases patients stay in nursing centers for room, food, and laundry services only. Most persons living in nursing centers are older adults. A nursing center is a resident’s temporary or permanent home, with surroundings made as homelike as possible (Sorrentino, 2007). The philosophy of care is to provide a planned, systematic, and interdisciplinary approach to nursing care to help residents reach and maintain their highest level of function (Resnick and Fleishell, 2002).

According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, just over 5% of people 65 years of age and older live in nursing centers and other facilities (Missouri Families, 2008). The nursing center industry is one of the most highly regulated industries in the United States. These regulations have raised the standard of services provided (Box 2-2). One regulatory area that deserves special mention is that of resident rights. Nursing facilities have to recognize residents as active participants and decision makers in their care and life in institutional settings (Meiner, 2011). This also means that family members are active partners in the planning of residents’ care.