12 The end of the journey

discharge from hospital and the experience of death

• To enable the student to gain an understanding of the discharge process from hospital for the patient

• To enable the student to understand that the end of the journey for a patient might be death

• To understand what end of life care means for the patient and their family

• To explore sudden death and enable the student to reflect on their role when this happens

• To enable the student to identify their learning and development needs in relation to death and dying

Introduction

Wherever your medical placement is, your patients will ultimately be discharged home from the service they are currently using. So, if you are placed in a hospital ward or department, the patient will be discharged back to their home and, for some, this could mean a care home or similar environment. Sometimes patients are discharged home on the same day if you are in an investigations unit, or after a few days if you are on a medical ward. In an intermediate care setting or virtual setting (see Ch. 2), there may be a fixed length of time the patient will stay, for example 6 weeks, and then their care would be transferred elsewhere or they would be discharged home. Patients with long-term medical conditions may remain within the service, for example under the care of a medical consultant or clinical nurse specialist visiting out-patients, for the rest of their life.

Planning for discharge from hospital

As your patients will not expect or want to stay in hospital any longer than is necessary, it is essential that discharge planning begins on admission. Discharge planning should be an ongoing process throughout a patient’s stay. It requires the multidisciplinary team to work together with the patient and their carer, if appropriate, to identify what will be required for the patient to be discharged home safely and in a timely manner – that is, as soon as they are medically well enough. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) Standards (2010) contain a number of competencies that are relevant to discharge planning, so should form part of your learning outcomes. They expect the following:

• You will understand the roles and responsibilities of other health and social care professionals and seek to work with them collaboratively for the benefit of all people in need of care.

• You will work with the person and others to make sure that they are actively involved in decision making in order to maintain their independence and take account of their ongoing intellectual, physical and emotional needs.

• You will use verbal, non-verbal and written communication to listen, recognise, interpret and record people’s knowledge and understanding of their needs. You must share information with others while respecting individual rights to confidentiality.

• You will work closely with individuals, groups and carers, using a range of skills to carry out comprehensive, systematic and holistic assessments. These must take into account current and previous physical, social, cultural, psychological, spiritual, genetic and environmental factors that may be relevant to the individual and their families.

• You will recognise when the complexity of clinical decisions may need specialist knowledge and expertise and then consult or refer accordingly.

• You will work effectively across professional and agency boundaries, respecting and making the most of the contributions made by others to achieve integrated person-centred care.

• You will work as an independent practitioner as well as part of a team, taking a leadership role in coordinating, delegating and supervising care safely and appropriately while remaining accountable.

The majority of discharges will be simple discharges – that is, those patients who are being discharged back to their own homes with simple ongoing needs that do not require any complex planning or delivery (Department of Health (DH) 2004).

The Department of Health (2010) has recommended 10 steps to help achieve a safe and timely discharge from hospital (see Box 12.1).

Box 12.1 The 10 steps to achieve a safe and timely discharge from hospital (DH 2010)

1. Start planning for discharge or transfer before or on admission.

2. Identify whether the patient has simple or complex discharge and transfer planning needs, involving the patient and carer in your decision.

3. Develop a clinical management plan for every patient within 24 hours of admission.

4. Coordinate the discharge or transfer of care process through effective leadership and handover of responsibilities at ward level.

5. Set an expected date of discharge or transfer within 24–48 hours of admission, and discuss with the patient and carer.

6. Review the clinical management plan with the patient each day, take any necessary action and update progress towards the discharge or transfer date.

7. Involve patients and carers so that they can make informed decisions and choices that deliver a personalised care pathway and maximise their independence.

8. Plan discharges and transfers to take place over 7 days to deliver continuity of care for the patient.

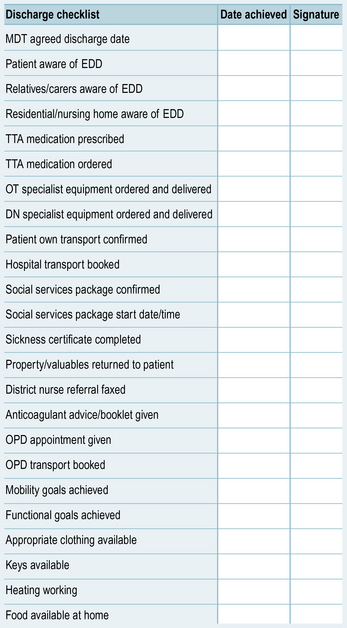

9. Use a discharge checklist 24–48 hours prior to transfer.

10. Make decisions to discharge and transfer patients each day.

Expected (estimated) dates of discharge

The checklist in Figure 12.1 includes many of the things that need to be considered and confirmed before your patient is ready to go home. All of these will not necessarily apply to all patients.

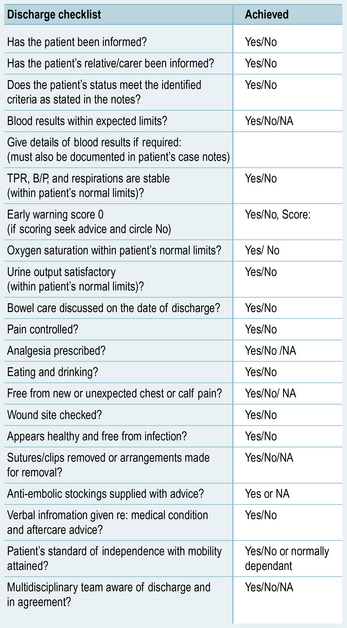

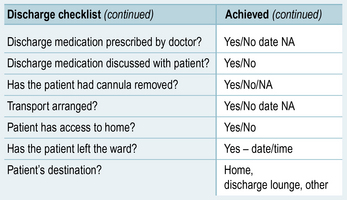

By the time your patient reaches their expected date of discharge, all of the items on the checklist should have been confirmed and any community services needed should be ready to start. On the day of discharge, your patient may need to be examined by their doctor to ensure they are well enough to leave hospital. Some wards may operate a nurse-led discharge system, where a senior nurse can assess the patient on the day of discharge to determine if they are ready to be discharged. Figure 12.2 shows some of the things a nurse will be required to check prior to discharging a patient under a nurse-led discharge system.

End of life care

As mentioned previously, some patients may not be ending their time in hospital by going home, and will in fact be entering the end stages of their long-term condition and will require end of life care. For some patients, dying in hospital may be their preferred option, but for many, they may wish to die at home or in another organisation such as a hospice. Some of you may have a placement in a hospice, and more about this kind of care can be found in Howard and Chady (2012), another book in this series.

There has been growing awareness of the need for good end of life care recently, and this has been supported by a number of initiatives and guidance from the Department of Health, most notably the End of Life Care Strategy (DH 2008).

What is palliative care?

The World Health Organization (WHO; 2011) defines palliative care as:

Palliative care aims to do the following (WHO 2011):

• Affirm life and regard dying as a normal process.

• Neither hasten nor postpone death.

• Provide relief from pain and other distressing symptoms.

• Integrate the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care.

• Offer a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death.

• Offer a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and their own bereavement.

• Use a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counselling if indicated.

• Enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness.

• Is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.

A number of nationally recognised tools are used to ensure the standard of care provided at the end of life meets the needs of patients and relatives. Some of the ones used in your placement area may include the Liverpool Care Pathway, the Gold Standards Framework and the Preferred Place of Care (The Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute 2010). Ask your mentor if any of these are used in your area.

Liverpool Care Pathway

Care pathways are tools that are used to direct care for a particular group of patients or health problems, ensuring care is standardised, evidence-based and patient centred while also providing a method of monitoring the care given for clinical governance purposes (Vanhaecht et al 2011).

The following link will take you to more information about the LCP and a sample LCP. See also Chapter 2 in Ellershaw and Wilkinson (2011) for information on how the LCP should be used:

http://www.liv.ac.uk/mcpcil/liverpool-care-pathway/documentation-lcp.htm (accessed July 2011).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree