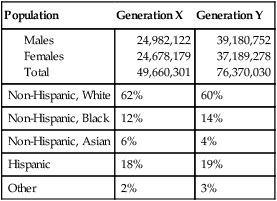

The most recent National League for Nursing (NLN) (2009a) survey of nursing programs indicated that only 14% of baccalaureate students were over the age of 30. In contrast, the percentage of prelicensure students over age 30 enrolled in associate degree and diploma programs remains high at nearly 50%. More than 60% of students enrolled in graduate nursing programs are over the age of 30, and nearly 70% of those in doctoral programs are over the age of 40. This wide range of age diversity among students in nursing offers unique challenges to nurse educators when these students are mixed in classrooms. Degree transition and graduate programs in nursing have seen an increase in enrollment. Baccalaureate completion programs, such as RN to BSN and accelerated option programs, have incurred increased popularity with steady increases in enrollment of 8.2% and nearly 10%, respectively (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2009). In 2008, nursing master’s degree programs saw an increase of nearly 18% enrollment as well (U.S. Department of Education, 2009). The college student population is also becoming more representative of the increasing cultural diversity that exists in American society. Of all college students, 32.2% are minority students (U.S. Department of Education, 2009). In nursing, baccalaureate minority representation remains high at 26%, and master’s programs have increased to 24% (AACN, 2009). Competition for admission into baccalaureate, associate, and master’s degree nursing schools remains significant, which also shifts the demographic profile of the student nurse. Of all qualified applications submitted to prelicensure nursing schools in 2007–2008, only 42.3% were accepted (AACN, 2009). The major reasons for turning away qualified applicants, as reported by nursing schools, include a shortage of faculty, insufficient clinical teaching sites, limited classroom space, lack of preceptors, and budget cuts (AACN, 2009). At the same time, faculty and administrators are challenged to continue to recruit qualified, diverse student bodies and to maintain high academic standards and outcomes despite a critical shortage of resources. Millennials, or Generation Y, are persons born between the late 1970s and mid to late 1990s. They are described as “the next great generation” and outnumber any previous generation at around 76 million strong (U.S. Census Bureau, 2007). Millennials grew up as highly valued children of the Generation X “baby busters” and are generally described as optimistic, team-oriented, high-achieving rule-followers. Aptitude test scores among this group have risen across all grade levels, and the pressure to succeed has risen likewise (Howe & Strauss, 2000). Millennials characteristically have good relationships with their parents and families and share their interests in music and travel. Parents of Millennials are involving their children in academic and sports activities at younger ages to prepare them for success. Millennials are accustomed to living highly structured lives planned by their parents and have had very little free time. By the time they reach college, they have learned how to work with others and be a member of a team. Group grades for projects and assignments are something they are used to and expect (Johnson & Romanello, 2005). Implications for nurse educators in dealing with this generation include providing immediate feedback and structure in the classroom, providing for the safety of the students on campus and in clinical sites, and providing opportunities for service and giving back to their communities. Millennial learners are technologically savvy and comfortable with multitasking, and value doing rather than knowing. They are “digital natives,” having grown up with technology (Elam, Stratton, & Gibson, 2007); however, this can sometimes be a barrier to critical thinking, as students may have difficulties refining their abilities to focus on priority issues. Millennials as a group are more diverse than previous generations: 36% are nonwhite or Hispanic (Walker et al., 2006) and 20% have an immigrant parent (Howe & Strauss, 2000). The parents of this generation expect that their children’s schools and universities will reflect diversity and thus provide a richer learning experience. Graduate and second degree students like the use of distance technologies such as web-based courses. Such teaching modalities can result in positive student perceptions, high satisfaction, and achievement of learning outcomes. These nontraditional students often find the convenience of online or hybrid formats (those offered online and face-to-face) more convenient for their lifestyles (Ali, Hodson-Carlton, & Ryan, 2004). Generation Xers represent a smaller cohort (50 million) of those born between 1965 and 1976 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). They are more diverse in race and ethnicity than previous generations, but not as diverse as their counterpart Millennials. These are children of baby boomers and their work ethics and loyalty differ from those of their parents. Many are children of divorced parents and thus “latchkey” kids. This generation was the first to demonstrate a need for work–life balance and self-sufficiency, coining the phrase “what’s in it for me?” Generation Xers are comfortable with change and technology, as their members have participated in the development of Google, YouTube, and Amazon (Johnson & Romanello, 2005; Stephey, 2008). See Table 2-1 for a comparison of demographic characteristics of Generation X and Generation Y students. Table 2-1 Generation X and Generation Y Demographic Characteristics, 2009 Data from: U.S. Census Bureau, National Population Estimates and Projections. The implications of such generational demographics are significant to nursing faculty and the profession as a whole. Teaching strategies that successfully engage the Millennial learner need to be interactive, group focused, objective, and experiential (Elam et al., 2007). Older students who are returning to school with multiple role responsibilities may require support resources such as tutoring, remediation, day care, and the opportunity for part-time study (Swail, 2002). Graduate students may find that the use of online or hybrid programs meets their scheduling demands much better than traditional classroom formats (Ali et al., 2004). Incorporating a variety of teaching strategies, such as the teacher-centered lecture, as well as entertaining interactive, web-based media, that appeal to multigenerational students recognizes both groups’ learning needs and preferences. Faculty can benefit from the diverse generational component in their classes. A prime example would be to have intergenerational students respond to questions as a group, which would demonstrate the varying perceptions related to life experiences (Johnson & Romanello, 2005). Faculty must prepare for an increasingly diverse student body by closely examining the changing demographics of their student body, the adequacy of support services for the adult learner in their institution, and the flexibility of nursing curricula in their program. Currently men occupy about 6.6% of the nurse population (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010) and nearly 14% of the prelicensure student population (NLN, 2009a). Numbers continue to grow through increased enrollment in schools of nursing due to the job flexibility and diverse career opportunities (Ellis, Meeker, & Hyde, 2006). According to the NLN (2009c), men comprise 12% of students in baccalaureate programs, 11% of master’s students, and 10% of students in doctoral programs. While encouraging, there remains an imbalance in gender enrollment in nursing programs as well as evidence of male students not completing their respective educational programs (Stott, 2007). Various studies indicate the possibility of barriers in the professional schools that lead male students to feel marginalized and, in some cases, even to abandon their career choice before graduating (Bell-Scriber, 2008; Ellis et al., 2006; O’Lynn, 2004; Smith, 2006; Stott, 2007). Nursing faculty are compelled to recognize barriers perceived by men in schools of nursing and seek to rectify them. Male nursing students present with their own perceptions and needs. In a study performed by Smith (2006), an interview of 29 male nursing students identified three major themes: (1) pressures of balancing family, work, and school, (2) perceptions of nursing, and (3) clients refusing to be cared for by a male nurse. Bell-Scriber (2008) identified that use of sexist language in the classroom and textbooks creates a less inviting classroom for male students. In another study, Ellis et al. (2006) determined that curricula in nursing programs are designed for female learners. As one respondent suggested, the curriculum was “set up by women, for women,” especially in relation to testing, classroom lecture and discussion, and course structure. O’Lynn’s (2004) study identified that male nursing history is not emphasized in classroom discussion and lecture. In addition, textbooks frequently underrepresent men in the nursing profession and faculty refer to nurses in a female context in the classroom. Stott (2007) used tape-recorded interviews and diaries written by the participants to determine factors influencing male nursing students’ course completion. The presence of male role models in nursing education was identified as important for student support and inspiration (Stott, 2007). However, lack of these role models creates self-doubt and social isolation in male students, potentially contributing to increased drop-out rates. The use of sexist language, lack of role models, and a biased curriculum all present as barriers to the successful recruitment and retention of male students in schools of nursing and, subsequently, the profession. Smith (2006) offered several strategies for nursing programs to develop and implement in order to respond positively to the minority of men in nursing: (1) develop peer support systems, (2) link male students with academic leadership to share experiences and concerns, (3) collect data regarding client refusal of care by male students and develop guidelines to address such issues, and (4) select texts and case studies that reflect both males and females in the nursing profession. These strategies could also be implemented for other minority students. In 2004 the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce, in its report Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions, described a lag in the ethnic diversity of all health professions. While nearly 25% of the population is represented by African Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians, these groups account for less than 9% of nurses and even lower percentages of physicians and dentists. Despite an emphasis on recruitment of ethnically diverse students, there continues to be an underrepresentation of minorities in schools of nursing and in the profession. According to the Health Resources and Services Administration survey of registered nurses (U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, 2010), nearly 16.8% of practicing RNs identified themselves as belonging to a minority group. In 2008–2009 data collected on the ethnicity of baccalaureate nursing students, 26.3% of students were identified as minority students. Of that population, 14% were black, 4% were Pacific-Asian, 6% were Hispanic, and 1.5% were American Indian. The proportion of minority students in master’s and doctoral programs increased to 25.6% and 23.0%, respectively (AACN Annual Report, 2009). Although there was a 3% increase in minority enrollment from 2005 to 2009 (NLN, 2009b), the profession is challenged to continue to meet the demands of a growing workforce need and recruitment of minorities and males into the profession. Students with racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds can face a number of barriers that hamper their ability to succeed in college. Cultural differences between and within faculty and student groups, gender and generational differences as previously discussed, and a lack of rigorous academic preparation are thought to contribute to the difficulty of teaching a diverse student body (Bednarz, Schim, & Doorenbos, 2010). The most common barriers are the lack of racially and ethnically diverse faculty, lack of student finances, and lack of academic preparedness (Beacham, Askew, & Williams, 2009; Gardner, 2005a; Martin-Holland et al., 2003). There is a parallel need to recruit more faculty from diverse racial, ethnic, and gender minorities. According to 2009 data from AACN member schools, only 11.6% of full-time nursing faculty members come from minority backgrounds and only 5.1% are male. A lack of racial, ethnic, and gender diversity among faculty represented in nursing is a reflection of the failure to recruit and retain the same diversity in the undergraduate and graduate student population. Furthermore, the lack of ethnically diverse faculty can perpetuate a culture of insensitivity to the needs of those ethnically diverse students. In a research study analyzing perceived existing educational barriers in nursing schools, 26 faculty and 17 ethnically diverse nurses who graduated from an associate or baccalaureate nursing program within the last 2 years were interviewed (Amaro, Abriam-Yago, & Yoder, 2006). Throughout the interview process, several themes related to educational barriers emerged: (1) personal needs (lack of finances, time issues, family responsibilities and obligations, and difficulties related to language and communication); (2) academic needs (workload); (3) language needs (difficulty reading and understanding assignments, prejudice due to accents, verbal communication barriers); and (4) cultural needs (expectations related to assertiveness and cultural norm, lack of diverse role models, and difficulty with communication). Intolerance by faculty and peers were found to exist for these nurses during their educational experience. Faculty need to embrace the cultural differences of their students and use available resources to foster a successful learning environment. Collaboration with ethnic student associations on campus could assist faculty to promote learning among their culturally diverse student population. Furthermore, faculty could work to promote student success by offering access to role models, peer support and encouragement, tutoring opportunities, and communication strategies. Financial problems are a major stressor for minority students. Rising tuition costs and other fees, coupled with a reduction in government support for higher education, affect all students but may be particularly difficult for minority students. Minority students are often the first in their family to seek higher education. They often come from low-income households and therefore their families may lack the necessary financial resources to support their education. Financial aid in the form of loans or scholarships is becoming more competitive, and less money is available (Brown, Santiago, & Lopez, 2003). Insufficient academic preparation and lack of support can also prevent ethnically diverse students from completing their program of study. Many Latino youth are in schools with few academic and physical resources and are thus not prepared for the academic challenges of a nursing program (Brown et al., 2003). Many colleges offer special enrichment programs to help students achieve basic academic skills, as well as adjust to the college learning environment. Through academic advisement, skills assessment, and assistance with developing study skills, students can be helped to achieve a better academic record. For example, Mount Carmel’s Learning Trail student success program assists Hispanic students to be successful by providing mentoring, tutoring, counseling, and follow-up. More than 80% of the students in the program graduate (Martinez & Martinez, 2003). Stewart and Cleveland (2003) described a program to introduce middle and high school students to college and nursing. The Wisconsin Youth in Nursing program recruited minority youth with a high grade point average (GPA) and the motivation to complete the program. Twenty-three students participated in the 2-week summer residential program on a college campus. The program included general education and nursing courses, and the students were in class all day, 5 days a week. The nursing segment included classes on careers in nursing, introduction to nursing, pathophysiology, and case studies. Students also worked on computers and were taught some nursing skills, including physical assessment skills. Students evaluated the program as being very successful. Faculty will follow the participants to determine how many were successful in gaining admission to a nursing school. For many students, English is an additional language (EAL), and the students may speak one language at home and English at school. Most studies of EAL have examined Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian students, but ignored other significant immigrant African students. Several studies have found that EAL students experience several barriers such as lack of self-confidence, reading/writing and learning difficulties, isolation, prejudice, and lack of family and financial support (Starr, 2009). Although the recruitment and retention of racially and ethnically diverse students in the nursing profession is an important issue, little research is available on the effectiveness of various recruitment and retention efforts directed toward these students (Gardner, 2005a; Villarruel, Canales, & Torres, 2001). It is important to acknowledge that many nursing programs rely on standardized tests and GPAs as criteria for admission. These types of recruitment strategies do not take into account the educational experience of many minority students and constitute a “relentless exclusion based on academic adequacy and who will pass the NCLEX-RN exam” (McQueen & Zimmerman, 2004, p. 52). It is painfully obvious to potential applicants who are socially or economically disadvantaged, particularly when a limited number of admission slots are available, that they will be excluded when admissions are determined by GPA alone. Such a selection process also has been called a biased response to scarce resources (McQueen & Zimmerman, 2004). The outcome is that only a few diverse students are admitted, and many of those tend to be labeled “high-risk.” In a study conducted by Soroff, Rich, Rubin, Strickland, and Plotnick (2002), the absence of diverse role models for nursing students affected both recruitment and retention efforts to increase diversity within their student population. It was important for students to see faculty from their racial or ethnic group functioning successfully in a variety of leadership positions in the university setting (Soroff et al., 2002). Practicing minority nurses can be encouraged to function as role models and mentors. Many nursing students plan to practice in a hospital or community setting after graduation, and matching them with a practicing nurse is a way to instill confidence in them that they can be successful. Nursing school faculty could work with their school’s alumni association and with diverse nursing groups to provide role models for students. Faculty commitment is crucial to the success of all students, and those students who must also overcome barriers need a student–faculty relationship with a faculty member who is not responsible for assigning a grade to them. An example of successful mentoring is a program developed by the University of Southern California. At the beginning of each semester, at-risk students are identified and offered study skills workshops, peer tutors, study groups, and faculty coaches. Success was determined by the evidence that at-risk minority students were passing at similar rates to students who were not considered at risk (Peter, 2005). It is essential for all faculty members and administrators to develop sensitivity with regard to the diversity of the students on their campus and awareness of the needs of these students. Faculty commitment to student success results in more successful students. Faculty members who represent the dominant race at the school can also assist in the recruitment and retention of minority students by modeling a commitment to developing cultural competence among the faculty (Campinha-Bacote, 2010; Pacquiao, 2007). Assessment of faculty cultural competence is an important step in gaining commitment and support of the value of working with racially and ethnically diverse students and colleagues. Campinha-Bacote (2010) developed a cultural competence assessment tool (IAPCC-M) according to her model of cultural competence to assist in developing a culturally competent mentoring program for faculty. Use of culturally conscious mentoring programs can help improve the success of minority and other diverse students in nursing programs. In the model, cultural competence is viewed as a process that involves the integration of cultural awareness to achieve competence in mentoring. Using the ASKED (Awareness, Skill, Knowledge, Encounters, and Cultural Desire) model as a basis for developing a mentoring program could help address the critical need for increasing and retaining diverse students in nursing programs. (See also Chapter 17.) Participating in special support programs can increase the chance of academic success for culturally diverse students. Many schools of nursing have identified and implemented strategies focused on securing the success of the culturally diverse student. At California State University, a Minority Retention Project (MRP) was developed to improve the retention and success of its minority students (Gardner, 2005b). The MRP was designed based on Dr. Vincent Tinto’s Theory of Student Retention (1993) that those students who felt connected and committed to their educational institution were more likely to be successful in their academic pursuits and achieve graduation. Building upon that premise, California State University then identified the role that faculty played in providing a safe, warm, and nurturing learning environment, both in the didactic and clinical settings (Gardner, 2005b). This project developed several support services that students could access. For example, the position of Retention Coordinator was developed to check in with students frequently and offer support and resources. A Minority Pre-Nursing Student Outreach Committee was developed to communicate with minority students considering the nursing profession. Also created was a Family Night to bring together students, their spouses, and significant others at a monthly potluck dinner to foster a sense of connectedness and belonging. Students experiencing language barriers could be involved in a Language Partnership, which paired students with mentors who were proficient in speaking the student’s language. During the academic year 2003–2004, California State University experienced a 100% retention success for their nursing students (Gardner, 2005b). Support for EAL students was provided at one historically black university in the form of language, academic, faculty, and social activities to enhance student ability to be successful in nursing school (Brown, 2008). Preliminary results of the program indicated increased retention of EAL students along with higher scores in standardized exit and first-time NCLEX exam scores and improved perceptions of climate (Brown, 2008). The NLN’s Core Competencies for Nurse Educators (Competency 2) states that educators must facilitate current student development and socialization by identifying individual learning style preferences and the unique learning needs of students who are culturally diverse (including international), traditional versus nontraditional, and at risk (e.g., educationally disadvantaged, learning and/or physically challenged, experiencing social and economic issues) (Finke, 2009; Kalb, 2008; NLN, 2005). Given the significant shortage of nurse faculty and increasing class sizes, nurse educators are challenged to identify learning style preferences and develop appropriate learning experiences that will meet the complex needs of the current nursing student (Fountain & Alfred, 2009; Ironside & Valiga, 2006). Learning style preferences should be identified early in the undergraduate nursing curriculum with the intent to empower individual students to use their knowledge of learning style preferences in order to achieve positive outcomes (Holstein, Zangrilli, & Taboas, 2006), especially in large classes where students at risk may go unnoticed. As a group, underrepresented minority students have diverse learning style preferences (Hassouneh, 2008). Since a diverse environment is central to the mission and the academic goals of many institutions, strategies that maximize the potential for success of all students need to be tailored to fit each individual’s learning style preferences (Evans, 2008). Acknowledgment of diverse students’ learning style enhances the learning environment while supporting academic achievement (Choi, Lee, & Jung, 2008). Currently, obtaining knowledge of the learner and his or her characteristics is a vastly underused approach to improving teaching–learning strategies. To address this concern, faculty should understand their students’ learning style preferences (Slater, Lujan, & DiCarlo, 2007). Learning style is defined as the way individuals concentrate on, absorb, and retain new information (Dunn & Griggs, 2000). It is the manner in which a learner perceives, interacts with, and responds to the learning environment. Components of learning style are the cognitive, affective, and physiological elements, all of which may be strongly influenced by a person’s cultural background. Faculty are held responsible for assuring quality learning experiences in their courses and need to consider strategies for facilitating learning even when course enrollment increases. With the Bureau of Labor Statistics projecting the need for more than 1 million new and replacement registered nurses by 2016, nursing schools around the country are exploring creative ways to increase student capacity and reach out to new student populations. The challenge inherent in these efforts is to quickly produce competent nurses while maintaining the integrity and quality of the nursing education provided (AACN, 2008). Nurse educators would be wise to determine the learning styles of the students in their nursing courses (Emerson & Records, 2008), whether in the traditional classroom or online. These data will provide evidence as to how faculty should design their courses in order to retain and maximize student success, particularly in view of large enrollments. Learning environments must be evidence-based, respectful of students’ differences, and aligned with changes in health care reform (Wellman, 2009). In programs with high numbers of adult students, there may be a larger number of students who leave the program because of family problems or job-related issues (Sauter, Johnson, & Gillespie, 2009). A further concern is that achievement gaps continue to exist for diverse students. For instance, there are lower graduation rates among institutions serving high proportions of minority, low-income, and first-generation college students. Current students are striving to reduce achievement gaps, and it is important that educators augment their efforts (Brown & Marshall, 2008). A one-size-fits-all educational accommodation is likely to stress and discomfort many students who, otherwise, might perform well if their individual uniqueness were recognized and responded to instructionally (Reese & Dunn, 2007). Students are diverse in their experiences, cultural backgrounds, and traditional versus nontraditional and at-risk status. As a result of this diversity, it is unlikely that any single teaching style would be effective for all or most students in a class of 25 or more. Although faculty vary the approaches they use, they tend to differentiate instruction for the entire class rather than for individuals (Dunn & Griggs, 2000). In a large class, where students are likely to have every learning style represented, if faculty teach in the manner they were taught, they are very likely to turn off large numbers of students (Heppner, 2007). Students may experience a difficult transition due to the loss of individuality in large classes in which they receive a lack a personal recognition. The lack of mastery of course concepts may be an outcome of the professors’ lack of awareness of how differently students in the same class actually learn. Learning style is defined as the cognitive, affective, and psychological traits that serve as relatively stable indicators of how learners perceive, interact with, and respond to the learning environment (Keefe, 1987) and individuals’ preferred ways of perceiving and processing information (Kolb, 1984). Kolb defined learning style as a student’s consistent way of responding to and using stimuli in the context of learning (Claxton & Murrell, 1987). Honey and Mumford (1992) adapted a variation on the Kolb (1984) definition. They defined learning style as a description of the attitudes and behavior that determine an individual’s preferred way of learning. Dunn, Dunn, and Price (1986) defined learning style as the way in which each learner begins to concentrate on, process, and retain new and difficult information, which is a biologically and developmentally imposed set of personal characteristics or traits. Their definition incorporated environmental, emotional, sociological, physical, and psychological preferences that affected how individuals learn new and difficult information and skills (Dunn & Dunn, 1999). Grasha (1996) defined learning styles as personal qualities that influence a student’s ability to acquire information, to interact with peers and the instructor, and otherwise to participate in learning experiences. Learning preference related to the “likes and dislikes” that an individual had for a particular sensory mode or condition for learning, including a preference for certain learning strategies (Sutcliffe, 1993). Learning style may be defined as an attribute or characteristic of an individual who interacts with instructional circumstances in such a way as to produce differential learning outcomes (Linares, 1999). Aragon, Johnson, and Shaik (2002) defined learning style as the combination of the learner’s motivation and information processing habits while engaged in the learning process and how individuals acquire information and how it is processed or acted upon once acquired (Ames, 2003).

The diverse learning needs of students

Profile of contemporary nursing students

Enrollment demographics

Different generations

Millennials or generation Y

Generation X or “baby busters”

Population

Generation X

Generation Y

Non-Hispanic, White

62%

60%

Non-Hispanic, Black

12%

14%

Non-Hispanic, Asian

6%

4%

Hispanic

18%

19%

Other

2%

3%

Men in nursing

Racial and ethnic diversity

Barriers that influence the success of racially and ethnically diverse students

Lack of faculty diversity

Lack of financial resources

Lack of rigorous academic preparation

Lack of language skills

Strategies to increase the success of racially and ethnically diverse students

Role models and mentors

Support systems

Understanding learning style preferences

Definitions of learning style

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The diverse learning needs of students

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access