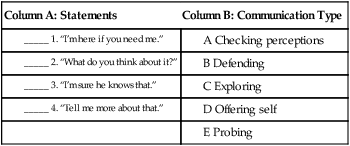

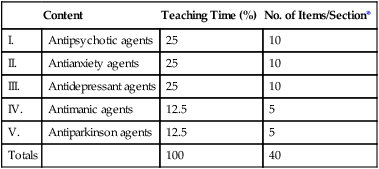

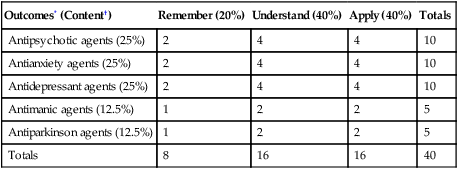

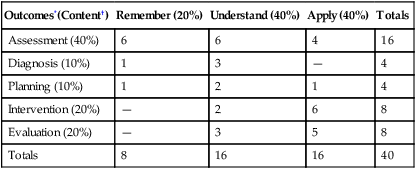

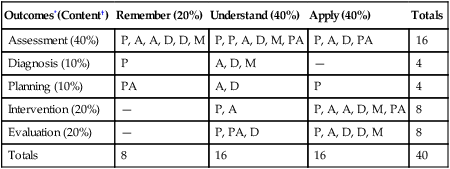

The first question that must be addressed is: “What purpose will the test serve?” If the test is to be given before instruction, it may be used to determine readiness (the grasp of prerequisite skills needed to be successful) or placement (the level of mastery of instructional objectives). During instruction, the test may be used as a formative evaluation of learning or as a diagnostic tool to identify learning problems. With the wide availability of test banks, such as those that accompany textbooks, and the ease of creating tests in a test-authoring component of a learning management system, faculty can also use tests as a way for students to practice and assess their own learning. As measures of learning outcomes, tests provide summative evaluation of learning on which progression and grading decisions may be based. See Table 26-1 for a summary of test measures based on timing of administration. Table 26-1 Test Measures Based on Timing of Administration Tests may serve a variety of additional functions. For example, testing may provide the structure (e.g., deadlines) that some students need to direct their learning activities or faculty may use testing as one means of evaluating teaching effectiveness by measuring the outcomes of student learning. Faculty may also use posttest reviews as a learning opportunity for students to discuss rationales for answers (Morrison & Free, 2001) and gain insight into their own strengths and weaknesses (Flannelly, 2001). Criterion-referenced tests are those that are constructed and interpreted according to a specific set of learning outcomes (McDonald, 2008). This type of test is useful for measuring mastery of subject matter. An absolute standard of performance is set for grading purposes. Norm-referenced tests are those that are constructed and interpreted to provide a relative ranking of students (McDonald, 2008). Norm-referenced tests are based on measurement of content according to a table of specifications (test map, test plan, test blueprint). This type of test is useful for measuring differential performance among students. A relative standard of performance is used for grading purposes. The purpose of developing a table of specifications (test map, test grid, test blueprint) is to ensure that the test serves its intended purpose by representatively sampling the intended learning outcomes and instructional content. The first step in developing a table of specifications is to define the specific learning outcomes to be measured. Specific learning outcomes, which are derived from more general instructional outcomes (e.g., course and unit objectives), specify tasks that students should be able to perform on completion of instruction (Miller, Linn, & Gronlund, 2009). Bloom’s taxonomy (1956) has been used as a guide for developing and leveling general instructional and specific learning outcomes (see Chapter 11 for details). Although the cognitive components of the affective and psychomotor domains can be evaluated with classroom tests, tests have most often been used to determine achievement of outcomes in the six levels of Bloom’s cognitive domain (Table 26-2). Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) have revised Bloom’s taxonomy, defining knowledge dimensions and cognitive processes. The knowledge dimensions are factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive. The cognitive processes are remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating (Table 26-3). Any of the six cognitive processes may be applied to the various dimensions of knowledge. Table 26-2 Bloom’s Taxonomy with Action Verbs for the Cognitive Levels TABLE 26-3 Anderson and Krathwohl’s Taxonomy with Action Verbs for the Cognitive Processes Additional attention is being given to those cognitive processing skills used by nurses, such as critical thinking, clinical judgment, and clinical decision making (Wendt & Harmes, 2009a). Test items should address these processes as well, and a mixture of cognitive processes should be evaluated at each stage of instruction, placing an increasing emphasis (or weight) on higher-level skills. This is vital because higher-level skills are more likely to result in retention and transfer of knowledge. In addition, this will assist in preparing students for the licensing and certification examinations that test primarily at the levels of application and analysis (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2010). The second step in developing a table of specifications involves determining the instructional content to be evaluated and the weight to be assigned to each area. This can be accomplished by developing a content outline and using the amount of time spent teaching the material as an indicator for weighting (Table 26-4). TABLE 26-4 Content Outline and Relative Teaching Time *Percentage of teaching time × Total no. of items = No. of items/section. Finally, a two-way grid is developed, with content areas being listed down the left side and learning outcomes being listed across the top of the grid (Table 26-5). Each cell is assigned a number of questions according to the weighting of content and cognitive processes of learning outcomes. TABLE 26-5 Two-Way Table of Specifications *Arbitrarily determined by level of instruction. Some faculty prefer to use a three-way table of specifications. With a three-way grid, the five steps of the nursing process are listed on the left side, outcomes are listed across the top, and the number of items or specific content areas is listed within each cell. Weighting of the steps of the nursing process again depends on the level of instruction. For example, early in the instructional process, assessment and diagnosis might carry the most weight, whereas all stages may be tested equally by the end of instruction. Tables 26-6 and 26-7 are examples of three-way tables of specifications. TABLE 26-6 Three-Way Table of Specifications: Number of Items per Cell *Arbitrarily determined by level of instruction. TABLE 26-7 Three-Way Table of Specifications: Content to Be Tested per Cell* A, Antianxiety agents; D, antidepressant agents; M, antimanic agents; P, antipsychotic agents; PA, antiparkinson agents. *No. of each type of content item determined by teaching time. Alternatively, or additionally, a table of specifications can be created by using the test plan of the current licensure examination (NCLEX-RN). The NCLEX-RN tests content in four categories of client needs as follows (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2010): Items may be selection-type, providing a set of responses from which to choose, or supply-type, or a constructed response type requiring the student to provide an answer. Common selection-type items include true–false, matching, ordered-response, and multiple-choice questions. Supply-type items include fill-in-the blank (usually requiring an absolute answer derived from a mathematical calculation), short-answer, multiple-response, hotspot, and essay questions (Wendt & Kenny, 2009). The primary reason for choosing one type of item over another can be determined by answering the question: “Which type of item most directly measures the intended learning outcome?” Both selection-type and supply-type questions can be developed for all levels of the cognitive domain (Su, Osisek, Montgomery, & Pellar, 2009) and to test critical thinking, problem solving, and clinical decision-making skills. Other factors may also influence the item-type selection. For example, a large class size may prohibit the use of supply-type items because of the time required for grading. In addition to multiple-choice items with one correct answer, the NCLEX-RN uses alternative format questions, which include fill-in-the-blank questions, multiple-response questions, drag-and-drop or ordered-response questions, picture or graphic questions, as well as questions that use audio files; using video clips in test questions is under consideration (Wendt & Harmes, 2009a). Current information on the examination format can be obtained at the website for the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (www.ncsbn.org). 1. Students’ scores are influenced by guessing. By chance alone, a student could get a score of 50% on a test. 2. This item type encourages memorization of text or lectures. 3. A true–false item presents two extremes that rarely match up with the real world. 4. Marking a question “false” does not mean the student knows what is really true. 5. It is difficult to write this item type at the higher levels of cognitive processes. 1. Avoid the use of absolute terms such as “all” or “always,” which indicate that the item is false. Likewise, qualifiers such as “sometimes” or “typically” indicate that the item is true. 2. State the item in a positive, declarative sentence, as simply as possible. 3. Avoid negative and double-negative statements. 4. Keep true and false statements equal in length. 5. Randomize the true and false items so the student will not detect a pattern. 6. Write each item so it is clearly true or clearly false. 7. Credit opinions to a source if understanding of beliefs is being measured. 1. A matching item is compact so a great deal of information can be tested on a single page. 2. The items can be scored quickly and objectively. 3. Students can respond to a large number of these items because reading time is short. 4. Students are required to integrate knowledge to discover the relationship. 1. The items being matched should be homogeneous. Otherwise the student can quickly find the correct responses. 2. The entire set of matching items should be on a single page to eliminate page turning. 3. Use a larger or smaller set of responses and permit them to be used more than once or not at all. 4. Arrange items in a systematic order to make the selection process quicker. 5. State in the directions the basis of relationship for matching. 6. Place the stimulus column on the left with each item numbered and the response column on the right with each item lettered. An interpretive item requires a response based on introductory material such as a paragraph, table, chart, map, or picture (Miller, Linn, & Gronlund, 2009). The student must make a judgment about the material presented. These items are often used on nursing examinations to evaluate a student’s ability to interpret laboratory data, electrocardiogram or fetal monitor strips, or other pictorial items. The questions of the NCLEX-RN examination use charts and graphic or pictorial items that may require interpretation. 1. Keep the printed information brief and readable. 2. Phrase the question so it can be answered in either short-answer or multiple-choice format. 3. Present introductory material before the question. These questions, another example of interpretive questions, assess the test-taker’s ability to seek and use data presented on a client’s chart. The data will be presented from one or more chart “tabs”: prescriptions, history and physical, laboratory results, miscellaneous reports, imaging results, flow sheets, intake and output, medication administration record, progress notes, and vital signs. When the test is administered by computer, the test-taker will be required to search in a way that simulates search through a client’s chart or computerized patient record. The current NCLEX-RN examination includes chart and exhibit questions (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2010). 1. Tests the ability to consider which data are needed for client care. 2. Tests in higher levels of cognitive domain. 3. Requires test-takers to use data for clinical decision making. 4. Requires test-takers to interpret a set of data, for example, trend data on a vital signs record. 5. Simulates obtaining data from a client’s chart; test-takers can be timed to ascertain whether they know what data to obtain and where on a chart to find it.

Developing and using classroom tests

Planning the test

Purpose of the test

Timing

Type of Test

Measure

Before

Readiness

Prerequisite skills

Placement

Previous learning

During

Formative

Learning progress

Diagnostic

Learning problems

After

Summative

Terminal performance

Types of tests

Criterion-referenced tests

Norm-referenced tests

Table of specifications

Cognitive Level

Action Verbs

Knowledge

Define, identify, list

Comprehension

Describe, explain, summarize

Application

Apply, demonstrate, use

Analysis

Compare, contrast, differentiate

Synthesis

Construct, develop, formulate

Evaluation

Critique, evaluate, judge

Cognitive Processes

Action Verbs

Remember

Retrieve, recognize, recall

Understand

Interpret, classify, summarize, infer, compare, explain, exemplify

Apply

Execute, implement

Analyze

Differentiate, organize, attribute

Evaluate

Check, critique

Create

Generate, plan, produce, reorganize

Content

Teaching Time (%)

No. of Items/Section*

I.

Antipsychotic agents

25

10

II.

Antianxiety agents

25

10

III.

Antidepressant agents

25

10

IV.

Antimanic agents

12.5

5

V.

Antiparkinson agents

12.5

5

Totals

100

40

Outcomes* (Content†)

Remember (20%)

Understand (40%)

Apply (40%)

Totals

Antipsychotic agents (25%)

2

4

4

10

Antianxiety agents (25%)

2

4

4

10

Antidepressant agents (25%)

2

4

4

10

Antimanic agents (12.5%)

1

2

2

5

Antiparkinson agents (12.5%)

1

2

2

5

Totals

8

16

16

40

Outcomes*(Content†)

Remember (20%)

Understand (40%)

Apply (40%)

Totals

Assessment (40%)

6

6

4

16

Diagnosis (10%)

1

3

—

4

Planning (10%)

1

2

1

4

Intervention (20%)

—

2

6

8

Evaluation (20%)

—

3

5

8

Totals

8

16

16

40

Outcomes*(Content†)

Remember (20%)

Understand (40%)

Apply (40%)

Totals

Assessment (40%)

P, A, A, D, D, M

P, P, A, D, M, PA

P, A, D, PA

16

Diagnosis (10%)

P

A, D, M

—

4

Planning (10%)

PA

A, D

P

4

Intervention (20%)

—

P, A

P, A, A, D, M, PA

8

Evaluation (20%)

—

P, PA, D

P, A, D, D, M

8

Totals

8

16

16

40

Other considerations in the planning stage

Selecting item types

Writing test items

True–false items

Disadvantages

Guidelines for writing true–false items

Matching items

Advantages

Guidelines for writing matching items

Interpretive items

Definition

Guidelines for writing interpretive items

Chart and exhibit questions

Definition

Advantages

Developing and using classroom tests

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access