The Childbearing and Child-Rearing Family

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to

• Describe different family structures and their effect on family functioning.

• Differentiate between healthy and dysfunctional families.

• List internal and external coping behaviors used by families when they face a crisis.

• Compare Western cultural values with values of other cultural groups.

• Describe the effect of cultural diversity on nursing practice.

• Describe common styles of parenting that nurses may encounter.

• Explain how variables in parents and children may affect their relationship.

• Discuss the use of discipline in a child’s socialization.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

No factor influences a person as profoundly as the family. Families protect and promote a child’s growth, development, health, and well-being until the child reaches maturity. A healthy family provides children and adults with love, affection, and a sense of belonging and nurtures feelings of self-esteem and self-worth. Children need stable families to grow into happy, functioning adults. Family relationships continue to be important during adulthood. Family relationships influence, positively or negatively, people’s relationships with others. Family influence continues into the next generation as a person selects a mate, forms a new family, and often rears children.

For nurses in pediatric practice, the whole family is the patient. The nurse cares for the child in the context of a dynamic family system rather than caring for just an infant or a child. The nurse is responsible for supporting families and encouraging healthy coping patterns during periods of normal growth and development or illness.

Family-Centered Care

Family-centered maternity care and family-centered child care are integral to the comprehensive care given by maternity and pediatric nurses. Family-centered care can be defined as an innovative approach to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care that is grounded in a mutually beneficial partnership among patients, families, and health care professionals (O’Malley, Brown, & Krug, 2008). Some of the barriers to effective family-centered care are lack of skills in communication, role negotiation, and developing relationships. Other areas that interfere with the full implementation of family-centered care are lack of time, fear of losing role, and lack of support from the health care system and from other health care disciplines (Harrison, 2010). Clearly, there is a need for increased education in this area, based on evidence, to help nurses and other health care professionals implement this concept.

Family Structure

Family structures in the United States are changing. The number of families with children that are headed by a married couple has declined, and the number of single-parent families has increased. In addition, roles have changed within the family. Whereas the role of the provider was once almost exclusively assigned to the father, both parents now may be providers, and many fathers are active in nurturing and disciplining their children.

Types of Families

Families are sometimes categorized into three types: traditional, nontraditional, and high risk. Nontraditional and high-risk families often need care that differs from the care needed by traditional families. Different family structures can produce varying stressors. For example, the single-parent family has as many demands placed on it for resources, such as time and money, as the two-parent family. Only one parent, however, is able to meet these demands.

Traditional Families

Traditional families (also called nuclear families) are headed by two parents who view parenting as the major priority in their lives and whose energies may not be depleted by stressful conditions such as poverty, illness, and substance abuse. Traditional families can be single-income or dual-income families. Generally, traditional families are motivated to learn all they can about pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting (Figure 3-1). Today a family structure composed of two married parents and their children represents 66% of families with children, down 4% from the last report. Twenty-six percent of children live with one parent and 44% with no parents. The remaining percentage of children live with two parents who are not married (Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011).

Single-income families in which one parent, usually the father, is the sole provider are a minority among households in the United States. Most two-parent families depend on two incomes, either to make ends meet or to provide nonessentials that they could not afford on one income. One or both parents may travel as a work responsibility. Dependence on two incomes has created a great deal of stress on parents, subjecting them to many of the same problems that single-parent families face. For example, reliable, competent child care is a major issue that has increased the stress traditional families experience. A high consumer debt load gives them less cushion for financial setbacks such as job loss. Having the time and flexibility to attend to the requirements of both their careers and their children may be difficult for parents in these families.

Nontraditional Families

The growing number of nontraditional families, designated as “complex households” by the U.S. Census Bureau, includes single-parent families, blended families, adoptive families, unmarried couples with children, multigenerational families, and homosexual parent families (Figure 3-2).

Single-Parent Families

Millions of families are now headed by a single parent, most often the mother, who must function as homemaker and caregiver and also is often the major provider for the family’s financial needs. Factors contributing to this demographic include divorce, widowhood, and childbirth or adoption among unmarried women. Among the 26% of children who live with one parent, 23% live with their mothers (Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011).

Single parents may feel overwhelmed by the prospect of assuming all child-rearing responsibilities and may be less prepared for illness or loss of a job than two-parent families.

Blended Families

Blended families are formed when single, divorced, or widowed parents bring children from a previous union into their new relationship. Many times the couple desires children with each other, creating a contemporary family structure commonly described as “yours, mine, and ours.” These families must overcome differences in parenting styles and values to form a cohesive blended family. Differing expectations of children’s behavior and development as well as differing beliefs about discipline often cause family conflict. Financial difficulties can result if one parent is obligated to pay child support from a previous relationship. Older children may resent the introduction of a stepmother or stepfather into the family system. This can cause tension between the biologic parent, the children, and the stepmother or stepfather.

Adoptive Families

People who adopt a child may have problems that biologic parents do not face. Biologic parents have the long period of gestation and the gradual changes of pregnancy to help them adjust emotionally and socially to the birth of a child. An adoptive family, both parents and siblings, is expected to make these same adjustments suddenly when the adopted child arrives. Adoptive parents may add pressure to themselves by having an unrealistically high standard for themselves as parents. Additional issues with adoptive families include possible lack of knowledge of the child’s health history, the difficulty assimilating if the child is adopted from another country, and the question of when and how to tell the child about being adopted. Adoptive parents and biologic parents need information, support, and guidance to prepare them to care for the infant or child and maintain their own relationships.

Multigenerational Families

The multigenerational or extended family consists of members from three or more generations living under one roof. Older adult parents may live with their adult children, or in some cases adult children return to their parents’ home, either because they are unable to support themselves or because they want the additional support that the grandparents provide for the grandchildren. The latter arrangement has given rise to the term boomerang families. Extended families are vulnerable to generational conflicts and may need education and referral to counselors to prevent disintegration of the family unit.

Grandparents or other older family members, because of the inability of the parents to care for their children, now head a growing number of households with children. More than half of children who do not live with either parent live with a grandparent (Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011). The strain of raising children a second time may cause tremendous physical, financial, and emotional stress.

Same-Sex Parent Families

Families headed by same-sex parents have increasingly become more common in the United States. The children in such families may be the offspring of previous heterosexual unions, or they may be adopted children or children conceived by an artificial reproductive technique such as in vitro fertilization. The couple may face many challenges from a community that is unaccustomed to alternative lifestyles. The children’s adaptation depends on the parents’ psychological adjustment, the degree of participation and support from the absent biologic parent, and the level of community support.

Communal Families

Communal families are groups of people who have chosen to live together as extended family groups. Their relationship to one another is motivated by social value or financial necessity rather than by kinship. Their values are often spiritually based and may be more liberal than those of the traditional family. Traditional family roles may not exist in a communal family.

Characteristics of Healthy Families

In general, healthy families are able to adapt to changes that occur in the family unit. Pregnancy and parenthood create some of the most powerful changes that a family experiences.

Healthy families exhibit the following common characteristics, which provide a framework for assessing how all families function (Cooley, 2009):

• Members of healthy families communicate openly with one another to express their concerns and needs.

• Healthy families are adaptable and are not overwhelmed by life changes.

• Members of healthy families volunteer assistance without waiting to be asked.

• Family members spend time together regularly but facilitate autonomy.

• Healthy families seek appropriate resources for support when needed.

• Healthy families transmit cultural values and expectations to children.

Factors that Interfere with Family Functioning

Factors that may interfere with the family’s ability to provide for the needs of its members include lack of financial resources, absence of adequate family support, birth of an infant who needs specialized care, an ill child, unhealthy habits such as smoking and abuse of other substances, and inability to make mature decisions that are necessary to provide care for the children. Needs of aging members at the time children are going through adolescence or the expenses of college add pressure on middle-aged parents, often called the “sandwich generation.”

High-Risk Families

All families encounter stressors, but some factors add to the usual stress experienced by a family. The nurse needs to consider the additional needs of the family with a higher risk for being dysfunctional. Examples of high-risk families are those experiencing marital conflict and divorce, those with adolescent parents, those affected by violence against one or more of the family members, those involved with substance abuse, and those with a chronically ill child.

Marital Conflict and Divorce

Although divorce is traumatic to children, research has shown that living in a home filled with conflict can also be detrimental both physically and emotionally (Kelly & El-Sheikh, 2011; Lindahl & Malik, 2011). Divorce can be the outcome of many years of unresolved family conflict. It can result in continuing conflict over child custody, visitation, and child support; changes in housing, lifestyle, cultural expectations, friends, and extended family relationships; diminished self-esteem; and changes in the physical, emotional, or spiritual health of children and other family members.

Divorce is loss that needs to be grieved. The conflict and divorce may affect children, and young children may be unable to verbalize their distress. Nurses can help children through the grieving process with age-appropriate activities such as therapeutic play (see Chapter 35). Principles of active listening (see Chapter 4) are valuable for adults as well as children to help them express their feelings. Nurses can also help newly divorced or separated parents through listening, encouragement, and referrals to support groups or counselors.

Adolescent Parenting

The teenage birth rate in the United States decreased by more than one-third from 1991 through 2005 but increased by 5% over the next 2 years. Current data show another downward trend, reaching a historic low of 39.1 per 1000 teen births. Adolescent birth rates vary by race; however, there has been a steady decline in teen birth rates for all racial and ethnic groups. The birth rate for Hispanic teenagers showed the largest decline of all race and ethnicity groups. From 2008 to 2009, the rate declined by 11% (National Center for Health Statistics, 2011).

Teenage parenting often has a negative effect on the health and social outcomes of the entire family. Adolescent girls are at increased risk for a number of pregnancy complications, such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and death during infancy (Ventura & Hamilton, 2011). Those who become parents during adolescence are unlikely to attain a high level of education and, as a result, are more likely to be poor and often homeless. An adolescent father often does not contribute to the economic or psychological support of his child. Moreover, the cycle of teen parenting and economic hardship is more likely to be continued because children of adolescent parents are themselves more likely to become teenage parents.

Violence

Violence is a constant stressor in some families. Violence can occur in any family of any socioeconomic or educational status. Children endure the psychological pain of seeing their mother victimized by the man who is supposed to love and care for her (see Chapter 24). In addition, because of the role models they see in the adults, children in violent families may repeat the cycle of violence when they are adults and become abusers or victims of violence themselves.

Abuse of the child may be physical, sexual, or emotional or may take the form of neglect (see Chapter 53). Often one child in the family is the target of abuse or neglect, whereas others are given proper care. As in adult abuse, children who witness abuse are more likely to repeat that behavior when they are parents themselves, because they have not learned constructive ways to deal with stress or to discipline children.

Substance Abuse

Parents who abuse drugs or alcohol may neglect their children because obtaining and using the substance(s) may have a stronger pull on the parents than does care of their children. Parental substance abuse interrupts a child’s normal growth and development. The parent’s ability to meet the needs of the child are severely compromised, increasing the child’s risk for emotional and health problems (Children of Alcoholics Foundation, 2011).

The child may be the substance abuser in the home. The drug habit can lead a child into unhealthy friendships and may result in criminal activity to maintain the habit. School achievement is likely to plummet, and the older adolescent may drop out of school. Children, as well as adults, can die as a result of their drug activity, either directly from the drugs or from associated criminal activity or risk-taking behaviors.

Child with Special Needs

When a child is born with a birth defect or has an illness that requires special care, the family is under additional stress (see Chapters 36 and 54). In most cases their initial reactions of shock and disbelief gradually resolve into acceptance of the child’s limitations. However, the parents’ grieving may be long term as they repeatedly see other children doing things that their child cannot and perhaps will not ever do.

These families often suffer financial hardship. Health insurance benefits may quickly reach their maximum. Even if the child has public assistance for health care costs, the family often experiences a decrease in income because one parent must remain home with the sick child rather than work outside the home.

Strains on the marriage and the parents’ relationships with their other children are inevitable under these circumstances. Parents have little time or energy left to nurture their relationship with each other, and divorce may add yet another strain to the family. Siblings may resent the parental time and attention required for care of the ill child yet feel guilty if they express their resentment.

The outlook is not always pessimistic in these families, however. If the family learns skills to cope with the added demands imposed on it by this situation, the potential exists for growth in maturity, compassion, and strength of character.

Healthy Versus Dysfunctional Families

Family conflict is unavoidable. It is a natural result of a perceived unequal exchange or an imbalance in the use of resources by individual members. Conflict should not be viewed as bad or disruptive; the management of the conflict, not the conflict itself, may be problematic. Conflict can produce growth and improve family functioning if the outcome is resolution as opposed to dissolution or continued conflict. The following three ingredients are required to resolve conflict:

Dysfunctional families have problems in any one or a combination of these areas. They tend to become trapped in patterns in which they maintain conflicts rather than resolve them. The conflicts create stress, and the family must cope with the resultant stress.

Coping with Stress

If the family is considered a balanced system that has internal and external interrelationships, stressors are viewed as forces that change the balance in the system. Stressful events are neither positive nor negative, but rather neutral until they are interpreted by the individual. Positive, as well as negative, events can cause stress (Smith et al., 2009). For example, the birth of a child is usually a joyful event, but it can also be stressful.

Some families are able to mobilize their strengths and resources, thus effectively adapting to the stressors. Other families fall apart. A family crisis is a state or period of disorganization that affects the foundation of the family (Smith et al., 2009).

Coping Strategies

Nurses can help families cope with stress by helping each family identify its strengths and resources. Friedman, Bowden, and Jones (2003) identified family coping strategies as internal and external. Box 3-1 identifies family coping strategies and further defines internal strategies as family relationship strategies, cognitive strategies, and communication strategies. External strategies focus on maintaining active community linkages and using social support systems and spiritual strategies. Some families adjust quickly to extreme crises, whereas other families become chaotic with relatively minor crises. Family functional patterns that existed before a crisis are probably the best indicators of how the family will respond to it.

Cultural Influences on Maternity and Pediatric Nursing

Culture is the sum of the beliefs and values that are learned, shared, and transmitted from generation to generation by a particular group. Cultural values guide the thinking, decisions, and actions of the group, particularly regarding pivotal events such as birth, sexual maturity, illness and death. Ethnicity is the condition of belonging to a particular group that shares race, language and dialect, religious faiths, traditions, values, and symbols as well as food preferences, literature, and folklore. Cultural beliefs and values vary among different groups and subgroups, and nurses must be aware that individuals often believe their cultural values and patterns of behavior are superior to those of other groups. This belief, termed ethnocentrism, forms the basis for many conflicts that occur when people from different cultural groups have frequent contact.

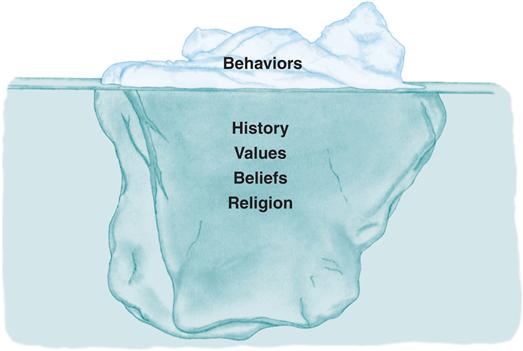

Nurses must be aware that culture is composed of visible and invisible layers that could be said to resemble an iceberg (Figure 3-3). The observable behaviors can be compared with the visible tip of the iceberg. The history, traditions, beliefs, values, and religion are not necessarily observed but are the hidden foundation on which behaviors are based and can be likened to the large, submerged part of the iceberg. To comprehend cultural behavior fully, one must seek knowledge of the hidden beliefs that behaviors express. This knowledge comes from experiencing caring relationships with people of different cultures within the context of mutual respect and a sincere desire to understand the role of culture in another’s “lived experiences” (Bearskin, 2011). One must also have the desire or motivation to engage in the process of becoming culturally competent in order to be effective in caring for diverse populations.

Nurses must first understand their own culture and recognize their biases before beginning to acquire the knowledge and understanding of other cultures. Applying the knowledge completes the process (Galanti, 2008).

Religious and spiritual beliefs often have a strong influence on families as they face the crisis of illness. Specific beliefs about the causes, treatment, and cure of illness are important for the nurse to know to empower the family as they deal with the immediate crisis. Table 3-1 describes how some religious beliefs affect health care.

TABLE 3-1

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AFFECTING HEALTH CARE

| RELIGION AND BASIC BELIEFS | PRACTICES |

| Christianity | |

| Christianity is generally accepted to be the largest religious group in the world. There are three major branches of Christianity and a number of religious traditions considered to be Christian. These traditions have much in common relative to beliefs and practices. Belief in Jesus Christ as the son of God and the Messiah comprises the central core of Christianity. Christians believe that it is through Jesus’ death and resurrection that salvation can be attained. They also believe that they are expected to follow the example of Jesus in daily living. Study of biblical scripture; practicing faith, good works, and sacramental rites (e.g., baptism, communion, and others); and prayer are common among most Christian faiths. | |

| Christian Science | |

| Based on scientific system of healing. Beliefs derived from both the Bible and the book, Science, and Health with Key to the Scriptures. Prayer is the basis for spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental healing, as opposed to medical intervention (Christian Science, 2011). Healing is divinely natural, not miraculous. | Birth: Use physician or midwife during childbirth. No baptism ceremony. Dietary practices: Alcohol and tobacco are considered drugs and are not used. Coffee and tea also may be declined. Death: Autopsy and donation of organs are usually declined. Health care: May refuse medical treatment. View health in a spiritual framework. Seek exemption from immunizations but obey legal requirements. When Christian Science believer is hospitalized, parent or client may request that a Christian Science practitioner be notified. |

| Jehovah’s Witness | |

| Expected to preach house to house about the good news of God. Bible is doctrinal authority. No distinction is made between clergy and laity. | Baptism: No infant baptism. Adult baptism by immersion. Dietary practices: Use of tobacco and alcohol discouraged. Death: Autopsy decided by persons involved. Burial and cremation acceptable. Birth control and abortion: Use of birth control is a personal decision. Abortion opposed on basis of Exodus 21:22-23. Health care: Blood transfusions not allowed. May accept alternatives to transfusions, such as use of non-blood plasma expanders, careful surgical technique to minimize blood loss, and use of autologous transfusions. Nurses should check an unconscious patient for identification that states that the person does not want a transfusion. Jehovah’s Witnesses are prepared to die rather than break God’s law. Respect the health care given by physicians, but look to God and His laws as the final authority for their decisions. |

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormon) | |

| Restorationism: True church of Christ ended with the first generation of apostles but was restored with the founding of Mormon Church. Articles of faith: Mormon doctrine states that individuals are saved if they are obedient to God’s divine ordinances (faith, repentance, baptism by immersion and laying on of hands). Holy Communion: Hospitalized patient may desire to have a member of the church’s clergy administer the sacrament. Scripture: Word of God can be found in the Bible, Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, Pearl of Great Price, and current revelations. Christ will return to rule in Zion, located in America. | Baptism: By immersion. Considered essential for the living and the dead. If a child older than 8 years is very ill, whether baptized or unbaptized, a member of the church’s clergy should be called. Anointing of the sick: Mormons frequently are anointed and given a blessing before going to the hospital and after admission by laying on of hands. Dietary practices: Tobacco and caffeine are not used. Mormons eat meat (limited) but encourage the intake of fruits, grains, and herbs. Death: Prefer burial of the body. A church elder should be notified to assist the family. Birth control and abortion: Abortion is opposed unless the life of the mother is in danger. Only natural methods of birth control are recommended. Other means are used only when the physical or emotional health of the mother is at stake. Other practices: Believe in the healing power of laying on of hands. Cleanliness is important. Believe in healthy living and adhere to health care requirements. Families are of great importance, so visiting should be encouraged. The church maintains a welfare system to assist those in need. |

| Roman Catholicism | |

| Belief that the Word of God is handed down to successive generations through scripture and tradition, and is interpreted by the magisterium (the Pope and bishops). Pope has final doctrinal authority for followers of the Catholic faith, which includes interpreting important doctrinal issues related to personal practice and health care. | Baptism: Infant baptism by affusion (sprinkling of water on head) or total immersion. Original sin is believed to be “washed away.” If death is imminent or a fetus is aborted, anyone can perform the baptism by sprinkling water on the forehead, saying “I baptize thee in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” Anointing of the Sick: Encouraged for anyone who is ill or injured. Always done if prognosis is poor. Dietary practices: Fasting and abstinence from meat optional during Lent. Fasting required for all, except children, elders, and those who are ill, on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. Avoidance of meat on Ash Wednesday and on Fridays during Lent strongly encouraged. Death: Organ donation permitted. |

| Amish | |

| Christians who practice their religion and beliefs within the context of strong community ties. Focused on salvation and a happy life after death. Powerful bishops make health care decisions for the community. Problems solved with prayer and discussion. Primarily agrarian; eschew many modern conveniences. | Baptism: Late teen/early adult. Must marry within the church. Death: Do not normally use extraordinary measures to prolong life. Other practices: May have a language issue (modified German or Dutch) and need an interpreter. At increased risk for genetic disorders; refuse contraception or prenatal testing. May appear stoical or impassive—personally humble. Reject health insurance; rely on the Church and community to pay for health care needs. Use holistic and herbal remedies, but accept western medical approaches. |

| Hinduism | |

| Belief in reincarnation and that the soul persists even though the body changes, dies, and is reborn. Salvation occurs when the cycle of death and reincarnation ends. Nonviolent approach to living. Congregation worship is not customary; worship is through private shrines in the home. Disease is viewed holistically, but Karma (cause and effect) may be blamed. | Circumcision is observed by ritual. Dietary practices: Dietary restrictions vary according to sect; vegetarianism is not uncommon. Death: Death rituals specify practices and who can touch corpse. Family must be consulted, as family members often provide ritualistic care. Other practices: May use ayurvedic medicine—an approach to restoring balance through herbal and other remedies. Same-sex health providers may be requested. |

| Islam | |

| Belief in one God that humans can approach directly in prayer. Based on the teachings of Muhammad. Five Pillars of Islam. Compulsory prayers are said at dawn, noon, afternoon, after sunset, and after nightfall. | Dietary practices: Prohibit eating pork and using alcohol. Fast during Ramadan (ninth month of Muslim year). Death: Oppose autopsy and organ donation. Death ritual prescribes the handling of corpse by only family and friends. Burial occurs as soon as possible. |

| Judaism | |

| Beliefs are based on the Old Testament, the Torah, and the Talmud, the oral and written laws of faith. Belief in one God who is approached directly. Believe Messiah is still to come. Believe Jews are God’s chosen people. | Circumcision: A symbol of God’s covenant with Israel. Done on eighth day after birth. Bar Mitzvah/Bat Mitzvah: Ceremonial rite of passage for boys and girls into adulthood and taking personal responsibility for adherence to Jewish laws and rituals. Death: Remains are washed according to Jewish rite by members of a group called the Chevra Kadisha. This group of men and women prepare the body for burial and protect it until burial occurs. Burial occurs as soon as possible after death. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree