The Child with a Sensory Alteration

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

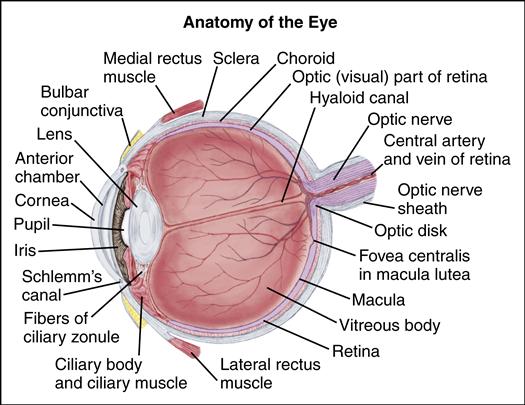

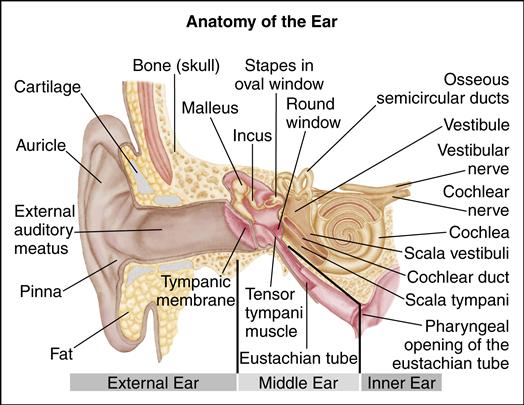

• Describe the structure and function of the eye and ear.

• Define the nurse’s role in assessing for sensory alterations.

• Describe specific nursing care for children with health problems affecting the eye and ear.

• Describe how alterations in the sensory organs affect the child’s ability to communicate.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Because a child learns so much through the senses, deficits in hearing and vision can have profound effects on development. Appropriate screening and early interventions are crucial. Early identification of vision and hearing deficits allows for early intervention—either correction or the provision of adaptive measures—so that the child’s “normal” growth and development may be preserved. Because a child cannot report sensory deficits, nurses must carefully assess for alterations in vision or hearing.

U.S. legislation PL 94-142 (Education for All Handicapped Children Act) was passed in 1975 and subsequently updated as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (see Chapter 54); it mandates special education services for children with severe sensory deficits. The identification of children who might be eligible for special educational services at a young age is important so that their education can be maximized.

The health history of a child with a potential sensory deficit is essentially the same as for any child (see Chapter 33) but should include the following additional pieces of information:

• Growth and developmental history

• History of any infections (including treatment, because many medications can cause sensory deficits)

• Previous trauma to the eye or ear

• Changes in appearance (e.g., red, inflamed eyes; drainage from the eye or ear)

• Physical symptoms (e.g., reports of ear or eye pain, headache, nausea, and vomiting)

After carefully reviewing the health history, the nurse performs a thorough physical examination with age-appropriate measures of vision and hearing acuity (see Chapter 33).

Disorders of the Eye

The nurse has an important role in the prevention and early detection of eye problems. All children should have sensitive and specific vision screening performed at well visits. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Academy of Ophthalmology, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and Children’s Eye Foundation (Donahue & Ruben, 2011) recommend the following:

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2011), along with the previously mentioned organizations (Donahue & Ruben, 2011) recommend the following for older children:

Age 3 years and older: All of the above plus visual acuity using developmentally appropriate charts (HOTV matching test, Lea symbols, “tumbling E”) and ophthalmoscopy; stereopsis can be tested by using the random dot E test (see Chapter 33). For children who are uncooperative or who are otherwise unable to participate in traditional vision screening, photoscreening or autorefraction may be used. Photoscreening (photo refractive screening), a process of photographing images of eye light reflexes, can easily detect a variety of eye problems in young children. Photoscreening is particularly useful for detecting refractive errors, strabismus, and other conditions that contribute to amblyopia (USPSTF, 2011). Autorefraction is the process for estimating refractive error in order to predict actual refractive problems in children (Children’s Eye Foundation, 2011). Through use of equipment that uses ultrasound measurements, refracted error can be estimated (Children’s Eye Foundation, 2011). Refer children who do not pass structural or vision screening for complete ophthalmologic evaluation. Careful attention to behavior and appearance changes, as well as physical symptoms, assists in the early detection and treatment of eye disorders (Box 55-1). Children who have any symptoms should be referred for further evaluation.

Nursing Considerations for the Child with Color Deficiency

Colorblindness, or color deficiency, occurs in approximately 8% of the population and primarily affects males. It interferes with the ability to distinguish between colors within certain groups, such as red, blue, and green.

Testing should be done if the clinician suspects a problem (i.e., a suspected optic nerve or retinal dysfunction) or the family has a history of color deficiency. Testing is routine in preschool boys. The most common detection test is the pseudoisochromatic (color confusion) test, in which color plates include patterns that are hidden to a person with a color deficit. Pseudoisochromatic plates are also available for children who cannot yet read. If a problem is detected, more sophisticated testing may be necessary to determine the exact type of color deficiency. Although color deficiency has no cure, certain types of tints used in contact lenses and glasses can help the child discriminate color differences.

Because color deficiency cannot be cured, nursing care focuses on adaptive and supportive measures. Encourage parents to have children tested if the family has a history of color deficiency or if the nurse suspects the child is having trouble distinguishing colors.

Parent and child education is important for the child with color deficiency. Teaching should focus on alternative ways to discriminate the deficient colors. For the older child who can dress without assistance, clothes can be labeled or organized so that items can be easily coordinated.

Safety is a major concern for the color-deficient child. For example, the child who cannot distinguish red and green must learn another way to distinguish traffic signals and other warning lights. Finally, anticipatory guidance is sometimes related to appropriate career choices. For example, color deficiency might prohibit an adult from becoming a pilot, police officer, or firefighter.

Nursing Considerations for the Child with a Blocked Lacrimal Duct

A blocked lacrimal (tear) duct is characterized by excessive tearing (epiphora) and crusting on the eyelids on awakening. Parents may also note a small mass just below the inner aspect of the eye. Treatment usually consists of massaging the duct. If the duct remains blocked despite massaging or remains blocked after 1 year of age, surgical opening of the duct is indicated.

The nurse should carefully assess the mucoid drainage. In a noninfected duct, the drainage is usually white or clear. If the duct has become infected, however, the drainage may be green or yellow. If the drainage suggests an infected duct, treatment with antibiotic eyedrops or ointment is indicated.

The nurse teaches the parent about the proper technique for lacrimal massage. This process involves washing hands thoroughly and placing the index finger over the lacrimal duct (at the inner aspect of the eye by the bridge of the nose) and “milking,” or gently massaging, the duct in an upward motion. Emphasize that massaging down the nasal bone has very little effect on the duct because the lacrimal system is intraosseous and unaffected by massage over bone. Other teaching includes monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection.

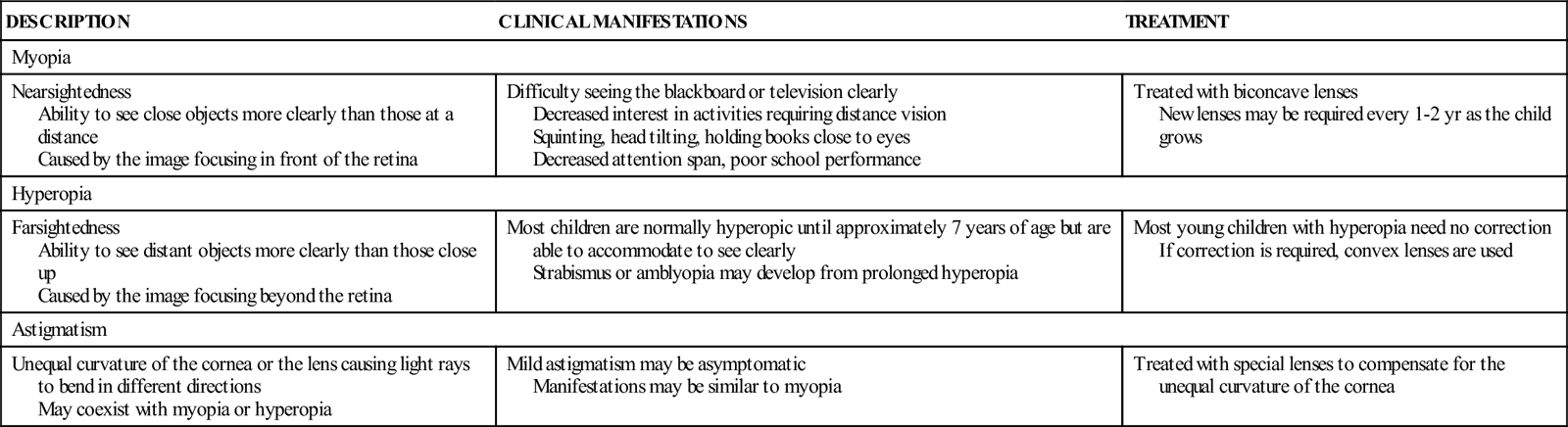

Nursing Considerations for the Child with a Refractive Error

Refractive errors cause vision disturbances from alterations in the path of light rays through the eye. They usually result from an abnormally shaped orb; the orb may be flattened or elongated (Table 55-1). Refractive errors are often discovered when a child squints, frowns, or moves objects so they are more easily seen. Reports from the child or a teacher may also alert parents. Legal blindness is defined as a correction of 20/200 or worse in the better eye or a visual field of 20 degrees or less.

TABLE 55-1

| DESCRIPTION | CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS | TREATMENT |

| Myopia | ||

| Nearsightedness Ability to see close objects more clearly than those at a distance Caused by the image focusing in front of the retina | Difficulty seeing the blackboard or television clearly Decreased interest in activities requiring distance vision Squinting, head tilting, holding books close to eyes Decreased attention span, poor school performance | Treated with biconcave lenses New lenses may be required every 1-2 yr as the child grows |

| Hyperopia | ||

| Farsightedness Ability to see distant objects more clearly than those close up Caused by the image focusing beyond the retina | Most children are normally hyperopic until approximately 7 years of age but are able to accommodate to see clearly Strabismus or amblyopia may develop from prolonged hyperopia | Most young children with hyperopia need no correction If correction is required, convex lenses are used |

| Astigmatism | ||

| Unequal curvature of the cornea or the lens causing light rays to bend in different directions May coexist with myopia or hyperopia | Mild astigmatism may be asymptomatic Manifestations may be similar to myopia | Treated with special lenses to compensate for the unequal curvature of the cornea |

Nurses should assess children’s vision at every well-child visit, particularly during the preschool years. Visual acuity can be reliably tested in a cooperative child as young as 3 years. When testing visual acuity, the nurse needs to remember that a vision discrepancy of two lines or more on the vision chart, even if one eye tests normal, is cause for referral. A child with this discrepancy could have anisometropia, or a large refractive discrepancy between eyes. If not corrected, this condition can lead to amblyopia.

School nurses routinely test children’s vision and, in fact, annual vision screening is offered to children throughout the United States. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2011) has recommended that vision screening begin early in the preschool years (at 3 years of age) to identify amblyopia and other associated vision alterations Several states in the United States mandate that a child have an approved vision screening test (administered by a trained examiner) within the year prior to entering kindergarten. The HOTV matching test, Lea symbols, and the “tumbling E” test are comparatively effective as screening measures for preschool age children (Chou, Dana, & Bougatsos, 2011). Evidence suggests that vision screening tests, which can include photoscreening or autorefraction testing, can accurately identify vision problems in young children (Chou et al., 2011). School nurses have used various methods of notifying families of children who do not pass a school vision screening (e.g., telephone call to parents, letter brought home by the child, letter mailed home). However, the parent is responsible for follow-through with a visit to a specialist. Nurses need to be aware that some parents, for a variety of reasons, do not take the child for a follow-up comprehensive eye examination; for this reason, nurses in other settings must ask for details about the child’s vision and previous vision testing.

Corrective lenses are used to improve the child’s vision. Encourage the parent to look for impact-resistant eyeglasses with spring-loaded frames, which are less likely to bend or warp. Fitting glasses to an infant or young child can be challenging; the goal is to choose shatter-resistant lenses in a type of frame that can be closely fitted to prevent easy dislodging during activity. Infant frames often have elasticized straps to keep them properly positioned. Teach the parent, and child if appropriate, to always store the glasses in a case when not being used. Special directions for cleaning must be followed to avoid scratching the lenses.

Both gas-permeable and soft contact lenses provide an alternative for children old enough and responsible enough to care for contacts independently. The nurse needs to teach parents and children about appropriate care of corrective lenses and should educate parents and children about recognizing and intervening with vision problems early.

Protective eyewear made of shatterproof polycarbonate, should be worn by all who participate in sports that have risk for eye injury. A variety of prescription sports glasses are available for athletes. Protective eyewear should be selected according to the sport and the relative risk for injury (American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2011).

Nursing Considerations for the Child with Amblyopia

Amblyopia, or “lazy eye,” one of the most common causes of diminished vision in children, results from a variety of eye alterations seen in children whose visual acuity is impaired. Various reports state that the prevalence of amblyopia is between 2% and 4% of children (USPSTF, 2011).When both eyes are unable to focus simultaneously, the brain suppresses the image from the deviating eye to avoid double vision (diplopia). Amblyopia frequently accompanies strabismus, as well as other eye conditions such as congenital cataract and severe refractive error. If the underlying eye condition is untreated in a child younger than 4 years (the critical period for development of the visual cortex), permanent loss of vision from amblyopia can result; amblyopia can be treated in the older child, but it is more resistant to treatment approaches at that time (Olitsky, Hug, Plummer, et al., 2011). Because the child loses binocular vision, depth perception may also be impaired. Early detection and treatment of strabismus or other underlying causes of amblyopia are essential to prevent loss of vision.

Two primary approaches, penalization (blurring) and occlusion, are used to correct amblyopia, and each is designed to alter or obscure vision in the stronger eye to force the child to use the amblyopic eye. Atropine, which is a cycloplegic (paralyzes the ciliary muscles to dilate the eye), most often is used to blur the vision in the stronger eye. Wearing eyeglasses in which the lens over the stronger eye creates blurring has a similar effect (Doshi & Rodriguez, 2007).

Wearing lenses corrective for refraction error can improve amblyopia in some children (Stewart, Moseley, & Fielder, 2011). Patching, combined with use of corrective lenses, has been demonstrated to have better outcomes than wearing corrective lenses alone for treatment of amblyopia caused by strabismus (Taylor & Elliott, 2011). Patching is used primarily to correct amblyopia and is used mostly during the preschool years when the visual cortex is developing. In this treatment, the normal eye is patched so that the child is forced to use the weaker eye. The schedule for patching is individualized. Recent evidence suggests that some children will respond well to a patching regimen that does not require 24 hour occlusion, but as little as 2 to 4 hours of daily use (Olitsky et al., 2011; Stewart et al., 2011). The patching regimen is prescribed by the ophthalmologist. Cooperation with the patching regimen is essential. Teaching should explain the reasons for patching or corrective lenses, the expected results of wearing the patch or lens, correct placement of the patch, the number of hours per day the patch or lens is to be worn, and the expected length of treatment (see Patient-Centered Teaching: Information about Eye Patching). The child needs to understand that wearing the patch or lens is not negotiable. The nurse often must teach parents strategies for dealing with resistant behaviors.

Nursing Considerations for the Child with Strabismus

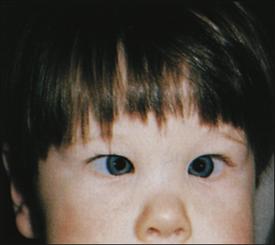

Strabismus is a condition in which the eyes are not aligned because of lack of coordination of the extraocular muscles. It is present in approximately 4% of children younger than 6 years

(Olitsky et al., 2011). Strabismus is most often caused by muscle imbalance or paralysis of the extraocular muscles but may also result from conditions such as a brain tumor, myasthenia gravis, or infection. Infants and children with strabismus often have a close relative with the condition. Other contributing factors include genetic abnormalities, neuromuscular disease, exposure to teratogens, and trauma; the prevalence is higher in children who were born prematurely or who were of low birth weight (Pathai, Cumberland, & Rahi, 2010). The type of deviation noted defines strabismus (Box 55-2). When assessing infants for strabismus, the nurse needs to remember that strabismus is normal in the young infant but should not be present after approximately 3 months of age.

The corneal light reflex test, simultaneous red reflex test, cover-uncover test, and alternate-cover test (see Chapter 33) are used in the diagnosis of strabismus. The nurse may suspect strabismus when the child reports frequent headaches, squints, or tilts the head to see. The parent may suspect something is wrong when a flash photograph of the child reveals unequal “red eye.” Children who have family members with strabismus should be regularly assessed for development of the condition. Strabismus can contribute to amblyopia in the infant or young child.

Treatment of strabismus may include special corrective lenses, vision therapy, surgery, or pharmacologic therapy. If the deviation is caused by hyperopia, corrective lenses are indicated to correct vision. Eyeglasses with specially ground prism power may also be indicated. These glasses correct vision in the affected eye so that the brain receives the same image from both eyes.

Botulinum toxin (Botox) was approved in 1989 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as an alternative to surgery in some cases. The toxin is injected into the eye muscle and produces temporary paralysis. This condition allows the muscles opposite the paralyzed muscle to straighten the eye. With successful treatment, the correction remains after the medication wears off (in approximately 2 months). The most common side effect is a drooping eyelid (ptosis), which usually resolves spontaneously.

Surgery may be indicated to realign the weakened muscles in a child with strabismus. It is most often indicated when amblyopia is present and should be performed before the child is 2 years of age. The stronger eye may be patched before surgery to treat any existing amblyopia. Surgery may be required only on the weakened eye or on both eyes. More than one surgery may be necessary. During the surgery, small incisions are made and the weakened muscles are tightened or the stronger muscles are weakened and lengthened (Modi & Jones, 2008).

If the child is to have a surgical correction, the nurse should prepare the child and parents before surgery for what to expect after surgery and provide information about dressing changes, eyedrops, corrective lenses, and any other postoperative treatments that may be required. Interventions are similar to those for any child having eye surgery (see pp.1507-1508).

Nursing Considerations for the Child with Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a condition in which the intraocular fluid pressure of the eye is increased. This pressure increase, if left untreated, leads to atrophy of the optic disk and, ultimately, blindness. Glaucoma is a significant cause of blindness in children (Aponte, Diehl, & Mohney, 2010).

Several types of glaucoma occur in children. Congenital glaucoma and infantile glaucoma occur during the first 3 years of life and are caused by a defect in the drainage network of the eye. Primary congenital glaucoma has a genetic origin, with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Secondary glaucoma, which may be associated with other ocular anomalies, refers to disease that occurs after 3 years of age and may be the result of inherited disease (juvenile glaucoma) or may be acquired from infection, trauma, or cataract removal (acquired glaucoma) (Olitsky et al., 2011).

Clinical signs of glaucoma include excessive tearing, light sensitivity, blepharospasm (muscle spasm causing involuntary closing of the eyelid), and enlargement of the globe and cornea. Parents often note excessive tearing or corneal haziness caused by edema and bring the child in for clinical evaluation. The child may also be brought to the practitioner for what appears to be conjunctivitis (“pink eye”).

Physical examination includes an assessment of visual acuity, measurement of intraocular pressure (tonometry), assessment of corneal diameter and clarity, and an examination of the retina to assess for optic nerve cupping. Any infant with a visible iris diameter greater than 10.5 mm should be evaluated. If retinal edema is present, the light reflex is diffuse. Because young children may not be able to cooperate during an examination, they are often sedated. Intraocular pressure should be measured only under light sedation, however, because deeper sedation may alter readings (either high or low, depending on the agent used).

The preferred treatment for childhood glaucoma is surgery. Medications to clear the cornea may be used before surgery to allow better visibility. Surgery should be performed as soon as possible after diagnosis to prevent loss (or further loss) of vision. The goals of surgery are to increase the outflow of the aqueous humor from the anterior chamber by correcting the structural abnormality that is causing the decreased outflow, create a different route for the outflow (trabeculotomy), or decrease production of aqueous fluid (Olitsky et al., 2011). Medications such as cholinergic agents, beta-adrenergic blocking agents, or adrenergic agents may be indicated after surgery to maintain low intraocular pressure.

Prognosis varies from child to child. The earlier the glaucoma develops, the poorer the prognosis, because infants and children with early onset glaucoma usually have defects in the development of the anterior chamber of the eye that occurred during fetal development (Olitsky et al., 2011). In general, with prompt treatment most children attain appropriate vision. Decreased vision may result from damage to the optic nerve, opacity of the cornea or lens, or amblyopia resulting from refractive errors. Children with glaucoma must be followed closely over the long term to identify any rise in intraocular pressure quickly.

Nursing interventions are similar to those for any child having eye surgery. Postoperative nursing care includes monitoring for signs and symptoms of increased intraocular pressure (pain, nausea and vomiting, increased inflammation) and administering any ordered medications, such as miotic eyedrops (used to constrict the pupils) and antibiotic ointments or eyedrops. If the child’s eyes are patched, the nurse pays special attention to the resulting sensory deficits. The nurse also considers safety to be an issue when eyes are patched.

Parental education is essential to maintain the appropriate intraocular pressure and prevent complications (including blindness). Education includes the use of any prescribed medications, patching, and any other measures designed to correct refractive errors. The importance of returning for follow-up care should be emphasized. The child and caregivers should also be taught signs and symptoms of increasing intraocular pressure. Any signs of increasing intraocular pressure or infection should be immediately reported to the ophthalmologist. Because certain types of glaucoma can be related to genetic abnormalities, referral for genetic counseling may be indicated.

Nursing Considerations for the Child with a Cataract

A cataract is an opacity, or loss of transparency, of the lens. Causes include an inherited tendency (usually an autosomal dominant trait), infection (e.g., rubella), trauma, or a metabolic imbalance; the cause of congenital cataracts is unknown (Davenport & Patel, 2011). Cloudiness of the lens may be noted during examination in the newborn nursery (indicated by a white instead of red reflex) or by the parents. Ophthalmoscopy may reveal a dark spot in the lens. Parents may note that the infant exhibits visual inattentiveness and come in for an evaluation. Other clinical signs include nystagmus and strabismus. The cataract alters vision because it does not allow a sharp, clear image to be formed on the retina.

Treatment for cataracts in most instances is the surgical removal of the opaque lens as soon as possible and optimally within 6 to 10 weeks of age (Davenport & Patel, 2011). The resultant hyperopia is then dealt with by using a contact lens or, in older children, an intraocular lens implant. Any resulting amblyopia must also be addressed. Glasses may also be used to correct the resultant vision problem, although these may be difficult to manage in infants and small children (Olitsky et al., 2011).

Amblyopia may be a consequence of congenital cataract. In this case, the normal eye may be patched after surgery to develop the weakened eye.

Postoperative interventions are directed toward avoiding increased intraocular pressure. Measures include preventing coughing, straining, vomiting, and touching the operative site. A patch and “hard shield” are usually in place after surgery to prevent injury to the operative site. To prevent edema and pressure on the site, the nurse should elevate the head of the bed slightly and position the child so that the affected eye is not in a dependent position. Monitor the child for signs and symptoms of infection (fever, drainage, redness). Medications, including antibiotics, mydriatics, and steroids, may be used after surgery.

Postoperative teaching includes how to insert, remove, and care for the child’s contact lens. Parents need to be taught the signs and symptoms of infection and increasing intraocular pressure. To provide visual stimulation to the affected eye and prevent further loss of vision, the importance of adhering to any prescribed patching regimen should also be emphasized. Finally, the nurse teaches the importance of returning for follow-up visits to ensure that the lens fits correctly, the vision correction is appropriate, and no signs and symptoms of complications are present. As with glaucoma, the occurrence of some cataracts has a genetic component, so referral for genetic counseling may be indicated.

Eye Surgery

Several eye disorders, as mentioned previously, that are seen in infancy and childhood require surgical correction. Any surgical procedure is stressful for the child and family. Eye surgery is particularly stressful because the child’s visual fields or acuity may be greatly reduced or absent for a period. If both eyes are affected, the child’s ability to maneuver and perform activities of daily living independently is also affected.

The nurse should pay special attention to education. If the child is going home with patches, drops, or any other procedure that must be performed, the family needs to know how to perform this care and should also know the safety precautions involved.