The Child with a Developmental Disability

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Develop understanding of the use of the terms intellectual disability versus mental retardation.

• Identify the various causes of intellectual and developmental disabilities.

• Develop nursing strategies for families caring for a child with Down syndrome.

• Identify the basic diagnostic criteria for the autism spectrum disorders.

• Identify genetic aspects of intellectual and developmental disorders.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Intellectual and Developmental Disorders

Children who have intellectual or developmental disorders experience genetic or external influences that may limit their potential abilities. However, these potential limits will be minimized or maximized by their interaction with the environment. Many intellectual or developmental disorders will respond to early and intensive intervention and close attention. However, children and families face lifelong challenges that require assistance from both health care and educational professionals to maximize the child’s developmental potential. The family of a child with an intellectual or developmental impairment copes with frequent and exceptionally high demands, often including chronic medical and educational challenges that require lifelong management. Independence and self-management should be emphasized throughout childhood and adolescence so that, as the individual reaches adulthood, the possibility of independent living and gainful employment can be maximized.

Developmental Disability and the Americans with Disabilities Act: The Impact of Public Policy

Historically, intellectual, sensory, and developmental disorders were considered to be distinct, although overlapping syndromes. In recent years, the term developmental disability has become an umbrella term to encompass children with intellectual disability, sensory deficits (hearing, vision, and speech), orthopedic problems, and conditions such as cerebral palsy and autism spectrum disorders. Uniting these disorders under the term developmental disability has important legal and policy implications because it unites a number of people who have similar psychosocial and developmental disorders and similar needs for services. From a health policy perspective, united groups are more powerful in gaining legislative and policy recognition. This effort was successful in the passage and enactment of the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000 (PL 106-402) (2000). The purpose of this act is to attempt to ensure equal rights and accessibilities for all disabled individuals.

In this bill, the United States Congress defined a developmental disability as having the following components (Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000):

As a result of this bill, and also of earlier legislative efforts, such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1997, every disabled child must have a written individualized education plan (IEP) that outlines specialized instruction and services the public school system will provide. The child’s parents and school personnel design the plan following an educational assessment. School nurses often participate in IEP evaluations, providing expert advice about classroom adaptations or medical services needed for these children. When working with these children, teachers, families, and communities, the nurse may serve as a resource for identifying advocacy services.

Nursing goals when caring for children with an intellectual or developmental disorder or disability include accurate assessment of the specific cause and nature of the disorder or disability, and the identification of possible co-morbidities and risk factors. Complete information enables the nurse to plan interventions that will maximize the child’s development and adaptive functioning. Nursing care in this specialty area always includes assessment, referral, education and follow-up, and advocacy for the child and family members.

Intellectual and developmental disorders are frequently co-morbid, with both occurring together. These children are also at risk for psychosocial disorders. For example, a child who is diagnosed with Asperger syndrome is at risk for symptoms of depression. In the same manner, children who are diagnosed with autism frequently also show symptoms of intellectual disability.

The nurse is an integral part of the multidisciplinary team that manages the care of a child with a developmental disorder. The nurse is involved in early assessment of the child, support of the family, assistance with self-care training and behavioral training, referral to support services, and providing the necessary nursing care for other disabilities the child may have. School and community nurses need a broad range of knowledge to support children who have multiple intellectual and physical disabilities.

The first section of this chapter reviews intellectual impairment disorders (formerly referred to as disorders associated with mental retardation.) The considerations in the care of a child with Down syndrome will illustrate nursing care for children with intellectual disabilities. The second section of the chapter gives an overview of developmental disorders that have clear genetic causes (fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome). The third section looks at developmental disorders where the cause is related to environmental or prenatal toxins (fetal alcohol syndrome). The last section examines the autism spectrum disorders. The nursing care for a child with autism will demonstrate considerations in planning care that promotes maximal development for all children with developmental disorders and their capability to move through the expected stages of childhood development.

Terminology

Mental Age, Functional Age, Adaptive Functioning

Children with developmental disabilities have impairments in motor skills or sensory ability that may be minor and manageable, or they may demonstrate significant impairment in intellectual, functional, and adaptive development. Mental age and functional age are terms used to compare a child’s current ability with children of the same chronologic age. These terms are generally more useful than references to the intelligence quotient (IQ), which can be misleading, especially for children with language disabilities. Mental age gives the caregiver information regarding level of intellectual understanding. For example, if an individual has a mental age of 5 years, the nurse’s explanations should be simple and specific, regardless of chronologic age. However, if the individual has a mental age of 12 years, the nurse’s explanations can be complex and use some abstractions. Functional age refers to the level of adaptive function, the level of coping that a child has developed that supports activities of daily living (ADLs), communication skills, and social skills (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities [AAIDD], 2011). Maximizing the child’s adaptive function by supporting identified strengths and supplementing weak areas will allow the child to develop realistically to full potential (AAIDD, 2011). It is possible for a child with a low mental age to function well beyond what would be expected. This is an example of a high level of adaptive functioning.

Intellectual Impairment and Intellectual Disability

Intellectual impairment is a descriptive term that denotes a significant limitation in both intellectual and functional capacity. This means that the impairment manifests in measured intelligence (i.e., IQ) and also in adaptive behavior. Intellectual impairment distinguishes intellectual or cognitive deficits from specific, limited sensory deficits (e.g., vision, hearing). It also differentiates emotional or psychological disability. Specific intellectual impairments are considered through assessment of language, cognition, academic ability, self-help skills, social behaviors, and motor performance.

The term is used to describe conditions that originate before the age of 18, with significant evidence of below-average intellectual functioning and adaptive functioning in areas such as communication, ability to work, home living, community use, health and safety, leisure, self-care, social skills, self-direction, functional academics, or work abilities (AAIDD, 2011). The level of intellectual disability may be mild, moderate, severe, or profound. Intellectual impairment can result from genetic mutations that cause malformations of the brain and central nervous system (CNS), or it may result from injury, infection, anoxia, poisoning, prenatal alcohol use, brain trauma, accidents, Down syndrome, or other inherited disorders. In some cases the cause may be unknown.

Children with intellectual disabilities require support and interventions to acquire self-care and adaptive skills; however, many children are educated, hold a job, and independently accomplish some self-care activities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009; National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities, 2011).

Intellectual Impairment versus Mental Retardation

Intellectual impairment has replaced the term mental retardation (MR) to describe people with below-average general intellectual functioning. Over time “mental retardation” has generally been removed as a clinical classification, and the term was formally removed from IDEA in 2010 (National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities, 2011). This is a significant decision, and a number of rationales were cited for the change, including the scientific inaccuracy of the term retardation and the stigma associated with the term (AAIDD, 2011). As a result of this change in clinical classification, the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR) voted to change the name of its organization (and its publications) to the American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD, 2011).

Autism Spectrum Disorders versus Pervasive Developmental Disorders

Pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) vary widely in etiology and level or type of impairment. They are termed spectrum disorders because the range of impairment can be mild or severe.

Some of the PDDs are clear genetic disorders such as Rett syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome. These disorders are characterized by recognizable physical characteristics and usually by impairment in physical development and cognition, as well as by significant intellectual impairment.

The PDD classification also includes the autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), where genetic influence is likely, but less definitive. The ASDs include attention-deficit disorder (ADD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Asperger syndrome, and autism. A third group within the PDD classification represents disorders that result from toxins or prenatal influences, such as fetal alcohol syndrome.

Although these disorders are different in origin, they remain linked in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., Text revision). The expected release of the fifth edition of the DSM in 2013 may clarify some of these classifications (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000).

The PDDs discussed in this chapter include Rett syndrome, fragile X syndrome, fetal alcohol syndrome, failure to thrive, and the ASDs of Asperger syndrome and autism. ADD and ADHD are discussed in Chapter 53.

Etiology of Intellectual Disabilities and Pervasive Developmental Disorders

These disorders may be the result of genetic mutations, prenatal environment, or congenital or early environmental factors such as maternal substance abuse or lack of stimulation in early childhood. They may also be the result of head injury, asphyxia, intracranial hemorrhage, infections, poisoning, or the presence or treatment of a brain tumor. Developmental disorders have more than 350 known causes, but a specific cause is unknown in nearly half of all diagnosed cases. New etiologies are being identified, and underlying mechanisms of known causes are becoming more clearly understood.

As medical technology advances, a medical basis for intellectual and adaptive impairments is found in an increasing proportion of intellectually impaired children. Often the cause is a

subtle but nonetheless significant biologic factor, such as minor chromosomal abnormalities, rare genetic syndromes, subclinical lead intoxication, nutritional deficiencies, or exposure to numerous prenatal risks or trauma. Evidence suggests that early intervention programs that promote neurodevelopment can show benefit for later neurologic integrity and intellectual ability. Low socioeconomic status and related factors have also been consistently reported as influencing intellectual function (Box 54-1).

Incidence of Intellectual and Developmental Disorders

In the United States it is estimated that a PDD is diagnosed in approximately 1 of 150 children. Boys are more likely to be diagnosed with PDD than are girls (Cole, 2008; Rizzolo & Cerciello, 2009). Families with children or adolescents who are mildly or moderately impaired are likely to care for children at home. An increased incidence of intellectual disability is reported in the early school years, and then the incidence declines in late adolescence as the children leave the formal education setting and are assimilated into the adult world. Most intellectually impaired individuals are able to marry (often to individuals with normal intellectual functioning), maintain employment, and have satisfying relationships.

Psychiatric co-morbidity is common in people with both intellectual and developmental disorders, probably because underlying conditions that cause intellectual disabilities also affect areas of the brain that regulate emotional state. The most frequent accompanying diagnoses include disruptive behavioral disorders, depression, and atypical psychosis. Prevalence estimates for co-morbidity between psychosocial disorders and developmental disorders are up to 60% to 70%, but the incidence is lower in children and adolescents compared with adults with developmental disorders (Sadock & Sadock, 2008).

Developmental disorders may increase risk for child abuse. According to the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, 11.1% of all reported child abuse cases involved children with disabilities, including developmental disabilities (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010a). Possible reasons for this strong relationship are the intense stress experienced by families of disabled children, parental isolation, and unrealistic expectations for the child’s performance because of a lack of knowledge about normal growth and development. Despite available funding and support groups, families of children with developmental delays often feel isolated from supportive services and report that professionals have limited understanding of their children’s needs. These factors further perpetuate the sense of helplessness and lack of control in these family systems, leading to a climate with a heightened potential for abusive behaviors.

Manifestations

The cardinal sign for the developmental disorders is delayed achievement of developmental milestones. Specific congenital malformations often result in specific clinical manifestations. Also, the severity of the impairment affects the types and frequency of problem behaviors (Box 54-2).

In addition to general clinical manifestations based on the degree of impairment, many syndromes are characterized by features that are helpful in determining the cause of the disability. Two genetic disorders in which intellectual disability is a central feature are Down syndrome and fragile X syndrome. An infant born with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) will show both intellectual and developmental disorders and also specific physical growth, facial, skeletal, and cardiac features.

Many disorders associated with intellectual disability can further limit a child’s adaptive skills. These include cerebral palsy, visual deficits, seizure disorders, communication deficits, feeding problems, ASDs, failure to thrive, and ADHD. Speech and language development are often profoundly affected. Depending on the condition, seizure disorders frequently develop as the child matures.

Although children who are intellectually impaired can be generally physically healthy, the presence of associated disabilities may place these children at increased risk for illness (Figure 54-1). For example, if a child who is intellectually impaired also has cerebral palsy, the risk for gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration pneumonia is high. Motor or swallowing problems may result in inadequate oral intake or insufficient weight gain.

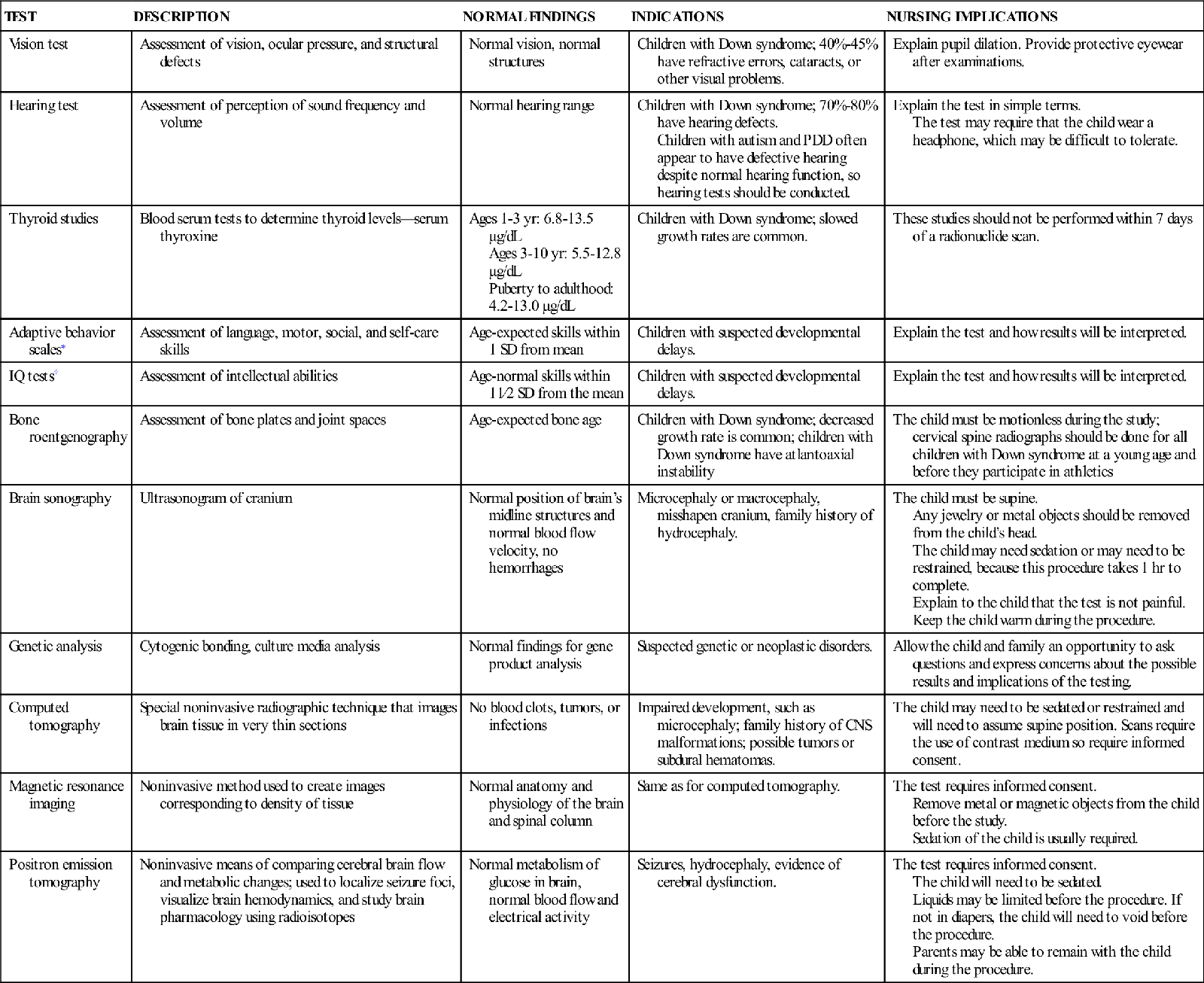

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnostic evaluations may be performed during pregnancy, during the neonatal period (based on risk factors), or after the child fails to achieve expected developmental milestones. Early identification is important so that early intervention treatment plans can be established. Tests may be general or specific for the neurologic or intellectual area in question. Several tests assess the child’s current level of functioning and help the clinician anticipate persistent intellectual disabilities. These tests—which may involve pencil-and-paper tasks, motor tasks, sensory tasks, or some degree of intellectual processing—help determine both the severity and type of intellectual disability (Box 54-3). Learning disabilities are often identified by using some of these same instruments, and many are available through the school system. Nurses also can learn to administer developmental screening tools. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends formal developmental screening and surveillance for all children at ages 9 months, 18 months, and 24 to 30 months (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006/2010) (see Chapter 5 and www.aap.org website). Often, a diagnosis of developmental disorder is not made until the child begins school and has significant academic failure, prompting formal psychological and neurologic testing. Routine assessment of development during pediatric visits, however, is the best method of early detection.

New understandings of human behavior suggest that levels of functioning vary in every individual, and that a one-time test offers information only about that moment in time. Accurate scores are best obtained by repeated testing over a short period of time, giving a range of scores that may more accurately describe a child’s potential.

Management

Both general strategies and strategies designed to keep children safe provide the basis for managing children with intellectual or developmental disorders or disabilities.

General Strategies

Therapeutic management depends largely on community and educational resources. Obtaining services for these children, however, requires multidisciplinary efforts and strong advocacy on the part of both parents and professionals. Reduction in the occurrence of developmental disorders is a national priority identified in Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2010b). Adequate prenatal care is of primary importance. An additional priority related to children with disabilities is increasing the percentage of time children with disabilities spend in regular school programs (USDHHS, 2010b).

For children with associated medical co-morbidities, medical strategies are directed toward preventing and treating infections, correcting structural deformities, and treating associated behaviors, such as aggressiveness. Corrective measures might include congenital heart surgery for malformations, inserting tympanostomy tubes, or placing splints on joints that are hypotonic and hyperextended. The treatment of behavioral difficulties and psychosocial disturbances may involve administration of medications.

Safety Challenges

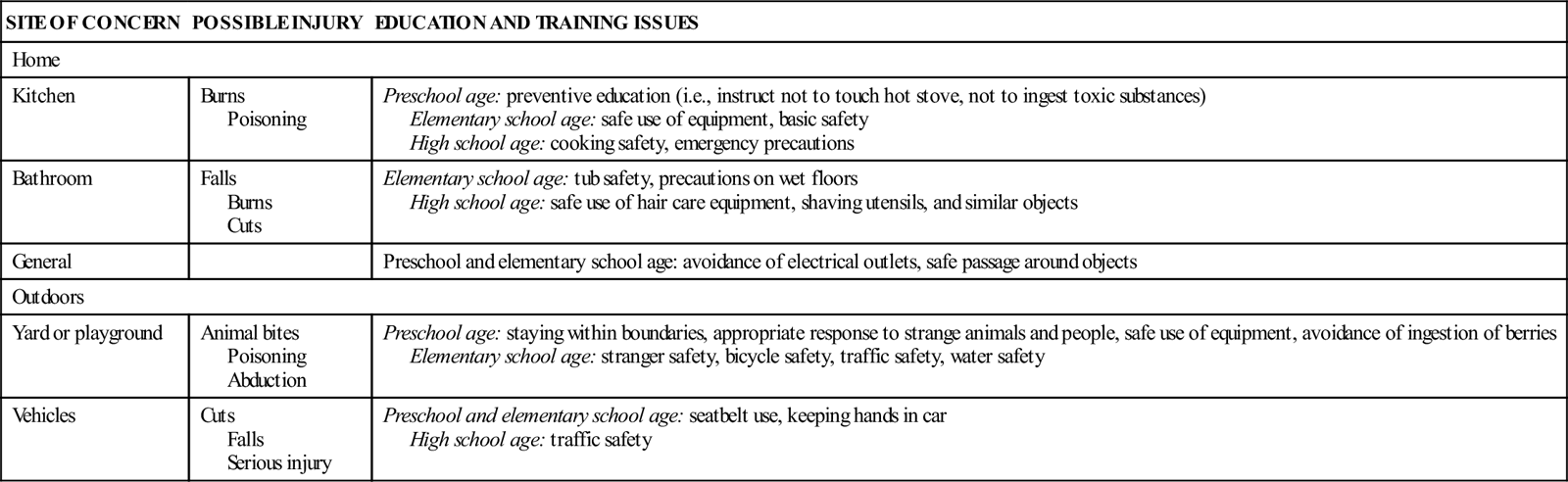

Children who are intellectually impaired are less capable of managing environmental challenges than are their peers who are unimpaired. Because of impaired executive and motor functioning, injuries are generally more common when compared to same-age children. Among preschool-age children, however, injuries are less common in those with intellectual disability, perhaps due to parental oversight and less exposure to risk. Table 54-1 presents some safety issues to be taught in the home and in the community. Although the learning needs of children who are intellectually impaired are similar to those of children without disabilities, children with intellectual disabilities may need prolonged teaching, more demonstration during teaching, frequent verbal and visual reminders, and more practice. Resources for schools and teachers have been essential in helping children with intellectual or developmental disabilities integrate into classrooms (National Educational Psychological Service, 2011).

TABLE 54-1

SAFETY CONCERNS FOR DEVELOPMENTALLY DELAYED OR IMPAIRED CHILDREN

| SITE OF CONCERN | POSSIBLE INJURY | EDUCATION AND TRAINING ISSUES |

| Home | ||

| Kitchen | Burns Poisoning | Preschool age: preventive education (i.e., instruct not to touch hot stove, not to ingest toxic substances) Elementary school age: safe use of equipment, basic safety High school age: cooking safety, emergency precautions |

| Bathroom | Falls Burns Cuts | Elementary school age: tub safety, precautions on wet floors High school age: safe use of hair care equipment, shaving utensils, and similar objects |

| General | Preschool and elementary school age: avoidance of electrical outlets, safe passage around objects | |

| Outdoors | ||

| Yard or playground | Animal bites Poisoning Abduction | Preschool age: staying within boundaries, appropriate response to strange animals and people, safe use of equipment, avoidance of ingestion of berries Elementary school age: stranger safety, bicycle safety, traffic safety, water safety |

| Vehicles | Cuts Falls Serious injury | Preschool and elementary school age: seatbelt use, keeping hands in car High school age: traffic safety |

Disorders Resulting in Intellectual or Developmental Disability

Disorders that result in intellectual disability, developmental disability, or both can be classified and discussed according to any of a number of schemes. To facilitate understanding of their common features and specific differences, disorders are discussed in the following order:

• Disorder of intellectual impairment: Down syndrome

• Disorders of known genetic cause: Fragile X syndrome and Rett syndrome

• Disorders related to environmental alterations: Fetal alcohol syndrome, nonorganic failure to thrive

• Disorders with little understood genetic influence: Autism spectrum disorders