6 The changing health care system and its implications for the PACU

The health care system in the United States is one of the nation’s largest and most important economic sectors. It consists of all the resources and activities whose primary purpose is to promote, restore, or maintain the health of the American people.1 Continuous efforts have been made to improve the health care system’s ability to produce care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.2 An emphasis on safety implies that medical care should bring minimal harm to patients. Effectiveness highlights the importance of providing evidence-based services only to those who could benefit. Patient-centeredness emphasizes individualized care and the patients’ pivotal role in all clinical decisions. Timeliness underscores the significance of “reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care.”2 Efficiency focuses on eliminating waste in the production of medical care, including overuse of medical resources and undue administrative costs. Finally, equity stresses the need for “providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.”2 As health technology and the role of government in financing care have increased in the past 10 years, the health care system has played an increasingly important role in people’s lives. The rapid development of medical science and technology, changing economic and political environment, and soaring consumer expectations have profoundly changed what health care is and how it can be delivered. It is critical for postanesthesia nurses to understand the nation’s health care system.

A health care system is shaped by four functional components: financing, workforce development, service delivery, and regulation.1 This chapter provides a broad overview of these components, including how the health care system is financed, who provides health care services, what medical services are produced, and role of the government in the health care system. There is also a discussion of the issue of the uninsured population, a summary of the recent health care reform legislation, and an explanation of the implications for the post anesthesia care unit (PACU) and perianesthesia nurses.

Health care financing

In the United States, the private sector has a larger role in paying for health care costs than in most developed countries. Public programs are focused on health care for special population subgroups, such as senior citizens, low-income populations, veterans, and active duty and retired military personnel and their dependents. The financial burden of health care is shouldered by three major sponsors in the United States: businesses, households, and governments.3 Health care costs are billed through private insurance plans, out-of-pocket payments, philanthropic funds, and public programs.

Private business

Private businesses contribute to approximately one fifth of health care spending, in the form of employer-sponsored health insurance, contribution to Medicare, workers compensation, disability insurance, and worksite health care.3 Employers are the leading source of health coverage. The majority of employers (69% in 2010) offer health insurance as a fringe benefit to cover their employees as well as their employees’ dependents.4 Federal, state, and local governments, as employers, also make contributions to private health insurance programs to insure public employees. For example, in 2009, the federal government contributed $26.8 billion to the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program to cover more than 8 million federal employees, retirees, and their dependents, including members of the U.S. Congress.5

Employer-sponsored health insurance has been designed predominantly through managed care plans of various kinds in recent decades. Managed care plans are lower cost alternatives to conventional indemnity insurance by incorporating a wide range of organizational and financial arrangements to organize, reimburse, and monitor services. The most common type of managed care plans is the preferred provider organization (PPO). A PPO selectively contracts with hospitals and other providers to form a network and creates financial incentives for members to use network providers. The incentives can include lower deductibles, lower copayment, and coinsurance. The advantage to the PPO is that network providers negotiate lower reimbursement rates in exchange for higher anticipated volume. Another type of managed care plan, the health maintenance organization (HMO), is more restrictive. Members are required to use in-network providers and must be authorized by their primary care physician to see a specialist. HMO plans usually have lower out-of-pocket payments than PPO plans. Point-of-service (POS) plans are hybrids of PPO and HMO plans in which enrollees can choose to pay extra at the point of a particular service to see a non-network provider. Some employers also offer a high-deductible health plan with savings option (HDHP/SO). The annual deductible of a typical HDHP plan can be $2000 or higher for single coverage. Health reimbursement arrangements and health savings accounts are linked with such plans, allowing employees to save for medical expenses on a tax-free basis. In 2010, 58% of covered employees were enrolled in PPOs, followed by HMOs (19%), HDHP/SOs (13%), and POS plans (8%). Approximately 1% were covered by conventional indemnity plans.4

Employers and employees both contribute to the cost of employment-based health insurance. Covered employees on average shouldered 19% of the total premium for single coverage and 30% for family coverage in 2009%,4 approximately $75 monthly for single coverage and $333 monthly for family coverage. Private and public sector employers often vary as to the relative role of health benefits in the total compensation package. From 2000 to 2009, the share of premiums paid by private sector employers dropped from 74.7% to 69.7%. During the same time period, the share paid by the federal government remained at 72% to 73%, whereas state and local governments’ contributions increased from 79.2% to 83%.3

Not all employers provide health benefits to their employees. Those offering insurance benefits tend to be large firms with well-paid workers.4 Even if employers offer insurance, employees can choose not to participate if the premium share is too high, the value of the benefits too low, or if the employee has higher value options for coverage elsewhere (e.g., through a spouse). Employer-based insurance coverage is clearly tied to employment. In the economic downturn near the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, millions of workers lost their jobs and their insurance coverage. Nearly three of five adults who lost a job with health benefits in 2010 became uninsured.6 Private business health spending decreased 0.5% in 2009, the first decline since 1987, resulting from a 3.2% decrease in employer-sponsored health insurance coverage.3

Households

The financial burden of health care on households consists of three parts: health insurance premiums, out-of-pocket payments (deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance), payments for services that are not covered by insurance, and the mandatory Medicare payroll tax for employed individuals. Households contributed to 28% of national health spending in 2009, or 6.2% of personal income.3 This average, however, conceals the larger burden on low-income families. In 2010, half of adults from families with incomes less than 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $22,050 for a family of four) spent 10% or more of their income on health care.6

Direct household spending on health care can be strongly influenced by economic conditions. The growth rate of out-of-pocket payments dropped from 3.1% in 2008 to 0.4% in 2009 as consumers postponed medical services during the economic recession.3

Governments

Federal and state governments are charged with funding public health-related programs, including Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is the federal agency that administers these three programs (Medicaid and CHIP are administered jointly with the states.) The federal government also subsidizes employment-based health insurance through tax laws that allow recipients of employer-based insurance to receive these benefits tax free. This subsidy is estimated to be $177 billion in the year 2011.7

Medicare is the nation’s largest health insurer. It covers people age 65 or older, those with certain disabilities, and those with end-stage renal disease. The program is organized into four parts. Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance) pays for inpatient care in hospitals, skilled nursing services, hospice, and home health care. The Part A program is financed primarily through the Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax, which funds Social Security and Medicare. Currently, the Medicare payroll tax is 2.9%, with the worker and the employer each paying 1.45%. Self-employed individuals must pay the entire 2.9% tax.

Medicare Part B (Medical Insurance) covers doctors’ services and tests, outpatient care, some home health services, durable medical equipment, and certain preventive services. Part B is financed through premiums paid by enrollees and contributions from general revenues of the U.S. Treasury. Beneficiary premiums are currently set to cover approximately 25% of the per capita cost of Part B. In 2011, the Part B premium is $96.40 for those enrolled before 2010, $110.50 for those enrolled in 2010, and $115.40 for all others. Individuals with yearly incomes higher than $85,000, or couples with income above $170,000, pay premiums that range from $161.50 to $369.10 per month.8

Medicare Part D (Medicare Prescription Drug Coverage) helps to pay for prescription drugs. People eligible for Medicare participate on a voluntary basis and pay a monthly premium. All prescription drug plans are administered by Medicare-approved private insurance companies. The premium, cost sharing, and drugs covered vary from plan to plan. As of January 2008, more than 25 million Medicare beneficiaries (57%) were enrolled in Part D plans.9

Medicaid is a joint federal and state program that provides comprehensive medical and long-term care coverage for individuals with limited income and resources and for those with major disabilities. Although the federal government provides broad guidelines, states have a wide degree of flexibility to design the eligibility criteria and benefit package. For example, California’s Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) covered 29% of its total population in 2007, while the Medicaid program in Nevada covered 10% of its population in the same year.10 Income limits for program eligibility for single adults varied from 17% of the FPL in Arkansas to 215% of the FPL in Minnesota.11 In general, eligibility rules for children are more generous than for adults in all states. Medicaid plays a key role in ensuring access to care for the low-income population.

CHIP represents another joint effort on the part of federal and state governments. This program provides free or low-cost health insurance coverage to children up to 19 years old in families with incomes exceeding eligibility limits for Medicaid who cannot afford private health insurance. Uninsured children in families with incomes up to $44,100 a year (200% of the FPL for a family of four) are eligible for the CHIP in many states. The program generally covers doctor visits, hospitalizations, prescription drugs, and vision and dental care. Pregnant women and other adults may also be covered by the program. Similar to Medicaid, CHIP is administered by each state under broad federal requirements; therefore eligibility, benefits, premiums, and cost sharing are different from state to state. For the federal fiscal year 2010, a total of 7.7 million children were enrolled in CHIP at some point during the year.12

Health care spending by governments amounted to 44% of national health expenditures in 2009, with the federal government accounting for approximately 27% and state and local governments accounting for 16%.3 Government health care spending is projected to account for more than half of total health care spending by 2012.13

The U.S. health care system is the most expensive one in the world. National health spending was $2.5 trillion in total, or $8086 per capita in 2009.14 The ratio of health spending to the gross domestic product (GDP) reached 17.6%.14 Health care spending in the United States is significantly higher than in other industrialized countries. For example, France, Switzerland, and Germany devoted 11.2%, 10.7%, and 10.5%, respectively, of their GDP to health care in 2008.15 The United States spent more than twice as much as relatively rich European countries on health care per capita. Adjusted for purchasing power parity, France spent $3696 per capita on health care in 2008, Germany spent $3737 per capita, and the United Kingdom spent $3129 per capita.15 National health care expenditures are projected to grow at an average annual rate of 6.1% (1.7 percentage points faster than GDP), climbing to $4.5 trillion, or 19.3% of GDP by 2019.13

The uninsured population

The United States is one of three countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that do not offer health coverage to all of its citizens (Mexico and Turkey are the other two.) Although the elaborate patchwork of public and private coverage options works well for many of those who have employer-sponsored health benefits or who are eligible for public programs, it has many holes. In 2009, for example, 676,000 elderly people did not qualify for Medicare.16 Two of every 10 individuals younger than 65 years are not covered by employment-based health insurance, are not eligible for Medicaid or other public programs, and are left uninsured.16 The resulting uninsured population was 50 million in 2009.16

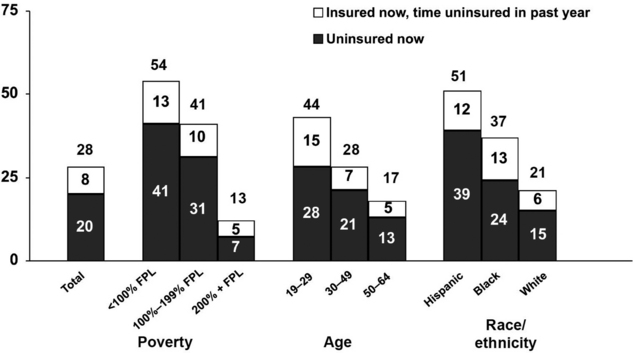

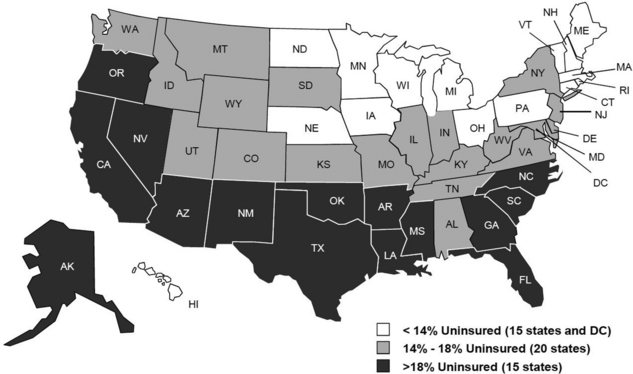

Adults with low and moderate incomes, young adults, and racial or ethnic minority groups, such as Hispanics and blacks, are more likely to be uninsured.6 Those between 19 and 29 years of age have the highest uninsured rate (28%) of any age group (Fig. 6-1). Noncitizens (legal and undocumented) are approximately threefold more likely to be uninsured than citizens.16 Insurance rates vary across states because of differences in average income, employment opportunity, and Medicaid policy at the state level (Fig. 6-2). Massachusetts has an uninsured rate of less than 5%, whereas the rate exceeds 25% in New Mexico, Florida, and Texas.16

(From Collins SR, et al: Help on the horizon: how the recession has left millions of workers without health insurance, and how health reform will bring relief, The Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, New York, 2011, The Commonwealth Fund.)

FIG. 6-2 Uninsured rates among nonelderly by state, 2009 to 2010.

(From Kaiser Family Foundation: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured/Urban Institute analysis of 2010 and 2011 ASEC Supplement to the CPS, two-year pooled data, available at http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?ch=2345. Accessed September 20, 2011.)

Having no health insurance negatively affects the financial condition, health-seeking behavior, and health outcomes of the uninsured. Three of five uninsured adults reported having problems paying medical bills or having accrued medical debt, nearly twice the rate of the insured population.6 Because they have to pay for medical bills out of pocket, the uninsured are inclined to delay or forego needed health care. Two thirds of the adults who were uninsured in 2010 reported experiencing one or more of the following: failing to fill a prescription; skipping a medical test, treatment, or follow-up visit; choosing not to see a doctor when sick; or not seeing a specialist because of cost.6 Emergency department services are often the only option for the uninsured when medical care is unavoidable. The uninsured are more likely to be in poor health than the insured. Uninsured adults were more than twice as likely to report being in fair or poor health as those with private insurance.16

Health care workforce

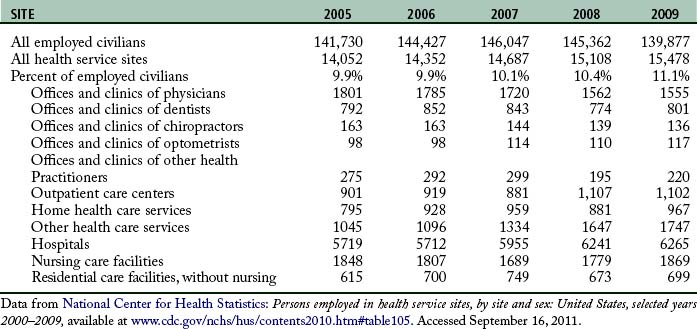

A capable and motivated health care workforce is essential to achieve national health goals. The health care industry is the largest employer in the nation. More than 15 million people worked in this enterprise in 2009 (Table 6-1). Major categories of health care professionals include physicians, dentists, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses (LPNs), pharmacists, health services administrators, and allied health professionals. In addition, millions more work in health-related industries to produce supplies, capital goods, and services for people providing direct patient care.

Physicians are central to the delivery of health care services. They are responsible for the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of patients. Even as insurance companies and health care organizations create incentives to influence the preferences of patients and the practice pattern of physicians, physicians still exert enormous power in controlling and directing the use of medical inputs in the production of health care services. Those wishing to practice allopathic medicine must get a four year undergraduate degree and a doctor of medicine (MD) degree from an accredited medical school, pass a series of the United States Medical Licensing Examination tests offered by the National Board of Medical Examiners, and complete a supervised residency program. Physicians must be licensed by every state in which they practice. Those who wish to further specialize in areas such as cardiology or pediatric surgery must complete a fellowship beyond the residency and typically sit for specialty board examinations to achieve voluntary board certification. Similar requirements exist for practitioners of osteopathic medicine (i.e., doctor of osteopathic medicine).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree