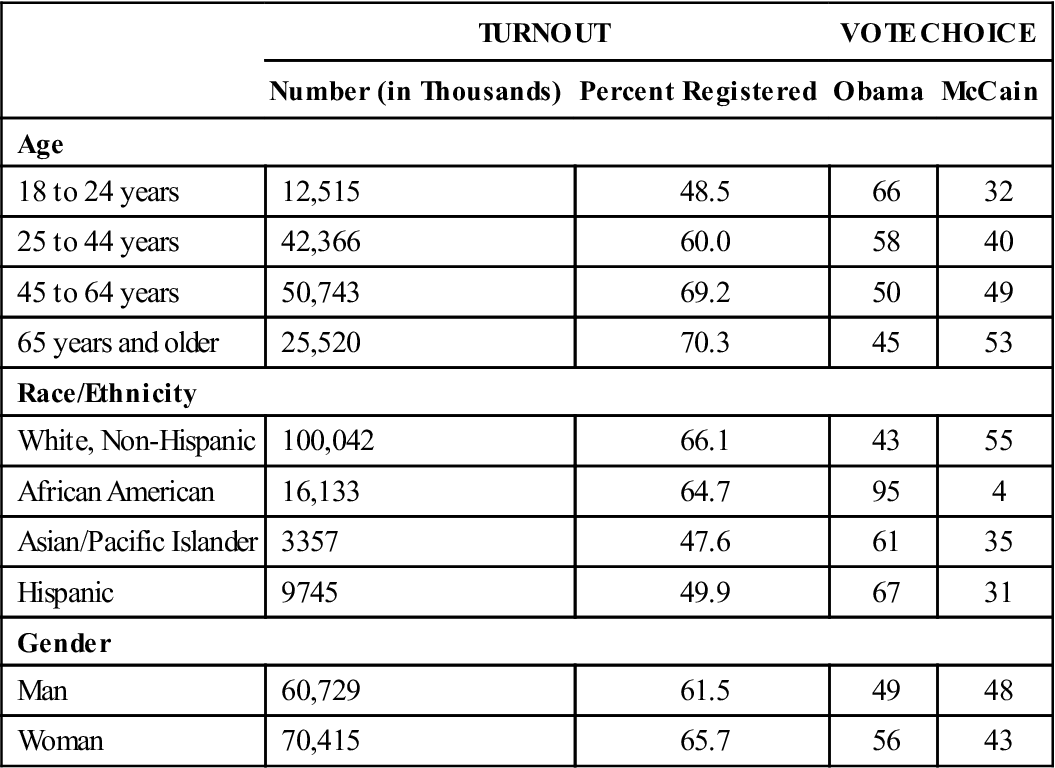

Karen O’Connor and Jon L. Weakley “Suffrage is the pivotal right.” —Susan B. Anthony American democracy requires elected officials in the legislative and executive branch to create public policy. Legislation is created in legislatures and Congress and signed into law by the president or governor. Consequently, it is critical who those legislators and chief executives are because they determine whose interests are represented in the policy arena. Citizens exercise a key political act when they vote for candidates who support particular policy positions. In the United States, opportunities to vote abound. Elections range from local party officials to those for the U.S. President and members of Congress. Thus, the 3.1 million nurses in the U.S. have significant potential to affect health policy through the ballot as well as having clear policy preferences to articulate to legislators. As the 2009-2010 debates about health care revealed, it is crucial to have elected officials who support the interests of the health care community. Yet U.S. voter turnout for elections remains low compared to other industrialized nations, perhaps due to the sheer number of elections and lack of clarity of issues in this country. Examining and understanding basic election law, voting behavior, how campaigns work, and how to lobby optimizes the potential for nurses and voters more generally to affect the policy process. The Framers of the U.S. Constitution initially granted voting rights to all property-owning, white men. But, as our notion of equality expanded, so did voting opportunities for additional groups. States are granted the right to establish voter standards unless outlawed by amendment or by U.S. Supreme Court decisions. Over time, the Constitution was amended to grant suffrage first to free men regardless of “race, color … [or] previous condition of servitude,” (Fifteenth Amendment, 1870), then women (Nineteenth Amendment, 1920), and, most recently, those age 18 and older (Twenty-Sixth Amendment, 1971). Currently, there are attempts in many states to re-enfranchise the more than 5 million convicted felons who are barred from voting. The U.S. Constitution prohibits poll taxes (Twenty-Fourth Amendment, 1964), which were passed largely by Southern lawmakers with the intent to disenfranchise largely poor African Americans. Federal legislation has also eliminated literacy tests and property ownership as qualifications to vote. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was enacted with support from President Lyndon B. Johnson. The Act targeted all of the southern states and others with high concentrations of minority voters—particularly African Americans—whose voter turnout lagged behind their percentage of the voting-age population. Recognizing that voter repression and intimidation was happening, the Act streamlined many state election procedures by introducing national standards (and compliance measures) designed to promote electoral equality. Where necessary, it also authorized the U.S. Attorney General to replace local voting registrars with federal registrars, and procedures to register voters were standardized in specific states. The immediate consequence was to enfranchise large blocks of African-American voters, particularly in the South. It also caused formerly conservative Democrats to join the Republican Party. Voter registration of minorities and the poor continued to lag behind that of white voters until the early 1990s. Grassroots civil rights and good government organizations around the country pushed for voter registration reform, citing much higher registration and turnout rates in other nations. In many locales, registration was difficult. Prior to passage of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (known hereafter as the “Motor Voter law”), modes of registration varied widely from state to state, from the ease at shopping malls and post offices to more difficult access in isolated board of elections offices, removed from public transportation. Behind the push for the Motor Voter law was the argument that increased accessibility of voting registration would increase voter turnout. When President Bill Clinton signed the Motor Voter law, voter registration sites were expanded specifically to include social services and motor vehicle registry offices, hence the appellation. While the Motor Voter law was effective in increasing registration dramatically, its effects on actual turnout were less notable (Brown & Wedecking, 2006). In 2000, the hotly disputed presidential election between Vice President Al Gore and Texas Governor George W. Bush produced a massive albeit brief public outcry for reforms of voting methods. Across the nation, especially in Florida, voting technology was revealed to be outdated, malfunctioning, or still inaccessible for certain voters, especially African Americans and Hispanic people who repeatedly found their names wrongfully purged from lists of eligible voters. With visions of hanging chads dancing in their heads, members of Congress passed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) in 2002. It provided federal funding to states and localities to replace old voting technologies. It also mandated that at least one voting device at each precinct be accessible to voters with disabilities. The act also allows voters whose names do not appear on registration lists to vote with provisional ballots, which can later be verified, and if proven legal, counted. This measure allows all citizens who are properly registered to have their votes counted. Although these reforms sought to expand not only the number of Americans registered to vote but also the percentage of those voting, overall turnout increased only moderately after HAVA’s passage. Still, many new technologies sought to streamline the voting process as well as improve its ease and accuracy. The efforts were not without controversy. For example, many voters argued that some digitized ballots that leave no paper trail for verification could be manipulated easily or sabotaged. Steps have been taken to ameliorate these concerns, but the reforms have been gradual and have not yet yielded immediate, tamper-free, accurate results across localities and states (Renner, 2008). Congress has considered a variety of bills to modify current HAVA verification standards, such as requiring all states to have voter-verifiable paper audit trails, but these efforts have failed and have lost their sense of immediacy as the tainted 2000 election faded from memory and was replaced by concerns about the economy, health care, and two wars. Unless a requirement is specified in the Constitution or by federal law, states have the power to define and change election laws. Despite the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Motor Voter law, and HAVA, voting laws still vary considerably from state to state. All states allow some sort of early or absentee voting with mail-in ballots if individuals are unable to vote in their designated precincts on Election Day. Modes of voting are different from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Oregon residents, for example, vote by mail-in ballot only, making voting booths obsolete. As of 2009, nine states allow same-day voter registration, and several states do not require any voter registration at all. In the 2004 and 2008 general elections, many states opened polling places days or even weeks prior to Election Day in a process called early voting; in these states, a significant number of voters opted to vote early. In 2008, early voters who identified as Democrats outnumbered those who identified as Republicans, reversing the earlier trend of Republican dominance in early voting states (Wolf, 2008). HAVA provided a greater range of options and times to register and to vote. Hence, voting is among the simplest ways for nurses to influence public policy since longs shifts on Election Day no longer means that the only opportunity to vote is missed. Research on voting behavior seeks primarily to explain two phenomena: voter turnout (that is, what factors contribute to an individual’s decision to vote or not to vote) and voter choice (once the decision to vote has been made, what leads voters to choose one candidate over another). Turnout is the proportion of the voting-age public that votes. Those eligible to vote include all citizens of the U.S. who are age 18 or older. States regulate voting eligibility in a number of ways, from preventing felons from voting to having strict single-day, limited voting hours. Turnout is especially important in American elections because most candidates are elected in winner-take-all systems, where an election’s outcome can be influenced by a single voter. (A few states still require candidates to receive 50 + 1% of the vote; without it, runoff elections are necessary.) In spite of the reforms, the U.S. continues to lag well behind many other constitutional democracies in terms of voter turnout. Many industrialized societies report that upwards of 90% of all eligible voters do so. In contrast, only about 63% of eligible voters went to the polls in the 2008 presidential election. Even though pundits and academics alike were expecting historic turnout in light of then-Senator Barack Obama’s (D-IL) voter mobilization efforts and apparent energizing of young voters, only modest gains in overall voter turnout were recorded (Gans, 2008). Turnout is of great concern, especially if non-voting is seen as a sign of political alienation, dissatisfaction with the status quo, anger at negative campaigns, and/or voter cynicism. Why such low voter turnout rates? According to one 2008 Census Bureau study, 18% of Americans say that school or work conflicts made them too busy to vote. Approximately 15% cite illness or personal emergencies in explaining why they did not vote. Other explanations include apathy, being out of town, not knowing or not liking the candidates, registration problems, or shear forgetfulness. A breakdown of turnout rates by demographic categories reveals dramatically different turnout rates among different groups (Table 73-1). According to the table, turnout was lowest among the Asian/Pacific Islander population and highest among White, Non-Hispanic people. Turnout rates increase with age, and a higher percentage of women than men voted in the 2008 presidential election. TABLE 73-1 Voter Turnout and Vote Choice by Age, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender, 2008 Presidential Election Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Retrieved from www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/voting/013885.html.

The American Voter and the Electoral Process

Voting Law: Getting the Voters to the Polls

A Call for Reform

Voting Behavior

Voter Turnout

TURNOUT

VOTE CHOICE

Number (in Thousands)

Percent Registered

Obama

McCain

Age

18 to 24 years

12,515

48.5

66

32

25 to 44 years

42,366

60.0

58

40

45 to 64 years

50,743

69.2

50

49

65 years and older

25,520

70.3

45

53

Race/Ethnicity

White, Non-Hispanic

100,042

66.1

43

55

African American

16,133

64.7

95

4

Asian/Pacific Islander

3357

47.6

61

35

Hispanic

9745

49.9

67

31

Gender

Man

60,729

61.5

49

48

Woman

70,415

65.7

56

43

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access