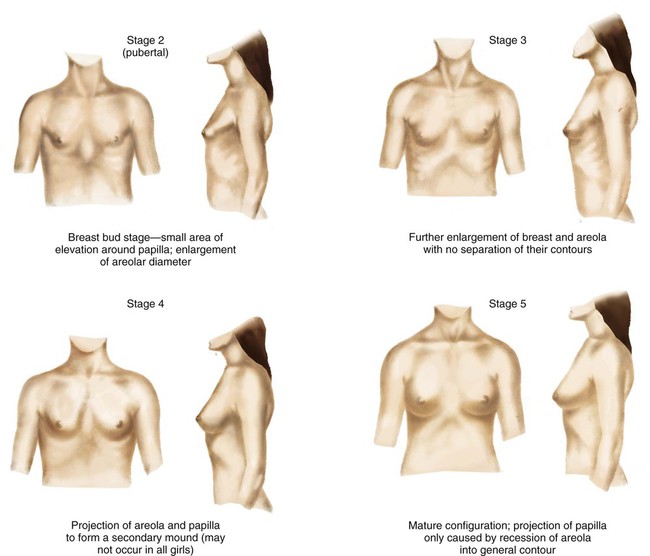

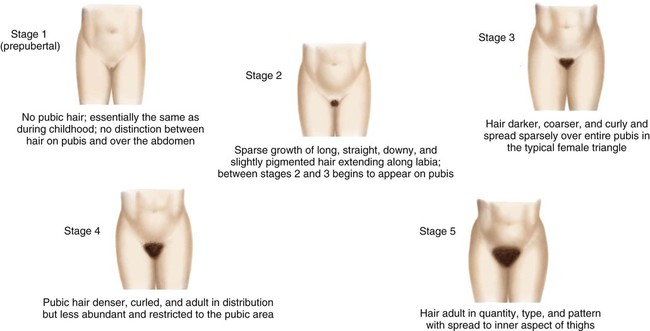

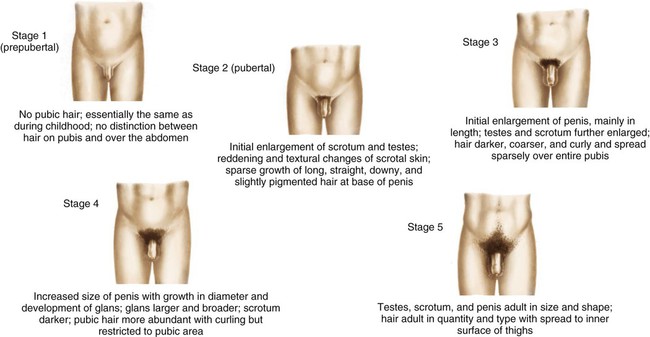

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the physical changes that occur at puberty. • Discuss the reactions of the adolescent to physical changes that take place at puberty. • Demonstrate an understanding of the processes by which the adolescent develops a sense of identity. • Discuss the significance of the changing interpersonal relationships and the role of the peer group during adolescence. • Outline a health teaching plan for adolescents. • Identify the causes and discuss the preventive aspects of injuries during adolescence. • Demonstrate an understanding of common disorders of the male and female reproductive systems. • Demonstrate an understanding of health problems related to adolescent sexuality. • Outline a care plan for the child or adolescent with an eating disorder. • Discuss the manifestations and nursing management of selected emotional and/or behavioral problems. The visible evidence of sexual maturation is achieved in an orderly sequence, and the state of maturity can be estimated on the basis of the appearance of these external manifestations. The age at which these changes are observed and the time required to progress from one stage to another may vary among children. The time from the appearance of breast buds to full maturity may be 1½ to 6 years for adolescent girls. It may take 2 to 5 years for male genitalia to reach adult size. The stages of development of secondary sex characteristics and genital development have been defined as a guide for estimating sexual maturity and are referred to as the Tanner stages (Box 35-1). The usual sequence of appearance of maturational changes is presented in Box 35-2. In most girls, the initial indication of puberty is the appearance of breast buds, an event known as thelarche, which occurs between 8 and 13 years of age (Fig. 35-1). This is followed in approximately 2 to 6 months by growth of pubic hair on the mons pubis, known as adrenarche (Fig. 35-2). In a minority of normally developing girls, however, pubic hair may precede breast development. The average age of thelarche for Caucasian girls is 10 years, with a range of 8 to 12¾ years; for African-American girls, the average age of thelarche is earlier, around 9 years, with a range of 7 to 11 years (Herman-Giddens, 2006). The average age of thelarche for Hispanic girls falls somewhere between the other two groups. The initial appearance of menstruation, or menarche, occurs about 2 years after the appearance of the first pubescent changes, approximately 9 months after attainment of peak height velocity, and 3 months after attainment of peak weight velocity. There is evidence that girls are developing secondary sex characteristics at a younger age with differences noted between Caucasian and African-American girls. The explanation for this is not yet clear but appears to be influenced by being overweight as well as environmental influences. The normal age range of menarche is usually 10½ to 15 years, with the average age being 12 years, 4 months for North American girls (Wu, Mendola, and Buck, 2002). Ovulation and regular menstrual periods usually occur 6 to 14 months after menarche. Girls may be considered to have pubertal delay if breast development has not occurred by age 13 years or if menarche has not occurred within 4 years of the onset of breast development. The first pubescent changes in boys are testicular enlargement accompanied by thinning, reddening, and increased looseness of the scrotum (Fig. 35-3). These events usually occur between 9½ and 14 years of age. Early puberty is also characterized by the initial appearance of pubic hair. Penile enlargement begins, and testicular enlargement and pubic hair growth continue throughout midpuberty. During this period, there is also increasing muscularity, early voice changes, and development of early facial hair. Temporary breast enlargement and tenderness, gynecomastia, are common during midpuberty, occurring in up to one third of boys. The spurts in height and weight occur concurrently toward the end of midpuberty. For most boys, breast enlargement disappears within 2 years. By late puberty, there is a definite increase in the length and width of the penis, testicular enlargement continues, and first ejaculation occurs. Axillary hair develops, and facial hair extends to cover the anterior neck. Final voice changes occur secondary to the growth of the larynx. Concerns about pubertal delay should be considered for boys who exhibit no enlargement of the testes or scrotal changes by 13½ to 14 years of age or if genital growth is not complete 4 years after the testicles begin to enlarge. Nonlean body mass, primarily fat, is also increased but follows a less orderly pattern. There may be a transient increase in subcutaneous fat just before the skeletal growth spurt, especially in boys. This is followed 1 to 2 years later by a modest to marked decrease, which is again more notable in boys. Later, variable amounts of fat are deposited to fill out and contour the mature physique in patterns characteristic of the adolescent’s gender, particularly in the regions over the thighs, hips, and buttocks and around the breast tissue. It should be noted, however, that pediatric obesity has increased in the United States, and it is believed that obesity can change the timing of puberty. Girls with thelarche as the first sign of puberty have earlier menarche and greater body fat and body mass index (BMI) at menarche than girls with adrenarche as the first pubertal sign. Kaplowitz (2008) points out that there is evidence of a causal relationship between obesity and onset of early puberty in girls rather than earlier puberty causing an increase in body fat; no correlations between body fat and earlier puberty in boys have been reported. Hormonal influences during puberty cause acceleration in growth and maturation of the skin and its structural appendages. Sebaceous glands become extremely active at this time, especially those on the genitalia and in the “flush areas” of the body (i.e., face, neck, shoulders, upper back, and chest). This increased activity and the structural nature of the glands are extremely important in the pathogenesis of a common problem of puberty: acne (see Chapter 47). The eccrine sweat glands, present almost everywhere on the human skin, become fully functional and respond to emotional and thermal stimulation. Heavy sweating appears to be more pronounced in boys than in girls. The apocrine sweat glands, nonfunctional in childhood, reach secretory capacity during puberty. Unlike the eccrine sweat glands, the apocrine glands are limited in distribution and grow in conjunction with hair follicles in the axillae, around the areola of the breast, around the umbilicus, on the external auditory canal, and in the genital and anal regions. Apocrine glands secrete a thick substance as a result of emotional stimulation that, when acted on by surface bacteria, becomes highly odoriferous. A number of physiologic functions are altered in response to some of the pubertal changes. The size and strength of the heart, blood volume, and systolic blood pressure increase, whereas the pulse rate and basal heat production decrease (see Appendix C). Blood volume, which has increased steadily during childhood, reaches a higher value in boys than in girls, a fact that may be related to the increased muscle mass in pubertal boys. Adult values are reached for all formed elements of the blood. Respiratory rate and basal metabolic rate, decreasing steadily throughout childhood, reach the adult rate in adolescence. Respiratory volume and vital capacity are increased and to a far greater extent in males than in females. During this period, physiologic responses to exercise change drastically: performance improves, especially in boys, and the body is able to make the physiologic adjustments needed for normal functioning after exercise is completed. These capabilities are a result of the increased size and strength of muscles and the increased level of cardiac, respiratory, and metabolic functioning. Traditional psychosocial theory holds that the developmental crisis of adolescence leads to the formation of a sense of identity (Erikson, 1963). Throughout childhood, individuals have been going through the process of identification as they concentrate on various parts of the body at specific times. During infancy, children identify themselves as being separate from the mother; during early childhood, they establish a gender-role identification with the appropriate-sex parent; and in later childhood, they establish who they are in relation to others. In adolescence, they come to see themselves as distinct individuals, somehow unique and separate from every other individual. The process of evolving a personal identity is time-consuming and fraught with periods of confusion, depression, and discouragement. Determining an identity and a place in the world is a critical and perilous feature of adolescence (see Critical Thinking Case Study). However, as the pieces gradually shift and settle into place, a positive identity eventually emerges. Role diffusion results when the individual is unable to formulate a satisfactory identity from the multiplicity of aspirations, roles, and identifications. Generally, the stated importance of participation in organized religion declines somewhat during the adolescent years. More high school students than post–secondary school young people attend religious services regularly, and, not surprisingly, the younger the adolescents, the more likely they are to view religion as being important to them. Among older adolescents, the importance of organized religion declines more among college students than among those not in college. Late adolescence appears to be a time when individuals reexamine and reevaluate many of the beliefs and values of their childhood. Consistent with developmental changes in value autonomy, the religious beliefs of young people are likely to become more personalized and less bound to the traditional religious practices they may have been exposed to when they were younger. As adolescents mature and form an identity, they may either reject their family’s traditional beliefs or they may decide to conform to those beliefs (Neuman, 2011). Neuman (2011) suggests that adolescents, who are searching for an identity and personal growth, may perceive God as one who accepts them and confirms their self-identity. Religious beliefs in adolescence are also strongly influenced by interpersonal relationships with peers as well as adults in their environment. Greater levels of religiosity and spirituality are associated with fewer high risk behaviors and more health-promoting behaviors, especially for youth living in environments lacking positive influences (Regnerus and Glen, 2003). Nurses play an important role for teens by providing an opportunity to discuss issues regarding spirituality. With advancing adolescence, teenagers become more competent and with this competence comes a need for more autonomy. Although they may be psychologically prepared for independence, they are often thwarted in their efforts by lack of money or other parental barriers. Conflict arises in relation to the teenagers’ outside activities and the elements of privacy and trust. Parental monitoring remains important throughout adolescence and may have a direct influence on adolescent sexual and substance-use behavior. Parents should be guided toward an authoritative style of parenting in which authority is used to guide the adolescent while allowing developmentally appropriate levels of freedom and providing clear, consistent messages regarding expectations. Consistency in guidance and establishing ground rules is extremely important for adolescents even though they may fiercely reject the parents’ wishes. Authoritative style of parenting has been shown to have both immediate and long-term protective effects toward adolescent risk reduction (DeVore and Ginsburg, 2005). However, to gain the trust of adolescents, parents must respect their adolescent’s privacy and show an honest and sincere interest in what the adolescent believes and feels (see Family-Centered Care box). The school is psychologically important to adolescents as a focus of social life. Teenagers usually distribute themselves into a relatively predictable social hierarchy. They know to which groups they and others belong. A sense of school connectedness has been found to predict decreased risk-taking behaviors in adolescents (Bond, Butler, Thomas, et al., 2007). School connectedness is correlated with caring teachers and the absence of prejudice or discrimination from peers. A sense of school connectedness is less dependent on class size, attendance, academic preparation, and parental involvement (Maes and Lievens, 2003). Within the larger groups are smaller, distinct, and rather exclusive crowds or cliques of selected close friends who are emotionally attached to each other. The selection is based on common tastes, interests, and background. Although cliques may become formalized, most remain informal and small. However, each has an identifying feature that proclaims its difference from others and its solidarity within itself, in much the same manner as the adolescent generation as a whole sets itself apart from the adult generation. Cliques are usually made up of one gender, and girls tend to be more cliquish than boys and to have a greater need for close friendships (Fig. 35-4). Within the intimacy of the group, adolescents gain support in learning about themselves, consideration for the feelings of others, and increased ego development and self-reliance.

The Adolescent and Family

Promoting Optimal Growth and Development

Biologic Development

Sexual Maturation

Sexual Maturation in Girls.

Sexual Maturation in Boys.

Physical Growth

Sex Differences in General Growth Patterns.

Physiologic Changes

Psychosocial Development

Developing a Sense of Identity (Erikson)

Individual Identity.

Spiritual Development

Social Development

Relationships with Parents

Relationships with Peers

Peer Group.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree