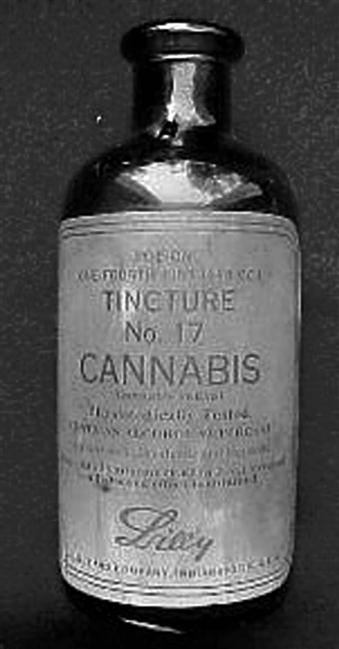

Mary Lynn Mathre “If you want to make enemies, try to change something.” —Woodrow Wilson It’s a drug with an image problem—a drug that has been shown to help certain patients but whose use is forbidden by federal law. We know it as dope, pot, reefer, grass, weed, or ganja. In its clinical form, cannabis, it is a valuable therapeutic aid. However, the Drug Enforcement Administration (the federal agency responsible for placing drugs in categories on the controlled substances schedule) has refused to move cannabis to a less restrictive schedule, while allowing a synthetic form of the primary psychoactive substance (THC) in cannabis to be placed at a less restrictive level. Cannabis (marijuana) and natural THC (the primary psychoactive substance in cannabis) remain in Schedule I, while dronabinol (Marinol®), the synthetic form of THC, has since been reassigned to Schedule III (less controlled and more available) due to its safety and lack of activity as a “diverted” drug. In 1999, at the request of the White House, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) completed an 18-month study on therapeutic cannabis (Joy, Watson, & Benson, 1999). The study team found that cannabis is not highly addictive, is not a “gateway” drug, and has therapeutic value. It recommended that until pharmaceutical grade products become available, cancer and AIDS patients should be allowed to smoke the crude plant material for up to 6 months. The IOM also recommended that physicians should be able to conduct “N-of-1” studies on the patients whom they believe could benefit from cannabis and that research should be conducted on alternative delivery systems. This report has largely been ignored by the federal government, but research is going forward on the therapeutic use of cannabis in the United States and other countries. Despite the barriers and social bias against cannabis, 14 states have passed laws permitting the medical use of the drug. However, in June 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that federal authorities have the power to prosecute individuals for possession and use of medical marijuana even in the states that permit it (Tierney, 2005). How did this once-legal drug become the socially shunned problem child of the pharmaceutical industry and a political hot potato? The saga of cannabis in the U.S. health system is a story of the clash of politics, opinion, fear, emotion, and science. Prior to the U.S. Congress passing the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, cannabis was a medicine commonly used by physicians for a variety of ailments. Originally Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica plant material were imported to this country for use in medical products. As time went on, Cannabis americana was grown in the U.S. to provide access to fresh plant material to avoid the degradation that occurred when it was brought overseas on slow-moving ships. Cannabis tinctures (Figure 45-1), elixirs, salves, and even smokeable products were available. It was listed in the U.S. Pharmacopoeia until 1940. After Prohibition (the U.S. alcohol prohibition in the 1930s) ended in failure, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs and its leader, Harry Anslinger, needed to find something for the department to do or it would be dissolved. Anslinger targeted a drug used by “Negro” jazz musicians in the American South and Mexicans in the Southwest. The drug was cannabis, but was called reefer by the African-American population and marijuana (or marihuana) by the Hispanic population (Box 45-1). In 1936, the film Reefer Madness was released (a reefer being a marijuana cigarette) to warn the American population of the dangers of using marijuana. The film’s plot involves tragic events that ensue when high school students are lured by drug pushers into using marijuana. A “Reefer Madness” mentality was adopted by some government agencies, individuals, and media moguls like William Randolph Hearst. Few people realized at the time that this dangerous “new” drug was the same as the cannabis medicine that physicians prescribed. In the early 1980s, I was working in a small hospital in Washington state, when the Director of Nursing approached me with a problem. A cancer patient was going to be admitted who had experimental “marijuana” pills from the University of Washington. What should we do? I suggested we lock it up in the narcotics cabinet and dispense it as prescribed. No problems were encountered, and I began learning about Marinol® (Figure 45-2), the synthetic “marijuana” pill. At about the same time, I came across a flyer about an organization called the Alliance for Cannabis Therapeutics (ACT). It was started by a glaucoma patient, Robert Randall, and his wife. In 1976, Randall had gained legal access to federally grown marijuana under the Compassionate Use Investigational New Drug (IND) program following a series of court battles because no other medicine could control his intraocular pressure. He formed ACT, a nonprofit organization, to let others know about the therapeutic benefits of cannabis and how patients could get a legal, federally-approved supply of it. I was drawn to the issue. After moving to Ohio to complete graduate school at Case Western Reserve University in 1983, I conducted a survey on marijuana disclosure to health care professionals using the membership of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) as my survey population (Mathre, 1985). The thrust of my thesis was to determine if health care professionals asked patients about the use of cannabis and whether or not the survey subjects would disclose their use patterns. I received some surprising responses that led me to consider the therapeutic potential of cannabis. In a final question that asked the subjects to identify their concerns regarding the use of cannabis from a list of health problems, numerous respondents noted in the “other” option that they used it as medicine for stress, migraines, spasticity, pain, and other ailments (Mathre, 1988). I accepted the position of Director of the NORML’s Council on Marijuana and Health. By 1990, there were five patients who had legal access to marijuana through the Compassionate IND program. I was serving on the planning committee for the annual NORML conference and suggested that we have the patients present their cases in a panel presentation. The patients were eager to tell their stories and were excited to meet others with similar issues. Their presentations were aired on C-SPAN and garnered national attention. We had each patient interviewed and videotaped by a volunteer professional videographer. Over the next 2 years, excerpts from the interviews were used to create an 18-minute video called Marijuana as Medicine (Byrne & Mathre, 1992), which was designed to be a teaching aid. Following the airing of the patients’ panel, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) received many requests for IND access to marijuana, especially from HIV/AIDS patients. The Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Dr. Louis Sullivan, responded by shutting down the IND access to marijuana in 1992. At that time, 15 patients were receiving marijuana, over 30 patients had been approved and were waiting for their medication to be delivered, and hundreds of applications were waiting for review (Randall & O’Leary, 1998). Only the 15 current patients would be allowed to continue in the program, closing the door to all others. Also at this time, one of the legal patient’s supply of marijuana was cut off. Corinne Millet, a widow and glaucoma patient, sought help from her congressman to regain her supply of medicine, but during the 6 weeks she spent without her medication, she lost 80% of her peripheral vision (Byrne & Mathre, 1992). These events made me feel that it was important to end the prohibition on the use of cannabis in the U.S. My perspective was that there was no justifiable reason for the marijuana prohibition. It has therapeutic value, it is safe, and patients benefit from it. I saw this as a problem that required patient advocacy and that had ethical implications. I believed it to be a professional responsibility to end the cannabis prohibition and make this medicine legally available to patients. The more I learned, the more determined I became. I embarked on a more than 20-year fight, met countless barriers, and often felt like David taking on the Goliath of the federal government. Colleagues have questioned me over the years as to why I’m still trying to change the laws, but the answer is always the same: Patients still do not have access to a safe and legal supply of this medicine. Over the years, I’ve encountered many barriers and tried various strategies; often the same strategies have been used under different circumstances. Barriers that I’ve encountered include misinformation presented as facts, censorship of information, intimidation, laws and regulations that prevent research, an image based on racism and ideology rather than science and reality, and pharmaceutical industry pressure to prevent potential competition. I’ve used strategies such as finding a strong mentor; building a support system; mobilizing grassroots support; reframing the problem; partnering with patients; building a coalition; starting a nonprofit organization; providing continuing accredited education for health care professionals about cannabis; using the Internet effectively; playing by the government’s rules; teaching others; conducting research, disseminating research findings; and educating the public through publications, the press, and the media. In the years following the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, cannabis was removed from the U.S. Pharmacopoeia, it was no longer included in medical school curricula, and health care professionals learned about marijuana only in the context of substance abuse. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 further condemned the drug when officials wrongly, in my opinion, placed marijuana in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Schedule—the category of drugs that are highly addictive, are not safe for medical use, and have no therapeutic value (Box 45-2).

Taking Action

Reefer Madness: The Clash of Science, Politics, and Medical Marijuana

A Drug with An Image Problem

Once Upon A Time,Cannabis Was Legal

How and Why Did the Prohibition Begin?

The Descent into “Reefer Madness”

My Introduction to the Problem of Medical Cannabis Use

An Opportunity for Education

Barriers and Strategies

Hiding the Truth

Taking Action: Reefer Madness: The Clash of Science, Politics, and Medical Marijuana

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access