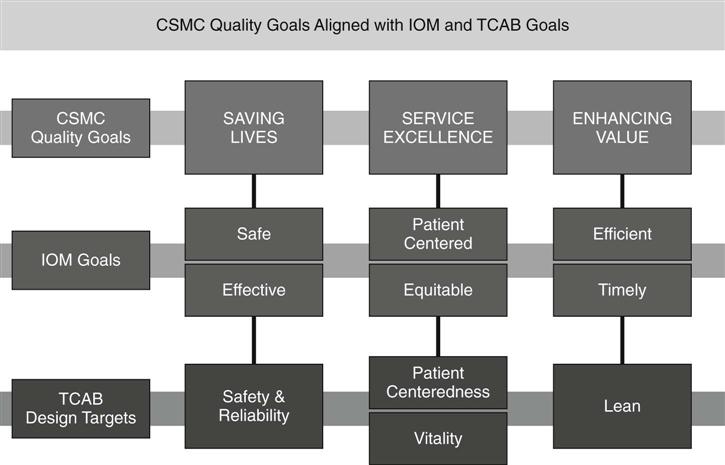

Linda Burnes Bolton and Margaret L. McClure “Quality is the result of a carefully constructed cultural environment. It has to be the fabric of the organization, not part of the fabric.” —Phillip Crosby All Americans should be afforded accessible care that is safe and of high quality. But what does this mean? We should be able to rely on our health care system to provide care for us that will not end up making us sicker. The 2001 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, admonishes us to create a system that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. To achieve these aims, the IOM report called for fundamental redesign of care systems. Getting there is not easy. Nursing care is central to how better outcomes might be achieved. Inadequate nurse staffing has been linked to adverse outcomes, which increase the length of stay, sometimes significantly (Aiken, 2002). When the stay is lengthened, so is the cost. Five adverse events—medication errors, falls, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and pressure ulcers—all associated with nursing care, were found to increase the cost of a hospital “case” by between $25 and $2384 (Pappas, 2008). The 2004 IOM report, Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses, noted that “research is now beginning to document what physicians, patients, other health care providers, and nurses themselves have long known: how well we are cared for by nurses affects our health, and sometimes can be a matter of life or death” (IOM, 2004). We must ensure that nurses are given the support they need to help prevent the enormous burden of medical errors and provide a patient-centered environment that is conducive to healing. Nurses must be empowered in their workplaces to proactively redesign work processes to achieve better clinical outcomes. To create this kind of active engagement, nurses must believe that their expertise is valued, know that they have a say in decisions, and be encouraged to lead and collaborate in quality improvement activities. By becoming an active participant in developing, implementing, and measuring the value of quality improvement activities, nurses have the opportunity to lead the way to better care. The following growing evidence shows that they can and will do so: • Donahue (2009) saw a “consistent and sustained improvement in patient satisfaction scores” following the engagement of staff in a performance improvement effort. • A nurse-led interdisciplinary team reduced falls among pulmonary rehabilitation outpatients by brainstorming ideas for improvement (Zant, 2009). • Rutherford and colleagues (2009) found that ten facilities engaged in Transforming Care at the Bedside (TCAB) demonstrated improvements making care safer and more reliable and with better teamwork and staff vitality. TCAB, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) was designed in 2003 to engage and empower nurses and other front-line providers to: improve the quality and safety of patient care on medical-surgical units, increase the team vitality and retention of nurses, improve patient’s and family members’ experience of care, and improve the effectiveness of the health care team. Initial TCAB hospitals served as laboratories for innovation and change on medical-surgical units with a focus on improving patient care outcomes and the work environment for nurses and the health care team. TCAB nurses regularly proposed solutions that might address either team vitality, patient-centered care, a safety issue or eliminating system “waste.” TCAB teams built knowledge and confidence in their redesign efforts by locally creating and testing new ideas, measuring outcomes, and implementing successful changes on their medical and surgical units. A national learning community was created through site visits, teleconferences, and face-to-face meetings where collaborative learning thrived among front-line staff, midlevel managers, hospital executives, and nursing faculty. This community reinforced learning and became the force behind the significant replication of TCAB. TCAB continues through collaboratives led by the American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE), through learning and innovation communities in IHI’s IMPACT Network, and within RWJF’s Aligning Forces for Quality initiative (Box 54-1). Hundreds of hospitals have now adopted TCAB as a way to deliver high-quality and safe patient care. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center actively pursued participation in the launching and implementation of the TCAB initiative. The opportunity to partner with two of the most important organizations committed to improving health care—the RWJF and the IHI—was irresistible. Our missions are aligned, and our values are similar. It was a match that would benefit all three and lay the foundation for fundamental change in acute care. Cedars-Sinai was chosen to be one of the initial pilot organizations. It is one of several U.S. institutions that have achieved both Magnet and Leap Frog status. The operating premise was to select diverse institutions and determine if the application of an idealized design created by the IHI would be effective in different settings. The IHI Idealized Design Process is a collaborative among various institutions to design and implement comprehensive system redesign (Moen, 2002). Our acceptance of the invitation to participate was considered by our president, trustees, senior executives including the chief nursing officer (also known as the C-Suite for the CEO, COO, CFO, or CNO), nursing leadership, and staff. We had the opportunity to further our goals and values of clinical excellence, defined as quality and innovation; service excellence defined as extraordinary patient, employee, medical staff, community, and volunteer experiences; and value defined as the best processes at the right price, without waste. We began by identifying two units and engaging the nursing director, manager, physician leader, education institution representative, patient representative, community service representative, and clinical leaders from across the organization. Cedars-Sinai had previously been engaged in a patient-focused care initiative led by the chief nursing officer. We had established solid liaisons with departments providing services to support the delivery of patient care and with physicians and education partners. We built on that foundation by calling together diverse voices to imagine the perfect work environment. We held a series of sessions to identify the “as-is states” of our environment, using a combination of the TCAB brainstorming techniques called deep dives and snorkels, as well as Technology Drill Down (TD2) strategies (Burnes Bolton, Gassert, & Cipriano, 2008) created by the American Academy Nursing. The TD2 process engages multiple stakeholders to describe their existing workflow practices, create a preferred state, and identify technology solutions to close the gap between the desired state and existing practices. Throughout the initial forming and storming period that lasted over 8 months, we had many opportunities to walk away, but we remained committed to the TCAB and institutional goals that were fully aligned, as shown in Figure 54-1.

Taking Action

Aligning Care at the Bedside with the C-Suite

Case Study

Beginning

Forming and Storming

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access