Barbara Davies, Dominique Tremblay, and Nancy Edwards

- Sustainability of evidence-based practice is a vital consideration to maintain or increase improvements in the provision of quality health care and patient outcomes and to avoid erosion or decay of a practice.

- Evidence-based practices require ongoing attention to changes in an organization or practice setting as well as watchful monitoring for new evidence and priority outcomes.

- The National Health Service sustainability model includes 10 factors clustered around the dimensions of process, staff, and organization. Other determinants include the political and power dimension, the need for priority setting, and a common language for stakeholders.

- Emerging promising practices for sustainability include a “yes we can attitude,” individual and collective reflective practice, leadership, and performance evaluation.

Introduction

This chapter includes definitions and models about sustainability to assist health care providers and decision-makers to design and sustain evidence-based practice (EBP) and measure its ongoing impact. Five strategies based on the literature and our experience for attaining more sustainable EBP are outlined: developing a “yes we can” attitude; interprofessional reflective practice; individual, multilevel, and collective leadership; evidence generation and use; and performance evaluation. The creation of broad-based indicators to support and measure the sustainability of health care changes are emphasized along with quantitative, qualitative, and participatory approaches to evaluation. Two exemplars are described to illustrate issues and approaches to sustainability planning in cancer care and long-term database development in perinatal care. Future recommendations for sustainability-oriented EBP and research are described.

The need for and concept of “sustainability” of EBP change

Efforts to sustain the implementation of EBP changes are imperative; otherwise any improvements made to practice by health care providers may be lost after the completion of a project (Argentine Episiotomy Trial Collaborative Group 1993). Sustainability is defined as “the degree to which an innovation continues to be used after initial efforts to secure adoption are completed” (Rogers 2003) or “when new ways of working become the norm” (Maher et al. 2007). In order to prevent the fading or decay of short-term improvements, it is vital to continue to maintain or adapt an EBP and to evaluate its integrity and sustainability. There are no quick fixes for dealing with sustainability. A “vigilant diagnostic approach” to monitoring both supporting and threatening factors over the time period when the EBP should be encouraged is recommended (Buchanan et al. 2007: p. 23.)

Maintaining the integrity of EBP

Adaptation due to changes in the organization

Maintaining the integrity of an EBP and the active ingredients of what make an EBP work is straightforward when the situation remains constant. However, in health care systems, change is the norm with the dual dynamics of changes in both organizational factors and the emergence of new evidence. With respect to the organizational perspective, factors such as the availability of new types of health care providers or availability of new equipment may influence the integrity of an EBP. Thus, from a sustainability perspective, it is highly likely that adaptation of an EBP will be required over time. Periodic evaluations will be important to determine whether subsequent organizational modifications or changes in the practice environment influence use of an EBP and whether this positively or negatively has an impact on outcomes. For complex interventions, it is recommended that the function and process of an intervention be standardized but not the specific components (Hawe et al. 2004).

For example, with respect to the provision of continuous support for women during childbirth, a meta-analysis of 16 trials involving 13,391 women in 11 countries found that women randomized to receive continuous support were more likely to have spontaneous vaginal births and were less likely to report dissatisfaction with their childbirth experiences (Hodnett et al. 2007). Of note was that support appeared to be more effective when provided by women who were not part of the hospital staff. The active function and process ingredients of this complex intervention are the theory-based aspects of the provision of emotional support, comfort measures, information and advocacy. Specific support behaviors are tailored to an individual woman’s context, such as her culture, attendance at prenatal education, and other available support from a spouse or family member. The meta-analysis concluded that “all women should have support throughout labour and birth” yet it is still evident that “in hospitals worldwide that continuous support during labour has become the exception rather than the routine” (Hodnett et al. 2007).

Maintaining the integrity of an EBP such as the provision of continuous support for women during childbirth is influenced by organizational barriers such as the use of a unit’s central fetal monitoring system, which encourages charting and monitoring outside of the woman’s room (Graham et al. 2004). Thus, we recommend that care providers and decision-makers regularly consider organizational factors that may influence the active ingredients and the integrity of EBP. As stated by Denis et al. (2002), complex interventions are not a “thing” with fixed boundaries but include a “hard core” of its irreducible elements (e.g., elements of the provision of support during labor) and a “soft periphery” of the structures and systems that need to be in place for sustainability.

Adaptation due to the emergence of new evidence

Ongoing systems are required to inform health care providers and decision-makers about new evidence and EBPs, so that they can selectively apply, adapt, or discontinue the implementation of an EBP. For example, the ongoing “sustained” implementation of an outdated clinical best practice guideline is not advisable. Systems need to be put in place to find and appraise the results of promising new research evidence; retrieve and appraise new and updated guidelines; examine patient preferences for EBP options; obtain input about clinician’s experiences implementing guidelines; and learn about other emerging EBPs and contextual influences. A leader from a high-performing health care organization explains that sustainability is a challenge because their “just do it culture” results in many concurrent improvement activities (Baker et al. 2008). This leader also highlights that there is “a continuing need to prioritize project commitments systematically, to divest those projects that produce marginal outcomes and to complete priority projects before engaging in new ones” (Baker et al. 2008: pp. 260–261). This quote illustrates that health care providers and leaders need to be active and not passive recipients of new evidence (knowledge) and need to collectively determine the relative advantage of new EBP. From a sustainability perspective, selective monitoring of priority outcomes of concurrent initiatives as well as previously established EBP is required.

Sustainability models

Although 11 of 31 models about knowledge translation describe a separate step subsequent to evaluation entitled maintaining change or sustaining ongoing knowledge use (Graham et al. 2007), very few studies have been conducted about the determinants of sustainability. Only 2 of 1000 sources screened in a systematic review of the diffusion of innovations in health services organizations mentioned the term sustainability (Greenhalgh et al. 2005). Furthermore, sustainability is not a common key word indexed in evidence-based textbooks such as Evidence-Based Nursing (DiCenso et al. 2005) or Using Evidence (Nutley et al. 2007). However, the term sustainable is frequently used by policy-makers and politicians in Canada, UK, USA, and other countries as they strive to develop and maintain “sustainable” health care services and programs for the public.

Priority setting for sustainability

How might priorities be set from a sustainability perspective? One research team has recently proposed a new priority setting conceptual framework to help address the complex decision-making required to sustain health care systems that are constantly challenged by increasing service demands and new technology (Sibbald et al. 2009). The framework was derived from three empirical studies and is intended for decision-makers of clinical programs, hospitals, regional authorities, or governments. The framework includes 10 elements in two clusters of process and outcome concepts. The process concepts are stakeholder engagement, use of explicit process, information management, consideration of values and context, and revision or appeal mechanisms. The outcome concepts are improved stakeholder understanding, shifted priorities and/or reallocated resources, improved decision-making quality, stakeholder acceptance and satisfaction, and positive externalities (e.g., media and accreditation). This model is useful because it articulates defined process outcomes, acknowledges the importance of values and context, and provides a common language for stakeholders to discuss contentious issues. However, the model does not include the measurement of health outcomes such as morbidity, mortality, quality of life, or patient/client satisfaction. How will decision-makers and health care providers decide when health outcomes are marginal or when to stop an EBP and test out a new approach? Ongoing evaluation of this promising priority setting model with concurrent health outcome analyses is a potential area of research.

The NHS sustainability model

Despite the limited research about sustainability, the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK has been a leader in the codevelopment of a sustainability model with and for the NHS by frontline teams, administrators, and experts from industry and academia (Maher et al. 2007). The model was developed using a multifaceted approach based on the change management literature, and an analysis of focus group discussions with health care experts and 250 NHS staff (Maher et al., personal communication). Initially, over 100 factors were identified. Subsequently these factors were ranked and regression analyses were conducted to develop a predictive scoring system. To date, the authors report receiving extensive feedback about the utility of the model, which is currently being used in a US-based study (Maher et al., personal communication).

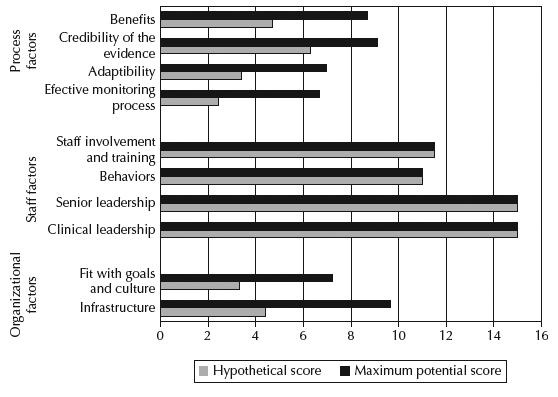

The model includes 10 factors clustered in three major dimensions of process, staff, and organization (Maher et al. 2007). A strength of this model is that is includes the measurement of health outcomes as an important factor, a limitation of the previously described priority setting model (Sibbald et al. 2009). Developers suggest that this model is useful for planning specific sustained EBP changes at the team, organizational or community level. Using the model during the initial implementation process is recommended by the authors to avoid sustainability failure, which is estimated at 33% for health care initiatives and 70% for organizational changes (Maher et al. 2007). The model can be used as a diagnostic tool to identify potential barriers to sustainability. A leaders’ guide is available which describes practical tips (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2007). An excel spreadsheet can readily be downloaded at no cost from the National Leadership and Innovation Agency for Healthcare in the UK (2009) to assess factors thought to influence sustainability. The following list includes the NHS model elements and their corresponding indicators for self-assessment by leaders and teams attempting to design sustainable health care change. Further details to assess each indicator are included in the model and guide. In the following section, each indicator is described, as quoted from Maher et al. (2007).

Process factors

- Benefits beyond helping patients: The change improves efficiency and makes jobs easier

- Credibility of the evidence: Benefits of the change are immediately obvious, supported by evidence and believed by stakeholders

- Adaptability of improved process: The process can be adapted to other organizational changes and there is a system for continually improving the process

- Effectiveness of the system to monitor progress: There is a system in place to identify evidence of progress, monitor progress, act on it and communicate results

Staff factors

- Staff involvement and training to sustain the process: Staff have been involved from the beginning of change and adequately trained to sustain the improved process

- Staff behaviours toward sustaining the change: Staff feel empowered as part of the change process and believe the improvement will be sustained

- Senior leadership engagement: Organizational leaders take responsibility for efforts to sustain the change process, Staff generally share information with, and actively seek advice from, the leader

- Clinical leadership engagement: Clinical leaders take responsibility for efforts to sustain the change process, Staff generally share information with, and actively seek advice from, the leader

Organizational factors

- Fit with the organisation’s strategic aims and culture: There is a history of successful sustainability and improvement goals are consistent with the organizations strategic aims

- Infrastructure for sustainability: Staff, facilities and equipment, job descriptions, policies, procedures and communication systems are appropriate for sustaining the improved process

The NHS model developers recommend that teams concentrate on factors with lower scores and thus room for improvement. Figure 9.1 displays an example of hypothetical scores for sustainability factors. The hypothetical data indicate that the score for the factor “effectiveness of the system to monitor progress” was low. In this scenario, teams, providers and stakeholders should identify relevant data, access the data and communicate the results to patients/clients, staff and the regional or national health care system.

Future research needs to test the relative weights of this scoring system in different applications and settings and to prospectively study whether the implementation of sustainability action plans arising from an assessment using the model, improves success rates and outcomes. However, sustainability planning is only one important aspect. The ongoing adaptation of EBP that is required due to organizational changes and new emerging evidence is perhaps the more urgent research needed since it is disheartening for clinicians, managers, and senior administrators to see erosions in health care after successful changes were made in short-term EBP projects. Future research needs to test whether or not this NHS sustainability model or a priority setting sustainability framework or a combination of models improves and sustains outcomes over the long term.

Figure 9.1 Score for the elements of the NHS sustainability model—using hypothetical data in an accessible excel spreadsheet from the UK National Leadership and Innovation Agency for Healthcare.

Adapted from Maher et al. (2007); http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/829/page/36527.

It is interesting to review the scoring mechanisms of the NHS sustainability model and note that the potential for the highest scores as ranked by the experts and focus group participants (Maher et al. 2007) are for the senior and clinical leadership dimensions of the model. These higher proposed scores for leadership are consistent with the results of a Canadian study to determine factors related to the sustained implementation of nursing guidelines (Davies et al. 2006). Leadership, defined as “recognizable role models, leaders, champions or administrative support,” was the only significant predictor explaining 47% of the variance of how strongly a guideline permeated the organization 2 years after the original implementation (Davies et al. 2006). Examining the critical factors apparent in sustainability failures is just as important as determining the factors in successful sustainability. With respect to the previously mentioned nursing guideline implementation study, we found that in the 16 health care organizations that did not sustain guideline implementation, that there was no ongoing staff education and no integration of the guideline recommendations in policies, procedures, or e-documentation. Of note, these two factors are also identified within the 10 key factors in the NHS sustainability model. Staff education is labeled as training and involvement where as policy/documentation is labeled as infrastructure (Maher et al. 2007).

One other variable that is not explicit in the sustainability model but that has been reported in the literature is the political and power dimension (Buchanan et al. 2007; Davies & Edwards 2009). Attention needs to be paid to the power, influences, and support of stakeholders (Edwards & Roelofs 2006). The need for “intense” sustainability efforts that can buffer changing political and economic factors has been described graphically by a leader of a high-performing health care organization as “hurricane-proofing the change initiatives to protect against the inevitable next cycle of budget reductions and staff cuts” (Baker et al. 2008: p. 205).

Strategies for more sustainable EBP

While models for sustainability provide useful guidance to plan for the implementation of future EBP, there are also some emerging promising practices. In this section we describe specific evidence-based strategies for sustaining EBP improvements.

(1) Developing a “yes, we can attitude”

The importance of rhetoric and opinion leaders’ positive discourse has been found to play a central role for innovation to succeed (Akrich et al. 2002). This positive approach highlights the necessity to use strategies beyond “barriers management” that has been a major focus in the EBP literature. A barriers-oriented approach can lead to inertia (Marchionni & Richer 2007), particularly if there are long-standing issues. Improving sustainability requires building positive thinking and celebrating small wins through a stepwise evolution. Appreciative inquiry is a social process that builds a positive dialogue among stakeholders to rediscover their aspirations and to use these aspirations to reach collective goals (Cooperrider & Whitney 2000). Appreciative inquiry has been described as a change philosophy that shifts the discourse from a focus on deficits to an emphasis on the potential of individuals and organizations (Lind & Smith 2008). The appreciative approach offers a capacity-building orientation to implementing EBPs, which may be a stimulus for sustained improvement.

(2) Interprofessional reflective practice

Based on largely theoretical evidence (Duffy 2007; Mann et al. 2007), there is a growing body of literature suggesting pragmatic linkages between reflective practice and long-term EBP (Mantzoukas & Watkinson 2008; McWilliam 2007; Paget 2001; Rolfe 2005; Watkins et al. 2004). Reflective practice is the act of interrogating the efficacy of daily practice to learn from professional experience (Schön 1983). Reflective practice is both an individual and a collective action that introduces a mode of being aware of the strengths and weaknesses of practice. This approach has been credited with empowering the practitioner to enact desirable and effective practice (Duffy 2007; Sandywell 1996). Reflective practice discussions provide a deliberative forum for clarifying, analyzing, and using evidence. EBP and reflective activities increase sustainability in creating a space for appropriation of new knowledge as an emerging internal process rather than an imposed external innovation. The former provides the foundation for research-based clinical practice and the latter allows the professional assessment and reassessment of clinical EBPs and routines. As professionals are more receptive to innovation emerging from their internal dynamics rather than those imposed by an external imperative (Ferlie et al. 2005), EBP and reflective practice create the synergy for sustainable change “integrating science push and demand pull” occurring within the process of social interaction (McWilliam et al. 2009: p. 7).

(3) Leadership: Individual, multilevel, and collective

The literature on innovation clearly demonstrates the importance of individual leadership for EBP implementation (Akrich et al. 2002; Berwick 2003; Rogers 2003). Even with the scarcity of research about the determinants of sustainability, we can anticipate that leadership is a cornerstone for sustained EBP. Indeed, in a secondary analysis of qualitative data to investigate factors that contributed to sustaining (or not) the use of clinical guidelines in professional nursing practice, a different pattern of leadership was found in organizations that sustained guideline implementation (Gifford et al. 2006). Three broad leadership strategies emerged as central to successfully implementing and sustaining guidelines in nursing: (1) facilitating individual staff to use the guidelines, (2) creating a positive milieu of best practices, and (3) influencing organizational structures and processes (Gifford et al. 2006). Specific leadership activities included providing support, being accessible and visible, communicating well, reinforcing goals and philosophy, influencing change, role modeling commitment, ensuring education and policy, monitoring clinical outcomes, and supporting the development of clinical champions. This study illustrates the importance of leaders’ multilevel involvement to support sustained behavior change for professional practice.

From a broader perspective, focusing on health system pluralism, the dynamics of collective leadership could appear to be a master piece for sustainable EBP change. Pluralistic organizations are characterized by multiple objectives with competing values, diffuse power and knowledge-based work processes (Denis et al. 2007). The complexity of pluralistic organizations calls for the development of unified collective leadership rather than individuals imposing separate visions for EBP.

(4) Evidence and sustainability

The approach used to generate and apply evidence to health care systems may contribute to enhanced use of evidence by decisionmakers (Glasgow & Emmons 2007; Landry et al. 2003). EBP sustainability initiatives need to address the limitations of linear (A → B) diffusion models. Evidence production and use involves different networks of health care providers, each having their own values, interests, priorities, dynamics, means of communication, objectives, and boundary management (Best et al. 2008). We suggest that evidence application that spans traditional boundaries for health care delivery may not only support sustained use of evidence, but also generate new evidence gaps that will need to be addressed by teams of researchers who are also willing to cross their network boundaries. Research priorities identified considering contextual factors may be more likely to reflect the complexity of the practice environment, yielding health services research that is more relevant for decision-making and interprofessional practice (Glasgow & Emmons 2007).

(5) Performance evaluation

Performance evaluation has a role to support change and ensure sustainability (Potvin & Golberg 2006). A broad-based approach is recommended to identify and measure the wide range of impacts that EBP may have at a particular level of a health care system (clinical, organizational, and governance). Indicator identification should occur before implementation begins. Sustainability indicators are essential building blocks in evidence-based planning, management, and monitoring processes.

Good sustainability indicators must be easy to understand, as well as clinically and economically feasible to measure. Based on our experience and the literature, some of the benefits from developing and using good indicators include:

- More timely decision-making, which may help reduce risks and/or costs,

- Identification of emerging risks and or conflicting issues that may compromise sustainability,

- Identification of impacts, to allow for timely corrective action when needed,

- Setting clear benchmarks for ongoing performance measurement,

- Greater public accountability, that is, providing credible information for the public and other stakeholders,

- Providing the means to monitor for continuous quality improvement,

- Earlier identification of unanticipated adverse effects or unexpected benefits, thus identifying limits and opportunities.

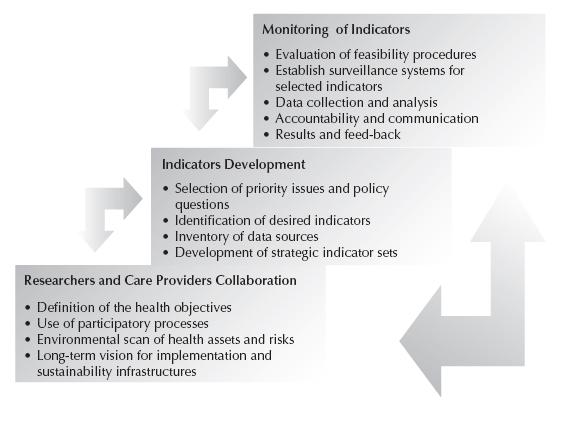

A suggested development process for indicators that will be sustainable

At the outset, it is important to recognize that different levels of health indicators are required for health planning and regulation processes. For example, system-level cancer care performance indicators in Ontario, Canada, were developed in the context of a longstanding health strategy and planning process based on best-available evidence (Greenberg et al. 2005). In this case, focusing on sustainability indicators can help improve data sources, monitoring functions, and reporting processes. Literature on the sustainability of innovation and performance in health services (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2008; Baker et al. 2008; Greenberg et al. 2005; Pluye et al. 2004; Sicotte et al. 1998) suggests a step-by-step process to maximize the coherence among evidence, professional routines, and organizational culture. Based on this literature, we have generated Figure 9.2. This process for developing sustainable indicators is not linear. The fundamental base is the development of a collaborative approach between researchers and care providers followed by the identification of indicators and data sources. The third step concentrates on evaluation and feedback for practice adjustment.

Criteria for selecting sustainability indicators

The main criteria for selecting sustainability indicators in health should be:

- Relevance of the indicator to the selected issue for stakeholders’ long-term objectives,

- Feasibility of obtaining and analyzing the needed information in a way that informs timely decision-making in order to stabilize practice around the desired outcomes,

- Credibility of the information and reliability for users,

- Clarity and ability to be understood by users, and

- Comparability over time and across jurisdictions or regions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree