Christina M. Godfrey, Margaret B. Harrison, and Ian D. Graham

- Study outcomes reflect the effectiveness of implementation strategies.

- Diversity of outcomes and methods to measure them complicates comparison of implementation studies.

- Provider’s instrumental use of knowledge (action taken with the knowledge) is most frequently measured.

- Further research is needed on the impact of providers’ behavior indicating the effect at the patient level.

Research to determine the effectiveness of strategies to implement evidence-based practice (EBP) and enhance the quality of care is steadily increasing. However, to evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies we need to examine the outcomes that are measured as indicators of success or failure of these efforts. The variety of outcomes that are measured plus the diversity of methods used to measure these outcomes complicate comparison between implementation studies and may be hindering the adoption of strategies at the local level. We need to compare both intervention strategies and outcome measurements to make meaningful conclusions about which strategies or combinations of strategies can be relied upon to consistently and efficiently achieve successful outcomes.

This chapter focuses on the measurement of outcomes within the context of implementation research. Studies contributing to this context have investigated strategies for implementing clinical guidelines in practice. The current knowledge on guideline dissemination and implementation strategies indicates that there is no clear-cut formula, no specific strategy or even set of strategies that can be relied upon to successfully and consistently implement guidelines into practice (Grimshaw et al. 2004; Harrison et al. 2010). Examining the outcome measures used in practice guideline implementation studies offers insight into the diversity of outcome measurement in EBP and indicates the value and difficulty of comparing outcomes between implementation studies.

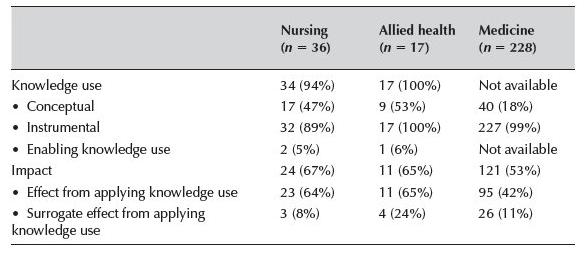

To explore outcome measurement we adopt the framework of knowledge use and its impact proposed by Graham and colleagues (see Chapter 2), and the categorization of methods of measurement proposed by Hakkennes and Green (2006). These approaches are examined using the outcome measures reported by two systematic reviews on implementing clinical practice guidelines in practice, using studies focused on nursing, allied health, and medicine (Grimshaw et al. 2004; Harrison et al. 2010). In this chapter we compare and discuss what outcomes were measured, how the outcomes were measured and illustrate differences with regard to these different professional groups (Table 10.1).

Method and background on the reviews

Grimshaw and colleagues (Grimshaw et al. 2004) performed a systematic review on the dissemination strategies to implement guidelines in medicine. Their comprehensive search of the literature (1966–1998) located 235 studies and included only the most rigorous research designs (randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, controlled before and after studies, and interrupted time series studies). Results from this review are taken from the included studies only, all of which report an “objective” measure of provider behavior. Survey-based measures at the level of provider (intention) are excluded from the review.

Table 10.1 Classification of outcome measures according to Hakkennes and Green (2006) and Graham and colleagues (Chapter 2)

Outcomes measures (Hakkennes & Green 2006: p. 3).

| Hakkennes and Green (2006) | Graham and colleagues (Chapter 2) |

| A. Patient level | |

| 1. Measurements of actual change in health status, i.e., pain, depression, mortality, and quality of life | Impact of knowledge use—Effect from applying the knowledge, i.e., changes in health status |

| 2. Surrogate measures of A1, i.e., patient compliance, length of stay, patient attitudes | Knowledge use—Instrumental, i.e., changes in patient behavior |

| B. Practitioner | |

| 1. Measurement of actual change in health practice, i.e., compliance with guidelines, changes in prescribing rates | Knowledge use—Instrumental, i.e., changes in practice, adherence to EBP recommendations |

| 2. Surrogate measures of B1, such as health practitioner knowledge and attitudes | Knowledge use—Conceptual, i.e., changes in knowledge, attitudes, intentions |

| C. Organizational or process level | |

| Measurement of change in the health system (i.e., wait lists), change in policy, costs, and usability and/or extent of the intervention | • Knowledge use—Surrogate measures of instrumental use, i.e., changes in policies, staffing, acquiring equipment • Impact of knowledge use—Effect from applying the knowledge, i.e., changes in expenditure, resource use, wait times, length of stay, visits to emergency department, hospitalizations and readmissions |

The outcomes measured by these studies were reanalyzed by Hakkennes and Green (2006: pp. 3,4) and allocated to nine categories of outcome measurement:

- Medical record audit,

- Computerized medical record audit,

- Health practitioner survey/questionnaire/interview,

- Patient survey/questionnaire/interview,

- Computerized database (pharmacy prescription registers; medical billing information),

- Log books/department record/register (emergency department visit records; log books of X-ray requests),

- Encounter chart/request slips/diary (data collection forms designed by the study and completed by practitioners; diaries for study data collection),

- Other (laboratory tests, audio/video taping of consultations), and

- Unclear (method of measurement not clear).

Hakkennes and Green (2006) also categorized the studies according to those that measured patient outcomes (n = 155); provider outcomes (n = 242), and system outcomes (n = 87).

In a similar fashion, the systematic review performed by Harrison and colleagues (2009) focused on the guideline dissemination and implementation strategies in nursing and allied health professions. Their expansive search of the literature (1995–2007) located 53 studies (36 nursing, 17 allied health). They also included only the most rigorous research designs (randomized controlled trials and controlled before and after studies). Included studies in this review report both “objective” measures of provider behavior as well as intention to act. The outcomes measured by these studies were analyzed according to the nine categories proposed by Hakkennes and Green (2006), and tallied into patient outcomes (nursing: n = 15; allied health: n = 8); provider outcomes (nursing n = 30; allied health: n = 16); and system outcomes (nursing: n = 11; allied health: n = 9).

The outcomes of both reviews were then classified according to the categories of knowledge use or the impact of knowledge use. Knowledge use is divided into conceptual use which refers to the knowledge, attitudes, or intensions; and instrumental use which refers to behavior based on that knowledge. Impact of knowledge use is divided into direct effects resulting from applying the guidelines, such as changes in health status (patient) or changes in quality or continuity of care (provider); and surrogate effects of applying the guidelines, such as changes in return to work status (patient) or changes in job satisfaction (provider). Information from guideline implementation studies in medicine was obtained from the published data reported in the study by Hakkennes and Green (2006); however, in some cases, data from this study were not directly comparable or available. In these instances comparison is made between nursing and allied health and the lack of data for medicine is noted.

Knowledge use and impact of knowledge use

In keeping with Graham and colleagues’ framework (see Chapter 2), we distinguish between the use of knowledge and the impact of knowledge use. For example, measuring a provider’s knowledge about pain management would be a measure of conceptual knowledge use (not action). Assessing the extent to which providers’ follow pain guideline recommendations about pain assessment and management (i.e., adhere to the guideline) would be a measure of instrumental knowledge use (action, and behavior). Measuring a change in the patient’s pain (i.e., assessing the effect of the pain management on that patient’s pain) would be a measure of the impact of using the guideline. If the patient is pain free and consequently is able to return to work or to remain at work for several hours, this would be a measure of the surrogate effect of applying the guideline.

For nursing and allied health professions, many more of the guideline implementation studies reported knowledge use as an outcome measure compared to the impact of knowledge use (Table 10.2). Ninety-four percent of nursing studies and 100% of allied health studies measured change in terms of knowledge use compared to 67% and 65% for impact of knowledge use respectively. For the studies in medicine, no data were available on the overall proportion of studies that included a measure of knowledge use; however, 53% of the studies measured impact of knowledge use.

Table 10.2 Proportion of guideline implementation studies with knowledge or impact outcome measures by profession

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree