Ian D. Graham, Debra Bick, Jacqueline Tetroe, Sharon E. Straus, and Margaret B. Harrison

- Consideration and measurement of instrumental, conceptual, and symbolic use of knowledge are important considerations in implementation research.

- Measurement of knowledge use depends on one’s definition of knowledge, of knowledge use, and on the perspective of the knowledge user.

- Evaluation of knowledge use can be complex, requiring a multidimensional and iterative approach, focusing at the patient, provider, and system-level outcomes where appropriate.

- A clear starting point in this work is to define the outcomes of interest and to clearly distinguish between consideration and measurement of knowledge use and consideration and measurement of the impacts that knowledge use has on service users/patients, providers, and the health system.

Introduction

This chapter explores some of the conceptual and methodological issues related to measuring outcomes of evidence-based practice (EBP). EBP is a type of knowledge use, primarily knowledge derived from research. In keeping with many of the planned action models/theories (Graham et al. 2006), we divide outcomes into two broad categories: knowledge use (use of the evidence underpinning the practice, i.e., behavior change) and its impact (what results from use of that knowledge, i.e., service user/patient outcomes, improved, more efficient and cost effective delivery of care) and discuss some of the conceptual and measurement issues involved. The chapter concludes by considering how measuring outcomes of EBP can demonstrate return on investment in health research.

Knowledge use

Knowledge use should be monitored during and following efforts to implement EBP (Graham et al 2006). This step is necessary to determine how and to what extent the knowledge has diffused through the target decision-maker groups (Graham et al. 2006). Knowledge uptake is typically complex and examining attitudes and perceptions, and how and where evidence is integrated in decision making influences the success of implementation. It is also an important precursor to other outcome assessment to ensure any positive or negative effects that are attributed to the knowledge use and the main indicator of the success of an intervention to implement EBP. By monitoring knowledge use, identifying when it is sub-optimal and exploring the barriers and supports to knowledge uptake, action can be taken to refine the implementation intervention to overcome the barriers and strengthen the supports. Measuring and attributing knowledge use is still in its infancy within health research. How we proceed to measure knowledge use depends on our definition of knowledge and knowledge use and on the perspective of the knowledge user.

Several models or classifications of knowledge use have been proposed that essentially group knowledge use into three categories: conceptual (indirect), instrumental (direct), and symbolic (persuasive or strategic) use (Beyer & Trice 1982; Dunn 1983; Estabrooks 1999; Larsen 1980; Weiss 1979). Conceptual knowledge use refers to knowledge that has informed or influenced the way users think about issues (i.e., this includes the notion of enlightenment). Measures of conceptual use of knowledge include comprehension, attitudes, or intentions. Instrumental or behavioral knowledge use (Larsen 1980) refers to knowledge that has influenced action or behavior (i.e., direct application of knowledge that influences behavior or practice via incorporation into decision making). Measures of instrumental knowledge use include adherence to guideline recommendations as assessed by process of care indicators. Another form of instrumental knowledge use would include changing policy and procedures, acquiring necessary equipment, or reorganizing staffing or services to enable adherence to EBP (we label this type of knowledge use as enablers of instrumental use). The third category of knowledge use is often referred to as symbolic (persuasive or strategic) knowledge use (Beyer & Trice 1982; Estabrooks 1999; Weiss 1979). Symbolic use involves using research as a political or persuasive tool to legitimize and sustain predetermined positions. It is about using research results to persuade others to support one’s views or decisions and thereby may (or may not) lead to either conceptual or instrumental use of that knowledge by others. Symbolic use can be considered as an implementation intervention in some cases. Dunn further categorized knowledge use by describing that it could take place at the individual or collective level (Dunn 1983).

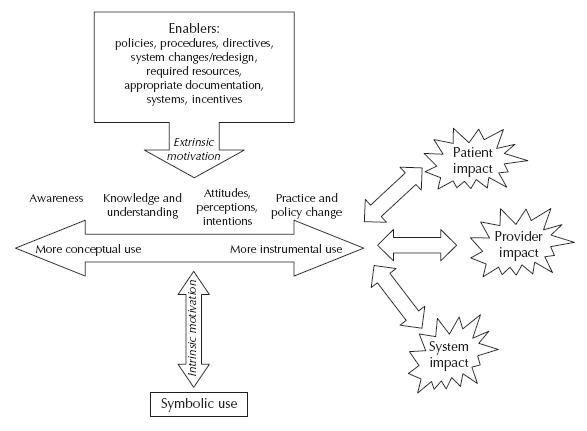

Building on the work of Nutley and colleagues (Nutley et al. 2007), Figure 2.1 depicts our conceptualization of the relationships between knowledge use and its impact. EBP has the potential to impact service user, provider, and system outcomes. Impacts result directly from instrumental knowledge use (applying EBPs) while the effect of conceptual use of EBP is usually through its eventual influence on instrumental use. Knowledge use can be seen as a continuum ranging from conceptual to instrumental use. Any effect of symbolic use of knowledge is mediated through its influence on either conceptual or instrumental use. Enablers of instrumental use create the preconditions that facilitate instrumental use directly (e.g., the adoption of a new policy requires a practice change or incentives are introduced to motivate behavior) and can also influence conceptual use as the individual comes to value the practice change they are required to perform. It should be noted that motivation for behavior change may be intrinsic (as is the case when conceptual use influences instrumental use because the individual believes performing the practice will be beneficial) or extrinsic (as is the case when enablers of instrumental use create the preconditions where behavior change results without the individual having to consciously think much about it, e.g., removing a particular test from a test ordering form).

Figure 2.1 Conceptualization of outcomes of evidence-based practice.

We find it useful to differentiate conceptual, instrumental, and symbolic knowledge use when planning and implementing EBP (Graham et al. 2006). As mentioned above, conceptual use of knowledge implies changes in understanding, attitudes, or intentions. Research could change thinking and be considered in decision making but not result in practice or policy change because the evidence is insufficient; change is not prudent at this time; current practice is close enough, etc. From an EBP perspective, the aim would be to have conceptual knowledge use become the impetus for instrumental use (i.e., a practitioner becomes knowledgeable about a best practice and develops both positive attitudes toward it and intentions to want to do it which in turn motivates action (instrumental use)). Instrumental knowledge use can, however, occur in the absence of conceptual use of that same knowledge, although this is sub-optimal. This is more likely to occur when there are strong incentives to adopt an EBP even when a practitioner may be sceptical or unaware of the underlying evidence for the practice or believe that it will not accrue its expected benefits. In cases such as this, the instrumental use of knowledge is extrinsically, rather than intrinsically, motivated.

An example of conceptual knowledge use comes from a study to increase maternity care nurses’ provision of labor support and diminish the use of continuous electronic fetal monitoring. In this study one outcome measure was nurses’ self-efficacy for labor support (Davies & Hodnett 2002). Nurses had high levels of self-efficacy related to the desired behavior of labor support, yet this was not correlated with their performance of labor support (instrumental use) (Davies et al. 2002).

Instrumental knowledge use is the concrete application of knowledge in practice that should result in a desired outcome (Graham et al. 2006). An example of instrumental knowledge use is when knowledge that has been transformed into a usable form such as a practice guideline or care pathway is applied to making a specific decision. In the Davies study (Davies et al. 2002), use was measured by the extent to which nurses actually provided labor support and the use of electronic fetal monitoring. Labor support was determined by using a work-sampling approach to measure the proportion of nurses’ time spent providing labor support with two independent observers randomly observing nurses during blocks of time and classifying nursing behaviors according to a structured worksheet (Davies et al. 2002). Frequency of use of electronic monitoring was measured by conducting an audit on randomly selected obstetric records. In both cases the measures provided an indication of instrumental use of the recommendations in the fetal health surveillance guideline of interest.

Symbolic knowledge use refers to research being used as a political or persuasive tool to influence others’ conceptual or instrumental knowledge use. Knowledge can be used symbolically to, for example, provide a scientific basis for a decision, but it can also be used symbolically to attain specific power or profit goals (i.e., knowledge as ammunition). Another example of symbolic use is for making decisions already taken seem to be evidence based (we call this “decision-based evidence making”). As a positive example, the knowledge of adverse events associated with use of mechanical restraints on agitated inpatients can be used symbolically to persuade the nursing manager on the medical ward to develop a ward protocol about their use. In this example, symbolic knowledge use facilitates understanding by the nurse manager of the issues around mechanical restraints (conceptual use) and prompts her to act (instrumental use).

Further justification for classifying knowledge use into conceptual and instrumental use comes from Grol and Wensing (2005) who reviewed 10 models and theories of stages or steps in the change process originating from different disciplines and revealed how remarkably similar they all were. When these stages are considered in the context of types of knowledge use, all the stages of change models differentiate between conceptual knowledge use—becoming aware of the innovation (e.g., stages labeled awareness, comprehension, seeking information), increasing one’s knowledge (stages labeled knowledge, understanding, skills), forming positive attitudes (stages labeled attitude formation, attitude change, agreement, positive attitude), developing intentions to use (stages labeled decision, intention to change), and instrumental use (initial and ongoing use labeled initial implementation, behavior change, change of practice and sustained implementation, consolidation, maintenance of change, routine adherence). Grol and Wensing’s own model of the process of change for care providers and teams consists of orientation (promote awareness, stimulate interest), insight (create understanding), acceptance (develop positive attitudes, a motivation for change, create positive intentions or decision to change), change (promote actual adoption into practice), and maintenance (integrate new practice into routines) (Grol & Wensing 2004). All of these models illustrate how knowledge use is conceptualized as a continuum running from awareness, understanding, attitudes, and intentions (conceptual use) through to practice and policy change (instrumental use).

Finally, it should be remembered that with all types of knowledge use, it may be complete or partial. Using the example of practice guideline implementation, the adoption of a guideline with multiple recommendations might result in conceptual use of some recommendations and instrumental use of others. Furthermore, instrumental use of the same guideline might involve intentionally disregarding some recommendations while adhering to others. This can be further complicated when adherence to some recommendations might be complete or partial. In other words, a clinician’s approach to recommendations in the same guideline could range from conceptual use of some of them (they understand the recommendation but do not adhere to it), partial instrumental use of some of them (they follow some of the recommendation but not all of it or are not able to follow all of them because of the circumstances of their practice setting) and complete instrumental use of others (they follow the recommendation to the letter).

Measurement considerations

When thinking about measuring EBP one needs to consider outcomes from several perspectives: definitional, approach to measurement, and selection of measures and tools. The operational definition of the outcome is a first step. This involves determining whether you are interested in measuring knowledge use (and within this broad concept—conceptual, instrumental, or symbolic use) or measuring impact (and at what level) or both. Continuing with the example about the EBP in provision of labor support, the question becomes “how do you wish to operationalize labor support?” What, precisely, do you mean by labor support? Does it include physical, emotional, and spiritual support? How would each of these be defined? Does support for a woman in labor include all support provided during the woman’s labor? Is it focused on support provided during certain stages? Is it restricted to health care providers’ provision of support? In other words, what exactly is the outcome to be measured?

Measurement of outcomes can be direct or indirect. Direct measures would be ones where the outcome can be directly observed or measured, such as would be the case by observation of the provision of labor support (either by an independent third party, her partner or care provider) or test scores about midwives’ or nurses’ knowledge about how to provide labor support. Indirect or surrogate measures are ones that only report on the outcome such as documentation in charts of the provision of labor support or its impact on the woman. Measures can also be subjective or objective. Subjective reports such as those based on self-reports by clinicians, women or their partners about the labor support provided often suffer from recall bias. Measures often considered more objective in nature (i.e., less susceptible to recall bias) would include observation and those derived from administrative databases of health records (e.g., the existence of a fetal monitoring strip in the health record indicating (EFM) electronic fetal monitoring). However, measures derived from documents are only as reliable as the quality and thoroughness of the original documentation. Indeed, clinicians may actually be engaged in EBP but not documenting it—for example postnatal records used in some English and Welsh maternity units may be decades old and not revised in line with recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance to inform the content of postnatal care (NICE 2006). Methods for collecting outcome measures typically include audit, surveys, interviews, and observation.

Selection of outcome measures should be guided by considerations such as scientific merit and pragmatic issues such as resource requirements to collect the data as well as the potential burden of administration. Issues related to scientific merit require assessment of the available measures as to their reliability, validity, and clinical sensitivity. Meaningful and sensitive measurement requires purposeful consideration of these factors in consultation with the stakeholders in the context of the project or study. The next sections consider issues around the measurement of knowledge use and its impact.

Measuring knowledge use

As has been suggested, knowledge use is a continuous and complex process that can manifest itself over several events (Rich 1991) rather than a single discrete event occurring at one point in time. Evaluating knowledge use can therefore be complex requiring a multidimensional, iterative, and systematic approach (Sudsawada 2007). Fortunately, there are some tools for assessing knowledge use. Dunn completed an inventory of tools available for conducting research on knowledge use (Dunn 1983). He identified 65 strategies to study knowledge use and categorized them into naturalistic observation, content analysis, and questionnaires and interviews (Dunn 1983). He also identified several scales for assessing knowledge use but found that most had unknown or unreported validity and reliability. Examples of questionnaires available to measure knowledge use include the Evaluation Utilization Scale (Johnson 1980) and Brett’s Nursing Practice Questionnaire (Brett 1987). This latter questionnaire focuses primarily on the stages of adoption as outlined by Rogers (Rogers 2003) including awareness, persuasion, decision, and implementation. Estabrooks developed a scale using four questions to measure overall research utilization, direct research utilization (instrumental use), indirect research utilization (conceptual use), and persuasive research utilization (symbolic use) (Estabrooks 1999). Skinner has developed a tool for measuring knowledge exchange outcomes that is undergoing pilot testing (Skinner 2007). This tool consists of two categories: reach (the extent to which best practices are known to potential users, i.e., conceptual use) and uptake (behavioral efforts to use best practices, i.e., instrumental use).

There are a numerous other measures of knowledge use that focus on the multiple decisions required for knowledge use and view the process as a continuum occurring over time. These measures include Halls levels of use scale (Hall et al. 1975) (non-use, orientation (initial formation), preparation (to use), mechanical use, routine, refinement, integration, and renewal), the Peltz and Horsley research utilization index (Peltz & Horsley 1981), the Larson information utilization scale (considered or rejected, nothing done, under consideration, steps toward implementation, partially implemented, implemented as presented, implemented, and adapted) (Larson 1982), and the Knott and Wildavsky stages of research utilization (Knott & Wildavsky 1980). Landry and colleagues have validated this latter scale which includes six stages: reception, cognition, discussion, reference, effort and influence, and implementation (Landry et al. 2001). Landry and colleagues also developed another similar scale to measure knowledge use by policy makers (Landry et al. 2003). Moersch has modified Hall’s levels to provide guidance for determining the extent of implementation using seven levels: non-use, awareness, exploration, infusion, integration, expansion, and refinement (Moersch 1995). Champion and Leach developed a knowledge utilization scale that assesses four sets of items: attitudes toward research, availability or access of research, use of research in practice, and support to use research (Champion & Leach 1989).

Most frequently, knowledge utilization tools measure instrumental knowledge use (Estabrooks et al. 2003). In systematic reviews synthesizing the results of studies of effectiveness of interventions to influence the uptake of practice guidelines (Grimshaw et al. 2004; Harrison et al. 2010), measures of instrumental knowledge use (i.e., guideline adherence) are included in upward of 89% of practice guideline implementation studies in medicine, nursing, and allied health professionals included in these reviews (Hakkennes & Green 2006; see Chapter 10).

These measures, however, often rely on self-report and are subject to recall bias. For example, an exploratory case study investigated call center nurses’ sustained use of a decision support protocol (Stacey et al. 2006b); participating nurses were surveyed about whether they used the decision support tool in practice. Eleven of 25 respondents stated that they had used the tool and 22 of 25 said they would use it in the future. The authors identified potential limitations to this study including recall bias and a short follow-up period (1 month) without repeated observation (Stacey et al. 2006b). In a more valid assessment of instrumental knowledge use, participants also underwent a quality assessment of their coaching skills during simulated calls (observation of the practitioner–patient encounter) (Stacey et al. 2006a). Assessing instrumental knowledge use can also be done by measuring adherence to recommendations or quality indicators using administrative databases or chart audits. Another way to measure instrumental knowledge use can involve observing service user–clinician encounters and addressing the extent to which the EBPs are used. Asking service users about their health care encounter, which has all the limitations of self-report, is another means of assessing EBP.

Conceptual knowledge use can be measured by tests of knowledge/understanding (e.g., the extent to which clinicians acquire the knowledge and skills taught during training sessions) which is why surveys of attitudes and intentions (e.g., measures of attitudes toward a specific practice, perceptions of self-efficacy performing the practice, or intentions to perform them) are common outcome measures in implementation studies or studies of EBP (Godin et al. 2008). For example, in a randomized controlled trial of an intervention to implement evidence-based patient decision support in a nurse call center, part of the intervention included nurses taking a 3-hour online tutorial (Stacey et al. 2006a). Incorporated into the tutorial was a knowledge test to determine whether the nurses had acquired the relevant knowledge and skills to be able to provide decision support. Around 50% of guideline implementation studies in nursing and allied health professions included measures of conceptual knowledge use compared with less than 20% in medicine (Hakkennes & Green 2006; see Chapter 10).

In addition to considering the type of knowledge use, we should also consider who we want to use the knowledge (i.e., the public or service users, health care professionals, managers/administrators, policy makers). Different target audiences may require different strategies for monitoring knowledge use. For example, when the target is policy makers, a decision to adopt or endorse a particular practice guideline for their jurisdiction enables instrumental use. Assessing the use of knowledge by policy makers may require strategies such as interviews and document analysis (Hanney et al. 2002). When assessing knowledge use by clinicians, we could consider measuring awareness of the existence of guideline recommendations, knowledge of the content of the recommendations and actual application of guideline recommendations.

When implementing EBP, it is also important to consider the degree of knowledge use that we are aiming for. This should be based on discussions with relevant stakeholders including consideration of what is acceptable and feasible and whether a ceiling effect may exist (Straus et al. 2009). If the level of knowledge use is found to be adequate, strategies for monitoring sustained knowledge use should be considered. If the level of knowledge use is less than expected or desired, it may be useful to reassess barriers to knowledge use. Target decision makers could be asked about their intention to use the knowledge. This exploration may uncover new barriers. In the case study of the use of decision support for a nurse call center, a survey of the nurses identified that use of the decision support tool might be facilitated through its integration in the call center database, incorporating decision support training for staff, and informing the public of this service.

Evaluating the impact of knowledge use

When considering the implementation of EBP, assessing level of knowledge use is important but the bottom line would always be important service user/patient or clinical, provider, and system outcomes. We should not lose sight of the fact that the ultimate goals of EBP are improved health status and quality of care.

Evaluation of impact should start with formulating the question of interest. We find using the PICO framework to be useful for this task (Straus et al. 2009). Using this framework, the “P” refers to the population of interest which could be the public, health care providers, or policy makers. The “I” refers to the implementation/KT intervention which was implemented and which might be compared to another group (“C”). The “O” refers to the outcome of interest which in this situation refers to health, provider or organizational outcomes.

The value of considering the impacts of research utilization in terms of patient, provider, and system or organization outcomes have been discussed elsewhere (Graham and Logan 2004; Logan and Graham 1998). In a systematic review of methods used to measure change in outcomes following an implementation or knowledge translation intervention, Hakkennes and Green (2006) grouped measures into three main categories which we have modified to focus on impact of knowledge use. They are as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree