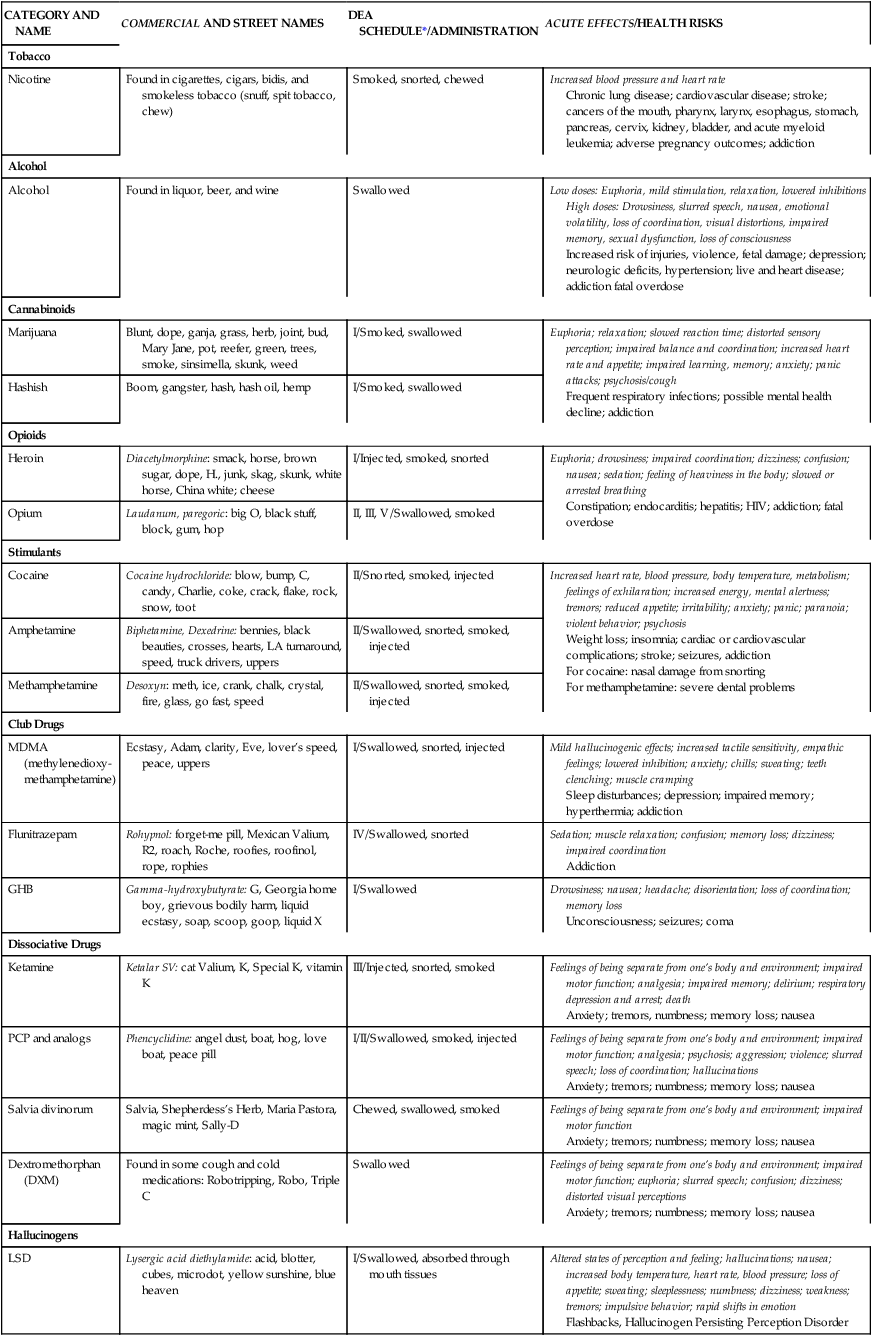

CHAPTER 22 Carolyn Baird and Margaret Jordan Halter 1. Describe the terms substance use, intoxication, tolerance, and withdrawal. 2. Define addiction as a chronic disease. 3. Describe the neurobiological process that occurs in the brain and neurotransmitters involved with substance use. 4. Identify potential co-occurring medical and psychological disorders. 5. Name the common classification of substances used. 6. Identify patterns of substance use 7. Apply the nursing process to caring for an individual who is using substances. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Substance disorders are not disorders of choice. They are complex diseases of the brain represented by craving, seeking, and using regardless of consequences (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2010a). Continuous substance use results in actual changes in the brain structure and function of an area of the brain referred to as the reward or pleasure center. This area of the brain within the limbic system is also the part of the brain that is affected by other mental health disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, or anxiety. More than half the individuals with a substance use disorder can be expected to have some other co-occurring mental health disorder and vice versa, leading researchers to suspect that there is an underlying genetic vulnerability (McCauley, 2009). It is important for all nurses regardless of their practice area to develop an understanding of the disease of addiction. Nursing curricula should include the content and practice the skills necessary for addiction screening, early detection, and referral to appropriate treatment. Without an accurate assessment for substance use and other mental health disorders, individuals will be unable to receive comprehensive treatment planning and quality care (Baird, 2011). A substance use disorder is a pathological use of a substance that leads to a disorder of use, intoxication, and, often, withdrawal if the substance is taken away. Substance use disorders encompass a broad range of products that human beings take into their bodies through various means (e.g., swallowing, inhaling, injecting). They range from fairly innocuous and innocent-seeming substances such as coffee to absolutely illegal, mind-altering drugs such as LSD. No matter the substance, use disorders share many commonalities, intoxication characteristics, and withdrawal attributes. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013) identifies the following substance-related and addictive disorders: While substances are generally associated as the source of addiction problems, behaviors, too, are gradually being recognized as addictive. Internet gaming, the use of social media, shopping, and sexual activity are also considered to be addictive. Behavioral addictions are also referred to as process addictions. The first behavioral addiction, gambling, was officially declared a disorder in 2013 (APA). Gambling and other compulsive actions activate dopamine and glutamate in the reward or pleasure neural pathways of the brain’s limbic system the same as substances do (Potenza, 2008). The activities are reinforced through the dopamine glutamate cycle and may become dysfunctional for the individual, resulting in many of the same problematic behaviors and functional issues as the ingested substances. See Table 22-1 for information on the commonly abused drugs. TABLE 22-1 *Drug Enforcement Agency Schedule I and II drugs have a high potential for abuse. They require greater storage security and have a quota on manufacturing, among other restrictions. Schedule I drugs are available for research only and have no approved medical use; Schedule II drugs are available only by prescription and require a form for ordering. Schedule III and IV drugs are available by prescription, may have five refills in six months, and may be ordered orally. Some Schedule V drugs are available over the counter. National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2011). Commonly abused drug chart. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/commonly-abused-drugs/commonly-abused-drugs-chart. When people are in the process of using a substance to excess they are said be experiencing intoxication. Intoxication may manifest itself in a variety of ways depending on the physiological response of the body to the substance that is being abused. Substances may be classified according to their mechanism of action as sedative hypnotics, stimulants, depressants, and hallucinogens. They are often casually referred to as uppers, downers, and all arounders (Palladini, 2011). Individuals who are using substances are considered to be “under the influence,” intoxicated, or high. Terminology may vary depending on the substance and the population who is using. Alcohol causes intoxication, but cocaine makes you high. Stimulants cause hyperreactivity, and depressants dampen responses. People with addictions experience tolerance to the effects of the substances. Tolerance is needing increasing amounts of a substance to receive the desired result or finding that using the same amount over time results in a much-diminished effect. Nursing students should know that some prescribed medications might have the same effect, such as some antianxiety medications, analgesics, and beta-blockers. Even antidepressants may result in tolerance (Fava & Offidani, 2011). This type of tolerance is not considered diagnostic when the individual is under medical supervision. Withdrawal is a set of physiological symptoms that begin to occur as the concentration of the chemical decreases in an individual’s bloodstream. It is specific to the substance ingested, and each substance has its own characteristic syndrome. The same substance, or one with a similar action, may be taken to avoid or relieve withdrawal symptoms. Although alcohol is the drug with the greatest potential for and most serious symptoms of withdrawal, the rising numbers of individuals abusing prescription drugs has increased the concern for assessing for withdrawal complications (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2011). Behavioral addictions such as gambling seldom have clearly identifiable intoxication or withdrawal symptoms, and tolerance is not an issue. Patterns of behavior and consequences are assessed to identify problematic behavior. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health is conducted annually on a randomly chosen segment of the population reflecting individuals 12 and older who reside in the United States. It is the primary source for national drug use statistics and trending. According to the 2010 survey, 22.6 million Americans used illicit substances, including the nonmedical use of prescription psychotherapeutics, in the month prior to the survey (Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2011). While slightly more than half (50.8% or 130.6 million) of the nation’s population admits to drinking alcohol, almost a quarter (23.1%) reports binge drinking (five drinks on one occasion on one day in the last month) and about 7% report heavy drinking (five drinks on one occasion on at least five days in the last month). In 2010, 3 million individuals used illicit drugs for the first time, and nearly 5 million individuals tried alcohol; most (82%) of them were younger than 21 years of age (SAMHSA, 2011). Overall, more than 22 million individuals, or nearly 9% of the population of the United States, are estimated to have substance use disorders. These numbers remained steady overall from 2002 to 2010. In 2010, marijuana had the highest percentage of misuse, followed by cocaine. Marijuana use has remained steady, with almost half of adolescents surveyed reporting that they have easy access to the drug. Cocaine use has been on the decline. It is the rise of prescription drug misuse that has prompted the greatest concern. Over half of individuals using prescription drugs nonmedically got them from a friend or relative for free, more than 10% percent paid a relative or friend for them, and another 9% percent stole them from a friend or relative (SAMHSA, 2011). More than 75% of these persons stated that their friend or relative had gotten them from just one doctor. Comorbidity refers to two or more disorders occurring in the same person at the same time with the potential for interaction and exacerbation of symptoms. It may be two or more psychiatric disorders, two or more medical disorders, or a combination of medical and psychiatric disorders (NIDA, 2011b). Although surveys have shown that individuals with substance use disorders have more than a 50% chance of having other mental health disorders of mood and vice versa, it cannot be said that one disorder caused the other, and it is difficult to determine which is primary. It is important that all disorders be identified and treated with a comprehensive approach. The high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity is supported by statistics collected since 1980 using multiple national population surveys. Individuals with mood and anxiety disorders, antisocial behaviors, or histories of conduct or oppositional disorders as adolescents are more than twice as likely to have a substance use disorder (NIDA, 2010b). Three common representations of comorbidity have been identified: 1. The physiological response to certain drugs of abuse presents a cluster of symptoms similar to the symptoms of other mental health disorders (e.g., psychosis, and schizophrenia). 2. Subclinical symptoms from one mental health disorder may result in medication of those symptoms with a psychoactive drug (social anxiety and alcohol or marijuana). 3. Psychiatric illnesses and substance use disorders have common risk factors. These shared risk factors are genetic vulnerabilities, underlying brain defects in common areas and pathways of the brain, and environmental factors, including exposure to stress or trauma during early developmental stages. Estimates suggest that 40% to 60% of an individual’s risk is in genetic vulnerabilities. For this reason, research on substance use and co-occurring disorders has been focusing on trying to identify any genes that may be implicated (NIDA, 2010b). Genes may act individually or in complex interactions of multiple genes to determine an individual’s level of susceptibility to risk-taking behavior, response to stress, or metabolism of substances. Research has also identified that the brain circuitry associated with the neurotransmitter dopamine is implicated in addictive disorders, depression, schizophrenia, and other mental health disorders. It has been proposed that deficits or dysfunction in this circuitry may predispose individuals to develop one or multiple psychiatric disorders. The human brain undergoes dramatic growth from age 5 to 20 and most particularly in adolescence (NIDA, 2010b). Any insult (stress or trauma) during this time may alter the brain circuitry and cause long-term changes in the abilities of decision making, learning and memory, reward, and affect and behavioral control. Early drug use or mental health disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or schizophrenia, could be risk factors for all co-occurring disorders but at this time are not considered fully predictive. More research is indicated to determine the role of genetic vulnerabilities and the influence of environmental and psychosocial factors (NIDA, 2010b). According to the 2001-2003 National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), 58% of all adults have some type of medical condition while 29% of these adults also have a comorbid psychiatric disorder. At the same time, 68% of adults with a psychiatric disorder have at least one medical disorder. These numbers suggest that 17% (34 million) of the adult population have psychiatric and medical comorbidities (Druss & Walker, 2011). The more common co-occurring medical conditions are hepatitis C, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, HIV, and pulmonary disorders (NIDA, 2010b). The high comorbidity appears to be the result of shared risk factors, high symptom burden, physiological response to licit and illicit drugs, and complications from the route of administration of substances (Druss & Walker, 2011). Addiction is a primary and chronic disease that is related to reward, memory, motivation, and circuitry (American Society for Addiction Medicine, 2011). It is characterized by an individual’s compulsive seeking of drugs and use despite the amazingly harmful consequences (NIDA, 2009). The parts of the brain most affected by drug use are the brain stem, the limbic system, and the frontal cortex. The reward pathways for motivation and memory are located in the limbic system and are influenced by neurobiological as well as psychological and sociocultural factors (Koob, 2009). Psychoactive substances and certain behaviors can hijack this reward pathway circuit, releasing as much as 10 times the amount of dopamine as usual. Over time, the release of dopamine becomes more important than the reward of pleasure, and the increased saliency of the addictive process cancels the inhibitory function of the frontal cortex, leading to craving (McCauley, 2009; Wright, 2011). The brain responds to this imbalance by resetting the pleasure threshold, producing transporter chemicals, and decreasing or down regulating the number of receptors attempting to reach homeostasis. This is the mechanism that is responsible for drug tolerance. Shared psychodynamics such as chronic stress and trauma have been identified in the histories of individuals with both substance use and mood disorders. Individuals who experienced abuse or neglect during childhood report more depression and suicidality. Chronic stressors such as poverty, the time and financial obligations of caring for children, and harmful relationships can lead to depression. Domestic violence, combat experience, and exposure to other forms of trauma may lead to posttraumatic stress disorder, major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and substance use disorders (Druss & Walker, 2011). Many times, there are multiple addictive behaviors that seem to support a shared vulnerability or antecedent. Many chronic stressors have their roots in socioeconomic factors. Poverty raises the risk of an unfavorable living environment, lack of parental supervision, poor educational resources, and impaired support systems (Druss & Walker, 2011). A cycle of negative environmental events often begins within disadvantaged neighborhoods, increasing stress and anxiety along with lacking or negative social ties, which contributes to depression. Coping mechanisms may include drugs and acting out behaviors leading to destructive consequences and interaction with the legal system. Screening is essential in order to intervene early and provide treatment for people with substance use disorders and for those at risk of developing these disorders. In one study, about 460,000 individuals were screened for substance use in select medical settings in six different states. A surprisingly high portion of patients screened—23%—was positive for a current or potential substance use problem (Madras et al., 2009). The Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) (SAMHSA, 2012) is a public health response to this problem. It consists of three major components: • Screening: A nurse or other health care professional in any health care setting assesses a patient for substance use problems using standardized screening tools. • Brief Intervention: A nurse or other health care professional discusses the risks of substance use behaviors with the patient and provides feedback and advice. • Referral to Treatment: A nurse or other health care professional suggests a referral for brief therapy or treatment for patients who screen positively. A variety of screening tools are available to assist health care practitioners in gaining important information on which to base plans of care. Simply asking about patterns of use, type of substance, and amounts used is helpful in establishing a baseline. No in-depth knowledge of addiction is necessary for this type of screening. Table 22-2 provides guidelines for assessing excessive amounts of alcohol use. Formalized alcohol screening is as simple as using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) developed for the World Health Organization (Babor et al., 2006) (Table 22-3). This tool can be administered by a clinician or through self-report. Scores of 8 or more in men and 7 or more in women indicate problematic alcohol use. TABLE 22-2 ALCOHOL AMOUNTS THAT INDICATE RISKY/HAZARDOUS DRINKING BASED ON POPULATION

Substance-related and addictive disorders

Clinical picture

CATEGORY AND NAME

COMMERCIAL AND STREET NAMES

DEA SCHEDULE*/ADMINISTRATION

ACUTE EFFECTS/HEALTH RISKS

Tobacco

Nicotine

Found in cigarettes, cigars, bidis, and smokeless tobacco (snuff, spit tobacco, chew)

Smoked, snorted, chewed

Increased blood pressure and heart rate

Chronic lung disease; cardiovascular disease; stroke; cancers of the mouth, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, cervix, kidney, bladder, and acute myeloid leukemia; adverse pregnancy outcomes; addiction

Alcohol

Alcohol

Found in liquor, beer, and wine

Swallowed

Low doses: Euphoria, mild stimulation, relaxation, lowered inhibitions

High doses: Drowsiness, slurred speech, nausea, emotional volatility, loss of coordination, visual distortions, impaired memory, sexual dysfunction, loss of consciousness

Increased risk of injuries, violence, fetal damage; depression; neurologic deficits, hypertension; live and heart disease; addiction fatal overdose

Cannabinoids

Marijuana

Blunt, dope, ganja, grass, herb, joint, bud, Mary Jane, pot, reefer, green, trees, smoke, sinsimella, skunk, weed

I/Smoked, swallowed

Euphoria; relaxation; slowed reaction time; distorted sensory perception; impaired balance and coordination; increased heart rate and appetite; impaired learning, memory; anxiety; panic attacks; psychosis/cough

Frequent respiratory infections; possible mental health decline; addiction

Hashish

Boom, gangster, hash, hash oil, hemp

I/Smoked, swallowed

Opioids

Heroin

Diacetylmorphine: smack, horse, brown sugar, dope, H., junk, skag, skunk, white horse, China white; cheese

I/Injected, smoked, snorted

Euphoria; drowsiness; impaired coordination; dizziness; confusion; nausea; sedation; feeling of heaviness in the body; slowed or arrested breathing

Constipation; endocarditis; hepatitis; HIV; addiction; fatal overdose

Opium

Laudanum, paregoric: big O, black stuff, block, gum, hop

II, III, V/Swallowed, smoked

Stimulants

Cocaine

Cocaine hydrochloride: blow, bump, C, candy, Charlie, coke, crack, flake, rock, snow, toot

II/Snorted, smoked, injected

Increased heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, metabolism; feelings of exhilaration; increased energy, mental alertness; tremors; reduced appetite; irritability; anxiety; panic; paranoia; violent behavior; psychosis

Weight loss; insomnia; cardiac or cardiovascular complications; stroke; seizures, addiction

For cocaine: nasal damage from snorting

For methamphetamine: severe dental problems

Amphetamine

Biphetamine, Dexedrine: bennies, black beauties, crosses, hearts, LA turnaround, speed, truck drivers, uppers

II/Swallowed, snorted, smoked, injected

Methamphetamine

Desoxyn: meth, ice, crank, chalk, crystal, fire, glass, go fast, speed

II/Swallowed, snorted, smoked, injected

Club Drugs

MDMA (methylenedioxy-methamphetamine)

Ecstasy, Adam, clarity, Eve, lover’s speed, peace, uppers

I/Swallowed, snorted, injected

Mild hallucinogenic effects; increased tactile sensitivity, empathic feelings; lowered inhibition; anxiety; chills; sweating; teeth clenching; muscle cramping

Sleep disturbances; depression; impaired memory; hyperthermia; addiction

Flunitrazepam

Rohypnol: forget-me pill, Mexican Valium, R2, roach, Roche, roofies, roofinol, rope, rophies

IV/Swallowed, snorted

Sedation; muscle relaxation; confusion; memory loss; dizziness; impaired coordination

Addiction

GHB

Gamma-hydroxybutyrate: G, Georgia home boy, grievous bodily harm, liquid ecstasy, soap, scoop, goop, liquid X

I/Swallowed

Drowsiness; nausea; headache; disorientation; loss of coordination; memory loss

Unconsciousness; seizures; coma

Dissociative Drugs

Ketamine

Ketalar SV: cat Valium, K, Special K, vitamin K

III/Injected, snorted, smoked

Feelings of being separate from one’s body and environment; impaired motor function; analgesia; impaired memory; delirium; respiratory depression and arrest; death

Anxiety; tremors, numbness; memory loss; nausea

PCP and analogs

Phencyclidine: angel dust, boat, hog, love boat, peace pill

I/II/Swallowed, smoked, injected

Feelings of being separate from one’s body and environment; impaired motor function; analgesia; psychosis; aggression; violence; slurred speech; loss of coordination; hallucinations

Anxiety; tremors; numbness; memory loss; nausea

Salvia divinorum

Salvia, Shepherdess’s Herb, Maria Pastora, magic mint, Sally-D

Chewed, swallowed, smoked

Feelings of being separate from one’s body and environment; impaired motor function

Anxiety; tremors; numbness; memory loss; nausea

Dextromethorphan (DXM)

Found in some cough and cold medications: Robotripping, Robo, Triple C

Swallowed

Feelings of being separate from one’s body and environment; impaired motor function; euphoria; slurred speech; confusion; dizziness; distorted visual perceptions

Anxiety; tremors; numbness; memory loss; nausea

Hallucinogens

LSD

Lysergic acid diethylamide: acid, blotter, cubes, microdot, yellow sunshine, blue heaven

I/Swallowed, absorbed through mouth tissues

Altered states of perception and feeling; hallucinations; nausea; increased body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure; loss of appetite; sweating; sleeplessness; numbness; dizziness; weakness; tremors; impulsive behavior; rapid shifts in emotion

Flashbacks, Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder

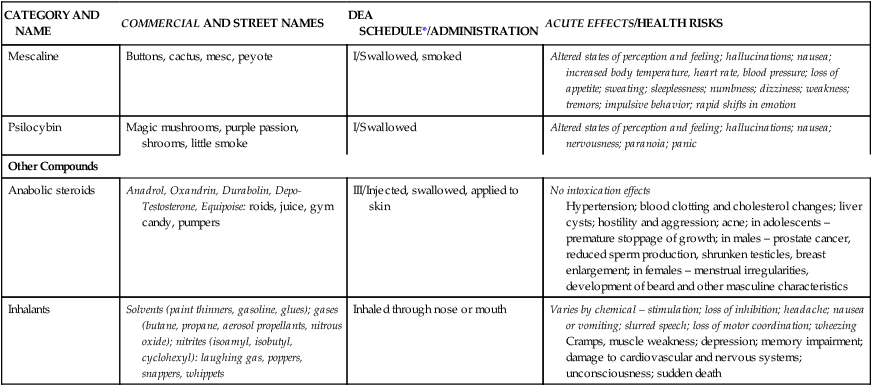

Mescaline

Buttons, cactus, mesc, peyote

I/Swallowed, smoked

Altered states of perception and feeling; hallucinations; nausea; increased body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure; loss of appetite; sweating; sleeplessness; numbness; dizziness; weakness; tremors; impulsive behavior; rapid shifts in emotion

Psilocybin

Magic mushrooms, purple passion, shrooms, little smoke

I/Swallowed

Altered states of perception and feeling; hallucinations; nausea; nervousness; paranoia; panic

Other Compounds

Anabolic steroids

Anadrol, Oxandrin, Durabolin, Depo-Testosterone, Equipoise: roids, juice, gym candy, pumpers

III/Injected, swallowed, applied to skin

No intoxication effects

Hypertension; blood clotting and cholesterol changes; liver cysts; hostility and aggression; acne; in adolescents – premature stoppage of growth; in males – prostate cancer, reduced sperm production, shrunken testicles, breast enlargement; in females – menstrual irregularities, development of beard and other masculine characteristics

Inhalants

Solvents (paint thinners, gasoline, glues); gases (butane, propane, aerosol propellants, nitrous oxide); nitrites (isoamyl, isobutyl, cyclohexyl): laughing gas, poppers, snappers, whippets

Inhaled through nose or mouth

Varies by chemical – stimulation; loss of inhibition; headache; nausea or vomiting; slurred speech; loss of motor coordination; wheezing

Cramps, muscle weakness; depression; memory impairment; damage to cardiovascular and nervous systems; unconsciousness; sudden death

Concepts that are central to substance use disorders

Epidemiology

Comorbidity

Psychiatric comorbidity

Medical comorbidity

Etiology

Neurobiological factors

Psychological factors

Sociocultural factors

Application of the nursing process

Screening

POPULATION

MEN

WOMEN

PREGNANT

ADOLESCENT

ELDERLY

Day/occasion

4

3

0

0

3

Week

14

7

0

0

7 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree