Stress and Coping

Objectives

• Describe the three stages of the general adaptation syndrome.

• Describe characteristics of posttraumatic stress disorder.

• Discuss the integration of stress theory with nursing theories.

• Describe stress management techniques beneficial for coping with stress.

• Discuss the process of crisis intervention.

• Develop a care plan for patients who are experiencing stress.

Key Terms

Adventitious crises, p. 734

Alarm reaction, p. 732

Allostatic load, p. 732

Appraisal, p. 731

Burnout, p. 741

Coping, p. 732

Crisis, p. 731

Crisis intervention, p. 742

Developmental crises, p. 734

Ego-defense mechanisms, p. 733

Exhaustion stage, p. 732

Fight-or-flight response, p. 731

Flashback, p. 734

General adaptation syndrome (GAS), p. 732

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), p. 733

Primary appraisal, p. 732

Resistance stage, p. 732

Secondary appraisal, p. 732

Situational crises, p. 734

Stress, p. 731

Stressors, p. 731

Trauma, p. 731

![]()

Health care professionals need to know about stress so they are able to recognize it in patients and families and intervene effectively. Caregiver stress frequently affects family members of patients and must be considered in patient care. Equally important, health care professionals also experience stressful events that occur in the course of clinical practice and in their own lives. Nurses need to recognize the signs and symptoms of stress and understand stress management techniques to aid personal coping and design stress management interventions for their patients and families.

People use the term stress in many ways. It is an experience to which a person is exposed through a stimulus or stressor. Stressors are tension-producing stimuli operating within or on any system (Neuman and Fawcett, 2011). It is also the appraisal, or perception, of a stressor. Appraisal is how people interpret the impact of the stressor on themselves or on what is happening and what they are able to do about it (Lazarus, 2007). Finally stress is a physical, emotional, or psychological demand that often leads to growth or overwhelms a person and leads to illness (Varcarolis and Halter, 2010). Stress refers to the consequences of the stressor and the person’s appraisal of it.

People experience stress as a consequence of daily life events and experiences. It stimulates thinking processes and helps people stay alert to their environment. It results in personal growth and facilitates development. How people react to stress depends on how they view and evaluate the impact of the stressor, its effect on their situation and support at the time of the stress, and their usual coping mechanisms. When stress overwhelms existing coping mechanisms, patients lose emotional balance, and a crisis results. If symptoms of stress persist beyond the duration of the stressor, a person has experienced a trauma.

Scientific Knowledge Base

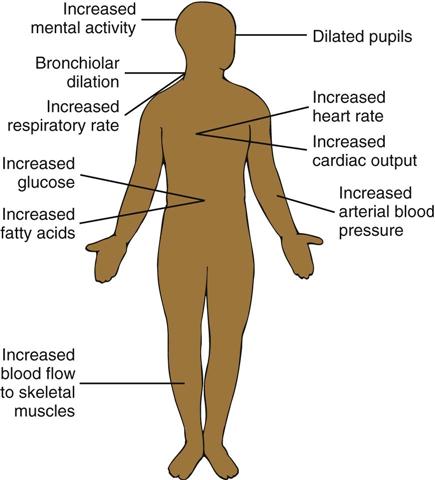

The fight-or-flight response to stress, which is arousal of the sympathetic nervous system, prepares a person for action (Fig. 37-1). Neurophysiological responses to stress function through negative feedback. The process of negative feedback senses an abnormal state such as lowered body temperature and makes an adaptive response such as initiating shivering to generate body heat. Three structures, the medulla oblongata, the reticular formation, and the pituitary gland, control the response of the body to a stressor.

Medulla Oblongata

The medulla oblongata, located in the lower portion of the brainstem, controls heart rate, blood pressure, and respirations. Impulses traveling to and from the medulla oblongata increase or decrease these vital functions. For example, sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous system impulses traveling from the medulla oblongata to the heart control regulation of the heartbeat. The heart rate increases in response to impulses from sympathetic fibers and decreases with impulses from parasympathetic fibers.

Reticular Formation

The reticular formation, a small cluster of neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord, continuously monitors the physiological status of the body through connections with sensory and motor tracts. For example, certain cells within the reticular formation cause a sleeping person to regain consciousness or increase the level of consciousness when a need arises.

Pituitary Gland

The pituitary gland is a small gland immediately beneath the hypothalamus. It produces hormones necessary for adaptation to stress such as adrenocorticotropic hormone, which in turn produces cortisol. In addition, the pituitary gland regulates the secretion of thyroid, gonadal, and parathyroid hormones. A feedback mechanism continuously monitors hormone levels in the blood and regulates hormone secretion. When hormone levels drop, the pituitary gland receives a message to increase hormone secretion. When they rise, it decreases hormone production.

General Adaptation Syndrome

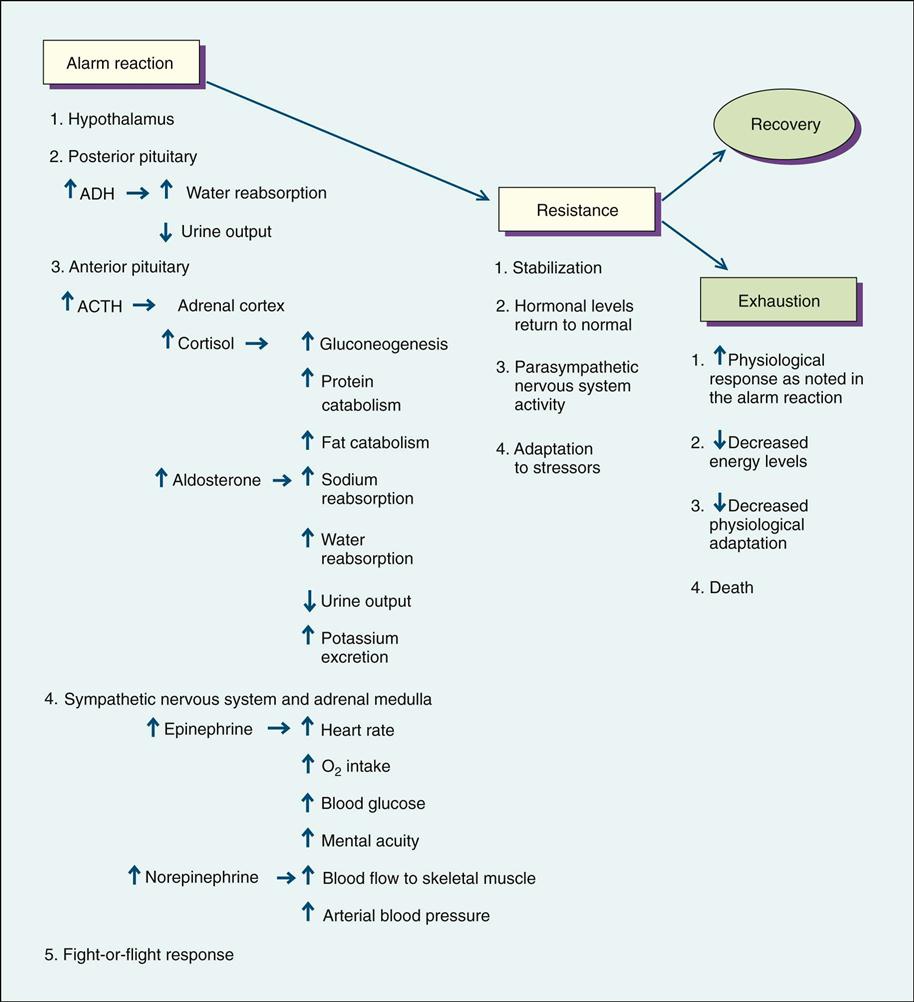

The general adaptation syndrome (GAS), a three-stage reaction to stress, describes how the body responds to stressors through the alarm reaction, the resistance stage, and the exhaustion stage. The GAS is triggered either directly by a physical event or indirectly by a psychological event. It involves several body systems, especially the autonomic nervous and endocrine systems, and responds immediately to stress (Fig. 37-2). When the body encounters a physical demand such as an injury, the pituitary gland initiates the GAS.

During the alarm reaction rising hormone levels result in increased blood volume, blood glucose levels, epinephrine and norepinephrine amounts, heart rate, blood flow to muscles, oxygen intake, and mental alertness. In addition, the pupils of the eyes dilate to produce a greater visual field. If the stressor poses an extreme threat to life or remains for a long time, the person progresses to the second stage, resistance.

During the resistance stage the body stabilizes and responds in a manner opposite to that of the alarm reaction. Hormone levels, heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac output return to normal; and the body repairs any damage that has occurred. However, if the stress response is chronically activated, a state of allostasis occurs. This chronic arousal with the presence of powerful hormones causes excessive wear and tear on the person and is called allostatic load. An increased allostatic load leads to chronic illness (Diamond, 2009/2010). A persistent allopathic load can cause long-term physiological problems such as chronic hypertension, depression, sleep deprivation, chronic fatigue syndrome, and autoimmune disorders (McEwen, 2005).

The exhaustion stage occurs when the body is no longer able to resist the effects of the stressor and has depleted the energy necessary to maintain adaptation. The physiological response has intensified; but with a compromised energy level, the person’s adaptation to the stressor diminishes.

Reaction to Psychological Stress.

The GAS is activated indirectly for psychological threats, which are different for each person and produce differing reactions. The intensity and duration of the psychological threat and the number of other stressors that occur at the same time affect the person’s response to the threat. In addition, whether or not the person anticipated the stressor influences its effect. It is often more difficult to cope with an unexpected stressor. Personal characteristics that influence the response to a stressor include the level of personal control, presence of a social support system, and feelings of competence.

A person experiences stress only if the event or circumstance is personally significant. Evaluating an event for its personal meaning is primary appraisal. Appraisal of an event or circumstance is an ongoing perceptual process. If primary appraisal results in the person identifying the event or circumstance as a harm, loss, threat, or challenge, the person experiences stress. If stress is present, secondary appraisal focuses on possible coping strategies. Balancing factors contribute to restoring equilibrium. According to crisis theory, feedback cues lead to reappraisals of the original perception. Therefore coping behaviors constantly change as individuals perceive new information.

Coping is the person’s effort to manage psychological stress. Effectiveness of coping strategies depends on the individual’s needs. A person’s age and cultural background influence these needs. For this reason no single coping strategy works for everyone or for every stressor. The same person may cope differently from one time to another. In stressful situations most people use a combination of problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies. In other words, when under stress a person obtains information, takes action to change the situation, and regulates emotions tied to the stress. In some cases people avoid thinking about the situation or change the way they think about it without changing the actual situation itself. The type of stress, people’s goals, their beliefs about themselves and the world, and personal resources determine how people cope with stress. Resources include intelligence, money, social skills, supportive family and friends, physical attractiveness, health and energy, and ways of thinking such as optimism (Lazarus, 2007).

Coping mechanisms include psychological adaptive behaviors. Such behaviors are often task oriented, involving the use of direct problem-solving techniques to cope with threats. Ego-defense mechanisms regulate emotional distress and thus give a person protection from anxiety and stress. Ego-defense mechanisms help a person cope with stress indirectly and offer psychological protection from a stressful event. Everyone uses them unconsciously to protect against feelings of worthlessness and anxiety. Occasionally a defense mechanism becomes distorted and no longer helps the person adapt to a stressor. However, people generally find them very helpful in coping and use them spontaneously (Box 37-1). Frequently short-term stressors activate ego-defense mechanisms. These usually do not result in psychiatric disorders.

Types of Stress

Stress includes work, family, chronic, and acute stress; daily hassles; trauma; and crisis. One person looks at a stimulus and sees it as a challenge, leading to mastery and growth. Another sees the same stimulus as a threat, leading to stagnation and loss. The individual with family responsibilities and a full-time job outside the home can experience chronic stress. It occurs in stable conditions and from stressful roles. Living with a long-term illness produces chronic stress. Conversely, time-limited events that threaten a person for a relatively brief period provoke acute stress. Recurrent daily hassles such as commuting to work, maintaining a house, dealing with difficult people, and managing money further complicate chronic or acute stress.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) begins when a person experiences, witnesses, or is confronted with a traumatic event and responds with intense fear or helplessness. Some examples of traumatic events that lead to PTSD include motor vehicle crashes, natural disasters, violent personal assault, and military combat. Anxiety associated with PTSD is sometimes manifested by nightmares and emotional detachment. Some people with PTSD experience flashbacks, or recurrent and intrusive recollections of the event. Responses may also include self-destructive behaviors such as suicide attempts and substance abuse.

A crisis implies that a person is facing a turning point in life. This means that previous ways of coping are not effective and the person must change. There are three types of crises: (a) maturational or developmental crises, (b) situational crises, and (c) disasters or adventitious crises (Varcarolis and Halter, 2010). A new developmental stage such as marriage, birth of a child, or retirement requires new coping styles. Developmental crises occur as a person moves through the stages of life. External sources such as a job change, a motor vehicle crash, a death, or severe illness provoke situational crises. A major natural disaster, man-made disaster, or crime of violence often creates an adventitious crisis.

Patient-centered care provides an important context for crisis intervention. The view of the person experiencing a crisis is the frame of reference for the crisis. The vital questions for a person in crisis are, “What does this mean to you; how is it going to affect your life?” What causes extreme stress for one person is not always stressful to another. The perception of the event, situational supports, and coping mechanisms all influence return of equilibrium or homeostasis. A person either advances or regresses as a result of a crisis, depending on how he or she manages the crisis (Lazarus, 2007).

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nurses have proposed theories related to stress and coping. Because stress plays a central role in vulnerability to disease, symptoms of stress often require nursing intervention.

Nursing Theory and the Role of Stress

The Neuman Systems Model is based on the concepts of stress and reaction to it. Nurses are responsible for developing interventions to prevent or reduce stressors on the patient or make them more bearable him or her (Neuman and Fawcett, 2011). This model views the person, family, or community as constantly changing in response to the environment and stressors and helps explain individual, family, and community responses to stressors. All systems experience multiple stressors, each of which potentially disturbs the person’s, family’s, or community’s balance. Examples of stress include intrapersonal stressors such as an illness or injury, interpersonal stressors such as an argument or misunderstanding between two people, or extrapersonal stressors such as financial concerns. Every person develops a set of responses to stress that constitute the “normal line of defense” (Neuman and Fawcett, 2011). This line of defense helps to maintain health and wellness. However, when physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, or spiritual resources are unable to buffer stress, the normal line of defense is broken, and disease often results.

The Neuman Systems Model emphasizes the importance of accuracy in assessment and interventions that promote optimal wellness using primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies (Neuman and Fawcett, 2011). According to Neuman’s theory, the goal of primary prevention is to promote patient wellness by stress prevention and reduction of risk factors. Secondary prevention occurs after symptoms appear. The nurse determines the meaning of the illness and stress to the patient and the patient’s needs and resources for meeting them. Tertiary prevention begins when the patient’s system becomes more stable and recovers. At the tertiary level of prevention the nurse supports rehabilitation processes involved in healing and moving the patient back to wellness and the primary level of disease prevention.

Factors Influencing Stress and Coping

Potential stressors and coping mechanisms vary across the life span. Adolescence, adulthood, and old age bring different stressors. The appraisal of stressors, the amount and type of social support, and coping strategies all balance when assessing stress and depend on previous life experiences. Furthermore, situational and social stressors place people who are vulnerable at higher risk for prolonged stress.

Situational Factors.

Situational stress arises from personal or family job changes or relocation. Stressful job changes include promotions, transfers, downsizing, restructuring, changes in supervisors, and additional responsibilities. Adjusting to chronic illness leads to situational stress. Common diseases such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, depression, asthma, and coronary artery disease provoke stress. Uncertainty associated with treatment and illness triggers stress in patients of all ages. Paying for treatment and limited access to providers also create stress. Although being a family caregiver for someone with a chronic illness such as Alzheimer’s disease is associated with stress, the actions of competent health care providers often minimize the stress for caregivers (Box 37-2).

Maturational Factors.

Stressors vary with life stage. Children identify stressors related to their physical appearance, their families, their friends, and school. Preadolescents experience stress related to self-esteem issues, changing family structure as a result of divorce or death of a parent, or hospitalizations. As adolescents search for their identity with peer groups and separate from their families, they experience stress. In addition, they face stressful questions about using mind-altering substances, sex, jobs, school, and career choices. Stress for adults centers around major changes in life circumstances. These include the many milestones of beginning a family and a career, losing parents, seeing children leave home, and accepting physical aging. In old age stressors include the loss of autonomy and mastery resulting from general frailty or health problems that limit stamina, strength, and cognition (Box 37-3).

Sociocultural Factors.

Environmental and social stressors often lead to developmental problems. Potential stressors that affect any age-group but are especially stressful for young people include prolonged poverty and physical handicap. Children become vulnerable when they lose parents and caregivers through divorce, imprisonment, or death or when parents have mental illness or substance abuse disorders. Living under conditions of continuing violence, disintegrated neighborhoods, or homelessness affects people of any age, especially young people (Pender et al., 2011). A person’s culture also influences stress and coping (Box 37-4).