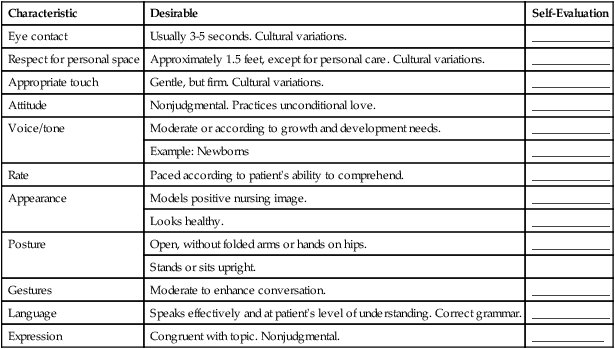

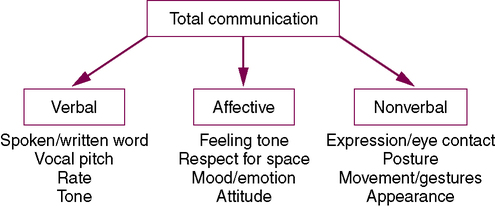

On completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. Explain the sender-receiver process in: 2. Discuss how nonverbal and affective communication can support or cancel the meaning of verbal communication. 3. Provide an example of how you use communication strategies in nursing. 4. Give an example of blocking therapeutic communication. 5. List two common differences in male/female communication that have biologic roots. 6. Give an example of a cultural communication difference in the area in which you live. 7. List two common factors related to role change for a hospitalized patient that can create distress. 8. Identify a communication difference for patients in two separate age groups. 9. Explain how common characteristics apply to straightforward communication with all people. 10. Identify the four steps of SBAR and give an example of how it can be used for nurse–physician communication. 11. Discuss ways to resolve conflict between you and another staff member. The three types of communication are verbal (spoken or written word), nonverbal (body language), and affective (feeling tone). They may or may not all occur at the same time. When they do occur together, all three must mirror one another (be congruent) for the communication to be honest (Figure 13-1). • Restating refers to repeating in a slightly different way what the patient has said—for example: Patient: “My chest hurts. I can’t sleep at night.” Nurse: “You’ve been unable to sleep at night because of chest pain.” • Clarifying is asking a closed-ended question in response to a patient’s statement to be sure you understand—for example: • Reflecting is putting into words the information you are receiving from the patient at an affective communication level—for example: Patient: “I’m sick of seeing doctors and not getting answers.” Nurse: “You are upset with the lack of answers to your health problems.” • Paraphrasing refers to expressing in your own words what you think the patient means—for example: Patient: “I don’t think I’m being told the truth about my condition.” Nurse: “You think you may be more ill than what the doctor is telling you.” • Minimal encouraging involves using sounds, words, or short phrases to encourage the patient to continue—for example: • Remaining silent involves using pauses effectively. The normal tendency is to fill silence with chatter or your speculation. This may cause the patient to “turn off” or change the story. Maintaining disciplined attention and focus during silence lets patients tell the story in their own way. Avoid making interruptions and doing busywork while the patient is speaking. • Summarizing means briefly stating the main data you have gathered—for example: • Validating provides the patient with an opportunity to correct information, if necessary, at the time of summary—for example:

Straightforward Communication

Instructors, Coworkers, and Patients

Types of Communication

Communication Strategies

Active listening behaviors

Straightforward Communication: Instructors, Coworkers, and Patients

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access