On completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. Identify the year and place the first school of practical nursing was founded. 2. Name the school’s most famous pupil. 3. Discuss the contributions of this most famous nurse. 4. Name the year in which licensing for practical nursing first began. 5. Present the rationale for your personal stand on entry into nursing practice. 6. Name one contribution of war nurses to overall nursing: Nursing has experienced many changes throughout its history (Table 7-1), and the changes continue. Two major changes that have occurred in practical nursing are a gradual increase in the required formal knowledge base and a requirement for licensing to practice practical nursing. Unlike the historically untrained or poorly trained practical nurse, who had unlimited and unsupervised freedom to practice, the present practical nurse is now often a hybrid. Today’s practical/vocational nursing student (SPN/SVN) is being taught basic skills during the nursing program. After licensing, the LPN/LVN is permitted to perform complex nursing skills as assigned by the registered nurse (RN) and allowed by their state’s nurse practice act. Assigning is allowed as long as the LPN/LVN feels confident performing the skill or the following requirements are met: Table 7-1 Being appointed to the task organizing and supervising nurses during the Crimean War gave Nightingale an unexpected opportunity for achievement. She left for Crimea, taking with her 38 self-proclaimed nurses of limited experience, 24 of whom were nuns. On arrival, they found overcrowded, filthy hospitals with no beds, no furniture, no eating utensils, no medical supplies, no blankets, no soap, no linens, and no lamps. Wounded soldiers lay on the filthy floor in their battle uniforms (Figure 7-1). Soldiers were more likely to die from infected wounds than the wound itself. Nightingale took charge. Using the supplies she brought, and raising funds, she purchased supplies that doctors could not obtain for the army. Nightingale hired people to clean up the “hospitals” and established laundries to wash linens and uniforms and prepare nutritious meals. She expected a great deal of herself and those who worked with her. It was not an easy task. A major prejudice that had to be overcome was that of medical officers, who considered the nurses intruders. The hours were long and difficult for Nightingale and her nurses. An additional concern was that sometimes nurses became more involved in converting patients to their particular faith than in giving general care. Nightingale hired tutors to teach convalescing soldiers how to read and write. Many soldiers had family following them, and recreation rooms were set up for their use. She believed that the best nurses were those who had good character, who experienced a sense of calling, and who were well trained to meet the physical needs of patients. The barracks, a 4-mile labyrinth of cots meant for 1700 patients, packed in 3000 to 4000 patients. She did not want her nurses on the wards after dark and could often be seen after hours making additional rounds with her lamp to check on patients. The soldiers fondly referred to her as “Birdie.” These extra efforts earned her the title “the Lady with the Lamp” as immortalized in Longfellow’s poem “Santa Filomena” (Box 7-1). Casualties were high on both sides during the Civil War. Many soldiers died right on the field, and others died because of a poorly trained medical corps. Southern women offered their services as volunteers, but most of the nursing was done by infantrymen assigned to do a task they did not want to do. It was many months before the Confederate government recognized southern women for their contributions (Figure 7-2).

How Practical/Vocational Nursing Evolved

1836 to the Present

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Hill/success

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Hill/success

Modern practical nurses

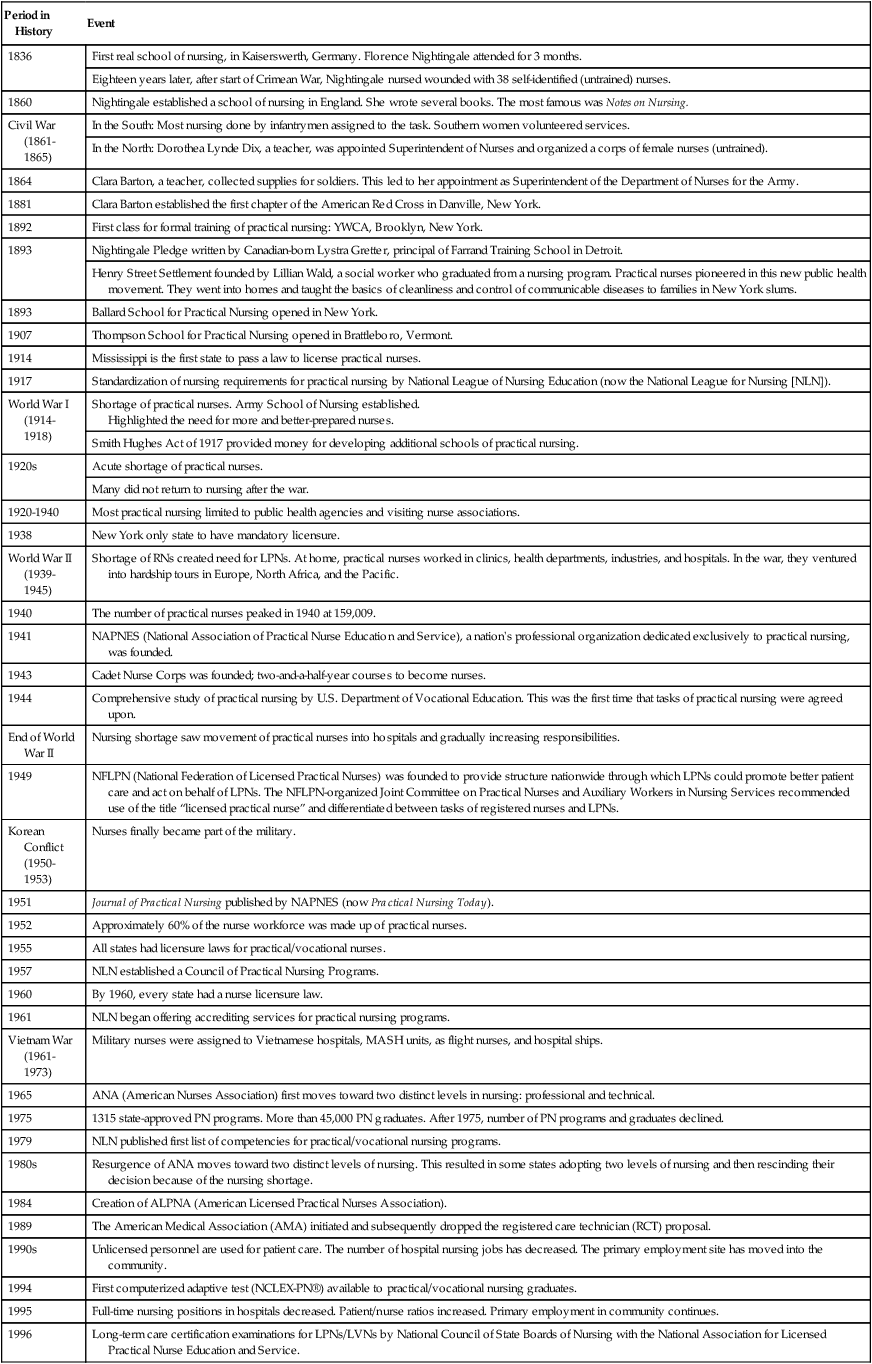

Period in History

Event

1836

First real school of nursing, in Kaiserswerth, Germany. Florence Nightingale attended for 3 months.

Eighteen years later, after start of Crimean War, Nightingale nursed wounded with 38 self-identified (untrained) nurses.

1860

Nightingale established a school of nursing in England. She wrote several books. The most famous was Notes on Nursing.

Civil War (1861-1865)

In the South: Most nursing done by infantrymen assigned to the task. Southern women volunteered services.

In the North: Dorothea Lynde Dix, a teacher, was appointed Superintendent of Nurses and organized a corps of female nurses (untrained).

1864

Clara Barton, a teacher, collected supplies for soldiers. This led to her appointment as Superintendent of the Department of Nurses for the Army.

1881

Clara Barton established the first chapter of the American Red Cross in Danville, New York.

1892

First class for formal training of practical nursing: YWCA, Brooklyn, New York.

1893

Nightingale Pledge written by Canadian-born Lystra Gretter, principal of Farrand Training School in Detroit.

Henry Street Settlement founded by Lillian Wald, a social worker who graduated from a nursing program. Practical nurses pioneered in this new public health movement. They went into homes and taught the basics of cleanliness and control of communicable diseases to families in New York slums.

1893

Ballard School for Practical Nursing opened in New York.

1907

Thompson School for Practical Nursing opened in Brattleboro, Vermont.

1914

Mississippi is the first state to pass a law to license practical nurses.

1917

Standardization of nursing requirements for practical nursing by National League of Nursing Education (now the National League for Nursing [NLN]).

World War I

(1914-1918)

Shortage of practical nurses. Army School of Nursing established.

Highlighted the need for more and better-prepared nurses.

Smith Hughes Act of 1917 provided money for developing additional schools of practical nursing.

1920s

Acute shortage of practical nurses.

Many did not return to nursing after the war.

1920-1940

Most practical nursing limited to public health agencies and visiting nurse associations.

1938

New York only state to have mandatory licensure.

World War II

(1939-1945)

Shortage of RNs created need for LPNs. At home, practical nurses worked in clinics, health departments, industries, and hospitals. In the war, they ventured into hardship tours in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific.

1940

The number of practical nurses peaked in 1940 at 159,009.

1941

NAPNES (National Association of Practical Nurse Education and Service), a nation’s professional organization dedicated exclusively to practical nursing, was founded.

1943

Cadet Nurse Corps was founded; two-and-a-half-year courses to become nurses.

1944

Comprehensive study of practical nursing by U.S. Department of Vocational Education. This was the first time that tasks of practical nursing were agreed upon.

End of World War II

Nursing shortage saw movement of practical nurses into hospitals and gradually increasing responsibilities.

1949

NFLPN (National Federation of Licensed Practical Nurses) was founded to provide structure nationwide through which LPNs could promote better patient care and act on behalf of LPNs. The NFLPN-organized Joint Committee on Practical Nurses and Auxiliary Workers in Nursing Services recommended use of the title “licensed practical nurse” and differentiated between tasks of registered nurses and LPNs.

Korean Conflict

(1950-1953)

Nurses finally became part of the military.

1951

Journal of Practical Nursing published by NAPNES (now Practical Nursing Today).

1952

Approximately 60% of the nurse workforce was made up of practical nurses.

1955

All states had licensure laws for practical/vocational nurses.

1957

NLN established a Council of Practical Nursing Programs.

1960

By 1960, every state had a nurse licensure law.

1961

NLN began offering accrediting services for practical nursing programs.

Vietnam War

(1961-1973)

Military nurses were assigned to Vietnamese hospitals, MASH units, as flight nurses, and hospital ships.

1965

ANA (American Nurses Association) first moves toward two distinct levels in nursing: professional and technical.

1975

1315 state-approved PN programs. More than 45,000 PN graduates. After 1975, number of PN programs and graduates declined.

1979

NLN published first list of competencies for practical/vocational nursing programs.

1980s

Resurgence of ANA moves toward two distinct levels of nursing. This resulted in some states adopting two levels of nursing and then rescinding their decision because of the nursing shortage.

1984

Creation of ALPNA (American Licensed Practical Nurses Association).

1989

The American Medical Association (AMA) initiated and subsequently dropped the registered care technician (RCT) proposal.

1990s

Unlicensed personnel are used for patient care. The number of hospital nursing jobs has decreased. The primary employment site has moved into the community.

1994

First computerized adaptive test (NCLEX-PN®) available to practical/vocational nursing graduates.

1995

Full-time nursing positions in hospitals decreased. Patient/nurse ratios increased. Primary employment in community continues.

1996

Long-term care certification examinations for LPNs/LVNs by National Council of State Boards of Nursing with the National Association for Licensed Practical Nurse Education and Service.

2000

Increased demand for LPNs/LVNs in nursing homes and extended care; demand down in hospitals.

2001—Afghanistan war

Military nurses help set up surgical teams, MASH units, air evacuation, combat support units in Afghan and Iraqi hospitals.

2003—Iraq war

2007

Nursing programs are turning students away because of the shortage of instructors.

Florence nightingale (1820–1910)

Crimean war 1853—1865

Early training schools in america

Civil war (1861—1865)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

How Practical/Vocational Nursing Evolved: 1836 to the Present

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access