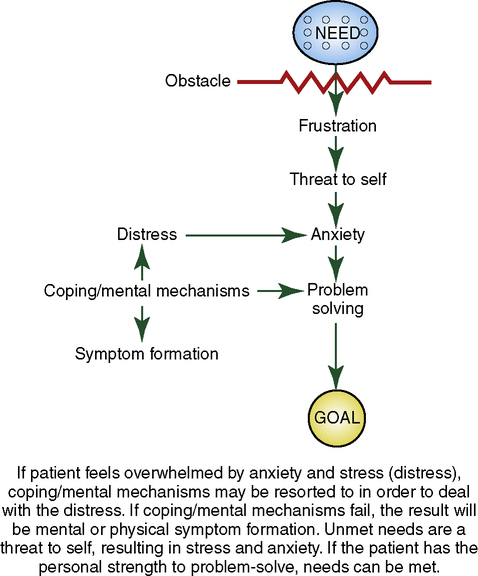

On completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. Explain why assertiveness is a nursing responsibility. 2. Differentiate among assertive, aggressive, and nonassertive (passive) behavior. 3. Describe three negative interactions in which nurses can get involved. 4. Maintain a daily journal that reflects your personal interactions and responses. 5. Explain the use of the problem-solving process to make a personal plan for change toward assertive behavior. 6. Discuss positive manipulation as a cultural choice. 7. Discuss codependency as an attempt to find relief from unresolved feelings. 8. Differentiate between lateral violence, bullying, and vertical violence in nursing. 9. Discuss dealing with sexual harassment in nursing. 10. Explain why insidious aggression is difficult to deal with. 11. List two to three behavioral changes in an individual that may clue you in to possible employee violence. 12. Identify steps you can personally take to make your workplace a happier and safer environment. • Tells another nurse how “stupid” the doctor is for ordering a certain type of treatment (indirect, nonassertive behavior). • Limits contact with a patient he or she is uncomfortable with to required care only (indirect nonassertive behavior). • Routinely tells patients who ask questions about their illness, test, medications, or treatment to “ask the doctor” or “ask the RN.” Although this answer is advisable some of the time, it certainly is a form of brush-off. Part of nursing responsibility is to seek answers for the patient (takes the easy way out). • Experiences inability to continue with a necessary, uncomfortable treatment ordered for the patient (interprets patient’s expression of discomfort personally: “The patient will not like me if I do this”). • May assume, without checking, that the patient wants to skip daily personal care when a visitor drops in (avoids conflict). • Experiences a feeling of being “devastated” when a patient, doctor, nurse, or other staff person criticizes his or her work (interprets criticism of work as criticism of self). • Responds to patient’s questions about own personal life and that of other staff (afraid of not being liked). • Patient asks nurse to pick up some personal items on the way home. Nurse frowns but agrees to do so (communicates real message nonverbally). • Becomes angry with the team leader and drops hints to others about own feelings (communicates real message indirectly). • When asked by another nurse to assist with the care of assigned patients, responds by saying, “Well, uh, I guess I could,” although already too busy (hesitate, repressing own wishes). • Needs help with assignment but says nothing (refrains from expressing own needs). • After making an error, overexplains and overapologizes (is unaware of the right to make a mistake; should take responsibility for it, learn from the error, and go on). • Plans on finding a new job because of fear of approaching supervisor to tell own side of what has happened (avoids conflict). • When “chewed out” by the doctor in front of a patient, gets angry but says nothing (refrains from expressing own opinion—internalizes anger). • You have asked to go to a workshop, and the supervisor says, “Why should you go? Everyone else has worked here longer than you have” (attempts to make you feel guilty for making a request). • Another nurse points out your error in front of other staff and adds, “Where did you say you graduated from?” (attempts to humiliate as a way of controlling). • A peer approaches you with a problem. You don’t want to listen and say, “If it isn’t one thing, it’s another for you. Why don’t you get your act together?” (disregards others’ feelings). • A new rule is instituted without requesting input from or informing those it will involve. You protest but are told, “That’s tough; this is the way it’s going to be from now on” (disregards others’ feelings and rights). • The patient has had his call light on frequently throughout the morning. You walk in and say, “I have had it. You have had your light on continuously for nothing all morning. Do not put your light on again unless you are dying, or I will take it away” (hostile overreaction out of proportion to the issue at hand). • You attempted to express your feelings to a peer about his or her behavior toward you. Today the peer greets you with an icy stare when you say hello (hostile overreaction). • The patient tells you, “I thought this was a pretty good hospital, but none of you seem to know what you are doing” (sarcastic, hostile). • You push yourself in front of others in the cafeteria line (rudeness). • You ask the nurse manager a question. Instead of answering, he just stares at you with lips curled slightly upward (attempt to make you uncomfortable, a put-down). • The doctor orders a medication or treatment that seems inappropriate. You request to talk to the doctor privately and ask about expected outcomes. You present any new information you have that may potentially affect the decision to continue with the order (direct statement of information). • The patient has been giving you a bad time. Pulling up a chair and sitting down, you say, “Mr. Smith, I would be interested in knowing what is going on with you. I have noticed that whatever I do, you are critical of my work.” Then you listen attentively and with understanding (comprehension) and respond nondefensively (direct statement of feelings; does not interpret patient’s criticism as a personal attack). • When the patient requests information you are unfamiliar with regarding the illness and treatment, you say, “I do not know, but I will find out for you.” You follow through by checking with appropriate staff. You determine who is to inform the patient (respects the patient’s right to know). • The doctor has ordered the patient to walk for 10 minutes out of each hour. The patient complains that it hurts and asks to not be required to walk. You respond by saying, “I know it is uncomfortable, but I will walk along beside you. We can stop briefly any time you like. I will also teach you how to do a brief relaxation technique [see Chapter 6] that you can use while you are walking.” If pain medication is available, you will also make sure that this is given before walking and in enough time for the medication to take effect (respects patient’s feelings but supports the need to carry out doctor’s orders). • Unexpected visitors arrive when it is time for you to help the patient with personal care. You ask the patient directly if care should be done now or postponed briefly. You state the time that you will be available to assist with care (respects the patient’s right to choose, as long as it does not compromise the care). • You have just been criticized for your work. You respond by saying, “Please clarify. I want to be sure I understand.” If the error is yours, ask for suggestions to correct it or offer alternatives of your own (separates criticism of performance from criticism of self). • The patient asks for personal information about you (or another staff member). You respond by saying, “That information is personal, and I do not choose to discuss it” (stands up for rights without violating rights of others). • Your patient asks you to pick up some personal items from the store. This would mean doing it on your own time, which is already very full. You respond by saying, “I will not be able to do the errand for you” (direct statement without excuses). • The team leader has been “on your case” constantly and, you think, unfairly. You approach the team leader and say, “I would like to speak with you privately today before 3 PM. What time is convenient for you?” (direct statement of wishes). • You are being pressed by other staff members to help with their assignments but are too busy to do so. You say, “No, I do not have the time to help today, but try me again on some other day” (direct refusal without feeling guilty; leaves the door open to help at a future date). • Your day is overwhelming. You approach your team leader and say, “I know you would like all of this done today. There is no way I can get it all done. What are your priorities?” (direct statement of information and request for clarification). • The doctor has criticized your work in front of the patient. You feel embarrassed and angry. You approach the doctor and ask to speak privately. Using “I-centered” statements, you begin by saying, “I feel both embarrassed and angry because you criticized me in front of the patient. Next time, ask to talk to me privately. I will listen to what you have to say” (stands up for your rights without violating the rights of others). • You are ready to leave work, when a peer approaches you about a personal problem. You respond by saying, “I have to leave now, but I’ll be glad to listen to you during our lunch break tomorrow” (compromise). • Another staff person moves into the cafeteria line ahead of you with a nod and a smile. You are in a hurry, too, and feel this is an imposition. You say firmly, “I do not like it when you cut in line ahead of me. Please go back to the end of the line” (stands up for your rights). Now complete the exercise in the Try This: Identify Assertiveness box. The following three rules are helpful overall in being assertive: Another negative interaction is based on a previous unresolved incident between the patient and the nurse. The nurse uses the coping or mental mechanism of rationalization, in which a logical but untrue reason is offered as an excuse for the behavior. The nurse quickly informs others that this patient is a “troublemaker” or a “manipulator” or “uncooperative.” This is a nonassertive, indirect type of behavior on the part of the nurse. Obviously, if other nurses incorporate this information into their transactions with patients, patients will never be seen as their true selves. Anything the patient does can be interpreted within the context of the label given by the nurses. A vicious circle can ensue. If the patient’s needs are not met because of this labeling, this increases his or her frustration. This in turn is a threat to self, resulting in anxiety. Depending on the patient’s personal strength at this time, the situation can lead to problem solving, the use of coping/mental mechanisms, or symptom formation (Figure 14-1).

Assertiveness

Your Responsibility

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Hill/success

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Hill/success

Nonassertive (passive) behavior

Aggressive behavior

Assertive behavior

Negative interactions: using coping mechanisms

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access