Early Complications

Complications following the surgical creation of an ostomy are a significant problem for many individuals. These complications are often multifaceted involving both physiologic and psychosocial aspects. The physiologic aspect of ostomy complications involves changes of the stoma and peristomal skin (Cottam et al., 2007). In this chapter, we discuss the physiologic aspect of ostomy complications involving the stoma.

Ostomy complications are a significant problem for individuals with an ostomy, yet, definitions and terminology are often not consistent in the literature (Colwell et al., 2001; Salvadalena, 2008). Study design differences, inconsistent definitions and terminology, and timing of measurements make it difficult to accurately measure ostomy complication incidence (Salvadalena, 2008). Due to inconsistent use of terminology, differentiating between stomal and peristomal complications can be difficult.

Overall incidence rates of complications have been reported, although the ranges are very broad. Two comprehensive systematic reviews of the literature on ostomy complications indicated that 18% to 55% of patients with an ostomy experienced peristomal skin irritation, 1% to 37% experienced parastomal herniation, 2% to 25% experienced stomal prolapse, 2% to 10% experienced stenosis, and 1% to 11% experienced retraction of the stoma (Colwell et al., 2001; Salvadalena, 2008). Ratliff et al. (2005) reported that 10% to 70% of all patients with an ostomy develop complications (Ratliff et al., 2005). Putting this into a practical perspective, using the estimates above, stoma complications represent a significant problem with up to 560,000 individuals who receive an ostomy experiencing ostomy-related complications. If we use the annual incidence, up to 84,000 individuals with a new ostomy can be expected to develop ostomy-related complications annually (Pittman, 2011).

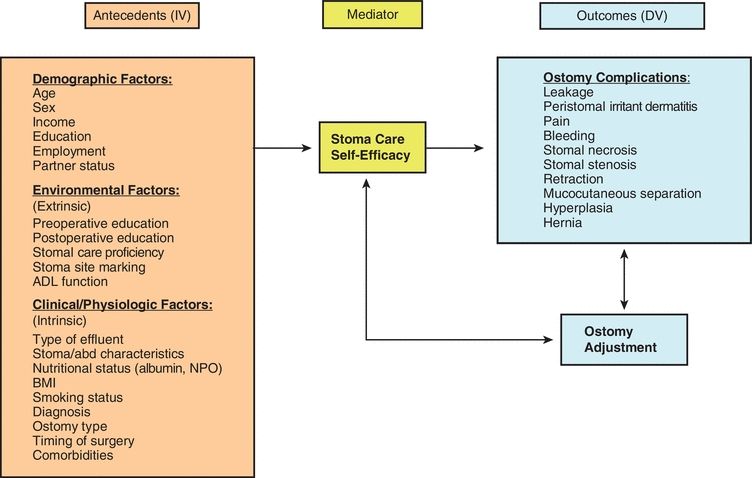

Various patient characteristics have been identified as being associated with ostomy complications, but studies with predictive analysis models are limited. Several studies have identified that higher body mass index (BMI), older age, emergent surgery, inflammatory bowel disease, having an ileostomy (vs. colostomy), a diverting “loop” procedure, poor bowel quality, ischemic colitis, stomal retraction, lack of preoperative education, and involvement of a wound, ostomy, and continence (WOC) nurse influence the development of ostomy complications (Bass et al., 1997; Colwell et al., 2001; Duchesne et al., 2002; Park et al., 1999; Pittman et al., 2008). In the landmark retrospective study conducted by Bass at Cook County Hospital in Chicago, complication rates were compared between patients who received preoperative education and stoma site marking by an enterostomal therapist (WOC nurse) and those who did not (Bass et al., 1997). They found that among those who received preoperative education and stoma site marking by an enterostomal therapist, 32.5% developed complications compared to 43.5% of those who did not receive these clinical interventions (p = 0.05). The Ostomy Complication Conceptual Model (Fig. 16-1) provides a framework for exploring ostomy complications and the risk factors that contribute to their occurrence (Pittman et al., 2014).

FIGURE 16-1. Pittman Ostomy Complication Conceptual Model.

One method of classifying ostomy complications is to separate them into early, within 30 days following surgery, and late complications, >30 days following surgery (Duchesne et al., 2002; Kim & Kumar, 2006; Park et al., 1999; Shabbir & Britton, 2010). In this chapter, we organize our discussion of stomal complications using this classification, recognizing that some complications can occur in both early and late time frames.

Early Complications

Early stomal complications are those that commonly occur within 30 days following surgery and include mucocutaneous separation, stomal necrosis, and stomal retraction.

Mucocutaneous Separation

Etiology/Incidence

Mucocutaneous separation is the detachment of stomal tissue from the surrounding peristomal skin (Colwell & Beitz, 2007) of the stoma, and mucocutaneous junction may be a result of poor healing, tension, or infection. Incidence of mucocutaneous separation has been reported to be from 4% to as high as 24%. Park et al. (1999) reported that 4% of patients had mucocutaneous separation in their review of 1,616 stoma patients (Park et al., 1999). In a prospective study of 3,970 stomas, Cottam et al. (2007) reported that 24% had mucocutaneous separation. In another study of 71 subjects, 13% had mucocutaneous separation (Pittman et al., 2014).

Presentation

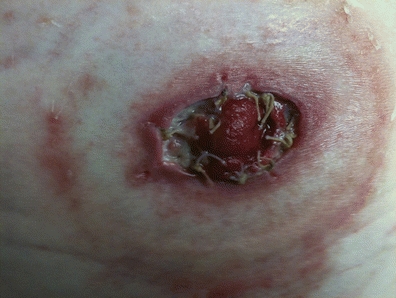

Healthy stomas will have a closely approximated and intact mucocutaneous junction (where the stoma is attached to the abdominal wall). As soon as 24 hours after surgery, the stoma and mucocutaneous junction may begin to separate.

Assessment

Assessment of the stoma is done by close visual observation of the stoma and integrity of the mucocutaneous junction. Separation is evident if the stoma detaches from the peristomal skin (Fig. 16-2). Mucocutaneous separation can occur in variable degrees of severity: partial—if it is only a portion of the stomal circumference, or complete—if the entire circumference is involved. The separation can also be superficial, only the skin level, or full thickness, extending to the fascia level (Franchini et al., 1983). Close observation of the area of separation is necessary noting depth, wound base tissue characteristics (necrotic, granular), and type of drainage (serosanguinous, purulent, fecal).

CLINICAL PEARL

Use a cotton tip applicator to assess the depth of the mucocutaneous separation.

FIGURE 16-2. Mucocutaneous separation.

Management

Management of mucocutaneous separation depends on the degree of the separation. If the separation is partial and superficial, the subcutaneous defect may be small and able to be managed conservatively. The subcutaneous defect may be treated like a wound and filled with an advanced wound product such as skin barrier powder, hydrofiber, or calcium alginate. The skin barrier of the pouching system is fitted over the peristomal skin and defect to provide protection from the stomal effluent. The pouching system is changed as warranted to manage the drainage, assess healing, and reapply the absorbent filler material (Colwell, 2004).

If the defect is large, then fecal contamination of the peristomal subcutaneous defect is likely and infection may occur. The more severe the separation, the more likely retraction of the stoma will occur. With healing, the likelihood of stenosis is high. If the mucocutaneous separation involves the fascial layer (a rarely reported occurrence), the stoma may drop into the abdominal cavity and contamination of the abdomen with fecal effluent and generalized peritonitis may occur. A return to surgery is indicated for repair.

Stomal Necrosis

Etiology/Incidence

Stomal necrosis is defined as death of the stomal tissue resulting from impaired blood flow (Colwell & Beitz, 2007) and has been identified as one of the most common early complications (Duchesne et al., 2002; Kim & Kumar, 2006; Park et al., 1999; Shabbir & Britton, 2010). Ischemia of stomal tissue is usually caused by tension on or inadequacy of the mesenteric vasculature to the intestinal end. It can also be caused by trauma to the stomal tissue during its creation. Stomal necrosis has been associated with obesity and is often a result of the traction that is placed on the mesentery and bowel wall (Colwell & Fichera, 2005).

Presentation

Impending stomal necrosis is evidenced by a progression of discoloration of the stomal tissue from pink to black. The stoma will usually appear dusky and dry within hours to days of surgery progressing to black and flaccid. The degree of necrosis may vary depending on the degree of ischemia. It may encompass the whole stoma, extending below the fascia, or only a portion of the stoma, and above skin level.

Assessment

Assessment of stomal necrosis is done by close visual observation. Within 24 hours of surgery, color changes of the stoma are usually visible. Color of the stoma progresses from dusky red to black (Fig. 16-3). To determine the degree or level of stomal necrosis, a clear, glass lubricated tube may be inserted into the stoma. Using a penlight directed into the glass tube, a change in the color of the stoma may be detected thus indicating the level of ischemia.

CLINICAL PEARL

It is advisable to use a clear pouch in the immediate post-operative period to allow for assessment of the stoma color.

FIGURE 16-3. Stomal necrosis.

A new innovative method of evaluating tissue perfusion is the intraoperative laser angiography using indocyanine green. This vascular imaging technology provides real-time assessment of tissue perfusion that correlates with clinical outcomes and can be used to guide surgical decision making (Gurtner et al., 2013). This method is primarily used intraoperatively to assess perfusion of the stoma and intestine at the time of resection.

Management

Stomal necrosis is often a watch-and-wait situation. If the ischemia and necrosis is above the fascial level, observation may be adequate. Often, if the ischemia and necrosis is superficial, the top layer of the stoma may slough off, leaving a red viable stoma. If the stomal ischemia and necrosis is below skin level but still above the fascial level, the necrotic stomal tissue will become malodorous and flaccid. Debridement is often indicated. After the necrotic tissue is removed or sloughs off, usually there is mucocutaneous separation. As the mucocutaneous separation heals, stenosis may occur. In addition, the level of the stoma above the skin is diminished, and this often leads to pouching challenges. If the ischemia and necrosis extend deeper than the fascial level, urgent surgical intervention may be indicated.

Stomal Retraction

Etiology/Incidence

Retraction is the disappearance of stoma tissue protrusion in line with or below skin level (Colwell & Beitz, 2007). Retraction is usually caused by tension on the stoma from a variety of reasons: short mesentery, thickened abdominal wall, excessive adhesions or scar formation, increased BMI, inadequate initial stoma length, or improper skin excision, stomal necrosis, and mucocutaneous separation (Colwell, 2004). Anecdotal evidence suggests that retraction occurs frequently in overweight patients with larger adipose layers. A shortened and fatty mesentery makes adequate mobilization of the bowel difficult, thus producing tension on the stoma (Cottam, 2005).

Ratliff and Donovan (2001) found that 9 (4%) of 220 ostomy patients had flush or retracted stomas. In a prospective study of 3,970 stomas, Cottam et al. (2007) reported that 40.1% had retraction. In Pittman’s prospective study of 71 participants with an ostomy, 24 (39%) had retraction (Pittman et al., 2014). In a 3-year retrospective study of 164 patients who had surgery resulting in an ostomy, retraction occurred in 5% of those patients (Duchesne et al., 2002). Another study of 97 patients with an ostomy found BMI to be associated with retraction (p = 0.003) (Arumugam et al., 2003). The incidence of retraction seems to be increasing. Cottam et al. (2007) reported that the incidence of stomal retraction (stoma below the skin level) more than doubled between 1996 and 2004 (22% vs. 51%) (Colwell and Beitz, 2007). In a systematic review of the literature, stoma retraction occurred in 9% to 15% of ileal conduits and 1% to 11% of all stomas (Szymanski et al., 2010). In Pittman’s study, patients who did not have their stoma site preoperatively marked by a WOC nurse experienced greater severity of ostomy complications, specifically stomal retraction (r = 0.32, p = 0.01) (Pittman et al., 2014).

Presentation

A healthy stoma should be above the level of the surrounding skin. In the past, there has been a misconception that colostomies should be flush with the skin. This has not been confirmed in the literature or in practice. In Cottam’s study of 1,329 problematic stomas, if the stoma height was <10 mm, the probability of having a problematic stoma was at least 35% (p < 0.0001) (Cottam et al., 2007).

Assessment

The stoma needs to be observed without the pouching system in place and in a variety of positions—sitting, supine, and standing. The level of the stoma and the surrounding skin needs to be closely noted. The stoma may disappear in a skin fold or crease when sitting or may become flush or even retracted with position changes and with peristalsis.

Management

The goal of successful pouching of the stoma is to have or create a flat pouching surface. When retraction is present, the goal is to augment the level of the stoma above the skin. This may sometimes be achieved using a convex pouching system and/or belt. If a predictable wear time is not achieved and complications continue, surgical intervention may be necessary to revise the stoma. Local revision may be possible if there is adequate intestine to mobilize above the skin level; if not, a more invasive surgery may be necessary to create a new stoma.

Late Complications

Late stomal complications are those that occur at least 30 days after surgery and often include stomal stenosis, prolapse, and parastomal herniation (Duchesne et al., 2002; Kim & Kumar, 2006; Park et al., 1999; Shabbir & Britton, 2010; Steel & Wu, 2002). With the advance of surgical techniques and laparoscopic surgery, various surgical techniques are being explored to minimize the risk of developing long-term complications (Gurtner et al., 2013; Heiying et al., 2014).

Stomal Stenosis

Etiology/Incidence

Stomal stenosis is the impairment of effluent drainage due to narrowing or contracting of the stomal tissue at the skin or fascial level (Colwell & Beitz, 2007). In the past, stenosis typically occurred early in the postoperative period due to inadequate surgical technique (at fascial level or at skin) or if not matured properly (Hampton, 1992). Due to the improvement in surgical technique, stomal stenosis is rarely seen early but rather late in the recovery process, >30 days following surgery, usually as a result of mucocutaneous separation, stoma necrosis, or retraction of the stoma. As healing occurs, formation of granulation tissue around the stoma constricts the lumen. Other causes of stomal stenosis include chronic disease (Crohn’s or tumor), excessive scar formation due to instrumentation (dilatation), or chronic inflammation (peristomal irritant dermatitis or hyperplasia) (Colwell, 2004; Hampton, 1992).

The incidence of stomal stenosis has been reported between 2% and 23%. Of the 316 patients studied, 10.2% were found to have stenosis (Cheung, 1995). In a retrospective study of 150 permanent end ileostomies, Leong and associates (1994) found 23% with stenosis. Pittman et al. (2014) identified 5% in her study of 71 ostomy patients, and Porter et al. (1989) reported a stenosis rate of 11%. In a retrospective study of 1,616 medical records from 1976 to 1995 of patients who had received ostomy surgery, Park et al. (1999) reported that 34% developed ostomy complications with 72% occurring late (more than 30 days postoperatively). The most common late complications were peristomal irritant dermatitis (6%), prolapse (2%), and stenosis (2%) (Park et al., 1999). Finally, in a 3-year retrospective study of 164 patients who had surgery resulting in an ostomy, 17% were reported with stenosis (Duchesne et al., 2002).

Presentation

The appearance of a stenotic stoma opening appears small (Fig. 16-4). Often the patient with a fecal stoma may report pain with stoma evacuation, small ribbon-like stool, or conversely, constipation followed by large explosive evacuations, loud with excessive gas. Patients with urostomies may report frequent urinary tract infections, projectile urine stream, and/or flank pain (Colwell, 2004).

FIGURE 16-4. Stomal stenosis.

Assessment

Assessment of a stenotic stoma is best performed with a gloved lubricated digit in order to assess the size and mobility of the skin and fascial rings. If a digit cannot be inserted into the stomal opening due to severe stricture, a retrograde contrast study through a small rubber catheter may be performed (Colwell, 2004).

CLINICAL PEARL

When assessing the stoma with a digital exam explain to the patient that the stoma does not contain nerves to cause pain, but if they should feel pressure to let you know so you can stop the exam.

Management

Management of mild stenosis of a fecal ostomy may include low-residue diet, stool softeners, or high liquid intake. Stoma dilation by gradually and incrementally introducing a dilator into the stoma has been a common practice in the past, but there is little evidence in the literature to support this practice. However, chronic dilation has been reported to potentially cause stomal stenosis (Hampton, 1992). Stomal dilation can be used to temporarily aid in evacuation but is not recommended as a long-term practice. For the most severe cases, surgery is warranted. This may involve freeing the stoma from the peristomal skin locally or by performing a laparotomy/laparoscope and resiting the stoma.

Stomal Prolapse

Etiology/Incidence

Stomal prolapse is the telescoping of the intestine through the stoma (Colwell & Beitz, 2007). Prolapse of the stoma can occur for a number of reasons: increased abdominal pressure, obesity, the stomal opening in the abdominal wall is too large, or the stoma was created outside the rectus muscle (Weideman et al., 2012).

All stomas are subject to prolapse, and incidence reports vary. Stoma prolapse is often seen in loop colostomies, and the distal limb is predominantly involved (Shellito, 1998; Gordon et al., 1998). Cheung (1995) reported that 6.8% developed prolapse in 156 end-sigmoid colostomies. In a study of 130 subjects with an end colostomy over a 6-year period, 4% experienced prolapsed stoma (Porter et al., 1989). Stomal prolapse is often seen in children (Franchini et al., 1983; Steinau et al., 2001). In a study of 144 infants with anorectal malformations, the incidence of stomal prolapse was higher in those with loop versus divided colostomies, 17.8% and 2.8%, respectively (p = 0.005) (Oda et al., 2014). Chen et al. (2013) performed a meta-analysis including five randomized controlled trials and seven nonrandomized studies with 1,687 patients in total comparing outcomes in temporary ileostomies versus temporary colostomies. They found a lower incidence of stoma prolapse in temporary ileostomy patients compared to temporary colostomy patients in both randomized control trials and nonrandomized trials (RR 0.15, 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.48, p = 0.001 and RR 0.26, 95% CI: 0.10 to 0.67, p = 0.005, respectively) (Chen et al., 2013). In a systematic review of the literature related to stoma complications following radical cystectomy and ileal conduit diversions, stomal prolapse was identified in 1.5% to 8% at a mean of 2 years following surgery (Szymanski et al., 2010). It has been reported that up to 50% of patients with prolapsed colostomy also had a parastomal hernia (Kim & Kumar, 2006).

Presentation

A prolapsed stoma can present in a variety of degrees of severity and length of stomal protrusion (Fig. 16-5). The length of the prolapsed stoma will guide management. The greater the length of the prolapse, the greater the likelihood of stomal edema, trauma, and ischemia. As the stoma becomes edematous and dependent, it becomes a deep red color (vasodilation). With a very prominent (5 to 13 inches) prolapse, the stoma is susceptible to trauma. Care needs to include avoiding friction, laceration, or pressure to the stoma. In extreme situations, blood supply to the stoma may become compromised and stomal ischemia may occur.

FIGURE 16-5. Stomal prolapse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Late Complications

Late Complications Conclusions

Conclusions