Sarah Hargrave, Corrine Olson and Frances A. Maurer

State and Local Health Departments

Focus Questions

What are the core functions and essential services of public health?

What are the responsibilities of the state health agency and local health department?

What is the impact of funding sources on public health services to communities?

What health services and populations have traditionally been a focus of public health nursing?

How is nursing in local health departments organized?

What are the various responsibilities of the public health nurse in the local health department?

What are future trends for nursing in state and local health departments?

Key Terms

Core functions of public health

Direct health care services

Essential public health services

Local health department (LHD)

MAPP Model

Population-based health services

Public health infrastructure

State health agency (SHA)

Superagency

Core Functions and Essential Services of Public Health

Under the U.S. Constitution, states retain the power to protect the health and welfare of their residents (see Chapter 3). Consequently, states have the primary responsibility for public health functions. They address these responsibilities through the state health agency (SHA). States delegate some of that responsibility to local health departments. Thus in the United States, state and local health departments perform the major portion of public health activities. The 1988 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report titled The Future of Public Health indicated public health functions were poorly focused and the public health infrastructure was inadequate. It further noted that funding for public health was sporadic and inadequate to meet the needs of the nation’s health. In 2003 another report noted that fragmentation, inadequate funding, insufficient accountability, and lack of partnerships with other health care service providers persist (IOM, 2003).

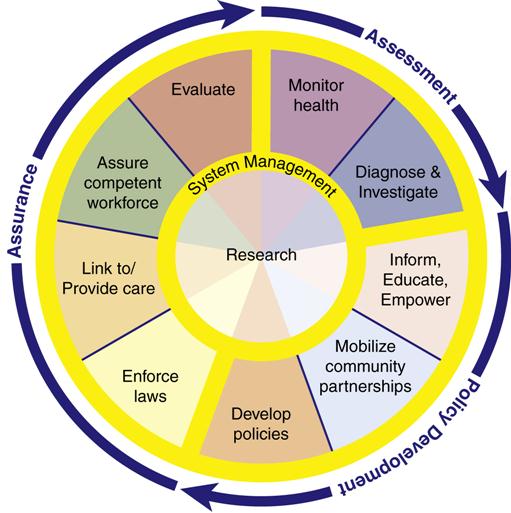

The Institute of Medicine study identified three core functions of public health. Subsequently, the Essential Public Health Services Work Group (1995) identified 10 essential public health services necessary to meet these three core functions (Figure 29-1). Both the core functions and 10 essential services focused on population-based care as opposed to direct health care to individuals—for example, communicable disease surveillance as opposed to home health care to an ill individual. The following are identified as critical public health responsibilities:

• Preventing epidemics and the spread of disease

• Protecting against environmental hazards

• Promoting and encouraging healthy behaviors and mental health

• Responding to disasters and assisting communities in recovery

• Ensuring the quality and accessibility of health services (Essential Public Health Services Work Group, 1995)

In response to the Institute of Medicine report, public health practice has made substantial change. There is an emphasis on population-based care and the development of coalitions and partnerships to provide health care to populations. Healthy People 2010 added additional public health objectives, and made improvement of the public health infrastructure a key objective. Healthy People 2020’s objectives emphasize health equity, determinants of health, and collaboration across public and private sectors to improve the health status of the American population.

Funding for public health functions remains a problem. All governmental agencies combined spent $77.2 billion to provide essential public health services in 2009 (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2011a). Today, public health funding remains low, 3% of the total health care budget. Funding is provided by state and local governments (47%), and the remainder by the federal government, fees, and other sources (National Association of County and City Health Officials [NACCHO], 2011a). Despite a renewed emphasis on population-focused care, only 24% of public health funds is used for population-based public health services. The remaining 76% is spent on providing direct individual care or linking people to direct care. Shi and Singh (2011) estimated the amount of all government funds spent on population-based care at $149 per person per year, a very minimal amount.

Despite sporadic funding and changes in the focus of care, public health efforts have produced significant success in the past decade. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011a) has identified the following public health achievements between 2001 and 2010:

• Prevention and control of infectious diseases

• Cardiovascular disease prevention

• Childhood lead poisoning prevention

Much of the improvements in these 10 health areas are the result of state and local health departments.

Impact of Terrorism on Public Health Responsibilities

September 11, 2001, brought renewed resolve to the effort to improve public health surveillance and infrastructure (Madamala et al., 2011). The anthrax attack that same year solidified interest in improving public health population-based functions. Federal funding past 9/11 increased in the area of disease surveillance and emergency preparedness. However, in subsequent years between 2002 to 2006 federal monies were reduced (Landers, 2007). Starting in 2007 federal funding improved again. For example, in 2007 state health departments received approximately $896.7 million in federal funds to prepare for and respond to terrorism, infectious disease outbreaks, and other public health threats and emergencies (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2007). Funding levels remained stable for 2008 to 2009 at $861 million and at $842 million for 2010 with the focus moving toward law enforcement (U.S. Department of Homeland Security [USDHS], 2008, 2009, 2010).

All 50 SHAs indicate persistent problems with resource allocation, staffing, and surveillance (National Governors Association [NGA], 2004, 2007). The federal government has added responsibilities for emergency preparedness to SHAs without consistently funding these responsibilities. The CDC (2011b) has issued a national strategic plan for preparedness that has added additional preparedness responsibilities to state and local health departments. As a result, SHAs have had to reassign resources and personnel from other program areas, thus reducing services in those areas (Bashir et al., 2007; Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2009). This has exacerbated problems inherent in public health services and programs. The Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2003) issued a second study titled The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century, which provides additional recommendations for strengthening the public health system in the United States. The CDC (2000) status report to the U.S. Senate indicated the following three critical areas for improvement necessary to strengthen the public health infrastructure:

It is important to review the present state of public health in the United States in the wake of current events and in light of the concerns and recommendations from the public health community. State and local health departments are the essential units of public health service delivery and the subject of this chapter.

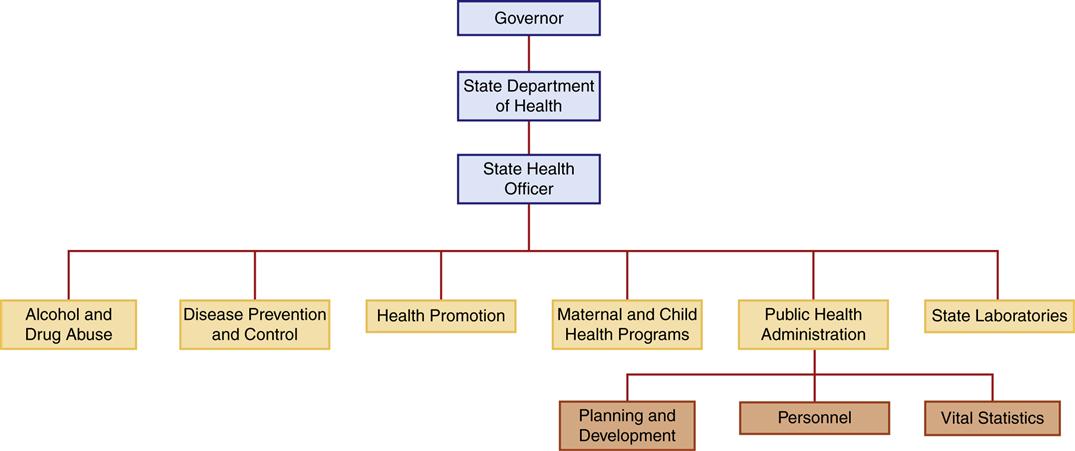

Structure and Responsibilities of the State Health Agency

Each of the 50 states has an SHA, usually called the state health department. The structures of these agencies vary dramatically. The majority of states have freestanding, independent health agencies. There is a movement toward integration into a larger “superagency” such as a health and human services department (Beitsch et al., 2006). Currently 22 state health agencies are merged into superagencies (Association of State and Territorial Health Officials [ASTHO], 2010). Chapter 3 has an organizational chart for a state superagency with health responsibilities. Figure 29-2 is an example of the organizational structure and functions of a state health department.

The chief executive of an SHA is the state health officer/director. Most are political appointees, serving at the discretion of the state’s governor. Many are physicians. In some states, the health code requires a physician to serve as the health officer; in most it has been a matter of tradition. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) (2010) reports that fewer states are requiring a medical degree for the state health officer/director. Currently one-third of state health officers hold degrees in public health.

A state health agency either provides or funds direct client services for select populations, usually the economically disadvantaged (for example, low-income pregnant females or young children). It may also administer care for institutional populations, such as older adults (nursing homes) or mentally ill (state mental hospitals). The IOM (1988) has made it clear that the states are the central force in maintaining public health. Most states meet these requirements and their other assigned obligations through the combined efforts of the SHA and local health departments. In most instances, the SHA assists, delegates to, and/or oversees local health departments. The services provided by state and local health departments are a mix of direct health care to select populations and core public health functions to communities (Box 29-1). Other state and local agencies may assume primary responsibility for some portion of these services, such as mental health, professional and institutional licensure, and environmental health. A review of recent reports shows more states have increased emphasis on health planning and development, quality improvement and performance management, bioterrorism preparedness, and emergency medical services’ oversight, and have attempted to reduce direct care services (ASTHO, 2010; Beitsch et al., 2006; Madamala et al., 2011; NACCHO, 2011a).

Funding of State Health Agencies

Most funding for SHAs comes from public tax dollars provided by the state and federal government. States vary in the degree to which they fund public health and population-focused activities. Public health expenditures are a small percentage of state spending. In 2009 public health expenditures for all activities including SHAs were $65 billion. Public health expenditures represented only 4.3% of the $1.5 trillion spent by all states in 2009 (CMS, 2011a; National Association of State Budget Officers [NASBO], 2010).

State budgets for health and welfare programs have been squeezed by several factors. In the past 3 decades, federal funding to SHAs has been reduced and concentrated in block grants. This action by the federal government was intended to give states more control over their programs as well as put limits on federal spending for health and welfare programs. In actuality, states have experienced a reduction in the proportion of federal funding provided for state health and welfare programs and additional constraints on how federal funds are spent (Fee & Brown, 2002; Chapter 4). Turnock (2009) reports that block grants resulted in a 25% reduction in federal funds to state and local health agencies. Funds for public health activities were included in the reductions in federal support. At the same time, state sources of money (the state tax base) were strained. State income sources have not kept up with state responsibilities, because of a downturn in the economy and as a result of tax reform efforts and pressures to improve disaster preparedness and response (ASTHO, 2010; Madamala et al., 2011; NACCHO, 2007). Consequently, SHAs have experienced budget cuts and staffing reductions, and have had to reduce services to individuals and communities.

Liaison of State and Local Public Health Agencies

Each state specifies its relationship with local health departments (LHDs), with some states being more centralized than others. The SHA coordinates efforts of all the local departments (for example, oversight of communicable disease reporting and control) and provides some of the funding for the LHDs. In some states, the LHD is an agency within the SHA; however, most LHDs are more autonomous, either consulting with the state or directly planning programs and setting health policy for the communities they serve. In most states with LHDs, direct health care services are primarily provided at the local level.

SHAs may provide some direct care, but they are more involved in the development and oversight of health-related regulations, coordination of statewide health assessments, and monitoring the health of special-risk populations. Although both state and local health departments provide vital services to guard the public’s health, the more visible services are provided at the local level. LHDs provide most of the direct care to clients and communities.

Structure and Responsibilities of Local Public Health Agencies

Local health departments obtain their authority through state law and additional local ordinances. Whatever the organizational structure, it is LHDs that directly provide public health services to community residents.

Each LHD carries out the three core functions of public health (see Figure 29-1). Healthy People 2010 specifically listed these core functions as objectives for local health departments. Healthy People 2010 (USDHHS, 2000) increases the emphasis on public health, stressing the need for both state and local health department involvement in improving public health infrastructure, data collection, and service to the population and risk groups. The three core public health functions serve as the foundation for these new public health objectives (see the Healthy People 2020 box on page 730).

Types of Local Public Health Departments

An LHD has been defined by the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO, 2009, p. 3) as “an administrative or service unit of local or state government concerned with health and carrying some responsibility for the health of a jurisdiction smaller than the state.” There are five major types of LHD: county, city, city-county, township, or multi-county/region. County LHDs are the most common type. City health departments are the least common. Multicounty health departments span large geographical areas and are more common in the western United States. For example, the Northeast Colorado Health Department serves six counties in Colorado. Website Resource 29A

![]() provides several examples of the organizational charts for different types of local public health agencies (LPHAs).

provides several examples of the organizational charts for different types of local public health agencies (LPHAs).

NACCHO reports the following information concerning LHDs:

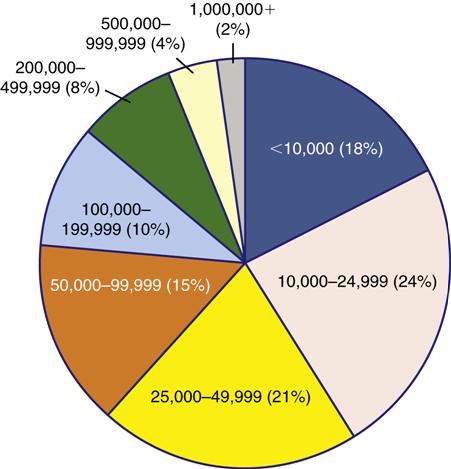

• Two-thirds of the LHDs serve jurisdictions of fewer than 50,000 people, and 5% serve populations of 500,000 or more (Figure 29-3).

• Sixty-eight percent of LHDs are county based.

• Ninety-six percent of LHDs report employing full- or part-time registered nurses either directly or through contracted services (NACCHO, 2011a).

Funding Sources

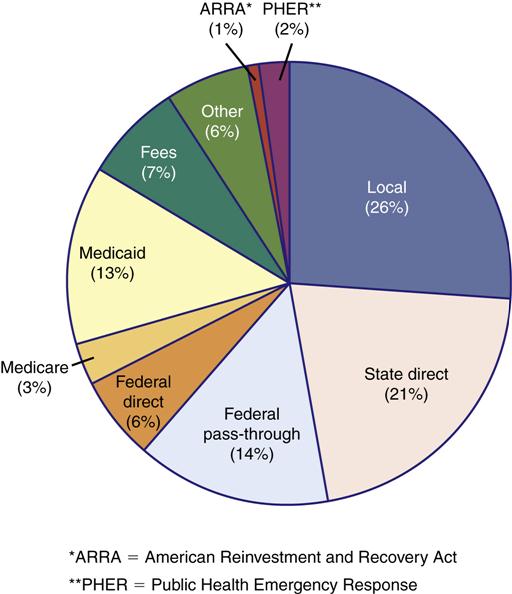

The funding source for LHDs is a combination of local, state, and federal funds (Figure 29-4). In addition, LHDs may collect fees from clients who receive direct personal health care services and from regulatory or licensing fees. For example, a health department responsible for inspecting restaurants to ensure food safety may collect fees as part of the food permit process.

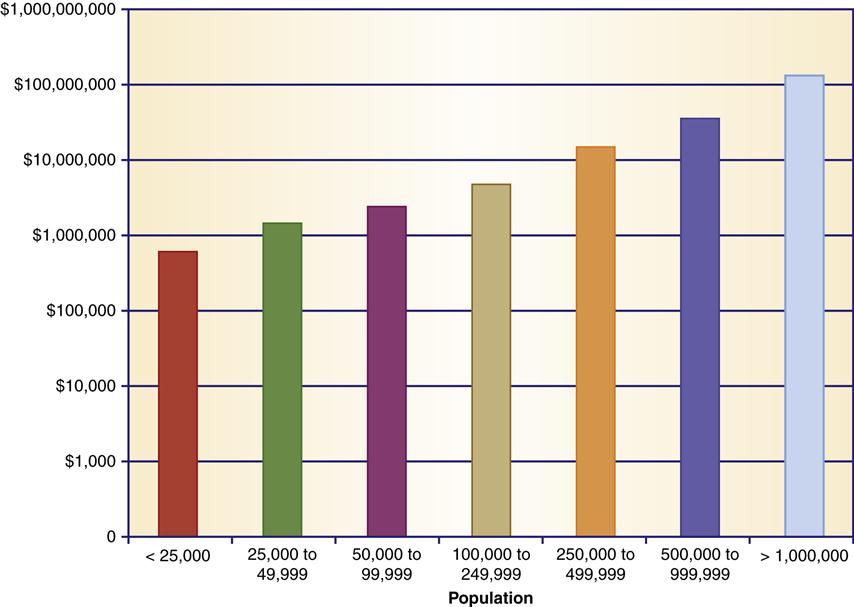

Budgets for LHDs range from less than $25,000 to more than $5 million (NACCHO, 2011a). LHD budgets represent less than 1% of the total national health care budget (see Chapter 3). Local public health costs are estimated at approximately $36 to $48 per community resident (NACCHO, 2011a). For the most part, LHDs that serve larger populations have bigger budgets and are more reliant on state and local funding and less on Medicare and Medicaid (Figure 29-5). Thirty-one percent of all LHDs have budgets of $1 million or less per year (NACCHO, 2011a).

Local Funds

Revenue coming from local sources is primarily from taxes or a levy. A levy is a mechanism for raising money through the ballot box. It is similar to a bond issue in that it is a determined percentage of the local property tax or a local income tax approved by voters. Because general tax money fluctuates with the strength of business and industry in the community, a levy must be placed on the ballot periodically for voter approval.

Many states have a legislatively allocated LHD subsidy of a few cents to a few dollars per capita. This subsidy is derived from a state’s general fund, which comprises taxes, fees collected, and grant monies that do not have a specified expenditure. This is not sufficient to support LHD programs but is important in the total financial scheme.

Although most LHDs collect fees, these fees account for a small portion (7%) of the total budget (NACCHO, 2011a). The larger the LHD, the less likely it is to collect fees for services. Fees are collected for most health, environmental, counseling, and birth and death registration services. Many nursing services also have a service fee. A sliding fee scale is used to determine what percentage of the fee the client will pay based on the client’s financial assets. Generally, service fees are not sufficient to fully cover the cost, but if a client cannot pay, service is not denied. If a client has a third-party payer (e.g., Medicaid or private health insurance), some departments will bill that source or provide the client with a receipt to file for reimbursement. Fees may be used within the department to partially support health and environmental services. Such money might also become part of the jurisdiction’s general funds. Medicare and Medicaid funding sources are becoming less available as direct health services to at-risk populations continue to be contracted out to managed care organizations. For example, many LHDs once operated clinics that provided care to sick children, and, as such, collected Medicaid fees for treating those children who were Medicaid eligible. Most LHDs now contract with managed care organizations to provide such services and no longer collect Medicaid fees. In addition, if an LHD has redirected their well-child services to a managed care organization, they no longer collect Medicaid payments for immunizations to Medicaid-eligible children. Three-fourths of LHDs have contracts with at least one private agency to provide personal health services.

Federal and State Funds

State and federal monies account for almost 41% of LHD funds (NACCHO, 2011a). Some of the state money is passed from the federal government. These federal funds are intended to finance certain programs or services, and the states act as the oversight authority for the federally supported services.

Impact of Federal and State Budgets on LHDs

The federal and state portion of the LHD budget has decreased approximately 4% since 2005 (NACCHO, 2006, 2009). These decreases have impacted services. Funding allocations are the result of changing governmental policies and shrinking tax revenues. The federal block grant process has limited funding to programs administered by both state and local health departments (Chapter 4). Federal block grants and cutbacks in other federal health-related funding have stressed state government budgets (Madamala et al., 2011). States have been forced to assume more responsibility for health and welfare programs. These changes have a domino effect as federal reductions in contributions to state budgets force states to provide fewer dollars to local departments through which most of the public health care services are provided. Finally, the economic recessions of the late 1990s and early 2000s and of 2010 to 2011 as well as the shrinking value of property have reduced tax revenues, impacting both budget and service at all three levels of government.

Impact of Funding Variation

Most LHDs rely on several funding sources; some may attach specific conditions to the use of funds. The cost to the department of the restrictions and accountability imposed by the grantor may exceed the benefits obtained with the money. Staff hired with grant money must work on that program only, or the work time of the numbers of people providing part-time services must equal the full-time equivalent. When money is no longer available or is cut, jobs paid by those funds may be lost. Some funds cannot be used for rental space, building, or equipment purchases. If equipment can be purchased, those items may be claimed by the funding sources when money allocation is terminated. Reports and data for federal or state money, which must be collected and reported in a set format, frequently duplicate data collected at the local level—all in a different format. Nursing and other personnel may spend time in producing redundant paperwork rather than providing services to clients and communities.

Local health department costs—salaries, supplies, equipment, and benefits—increase annually. However, the amount of appropriations often remains the same over time or is reduced. Thus, the degree to which this money actually supports local services is decreased (NACCHO, 2010a). In the difficult economy of the late 1990s through the early 2010s, the demand for public health nursing services has increased. Local health departments are continually challenged to be innovative, creative, flexible, and available.

At one time, LHDs tried to avoid having nursing and/or other staff on time-limited, or “soft,” money, but currently, staff may be paid by two or three funding sources. This is where the full-time-equivalent factor enters the equation. Community health nursing administrators address difficult questions as they modify budgets. What components of a perinatal or child health program can be financed by other money when a funding source ends or decreases? When child health funds do not keep pace with costs, how can sufficient child health services be incorporated into the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program? Similar questions arise for all public health nursing services. With flexible hours and flexible staffing, two part-time employees can fill a full-time position. If possible, other types of employees, such as nursing assistants, may be hired to perform nonnursing tasks and allow more efficient use of nursing time.

Impact of Legislation

The funding sources discussed previously are considered legislative, except for foundations. State and federal agencies and programs have evolved through legislation. The appropriations are made or withheld based on state and federal budget emphases, the interests and power of legislators, and the demands of lobbying groups and constituents.

Both federal and state legislatures and agencies are skilled at passing health-related bills or issuing health-related directives without appropriate funds to implement the program. One example involves the use of the WIC program to monitor childhood immunizations. Studies indicate that linking WIC and children’s immunization services is an effective strategy (Briss et al., 2000; Hutchins et al., 1999). Children seen for WIC services were reviewed to determine immunization status. Those found deficient were either immunized at the WIC center or referred to other sources for immunization. The costs of providing these services at each WIC site ranged from $19,500 to $60,300, depending on staff requirements. The preliminary studies were done with grant money. In 2000 a presidential directive required the WIC program to implement immunization screening and referral at all WIC sites (Shefer et al., 2002). In 2010 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services directed states to provide Medicaid coverage for tobacco-cessation counseling and drug therapy for pregnant women (NACCHO, 2010b). No additional money was allocated for the additional staffing and administrative requirements for either directive.

Public health employees are becoming more effective working with legislators. Public health nurses, environmentalists, administrators, and other staff working with programs such as substance and alcohol abuse, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) case coordination organize networks to initiate, support, or oppose legislation that will adversely affect LHDs and communities. For example, in a number of states, public health professionals have been highly effective in guiding and supporting specific HIV testing and AIDS legislation. The bills afford protection for health care workers by the availability of HIV tests and employment security if that test is positive. Public health advocates have been equally effective in opposing broad AIDS legislation that would compromise an individual’s privacy, employment, and/or health insurance coverage (Roseau & Reomer, 2008).

Geographical Variations in Services and Funding

As noted earlier, most local public health programs serve populations of 50,000 or less. All the factors noted within this chapter heavily influence the needs of and services for rural areas and small towns in the United States.

Medical personnel and health services are often concentrated in urban areas and in group medical practices in the United States. Group practices afford individuals access to the care they may need, be it family medicine, internal medicine, or another specialty represented in a group practice. This sounds beneficial to the client. This geographical maldistribution of physicians has led to inner-city and rural areas being medically underserved, although there has been a slight improvement in physician supply in rural areas (Smart, 2006). These areas may attract only the single-specialty physician, who may practice alone in communities with great needs. Some communities with populations of 15,000 to 30,000 have only one physician. Even the state health department may not have clinics in inner-city areas or some rural communities. Transportation problems and appointment times that conflict with employment can be added barriers (see Chapter 32).

Public health nurses in rural communities and city health departments provide wide-ranging wellness care and health screening to detect potential problems. An important component is education regarding health-promotion and lifestyle adaptations that reduce risks to good health. Nurse practitioners monitor and/or treat illnesses and chronic diseases depending on the support of the department’s medical director and on community needs. Because most public health nurses are long-term residents of their community, they know their community.

Some state health departments, through maternal and child health programs, may provide itinerant multidisciplinary teams of specialists for diagnosis and treatment of infants and children with disabilities. The local public health nursing staff provides follow-up, case management, advocacy, and continuing family and client support and guidance.

Staffing of Local Public Health Agencies

The LHDs may have a staff as small as one public health nurse, one environmentalist (sanitarian), and one part-time health director, or it may employ hundreds of employees to meet major city and jurisdiction health and environmental needs. The staff may comprise public health nurses, nurses in expanded roles (e.g., nurse practitioners), nutritionists, environmentalists, health educators, a biostatistician, clerical and laboratory staff, nursing or home health aides, counselors for alcohol and substance abuse, the health director, physicians, and various administrative staff. States also vary regarding whether the chief administrative officer is required to be a physician. The duties of public health personnel are both direct individual and population-focused care.

A health department may be a combined agency, having both wellness services and home health services for ill and disabled persons. Combined agencies may employ or contract for physiotherapists, home care aides or nursing assistants, nutritionists, social workers, speech or occupational therapists, and others.

Public Health Nurses

Previous chapters have dealt with the definition and scope of community/public health nursing and its many facets for nursing practice (see Chapters 1 and 2). Aside from administrative staff, community/public health nurses are the single largest professional staff in LHDs (NACCHO, 2011a). This has been true since the 1920s, when many local governments (counties, cities, or multi-county regions) developed health departments to promote the health of the people residing in their jurisdictions. Although the terms community health nurse and public health nurse are used interchangeably, nurses working for government-sponsored (public) entities often prefer the original name, public health nurse (see Chapter 2).

Public health nurses were and are professionals who attempt to develop healthful communities through population-based practice. An ecological approach toward public health nursing recognizes the influence of determinants of health on multiple layers including individuals, families, communities, organizations, and social systems (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007). Public health nurses may simultaneously target individuals, families, communities, or systems with their interventions, as the focus of their work is the population as a whole. Public health nurses emphasize primary prevention of “illness, injury or disability, the promotion of health, and maintenance of the health of populations” (American Public Health Association [APHA], 2007). Public health nursing will be addressed in greater detail later in this chapter.

Environmental Sanitarians

Environmental sanitarians are concerned with safe air, water, food, and housing. They conduct routine sampling of air and private water sources and inspect restaurants, dairies, and food processing sites. Sanitarians provide environmental education, enforce environmental laws, and respond to complaints. They may collect residential paint samples for lead analysis and address noise, unsafe dwellings, rodent control, and hazardous wastes.

Biostatisticians and Epidemiologists

Biostatisticians and epidemiologists apply their knowledge of statistics and the natural history of diseases to describe the health of communities, explore the causes of specific disease outbreaks, predict health hazards, and evaluate interventions. These health specialists are employed primarily at the state level or by larger LHDs. In response to terrorism and emergency preparedness, federal funding rapidly increased the number of epidemiologists at the state level starting in 2001 and through the present. However, state public health officials estimate that 34% more epidemiologists are needed nationwide to fully staff terrorism preparedness programs (CDC, 2008a).

Environmental issues and communicable disease control remain LHD mandates and priorities. Food and water sanitation and vector control exist alongside such modern concerns as hazardous waste management and swimming pool inspections. When a food-borne or water-borne disease is reported, the public health nurse and environmentalist work together to discover the source, follow-up with people reporting illness or symptoms, refer them for medical treatment, provide education and get the problem under control.

Services Provided by the State Health Agency and the Local Health Department

As previously stated, SHAs and LHDs are partners in ensuring the public health of their citizens. According to the ASTHO (2010), the main services provided to meet that goal are as follows:

• Collect vital statistics and analyze statistics

• Ensure environmental health and safety

• Provide laboratory facilities

• Access to health care for minority populations

• Ensure emergency and disaster preparedness

• Provide maternal and child health care

Most of the services are coordinated. The collection of vital statistics, for example, begins at the local level. The state collects individual local reports and coalesces this information into a report of the statewide status of births, deaths, marriages, and so on. Many of the other services provided by state and local health agencies are discussed later.

Disaster Preparedness

Since 9/11 emergency preparedness is a critical focus of all levels of government including SHAs and LHDs (see Chapter 22). In response to the CDC (2011b) and the USDHS, LHDs have implemented or improved in three areas: emergency preparedness, emergency exercises, and workforce development.

In 2008, 82% of LHDs had emergency response plans in place as compared to 20% in 2001. In addition many have advanced plans for rare but potentially lethal attacks such as smallpox, anthrax, and pandemic influenza (NACCHO, 2008). Most LHDs (86%) have conducted drills/exercises to test out personnel, equipment, and communications systems (CDC, 2008a). Workforce development has been slower and needs significant improvement. Only 36% of LHDs have completed a needs assessment for personnel and 60% report they do not have enough personnel dedicated to preparedness efforts (NACCHO, 2008). The funding problems discussed earlier at both the state and local levels have slowed progress in all three areas listed above.

Personal Health Care

In addition to population-based health care such as control of communicable diseases and injuries, promotion of wellness and reduction of risks to health and community data may also dictate the need for primary care. Primary care is the provision of personal health services to individuals and family members, including screening and referral, health maintenance, long-term management of chronic disease, and care for acute illnesses.

In the early 1980s, as a response to increases in the number of medically uninsured and underinsured people, more health departments became directly involved in providing primary care services. Starting in the early 1990s, LHDs began to reassess and redefine their role in health care delivery in line with the IOM recommendations. A renewed focus on population-based health services has resulted in a reduction in direct personal health care by LHDs. Today, LHDs still provide direct care, although many are attempting to redirect these types of services to other organizations such as managed care (Gollust & Jacobson, 2006). For example, the state of Maryland redirected its well-child and sick-child care to specially contracted managed care organizations. The managed care organizations are paid to provide specific screening and immunization services for well-children. They also provide specific illness and rehabilitative services up to a certain dollar amount for children with health problems. Some of the state and local public health nurses act as case managers to oversee and coordinate additional services for children with special needs.

Redirecting or eliminating direct personal health care services is influenced by the geographical area and availability of other health care resources. Nonmetropolitan areas are more likely to have problems finding alternative sources for direct care. In 2010, 25% of LHDs provided home health care services to community members, a 30% decline since 1993 (NACCHO, 2001, 2011a). However, twice as many nonmetropolitan LHDs still provide home health care as do metropolitan LHDs.

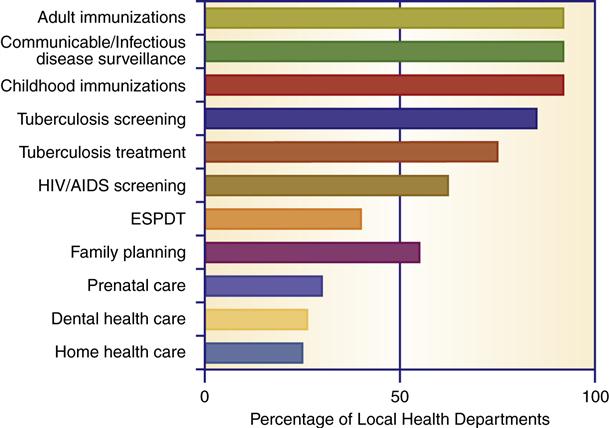

Figure 29-6 illustrates the types of direct care provided by various LHDs. Aside from screening services, the bar graph shows that personal services are provided by fewer LHDs today than in 1993. For example, HIV/AIDS treatment was provided by 32% of LHDs in 1993, and only 21% still provide direct care in 2010. Family planning services were provided by 68% of LHDs in 1993 and 55% in 2010 (NACCHO, 1995, 2011a).

EPSDT, Early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment. (Data from National Association of County and City Health Officials. [2011]. 2010 National profile of local health departments. Washington, DC: NACCHO.)