Somatic Therapies

ECT is the most effective and rapidly acting treatment for major depressive disorder and plays an important role in the treatment of geriatric patients, but its use is limited by cognitive and other side effects.

Despite studies proving efficacy, it [ECT] remains the most controversial treatment in psychiatry.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Compare and contrast the rationale for the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and magnetic seizure therapy (MST).

Explain the ECT procedure.

Identify the indications for using ECT.

Explain the conditions associated with increased risk during ECT.

Recognize the presence of ECT adverse effects.

Describe advances in ECT.

Formulate nursing interventions to prepare a client for ECT.

Key Terms

Clitoridectomy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Electronarcosis

Insulin shock therapy

Lobotomy

Magnetic seizure therapy (MST)

Physiotherapy

Postictal agitation

Psychosurgery

Somatic therapy

Sterilization

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)

The biologic treatment of mental disorders is referred to as somatic therapy. In the early 20th century, various somatic procedures, such as lobotomy, sterilization, clitoridectomy, and insulin shock therapy, were performed to treat the mentally ill client. Physiotherapy, a noninvasive procedure, is another type of somatic therapy that was utilized in the psychiatric clinical setting.

Although the potential for major physiologic complications and death existed, physicians performed these techniques in an attempt to minimize disordered behavior by locating their perceived origins in the body (Ginther, 1998).

Lobotomy, also called psychosurgery, is a surgical intervention that originated in 1936. This invasive surgery severs fibers connecting one part of the brain with another, or removes or destroys brain tissue. It is designed to affect the client’s psychological state, including modification of disturbed behavior, thought content, or mood. Currently, prefrontal lobotomy and transorbital lobotomy are two types of psychosurgery still used in research and treatment centers for clients with chronic disorders and those who have not responded to other recommended approaches.

Sterilization, ligation of the fallopian tubes in a woman and excision of a part of the vas deferens in a man, and clitoridectomy, surgical removal of part of the clitoris, were invasive procedures performed predominantly on female clients who exhibited “inappropriate” or aggressive sexual behavior.

Manfred Sakel, who believed that nervous hyperactivity occurring in morphine withdrawal was caused by an excess of epinephrine, developed insulin shock therapy in 1928. He postulated that this therapy, which uses large doses of insulin to decrease glucose levels to induce hypoglycemia or insulin coma, would also depress the levels of excess epinephrine and stabilize the hyperactivity. Sakel then expanded his theory to include the treatment of excitation exhibited by clients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia. The use of insulin shock therapy rapidly declined in the 1970s and has since been replaced by clinical psychopharmacology and psychotherapy (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Physiotherapy is the application of hydrotherapy and massages to induce relaxation in clients. The effects are short lasting, and the treatments produce few adverse effects if any. In the past, hydrotherapy by the application of wet packs and cold sheets was used to treat agitation and depression. Clients were also placed in tubs of hot or cold water to induce relaxation and decrease agitation. A partial tub cover served as a restraint when the client sat or reclined in the tub. Present-day hydrotherapy includes the use of hot baths, whirlpool baths, showers, and swimming pools.

Present-day somatic therapies include clinical psychopharmacology (see discussion in Chapter 16), phototherapy (see discussion in Chapter 21), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Two investigational therapies that are considered an alternative to ECT are transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and magnetic seizure therapy (MST). This chapter focuses on the history of ECT, use of ECT in the psychiatric clinical setting, including a description of the procedure, indications and conditions associated with increased risk during its use, adverse effects, advances in the technique, guidelines for ECT, and nursing interventions. A discussion of VNS, TMS, and MST is also included.

History of Electroconvulsive Therapy

Hall and Bensing (2005), Fink (2004), and Sadock and Sadock (2003) provide an excellent overview of the discovery and evolution of ECT. Although electric eels were used to ease headaches and camphor-induced seizures were used to treat psychosis as early as the 16th century, most histories of ECT start in 1934, when catatonia and other schizophrenic symptoms were successfully treated with pharmacologically induced seizures. Before the introduction of ECT, intramuscular injections of camphor suspended in oil and then the intravenous administration of pentylenetetrazol were used to induce seizures. In 1938, Cerletti and Bini introduced electroshock therapy (EST), but it later became known as ECT. In 1940, the first documented treatment of ECT was administered in the United States. An American psychiatrist, Abram E. Bennett, suggested the use of spinal anesthetics and the use of the muscle relaxant curare to reduce the incidence of fractures. In 1951, succinylcholine (Anectine) became the muscle relaxant of choice during ECT.

Between 1960 and 1970, during the advent of more effective neuroleptics, deinstitutionalization of the

mentally ill, and complaints of ECT misuse, the use of ECT declined. Complaints about ECT misuse resulted in the development of ECT task forces by the Commissioner of Mental Health in Massachusetts, the American Psychiatric Association (APA), and the International Psychiatric Association. Between 1985 and 1990, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the APA combined efforts to develop guidelines for patient selection and treatment. Although the Surgeon General released a report on mental health favoring the use of ECT in 1999, some well-intentioned activists who received ECT inappropriately suffered side effects that their doctors did not explain, or who were told that the effects of ECT were always permanent, attacked the treatment itself when the doctor who delivered the treatment was at fault. As a result of such complaints, the New Freedom Commission Report released in 2003 cited the need for mental health care reform in the United States. In 2004, the World Health Organization and Mind Freedom cited ECT as a violation of the rights of mental health clients.

mentally ill, and complaints of ECT misuse, the use of ECT declined. Complaints about ECT misuse resulted in the development of ECT task forces by the Commissioner of Mental Health in Massachusetts, the American Psychiatric Association (APA), and the International Psychiatric Association. Between 1985 and 1990, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the APA combined efforts to develop guidelines for patient selection and treatment. Although the Surgeon General released a report on mental health favoring the use of ECT in 1999, some well-intentioned activists who received ECT inappropriately suffered side effects that their doctors did not explain, or who were told that the effects of ECT were always permanent, attacked the treatment itself when the doctor who delivered the treatment was at fault. As a result of such complaints, the New Freedom Commission Report released in 2003 cited the need for mental health care reform in the United States. In 2004, the World Health Organization and Mind Freedom cited ECT as a violation of the rights of mental health clients.

These allegations have been countered by the publication of educational articles such as Clinical Science Versus Controversial Perceptions and the National Institutes of Health Consensus Statement on ECT. Although the National Association of the Mentally Ill (NAMI) does not endorse particular forms of treatment, it believes that informed individuals with neurobiologic disorders have the right to receive NIMH-approved treatments such as ECT from properly trained practitioners. NAMI opposes actions intended to limit this right (Papolos & Devanand, 2005).

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) uses electric currents to induce convulsive seizures in neurons in the entire brain to alleviate symptoms such as major depression, acute manic episodes, or schizophrenia. Although the exact mechanism of ECT is unclear, four main theories exist: the neurotransmitter theory (the correction of biochemical abnormalities of peptide and neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine produce effects similar to that of tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors); neuroendocrine theory (a release of hormones by the hypothalamus or pituitary produce antidepressant effects); anticonvulsant theory (the treatment itself minimizes or eliminates symptoms); and the frontal lobe theory (ECT minimizes or eliminates symptoms of mood or behavioral disorders that originate in the frontal lobe) (Hall & Bensing, 2005; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

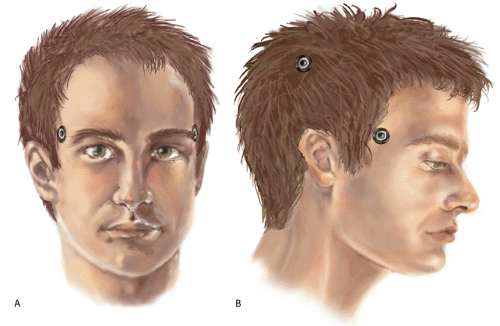

With ECT, electrodes are applied to the client’s scalp. Two types of electrode placements, bitemporal or bilateral (BL; one electrode placed on each temporal area) and right unilateral nondominant temporal (RUL; two electrodes placed on the right temporal area), are commonly used during the procedure (Figure 17-1). The left hemisphere is dominant in most persons; therefore, unilateral electrode placement is almost always over the right hemisphere. If a person exhibits right-hemisphere dominance, the polarity of electrode stimulation should be alternated during successive treatments. RUL placement has been described as more advantageous than BL placement because the negative effects on the client’s cognition and memory after treatment are lessened. However, clinical efficacy is lower, with at least a 15% greater failure rate compared with BL placement (Fink, 1999; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

A third type of placement, bifrontal (BF), in which the electrodes are placed on the forehead immediately above each eye, has been studied recently. Ongoing studies of BF placement find equal efficacy to BL placement. BF may be a useful alternative to BL placement (Fink, 1999; Fink, Abrams, Bailine, & Jaffe, 1996). Electronarcosis is a type of ECT that produces a sleep-like state without the presence of convulsions. Anesthetics and muscle relaxants are used to prohibit the development of convulsions during electrostimulation.

Indications for Use

Initially, ECT was used to treat clients with depression, schizophrenia, or the depressive phase of bipolar disorder, and clients at risk for suicide. Such use has been broadened to include clients who exhibit therapy-resistant depression, delusional depression, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), acute schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, intractable mania, catatonia, pseudodementia, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Individuals who cannot take antidepressants because of health problems or who are intent on suicide and who would not wait 3 weeks for an antidepressant to work, would be good candidates for ECT. In addition, clients who were previously treated with ECT and responded well to the procedure often elect to continue with ECT

during periods of exacerbations of clinical symptoms. Approximately 100,000 Americans elect to undergo ECT treatments each year. The effectiveness of ECT for the short-term benefit of movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, remains uncertain. ECT is not effective in somatization disorders (unless accompanied by depression), personality disorders, and anxiety disorders other than OCD (Crowe, 2005; Sadock & Sadock, 2003; MayoClinic.com, 2006).

during periods of exacerbations of clinical symptoms. Approximately 100,000 Americans elect to undergo ECT treatments each year. The effectiveness of ECT for the short-term benefit of movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, remains uncertain. ECT is not effective in somatization disorders (unless accompanied by depression), personality disorders, and anxiety disorders other than OCD (Crowe, 2005; Sadock & Sadock, 2003; MayoClinic.com, 2006).

ECT, initially used to treat adults, has been proven effective in the treatment of special populations, such as pregnant women who are unable to take psychotropic medication; children or adolescents who are depressed, are delusional, or exhibit manic episodes of bipolar disorder; elderly clients with severe depression; and persons with mental retardation who have an underlying mental health condition such as depression, mania, psychosis, or catatonia (DeMott, 1999; Fink & Foley, 1999; Sherman, 1999). Box 17-1 lists indications for ECT in children and adolescents.

Conditions Associated With Increased Risk During ECT

Several contraindications to ECT were cited when it was first introduced in 1938. At that time, the mortality rate was listed as one death per 1,000 procedures. Although serious consideration is still given regarding the use of ECT in the presence of medical conditions such as cardiac disease, expected benefits are weighed against possible risks and the likelihood of morbidity or mortality.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree