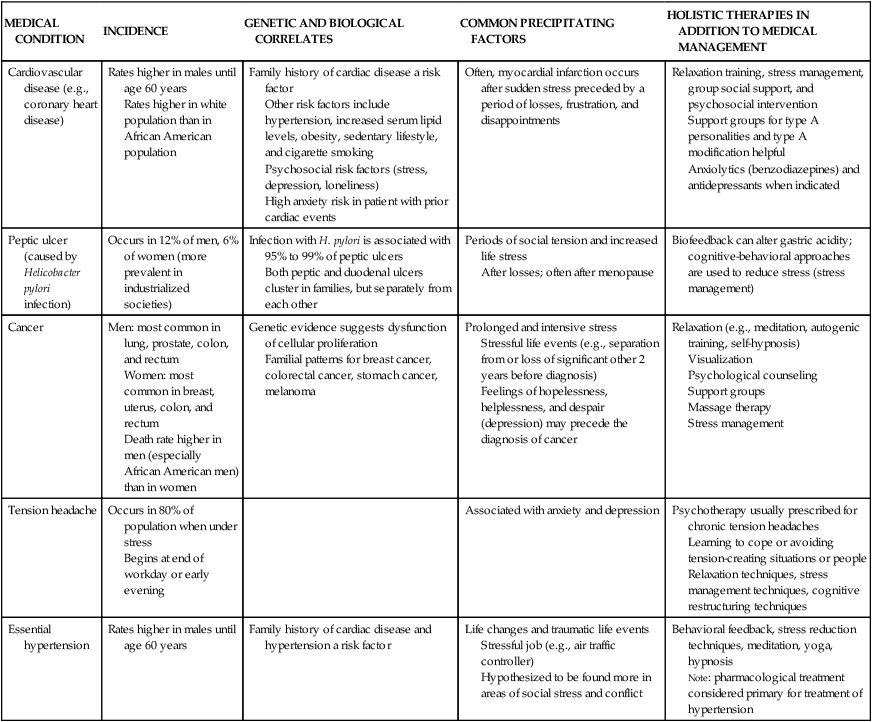

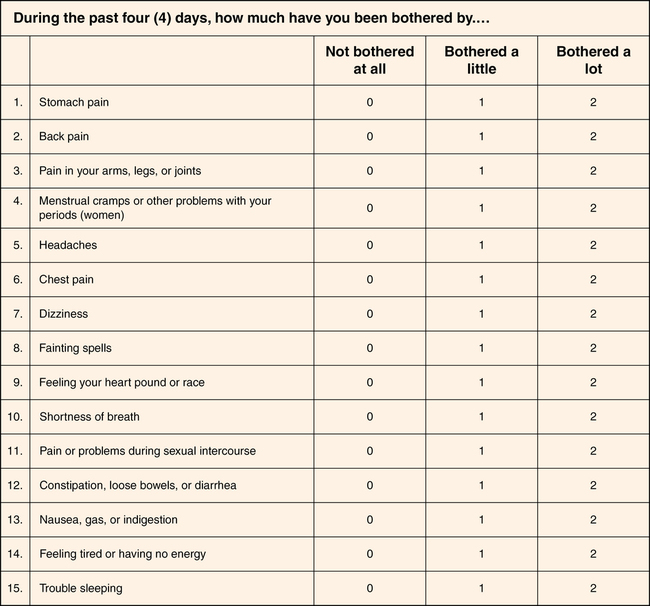

CHAPTER 17 1. Describe clinical manifestations of each of the somatic symptom disorders. 2. Discuss biological, psychological, behavioral, cognitive, environmental, and cultural factors influencing the onset and course of the somatic symptom disorders. 3. Analyze the impact of childhood trauma on adult somatic preoccupation. 4. Apply the nursing process to individuals with somatic symptom disorders. 5. Evaluate the importance of a assessing the patient”s coping skills and strengths. 6. Describe five psychosocial interventions for the care of the patient who has a somatic symptom disorder. 7. Identify the role of the advanced practice psychiatric nurse in the primary care setting. 8. Discuss the problem of factitious disorders and their implications for care. 9. Define malingering as a distinct but related problem with which health care providers are faced. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Soma is the Greek word for “body,” and somatization is the expression of psychological stress through physical symptoms. Instead of feeling anxiety, depression, or irritability, some individuals experience pain, paralysis, unexplained skin rashes, and other symptoms (Webb, 2010). Somatization disorders have been around for centuries and have disrupted countless lives; our understanding of the complexity of these disorders has only just begun (Hale & Reck, 2010). These disorders baffle both patients and health care providers. Patients worry that their problems are all in their heads and then worry that they will actually die (Dickson et al., 2009). According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), the somatic disorders include the following: • Illness anxiety disorder (previously hypochondriasis) • Conversion disorder (functional neurological disorder) • Psychological factors affecting medical condition The predominance of women with somatization is significant. It has been proposed that women are more aware of their bodily sensations, have different health-seeking behaviors when faced with physical and psychological distress, and use more health care services than men (So, 2008). In particular, young women, aged 16 to 25, are more likely to receive a somatic diagnosis than men or older individuals (Huang & McCarron, 2011). There may be a high level of medical care utilization, which rarely alleviates the patient’s concerns. Included in the most common symptoms for visits to primary care providers are chest pain, fatigue, dizziness, headache, swelling, back pain, shortness of breath, insomnia, abdominal pain, and numbness. They account for 40% of all visits to primary care providers; however, a biological cause for these symptoms is identified in only 26% of patients (Edwards et al., 2010). Health-related quality of life is frequently severely impaired, and patients appraise their bodily symptoms as unduly threatening, harmful, or troublesome, often fearing the worst about their health. Some patients feel that their medical assessment and treatment have been inadequate. When the health care provider is unable to provide a clear diagnosis for discomfort, patients can feel discounted and misunderstood. These patients tend to be devalued, stigmatized, and told that the problem is only in their heads (Noyes et al., 2010). Likewise, health care workers experience frustration in providing care for people who are not organically ill. Providers tend to use less patient-centered communication in comparison to patients with straightforward symptoms, even though somatic symptom visits are longer (Huang & McCarron, 2011). A “difficult” patient may receive a somatic diagnosis more readily than a “pleasant” patient, which could contribute to an inadequate workup. Studies show that the strongest predictor of misdiagnosing somatic disorders is the primary care provider’s dissatisfaction with the clinical encounter (Huang & McCarron, 2011). Previously known as hypochondriasis, illness anxiety disorder results in the misinterpretation of physical sensations as evidence of a serious illness. Illness anxiety can be quite obsessive as thoughts about illness may be intrusive and hard to dismiss even when the patients realize their fears are unrealistic (MacDonald, 2011). People experience extreme worry and fear about the possibility of having a disease. Even normal bodily changes, such as a change in heart rate or abdominal cramps, can be seen as red flags for serious illness. In response to these symptoms, primary care providers may suggest a consultation with a mental health professional, but the suggestion is typically refused. The course of the illness is chronic and relapsing, with symptoms becoming amplified during times of increased stress (Braun et al., 2010). Depression may play a role. Consider the case of a 72-year-old woman with illness anxiety who was treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), a treatment most often used for depression. After one session her somatic complaints stopped abruptly. This patient’s success with ECT may indicate that depressive symptoms may have been the catalyst for her symptoms, leading to the diagnosis of illness anxiety (Dols et al., 2012) Overall, the illness anxiety patient uses about 41% to 78% more health care services per year, excluding laboratory tests and x-rays prescribed in primary care, than patients with well-defined medical conditions (Fink, 2010). As illness anxiety is so prevalent, it is important that clinicians achieve basic skills in treating and identifying this disorder. If patient health concerns are addressed at an early stage, repeated consultations, multiple trials of medications, and medical examinations may be prevented (Fink, 2010). Frequent exposure to media messages reminding us to seek regular medical screenings may also contribute to fears about health (MacDonald, 2011). Studies show a relationship between exposure to breast cancer coverage in television programs to heightened fear of breast cancer (Lemal & den Bulck, 2009). Conversion disorder (also known as functional neurological disorder) manifests itself as neurological symptoms in the absence of a neurological diagnosis (Feinstein, 2011). Conversion disorder is marked by the presence of deficits in voluntary motor or sensory functions, including paralysis, blindness, movement disorder, gait disorder, numbness, paresthesia (tingling or burning sensations), loss of vision or hearing, or episodes resembling epilepsy. Conversion disorder is a clinical problem that requires the application of multiple perspectives—biological, psychological, and social—to fully understand the symptoms of individual patients. Patients with conversion disorder symptoms may be found to have “no neurological disorder” by the neurologist and “no psychiatric disorder” by the psychiatrist (Stone et al., 2010). Conversion disorder is attributed to channeling of emotional conflicts or stressors into physical symptoms; however, some MRI studies suggest that patients with conversion disorder have an abnormal pattern of cerebral activation (Feinstein, 2011). Many patients show a lack of emotional concern about the symptoms (la belle indifference) although others are quite distressed. Imagine someone casually discussing sudden blindness. Care providers should assume there is an organic cause to the symptoms until physical pathology has been ruled out. Patients truly believe in the presence of the symptoms; they are not fabricated or under voluntary control. Childhood physical or sexual abuse is common in patients with conversion disorder, and comorbid psychiatric conditions include depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, other somatic disorders, and personality disorders. There are also cases in which a comorbid medical or neurological condition exists, and the conversion disorder is an exaggeration of the original problem (Nicholson et al, 2011). Both the medical and mental health communities recognize the interrelationships between psychiatric and medical comorbidities. Psychological factors may present a risk for medical disease, or they may magnify and/or adversely affect a medical condition. Studies in recent years have contributed to the growing body of evidence for links between mental disorders and cardiovascular disease; in particular, major depressive disorder is now seen as a risk factor in the occurrence of coronary heart disease (Charlson et al., 2011). Also, a link between a history of depression and cancer incidence has been postulated since the time of the ancient Greeks, with statistical evidence reported as early as 1893. A recent study on depression as a risk factor for the incidence of cancer, conducted between 1981 and 2005, showed a significant relationship between history of depression and risk of overall cancer (Gross et al., 2010) Stress is certainly a psychological factor that can affect the disease process. Hans Selye (1956) was the first to introduce the concept of stress into the fields of medicine and physiology. Stress can lead to changes in physical and mental health in many ways. Cannon’s identification of the fight-or-flight response (1914) and Selye’s description of the general adaptation syndrome provided insight into the biological and molecular reactions to stressors in the sympathetic nervous system, the pituitary-adrenocortical axis, and the immune system. Extensive studies have left little doubt that psychosocial stress can affect the course and severity of illness (Table 17-1). TABLE 17-1 COMMON MEDICAL CONDITIONS NEGATIVELY AFFECTED BY STRESS Chronic stressors cause components of the immune system to be affected in detrimental ways. Research in the field of psychoneuroimmunology has provided insights into the relationship between psychological and physiological health in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other diseases (Temoshok et al., 2008). This research explains the negative impact of perceived stress on HIV disease progression, primarily as a function of immunosuppression mediated by elevated cortisol. Being able to reduce the stress response within this patient population is important because we can potentially positively affect not only the quality of life but also the illness trajectory of persons living with HIV. A variety of other medical disorders have been studied with regard to the effects of stress on the course of the illness. In fact, anyone experiencing a serious medical condition needs a variety of supports and may benefit from learning new coping skills. Somatizations are likely to be a complex biopsychosocial phenomenon, with many factors influencing the onset and course of the illness. A link between somatization and traumatic experiences is frequently reported (Aragona et al., 2010). Studies have also shown that patients with somatic disorders are more sensitive to negativity, less resilient in response to stress, and more prone to catastrophic thinking and negative interpretation to life events (Miller, 2009). There is increasing evidence that the behavior and mental health of primary caregivers and close family members play an important role in the development of somatization (Schulte & Petermann, 2011). In early development, stress has been implicated as a triggering factor, most often stemming from parents and the pressure to perform. Somatization is often the “tip of the iceberg” that calls for attention to a psychiatric disorder necessitating mental health treatment. Unfortunately, many untreated children risk continuous somatization as adults (Silber, 2011). Psychoanalytic theorists believe that psychogenic complaints of pain, illness, or loss of physical function are related to repression of a conflict and/or unwelcome experiences (usually of an aggressive or sexual nature), and that transformation of anxiety into a physical symptom is symbolically related to the conflict (Nicholson et al., 2011). For example, in conversion disorder, conversion symptoms allow a forbidden wish or urge to be partly expressed but sufficiently disguised so that the individual does not have to face the unacceptable wish. The symptoms also permit the individual to communicate a need for special treatment or consideration from others. Since the late 19th century, psychoanalytic theory has dominated medical thinking about conversion disorder. Neither psychiatry nor neurology has successfully tackled the challenge by Freud a century ago regarding what causes this “mysterious leap from mind to body” (Stone et al., 2010) We know that adverse childhood events result in lifelong problems, including somatization disorders. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE) (Fuller-Thomson et al., 2011) surveyed more than 16,000 adults and discovered that childhood trauma exposure accounted for negative outcomes across a variety of diagnoses in later life, including multiple somatic symptoms diabetes, heart disease, cancer, gastrointestinal conditions, and immune functioning. Childhood maltreatment has been associated with elevated levels of C-reactive protein, a biomarker of inflammation that may play a role in autoimmune diseases in adults 20 years later (Dube et al., 2009). The Evidence-Based Practice Box provides more information on the connection between childhood trauma and subsequent somatization. The type and frequency of somatic symptoms vary across cultures. Burning hands and feet or the sensation of worms in the head or ants under the skin is more common in Africa and southern Asia than in North America. Alteration of consciousness with falling is a symptom commonly associated with culture-specific religious and healing rituals. Somatization disorder, which is rarely seen in men in the United States, is often reported in Greek and Puerto Rican men, which suggests that cultural customs may permit these men to use somatization as an acceptable approach to dealing with life stress. Somatization related to posttraumatic stress and depression was the most prevalent psychiatric symptom in North Korean defectors to South Korea (Kim et al., 2011) West Indians (Caribbean) attribute somatic symptoms to chronic overwork and the irregularity of daily living, citing symptoms such as dizziness, fatigue, joint pain, and muscle tension. Patients from Korea may explain some distress as “hwa-byung,” a syndrome of both somatic and depressive symptoms, commonly attributed to suppressed anger or rage (Edwards et al., 2010). In contemporary Western culture, there has been unprecedented growth and comfort in the past few decades; however, levels of health have not increased. Core values such as materialism, consumerism, and individualism may be damaging to individuals’ sense of well-being and health, including a high incidence of somatization. A study of children reared in the United States from 1970 through the 1990s shows these adults as tolerant, confident, open-minded and ambitious, but also cynical, depressed, lonely, and anxious, characteristics that contribute to the development of somatic symptomatology (Carlisle & Hanlon, 2007). Abraham Maslow in his “hierarchy of needs” theorizes that humans are inclined to shift attention to higher-level needs (social, intellectual, spiritual) once lower-level needs of food, shelter, and clothing are attained; however, Western consumer culture has become extremely adept at persuading people to remain fixated upon materialism, resisting movement to higher-level needs such as love, belonging, and respect for others (Schumaker, 2007). This current consumer culture of individualism with decreased interest in family/group needs negatively impacts supportive development of communities, socialization, and overall mental and physical health, including somatic responses of individuals. In addition, somatization among the immigrant population in the United States in primary care is significantly related to traumatic events (see Considering Culture box). Immigrants frequently experience multiple traumatic events, both intentional and unintentional, in premigration as well as postmigration life. A study of asylum seekers reported 79% had experienced a traumatic event such as witnessing killings, being assaulted, or suffering torture and captivity. It is important for primary care providers evaluating immigrants to be aware of the possible link between somatization symptoms reported by the patient and undisclosed traumatic experiences (Aragona et al., 2010). Patients across cultures with somatic symptoms often offer clues about their underlying concerns and want more emotional support from their health care provider in comparison to other patients, and they are most satisfied with their care when their health care provider shares their understanding of the presenting problems and treatment options (Edwards et al., 2010). A useful assessment tool to understand the degree of somatization is the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ), a somatic symptom severity scale for the purpose of diagnosis (Figure 17-1). The questionnaire inquires about 15 somatic symptoms that account for more than 90% of physical complaints reported in the primary care setting by asking patients to rate severity of symptoms during the previous 4 days on a 3-point scale. Those symptoms are stomach pain, back pain, headache, chest pain, dizziness, fainting, palpitations, shortness of breath, bowel complaints, nausea, fatigue, sleep problems, pain in joints/limbs, menstrual pain, and problems during sexual intercourse (Korber et al., 2011). • Someone who can share his or her concerns and who cares for him or her • Friends and supports in the community and/or involvement in individual therapy • Any coexisting conditions that could negatively affect healthy adaptation or ability to heal (e.g., anxiety, depression, personality disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or substance abuse and other compulsive behaviors) • Risky health behaviors (e.g., sedentary lifestyle, smoking, engaging in unsafe sex practices, and/or abusing alcohol or drugs) • A cultural view of health and illness that helps or impedes the process of seeking adequate care (e.g., resilience, communication skills, assertiveness)

Somatic symptom disorders

![]()

Clinical picture

Somatic symptom disorder

Illness anxiety disorder

Conversion disorder

Psychological factors affecting medical condition

MEDICAL CONDITION

INCIDENCE

GENETIC AND BIOLOGICAL CORRELATES

COMMON PRECIPITATING FACTORS

HOLISTIC THERAPIES IN ADDITION TO MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Cardiovascular disease (e.g., coronary heart disease)

Rates higher in males until age 60 years

Rates higher in white population than in African American population

Family history of cardiac disease a risk factor

Other risk factors include hypertension, increased serum lipid levels, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and cigarette smoking

Psychosocial risk factors (stress, depression, loneliness)

High anxiety risk in patient with prior cardiac events

Often, myocardial infarction occurs after sudden stress preceded by a period of losses, frustration, and disappointments

Relaxation training, stress management, group social support, and psychosocial intervention

Support groups for type A personalities and type A modification helpful

Anxiolytics (benzodiazepines) and antidepressants when indicated

Peptic ulcer (caused by Helicobacter pylori infection)

Occurs in 12% of men, 6% of women (more prevalent in industrialized societies)

Infection with H. pylori is associated with 95% to 99% of peptic ulcers

Both peptic and duodenal ulcers cluster in families, but separately from each other

Periods of social tension and increased life stress

After losses; often after menopause

Biofeedback can alter gastric acidity; cognitive-behavioral approaches are used to reduce stress (stress management)

Cancer

Men: most common in lung, prostate, colon, and rectum

Women: most common in breast, uterus, colon, and rectum

Death rate higher in men (especially African American men) than in women

Genetic evidence suggests dysfunction of cellular proliferation

Familial patterns for breast cancer, colorectal cancer, stomach cancer, melanoma

Prolonged and intensive stress

Stressful life events (e.g., separation from or loss of significant other 2 years before diagnosis)

Feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and despair (depression) may precede the diagnosis of cancer

Relaxation (e.g., meditation, autogenic training, self-hypnosis)

Visualization

Psychological counseling

Support groups

Massage therapy

Stress management

Tension headache

Occurs in 80% of population when under stress

Begins at end of workday or early evening

Associated with anxiety and depression

Psychotherapy usually prescribed for chronic tension headaches

Learning to cope or avoiding tension-creating situations or people

Relaxation techniques, stress management techniques, cognitive restructuring techniques

Essential hypertension

Rates higher in males until age 60 years

Family history of cardiac disease and hypertension a risk factor

Life changes and traumatic life events

Stressful job (e.g., air traffic controller)

Hypothesized to be found more in areas of social stress and conflict

Behavioral feedback, stress reduction techniques, meditation, yoga, hypnosis

Note: pharmacological treatment considered primary for treatment of hypertension

Etiology

Psychological factors

Psychodynamic theories

Environmental factors

Cultural considerations

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

Psychosocial factors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Somatic symptom disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access