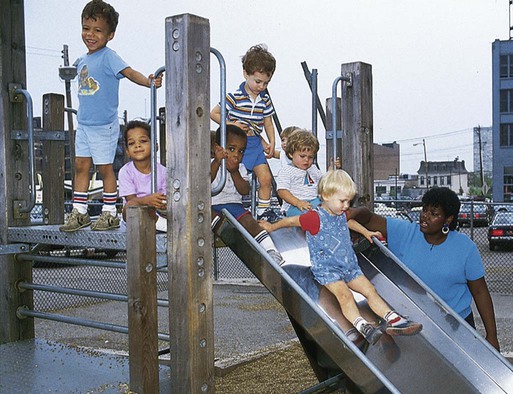

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Define culture, cultural competence, ethnocentrism, and cultural relativity. • Describe the subcultural influences on child development. • Discuss the population of minority children in the United States. • Identify the impact of culture on health. • Identify the impact socioeconomic influences have on health. • Identify areas of potential conflict of values and customs for a nurse interacting with different cultural and ethnic groups. http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/essentials Promoting the health of children requires a nurse to understand social, cultural, and religious influences on children and their families. This in turn depends on a purposeful awareness of the child’s sociocultural context and also of oneself. The purpose of this chapter is to share with nursing students the significance of providing nursing care with a sense of cultural humility as a way to provide optimal care to all children and their families and to further understand the intersection of social, religious, and cultural forces that affect the health of children, their families, and their communities. Why is this important? The U.S. population is constantly evolving; patients experience negative health outcomes when social, cultural, and religious factors are not considered as influencing their health care; families may incorporate other health systems such as Eastern medicine or traditional healing into their lives; and it is required by legislative, regulatory, and credentialing bodies (Tervalon, 2003). Educating health care providers is one way to reduce disparities in health care. Cultural humility is a “commitment and active engagement in a lifelong process that individuals enter into on an ongoing basis with patients, communities, colleagues, and themselves” (Tervalon and Murray-Garcia, 1998, p. 118). It requires that health care providers participate in a continual process of self-reflection and self-critique that recognizes the power of the health care provider role, that views the patient and family as full members of the health care team, and that does not end after reading one chapter or attending one course but is an evolving aspect of being a health care provider. “Cultural competency is not an abdominal exam” (Kumagai and Lypson, 2009, p. 783). It is not a static endpoint to be checked off the list but an ongoing process that promotes deeper thinking and knowledge of oneself, others, and the world (Kumagai and Lypson, 2009). Approaching nursing care from a position of cultural humility is important considering the ever-changing population. A sample of the demographic profile of the U.S. 2010 census includes 72.4% non-Hispanic white; 16.3% Hispanic/Latino; 12.6% Black/African American; and 3.6% Asian or American Indian/Alaskan Native (Humes, Jones, and Ramirez, 2011). Interestingly, the 2010 census data reveal that more than half of the population growth in the United States from 2000 to 2010 was attributable to increases in the Hispanic/Latino population. In addition, the population that defines their ethnicity as Asian grew faster than any other group, up 43% from the 2000 census. Children and adolescents 0 to 18 years of age comprised 24.3% of the U.S. population. The demographic profile includes white/non-Hispanic, 55.3%; Black/African American, 15.1%; Asian, 4.3%; Hispanic (any race), 22.5%; and all other, 4.7%. Traditionally, children younger than 5 years of age are highly underreported. This is problematic because the number and demographics of children determines the demand for schools, health care, and other services needed to meet the needs of families. It is also important to understand nursing’s contribution to culturally congruent care. A holistic view of care was first described by Madeleine Leininger, the recognized founder of transcultural nursing, in her culture care diversity and universality theory (Leininger, 2001; Munoz and Luckmann, 2005). The theory provides an intellectual framework and a research methodology for providing culturally congruent patient care. Nurses must remain aware that every family, child, and health care provider comes to a clinical encounter with a cultural lens through which they see and interpret the world. Culture is a rich context through which people view and respond to their world (see Cultural Considerations box). It also provides the lens through which all facets of human behavior can be interpreted (Spector, 2009). Culture is composed of individuals who share a set of values, beliefs, practices (e.g., language, dress, diet, health care), social relationships, laws, politics, economics, and norms of behavior that are learned, integrative, social, and satisfying. Culture is an ingrained orientation to life that serves as a frame of reference for individual perception and judgment. Culture is, essentially, the way of life of a group of people that incorporates experiences of the past, influences thought and action in the present, and transmits these traditions to future group members. Families pass their culture on to children, and the children perceive the world through this cultural lens. Culture adapts to the ever-changing world as group members abandon, modify, or assume new patterns of living and behavior to meet the group’s needs. Cultures and subcultures contribute to the uniqueness of child members in such a subtle way and at such an early age that children grow up to think that their beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices are the “correct” or “normal” ones. By age 5 years, children can identify persons who belong to their cultural background. During later primary years, children can identify those from different cultures (Trawick-Smith, 2006). A set of values learned in childhood is likely to characterize children’s attitudes and behavior for life, influencing their long-range goals and their short-range, impulsive inclinations. Thus, every ongoing society socializes each succeeding generation to its cultural heritage. The manner and sequence of the growth and development phenomenon are universal and fundamental features of all children; however, children’s varied behavioral responses to similar events are often determined by their culture. Culture plays a critical role in the parenting behaviors that facilitate children’s development (Melendez, 2005). Children acquire the skills, knowledge, beliefs, and values important to their own family and culture. Cultural backgrounds can influence the pace of acquisition of cognitive and motor skills as well as the child’s social and emotional development (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Context provides perspective for nursing care. The health and well-being of the child in the North American family is influenced by two distinct contexts: the context of family and the context of culture. Therefore, understanding these layers of influence on pediatric health is integral to developing a family-centered and culturally competent nursing practice (Thibodeaux and Deatrick, 2007). America’s orientation toward homogenization—“the great melting pot”—is changing because of its increasingly diverse population. Culture influences a child’s sense of self-esteem (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Some cultures are more collective in thought and action. A child from a collective culture will hold an inclusive view of him- or herself. Self-evaluation is related to the accomplishments or competencies of the entire family or community. School experiences that focus on personal achievement may promote positive self-esteem in some children but not in others who are more dependent on the success of a whole family or peer group. Their sense of control may not come from individual self-reliance but rather from a feeling of worth in their family or community (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Families and culture also influence the criteria children use to evaluate their own abilities. Additionally, cultures vary in whether they instill an internal locus of control (a belief in the ability to regulate one’s own life). Effects on self-esteem are minimal if these beliefs are directed by parents and are in accordance with cultural customs (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Ethnic pride can help children to maintain a positive self-image and counteract the effects of prejudice, which can have a negative impact on emotional health (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Cultural shock is characterized by the inability to respond to or function within a new or strange situation. It can occur when the values and beliefs of a new cultural setting are radically different from those of the person’s native culture (Munoz and Luckmann, 2005). This state of shock or uneasiness can happen to a patient in a hospital or to a nurse caring for patients with different cultural backgrounds. Immigrants to a new country and persons from a subcultural group experience the same cultural shock when they must adjust to the ways of an unfamiliar subgroup or setting. Nurses are challenged to overcome cultural shock and develop cultural sensitivity, an awareness of cultural similarities and differences. Doing so helps the nurse practice culturally competent care. This requires changing the way people think about, understand, and interact within the world around them (see Critical Thinking Case Study). The development of cultural competence is an ongoing, interactive process that involves six elements (Dunn, 2002): 1. Working on changing one’s world view by examining one’s own values and behaviors and working to reject racism and institutions that support it 2. Becoming familiar with core cultural issues by recognizing these issues and exploring them with patients 3. Becoming knowledgeable about the cultural groups one works with while learning about each individual patient’s unique history 4. Becoming familiar with core cultural issues related to health and illness and communicating in a way that encourages patients to explain what an illness means to them 5. Developing a relationship of trust with patients and creating a welcoming atmosphere in the health care setting 6. Negotiating for mutually acceptable and understandable interventions of care When minority groups immigrate from another country, a certain degree of cultural and ethnic blending occurs through the involuntary process of acculturation, gradual changes produced in a culture by the influence of another culture that cause one or both cultures to be more similar to each other. However, the changes occur to various degrees in different families and groups. Many groups continue to identify with their traditional heritage while adapting to the ill-defined concept of the “American way.” Acculturation may be referred to as assimilation, which is the process of developing a new cultural identity (Spector, 2009). Ethnicity is the classification of or affiliation with any of the basic groups or divisions of humankind or any heterogeneous population differentiated by customs, characteristics, language, or similar distinguishing factors. Ethnic differences extend to many areas and include such manifestations as family structure, language, food preferences, moral codes, and expression of emotion. Some standards of behavior (e.g., the traditional role of the father) result from the cultural heritage of the specific ethnic group. Others reflect the interaction between subcultures, most notably between members of the majority culture and a minority subculture. The term ethnic has aroused strong negative feelings, and the general population often rejects this term (Spector, 2009). In the United States, the cross-cultural lines are becoming blurred as subcultures are assimilated and blended into the larger culture (Fig. 4-1). Although ethnic differences in childrearing are probably diminishing, they remain important. It is particularly difficult for persons to attempt to maintain an identity within a subculture while living and conforming to the requirements of the larger culture. Ethnocentrism is the emotional attitude that one’s own ethnic group is superior to others; that one’s values, beliefs, and perceptions are the correct ones; and that the group’s ways of living and behaving are the best way (Spector, 2009). Ethnic stereotyping or labeling stems from ethnocentric views. Ethnocentrism implies that all other groups are inferior and that their ways are not in the best interests of the group. It is a common attitude among a dominant ethnic group and strongly influences a person’s ability to evaluate objectively the beliefs and behaviors of others. Nurses must overcome the natural tendency to have ethnocentric attitudes when caring for people from different cultures. Culturally competent nurses have empathy for others, maintain an openness to feeling what others feel, and remain curious and willing to ask questions to gain a better understanding. In addition, nurses have a basic respect for themselves and others and acknowledge the intrinsic value of all humans. The United States has more racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups than any other country. Ethnic minority groups are becoming increasingly important because these groups are producing children at a faster rate than the majority white population. Consequently, the minority population is increasing. The rapidly emerging U.S. minority population will present special needs and require resources beyond what is currently available (Murdock, 2005). The U.S. 2010 census revealed more than 300 million people in the United States. The Hispanic population included 16.3% of the total population (Humes, Jones, and Ramirez, 2011). Currently, Hispanics are the fastest growing minority in the United States and have many health needs that are not being met (Murdock, 2005). In 2050, almost 30% of the U.S. population is expected to be Hispanic (Murdock, 2005). Historically, schools have participated in devaluing Native American languages, cultures, and traditional ways of learning and knowing. Unfortunately, Native American children have been deficient in their preparation for school (Beaulieu, 2000). Also, children of Native American nations have been at risk for low achievement, overrepresentation in special education, and dropping out (Demmert, 2001). Many regional dialects and variations in language usage must be considered when communicating with persons from these groups. English words that sound like words in a foreign language can cause considerable misunderstanding. Children of some cultural groups fare less well in school. They come from underrepresented groups, including African-American, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and Native American children (Trawick-Smith, 2006). These cultural variations can be attributed to high rates of poverty, different cognitive styles, ineffective schools, and parents’ views of schools as oppressive to cultural and traditional values (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Four categories of external assets that youth receive from the community are (Search Institute, 2007): 1. Support—Young people need to feel support, care, and love from their families, neighbors, and others. They also need organizations and institutions that offer positive, supportive environments. 2. Empowerment—Young people need to feel valued by their community and be able to contribute to others. They need to feel safe and secure. 3. Boundaries and expectations—Young people need to know what is expected of them and what activities and behaviors are within the community boundaries and what are outside of them. 4. Constructive use of time—Young people need opportunities for growth through constructive, enriching opportunities and through quality time at home. Internal assets must also be nurtured in the community’s young members. These internal qualities guide choices and create a sense of centeredness, purpose, and focus. The four categories of internal assets are (Search Institute, 2007): 1. Commitment to learning—Young people need to develop a commitment to education and lifelong learning. 2. Positive values—Youth need to have a strong sense of values that direct their choices. 3. Social competencies—Young people need competencies that help them make positive choices and build relationships. 4. Positive identity—Young people need a sense of their own power, purpose, worth, and promise. Peer groups also have an impact on the socialization of children (Fig. 4-2). Peer relationships become increasingly important and influential as children proceed through school. In school, children have what can be regarded as a culture of their own. This is even more apparent in unsupervised playgroups because the culture in school is partly produced by adults. The kind of socialization provided by the peer group depends on the subculture that develops from its members’ background, interests, and capabilities. Some groups support school achievement, others focus on athletic prowess, and still others are decidedly against educative goals. Scholastic achievement is strongly related to the peer group’s value system. Many conflicts between teachers and students and between parents and students can be attributed to fear of rejection by peers. What is expected from parents regarding academic achievement and what is expected from the peer culture often conflict, especially during high school. Chapter 19 discusses this in further detail. The media provide children with a means for extending their knowledge about the world in which they live and have helped narrow the differences between groups. However, many people are concerned about the enormous influence the media can have on developing children and on health promotion behaviors. Children and adolescents in the United States spend more than 6 hours per day using entertainment media (Council on Communications and Media, 2009). Increased use of entertainment media has been associated with the epidemic of obesity in children and adolescents and increased aggression in children (Council on Communications and Media, 2009; Jordan, 2004). Anticipatory guidance around media utilization is among the most important a nurse can offer to a family. Because it can influence many areas of concern, such as aggression, sex, drugs, alcohol, obesity, eating disorders, and academic achievement (Strasburger, 2010), two important questions that nurses can ask to open the dialogue are “How much entertainment screen time does your child or teen spend each day?” and “Is there a TV, Internet connection, or wireless connection in the child or teen’s bedroom?” Researchers have established links between mass media and an increase in the use of tobacco, alcohol, and violent behavior in adolescents (Council on Communications and Media, 2009; Strasburger, 2010). The images of risky behavior presented by the media may serve to establish or reinforce teenagers’ perceptions of their social environment. Also, media content may directly influence risk perception; media protagonists seldom experience the adverse consequences of their behaviors despite their grossly distorted experiences with violence, illness, or crime. Children may identify closely with people or characters portrayed in reading materials, movies, and television programs and commercials. Pediatric nurses can educate and support parents on the effects of mass media on their children through the following recommendations (Jordan, 2004): • Be aware of the content of the child’s media and amount of time spent looking at a screen. • Help young children watching television to find educational programs. • Remove television, Internet-accessible computers, and video game systems from the bedroom to decrease the amount of time spent using these activities. • Limit television viewing to 2 hours a day or less. • Watch age-appropriate programs and play age-appropriate games with children. The medium that has the most impact on children in the United States today is television; it has become one of the most significant socializing agents in the lives of young children. Its programs and commercials provide multiple sources for acquiring information, modeling behaviors, and observing value orientations. Besides producing a leveling effect on class differences in general information and vocabulary, TV exposes children to a wider variety of topics and events than they encounter in day-to-day life. Television always has time to talk to children and is a form of access to the adult world. Positive results occur only when viewing is relatively light, yet the average child in the United States older than the age of 8 years spends more time watching television or using a computer and video games (>6 hours/day) than in any other activity except sleeping (Fig. 4-3) (Council on Communications and Media, 2009). Television can offer some beneficial effects on growing children by teaching healthy ideas and habits. Shows like Sesame Street promote school readiness by teaching letters and numbers, as well as teaching children about kindness and tolerance towards people who are different than them (Strasburger, 2010). Unfortunately, there is an imbalance in the availability of healthy and unhealthy media. Most researchers have concluded, however, that protracted television viewing can have negative effects on children. Increased verbal and physical aggressiveness, reduced persistence at problem solving, greater sex-role stereotyping, and reduced creativity have been reported repeatedly. In fairness, no one has yet defined the long-term effects of other electronic factors such as stereo headphones versus conversation, computer games or drills versus active social play, or DVDs versus books. However, clearly, children in the modern electronic environment are constantly stimulated from the outside, which allows them little time to reflect and develop the inner speech that feeds brain development.

Social, Cultural, and Religious Influences on Child Health Promotion

Culture

The Child and Family in North America

Social Roles

Self-Esteem and Culture

Cultural Shock and Cultural Sensitivity

Subcultural Influences

Ethnicity

Minority-Group Membership

Socioeconomic Class

Communication Skills

Schools

Socialization

Communities

Peer Cultures

Mass Media

Television

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Social, Cultural, and Religious Influences on Child Health Promotion

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access