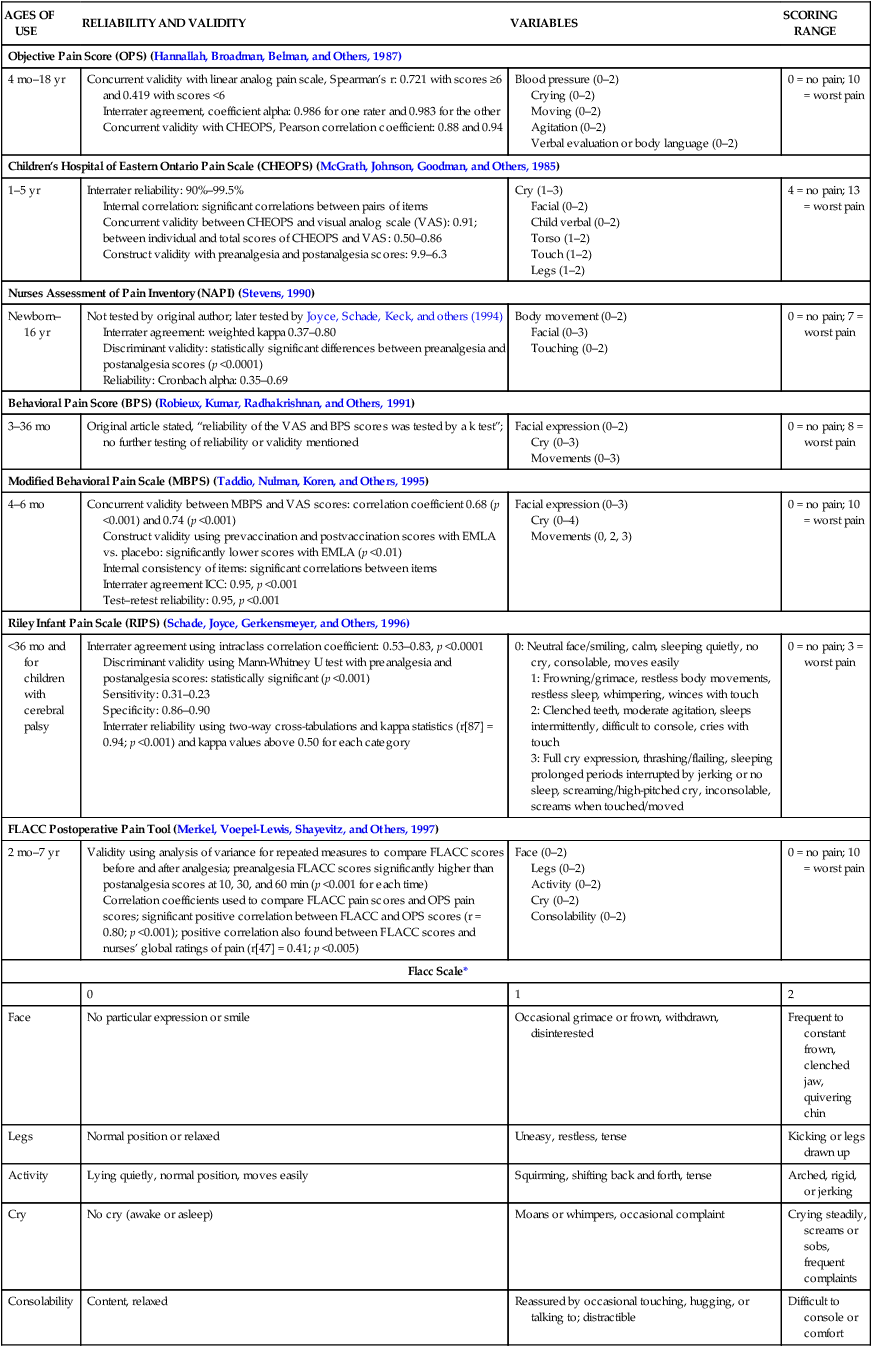

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Identify measures to assess pain in children. • List various types of pain assessment tools for use with children. • Outline essential pain management strategies to reduce pain in children. • Review common types of pain experienced by children. • Discuss evidence to support specific pain management strategies. http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/essentials Many children and adolescents continue to suffer from inadequately treated pain of all types (Perquin, Hazebroek-Kampschreur, Hunfeld, and others, 2000a, 2000b). Several research studies suggest that the undertreatment of pain in children is related to inconsistent practice in pain assessment, administration of analgesics at subtherapeutic levels, prolonged intervals in between medications (Jacob and Puntillo, 2000), and lack of systematic monitoring and evaluation of relief (Jacob, Miaskowski, Savedra, and others, 2003a, 2003b; Jacob and Mueller, 2008). Optimal pain management begins with thorough assessment, which will guide the selection of treatments. Acute pain assessment is easier to perform than complex pain that may be chronic, recurrent, or persistent. The assessment of pain needs to reflect the variations in children’s cognitive, emotional, and physical capabilities (Box 7-1). Six core domains and specific measures to assess and measure pain in children are recommended: (1) pain intensity, (2) global judgment of satisfaction with treatment, (3) symptoms and adverse events, (4) physical recovery, (5) emotional response, and (6) economic factors (McGrath, Walco, Turk, and others, 2008). These domains will be discussed as they relate to assessment of acute, chronic, and recurrent pain. Traditionally, assessment measures are defined as behavioral measures, physiologic measures, and measures of self-reports. These measures predominantly address the domain of pain intensity. The behavioral measures of pain (for infants and children younger than 4 years; Table 7-1) and self-reports of pain (for children 4 years and older; Table 7-2) have been developed, validated, and widely used. Self-report measures are not sufficiently valid for children younger than 3 years of age because many are not able to accurately self-report their pain. Distress behaviors, such as vocalization, facial expression, and body movement, have been associated with pain (Figs. 7-1 and 7-2). These behaviors are helpful in evaluating pain in infants and children with limited communication skills. However, discriminating between pain behaviors and reactions from other sources of distress, such as hunger, anxiety, or other types of discomfort, is not always easy. These factors decrease the specificity and sensitivity of behavioral measures (see Table 7-1). TABLE 7-1 SUMMARY OF SELECTED BEHAVIORAL PAIN ASSESSMENT SCALES FOR YOUNG CHILDREN *From Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, and others: The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children, Pediatr Nurs 23(3):293–297, 1997. Used with permission of Jannetti Publications, Inc., and the University of Michigan Health System. Can be reproduced for clinical and research use. TABLE 7-2 PAIN RATING SCALES FOR CHILDREN

Pain Assessment and Management in Children

Pain Assessment

Assessment of Acute Pain

Pain Intensity

AGES OF USE

RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY

VARIABLES

SCORING RANGE

Objective Pain Score (OPS) (Hannallah, Broadman, Belman, and Others, 1987)

4 mo–18 yr

Concurrent validity with linear analog pain scale, Spearman’s r: 0.721 with scores ≥6 and 0.419 with scores <6

Interrater agreement, coefficient alpha: 0.986 for one rater and 0.983 for the other

Concurrent validity with CHEOPS, Pearson correlation coefficient: 0.88 and 0.94

Blood pressure (0–2)

Crying (0–2)

Moving (0–2)

Agitation (0–2)

Verbal evaluation or body language (0–2)

0 = no pain; 10 = worst pain

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) (McGrath, Johnson, Goodman, and Others, 1985)

1–5 yr

Interrater reliability: 90%–99.5%

Internal correlation: significant correlations between pairs of items

Concurrent validity between CHEOPS and visual analog scale (VAS): 0.91; between individual and total scores of CHEOPS and VAS: 0.50–0.86

Construct validity with preanalgesia and postanalgesia scores: 9.9–6.3

Cry (1–3)

Facial (0–2)

Child verbal (0–2)

Torso (1–2)

Touch (1–2)

Legs (1–2)

4 = no pain; 13 = worst pain

Nurses Assessment of Pain Inventory (NAPI) (Stevens, 1990)

Newborn–16 yr

Not tested by original author; later tested by Joyce, Schade, Keck, and others (1994)

Interrater agreement: weighted kappa 0.37–0.80

Discriminant validity: statistically significant differences between preanalgesia and postanalgesia scores (p <0.0001)

Reliability: Cronbach alpha: 0.35–0.69

Body movement (0–2)

Facial (0–3)

Touching (0–2)

0 = no pain; 7 = worst pain

Behavioral Pain Score (BPS) (Robieux, Kumar, Radhakrishnan, and Others, 1991)

3–36 mo

Original article stated, “reliability of the VAS and BPS scores was tested by a k test”; no further testing of reliability or validity mentioned

Facial expression (0–2)

Cry (0–3)

Movements (0–3)

0 = no pain; 8 = worst pain

Modified Behavioral Pain Scale (MBPS) (Taddio, Nulman, Koren, and Others, 1995)

4–6 mo

Concurrent validity between MBPS and VAS scores: correlation coefficient 0.68 (p <0.001) and 0.74 (p <0.001)

Construct validity using prevaccination and postvaccination scores with EMLA vs. placebo: significantly lower scores with EMLA (p <0.01)

Internal consistency of items: significant correlations between items

Interrater agreement ICC: 0.95, p <0.001

Test–retest reliability: 0.95, p <0.001

Facial expression (0–3)

Cry (0–4)

Movements (0, 2, 3)

0 = no pain; 10 = worst pain

Riley Infant Pain Scale (RIPS) (Schade, Joyce, Gerkensmeyer, and Others, 1996)

<36 mo and for children with cerebral palsy

Interrater agreement using intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.53–0.83, p <0.0001

Discriminant validity using Mann-Whitney U test with preanalgesia and postanalgesia scores: statistically significant (p <0.001)

Sensitivity: 0.31–0.23

Specificity: 0.86–0.90

Interrater reliability using two-way cross-tabulations and kappa statistics (r[87] = 0.94; p <0.001) and kappa values above 0.50 for each category

0: Neutral face/smiling, calm, sleeping quietly, no cry, consolable, moves easily

1: Frowning/grimace, restless body movements, restless sleep, whimpering, winces with touch

2: Clenched teeth, moderate agitation, sleeps intermittently, difficult to console, cries with touch

3: Full cry expression, thrashing/flailing, sleeping prolonged periods interrupted by jerking or no sleep, screaming/high-pitched cry, inconsolable, screams when touched/moved

0 = no pain; 3 = worst pain

FLACC Postoperative Pain Tool (Merkel, Voepel-Lewis, Shayevitz, and Others, 1997)

2 mo–7 yr

Validity using analysis of variance for repeated measures to compare FLACC scores before and after analgesia; preanalgesia FLACC scores significantly higher than postanalgesia scores at 10, 30, and 60 min (p <0.001 for each time)

Correlation coefficients used to compare FLACC pain scores and OPS pain scores; significant positive correlation between FLACC and OPS scores (r = 0.80; p <0.001); positive correlation also found between FLACC scores and nurses’ global ratings of pain (r[47] = 0.41; p <0.005)

Face (0–2)

Legs (0–2)

Activity (0–2)

Cry (0–2)

Consolability (0–2)

0 = no pain; 10 = worst pain

Flacc Scale*

0

1

2

Face

No particular expression or smile

Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, disinterested

Frequent to constant frown, clenched jaw, quivering chin

Legs

Normal position or relaxed

Uneasy, restless, tense

Kicking or legs drawn up

Activity

Lying quietly, normal position, moves easily

Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense

Arched, rigid, or jerking

Cry

No cry (awake or asleep)

Moans or whimpers, occasional complaint

Crying steadily, screams or sobs, frequent complaints

Consolability

Content, relaxed

Reassured by occasional touching, hugging, or talking to; distractible

Difficult to console or comfort

PAIN SCALE, DESCRIPTION

INSTRUCTIONS

RECOMMENDED AGE AND COMMENTS

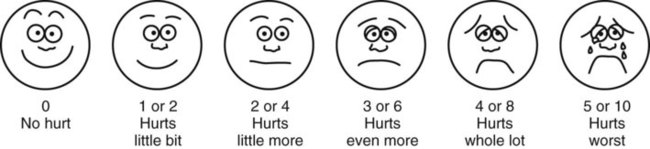

FACES Pain Rating Scale*

Consists of six cartoon faces ranging from smiling face for “no hurt” to tearful face for “hurts worst”

Original instructions:

Explain to child that each face is for a person who feels happy because there is no pain (hurt) or sad because there is some or a lot of pain. FACE 0 is very happy because there is no hurt. FACE 1 hurts just a little bit. FACE 2 hurts a little more. FACE 3 hurts even more. FACE 4 hurts a whole lot, but FACE 5 hurts as much as you can imagine, although you don’t have to be crying to feel this bad. Ask child to choose face that best describes own pain. Record number under chosen face on pain assessment record.

Brief word instructions:

Point to each face using the words to describe the pain intensity. Ask child to choose face that best describes own pain and record appropriate number.

Children as young as 3 yr

Using original instructions without affect words, such as happy or sad, or brief words resulted in same range of pain rating, probably reflecting child’s rating of pain intensity. For coding purposes, numbers 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 can be substituted for 0–5 system to accommodate 0–10 system.

The FACES provides three scales in one: facial expressions, numbers, and words.

Research supports cultural sensitivity of FACES for white, African-American, Hispanic, Thai, Chinese, and Japanese children.

Oucher (Beyer, Denyes, and Villarruel, 1992)

Consists of six photographs of a white child’s face representing “no hurt” to “biggest hurt you could ever have”; also includes vertical scale with numbers from 0 to 100; scales for African-American and Hispanic children have been developed (Villarruel and Denyes, 1991)

Numeric scale:

Point to each section of scale to explain variations in pain intensity:

“0 means no hurt.”

“This means little hurts” (pointing to lower part of scale, 1–29).

“This means middle hurts” (pointing to middle part of scale, 30–69).

“This means big hurts” (pointing to upper part of scale, 70–99).

“100 means the biggest hurt you could ever have.”Score is actual number stated by child.

Photographic scale:

Point to each photograph and explain variations in pain intensity using following language: first picture from the bottom is “no hurt,” second is “a little hurt,” third is “a little more hurt,” fourth is “even more hurt than that,” fifth is “pretty much or a lot of hurt,” and sixth is “biggest hurt you could ever have.”

Score pictures from 0 to 5, with bottom picture scored as 0.

General:

Practice using Oucher by recalling and rating previous pain experiences (e.g., falling off bike). Child points to number or photograph that describes pain intensity associated with experience. Obtain current pain score from child by asking, “How much hurt do you have right now?”

Children 3–13 yr

Use numeric scale if child can count off any two numbers or by tens (Jordan-Marsh, Yoder, Hall, and others, 1994).

Determine whether child has cognitive ability to use photographic scale; child should be able to rate six geometric shapes from largest to smallest.

Determine which ethnic version of Oucher to use. Allow child to select version of Oucher or use version that most closely matches physical characteristics of child.

NOTE: Ethnically similar scale may not be preferred by child when given choice of ethnically neutral cartoon scale (Luffy and Grove, 2003).

Poker Chip Tool (Hester, Foster, Jordan-Marsh, and Others, 1998)

Uses four red poker chips placed horizontally in front of child

Say to child: “I want to talk with you about the hurt you may be having right now.” Align chips horizontally in front of child on bedside table, clipboard, or other firm surface.

Tell child, “These are pieces of hurt.” Beginning at chip nearest child’s left side and ending at one nearest right side, point to chips and say, “This (first chip) is a little bit of hurt and this (fourth chip) is the most hurt you could ever have.” For a young child or for any child who may not fully comprehend the instructions, clarify by saying, “That means this (1) is just a little hurt, this (2) is a little more hurt, this (3) is more yet, and this (4) is the most hurt you could ever have.”

Children as young as 4 yr

Determine whether child has cognitive ability to use numbers by identifying larger of any two numbers.

Do not give children an option for 0 hurt. Research with Poker Chip Tool has verified that children without pain will so indicate by responses such as, “I don’t have any.”

Ask child, “How many pieces of hurt do you have right now?”

After initial use of Poker Chip Tool, some children internalize the concept “pieces of hurt.” If child gives response such as “I have one right now,” before you ask or before you lay out poker chips, record number of chips on Pain Flow Sheet. Clarify child’s answer by statements such as “Oh, you have a little hurt? Tell me about the hurt.”

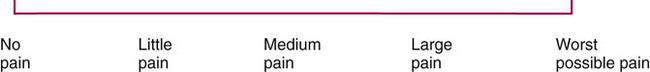

Word-Graphic Rating Scale† (Tesler, Savedra, Holzemer, and Others, 1991)

Uses descriptive words (may vary in other scales) to denote varying intensities of pain

Explain to child, “This is a line with words to describe how much pain you may have. This side of the line means no pain, and over here the line means worst possible pain.” (Point with your finger where “no pain” is, and run your finger along the line to “worst possible pain” as you say it.) “If you have no pain, you would mark like this.” (Show example.) “If you have some pain, you would mark somewhere along the line, depending on how much pain you have.” (Show example.) “The more pain you have, the closer to worst pain you would mark. The worst pain possible is marked like this.” (Show example.) “Show me how much pain you have right now by marking with a straight, up-and-down line anywhere along the line to show how much pain you have right now.” With millimeter rule, measure from the “no pain” end to mark and record this measurement as pain score.

Children 4–17 yr

Numeric Scale

Uses straight line with end points identified as “no pain” and “worst pain” and sometimes “medium pain” in the middle; divisions along line marked in units from 0–10 (high number may vary)

Explain to child that at one end of line is 0, which means that person feels no pain (hurt). At other end is usually 5 or 10, which means the person feels worst pain imaginable. The numbers 1–5 or 1–10 are for very little pain to a whole lot of pain. Ask child to choose number that best describes own pain.

Children as young as 5 yr as long as they can count and have some concept of numbers and their values in relation to other numbers

Scale may be used horizontally or vertically.

Number coding should be same as other scales used in facility.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Pain Assessment and Management in Children

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access