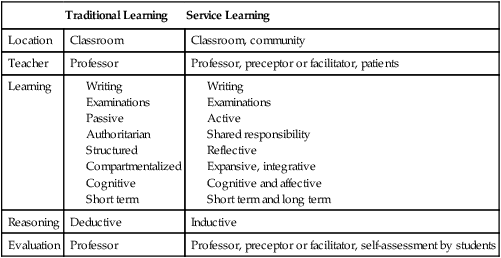

For two decades, agencies and commissions concerned with higher education and preparation of the professions (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2008a; Campus Compact, 2001; National Service-Learning Clearinghouse, 2010; Pew Health Professions Commission, 1998) have recommended that educational programs include experiences that require civic engagement and community involvement. Institutions of higher education and their schools of nursing are therefore seeking opportunities for students to develop moral judgment, civic responsibility, cultural competence, and global awareness, in addition to the basic professional skills set forth in the curriculum. Service learning, a structured component of the curriculum in which students acquire social values through service to individuals, groups, or communities, is one way to provide opportunities for students to develop these values. Service offers opportunities for learning that cannot be obtained any other way. As such, a service experience may be one of the first truly meaningful acts in a student’s life. Service learning uses reflective learning to connect learning with students’ thoughts and feelings in a deliberate way, creating a context in which students can explore how they feel about what they are thinking, and what they think about how they feel. As it does so, service learning becomes an integral part of students’ education. This chapter explains how service learning can contribute to these outcomes in nursing curricula. Service learning evolves from a philosophy of education that emphasizes active learning directed toward a goal of social responsibility and civic engagement. Service learning is not merely volunteerism, nor is it a substitute for a field experience or practicum that is a normal part of a course. Service learning is not the same as a nursing clinical experience because the focus of the learning is on meeting the needs of the host community rather than those of the nursing curriculum. Rather, service learning offers a way in which students can develop cultural competence and a sense of civic responsibility congruent with the tenets of social justice and help create a better world by contributing to national renewal (Amerson, 2010). Both the recipient and the student benefit from the experience. Service learning is a component of broader educational goals to promote civic engagement (American Psychological Association, 2007; Colby, Ehrlich, Beaumont, & Stephens, 2003). Civic engagement involves individual and collective actions to address areas of societal concern. Civic engagement may include service-learning projects as well as community-focused faculty research. Like service learning, civic engagement involves structured activities that require the student to work with a community to solve a problem, but unlike service learning, the focus of the activity is to promote civic responsibility and development for citizenship. Often the terms service learning and experiential learning are used interchangeably; however, they are distinct entities. Experiential learning includes hands-on work and has the learning of work-related skills as its major goal. Traditional nursing clinical experiences are an example of experiential learning. In contrast, service learning involves work that meets actual community needs, has as one of its goals the fostering of “a sense of caring for others,” and includes structured time for reflection (Bailey, Carpenter, & Harrington, 2002). Service learning balances the need of the community and the learning objectives of the students. Community agencies are true partners in design, implementation, and evaluation of the experience. Service learning expands the learning environment for students and faculty. Service learning is population focused and therefore provides opportunities for students to act locally to solve social problems (Eads, 1994). Although a number of similarities are present, key differences exist between traditional learning and service learning (Richardson, Billings, & Martin, 1996). These differences are summarized in Table 12-1. Table 12-1 Differences between Traditional Learning and Service Learning Colleges and universities may engage in service learning differently because of different institutional missions and traditions (Jacoby, 1996). Some universities embrace service learning as a philosophy, some as part of their spiritual mission. Others embrace service learning as part of a “commitment to citizenship, civic responsibility and participatory democracy, and still others ground their service learning programs in community partnerships” (Jacoby, 1996, p. 17). Regardless of how universities embrace service learning, service learning must do the following (American Psychological Association, 2007; Eyler & Giles, 1999; Jacoby, 1996; Shah & Glascoff, 1998; Worrell-Carlisle, 2005): 1. Be connected to program and course learning outcomes and promote learning 3. Allow students to engage in activities that address human and community needs via structured opportunities for student learning and development 4. Provide time for guided reflection in discussion, writing, or media 5. Develop a sense of caring, social responsibility, global awareness, and civic engagement 6. Involve activities that have real meaning for the participants and promote deeper learning 7. Address problems that are identified by the community and require problem solving 8. Promote collaborative learning and teamwork 9. Embrace the concept of reciprocity between the learner and the person or organization being served Kolb’s (1984) theory of experiential learning has been widely used as a theoretical basis for designing and analyzing service-learning programs. Reflective observation about the experience is essential to the learning process. It links the concrete experience to abstract conceptualizations of that experience. Learning is increased when students are actively engaged in gaining knowledge through experiential problem solving and decision making (Bailey et al., 2002; Dewey, 1933; Kolb, 1984; Miettinen, 2000). Use of reflection is built on the work of Kolb (1984) and Dewey (1916, 1933, 1938). In service learning, reflection is both a cognitive process (Kolb, 1984; Mezirow, 1990; Schön, 1983) and a structured learning activity (Silcox, 1994). Effective reflection fosters moral development and enhances moral decision making. Moral decisions involve an exercise of choice and a corresponding willingness to accept responsibility for that choice (Gilligan, 1981). Delve, Mintz, and Stewart (1990) developed a service-learning model based on the theories of moral decision making and values clarification (Gilligan, 1982; Kohlberg, 1976). The model includes five phases of development: exploration, clarification, realization, activation, and internalization. It illustrates that service learning is developmental, providing students with an opportunity to move from charity to justice as they become more empathetic. Delve et al. (1990) believe that without that empathy, the student will not come to recognize the members of the patient population as valued individuals in the larger society and as sources for new learning. The pedagogy of service learning has powerful flexibility. It can be based on subject matter or on learning process; it can connect theory and practice; it integrates several different approaches to knowledge and uses of knowledge; it encourages learning how to learn; and it can focus on a wide range of issues, problems, and interests (Pellietier, 1995). Service learning also lends itself to problem-based learning and case study methodologies. A review of the literature on the outcomes of service learning reveals that students benefit from service learning in multiple and integrated ways (Amerson, 2010; Bailey et al., 2002; Batchelder & Root, 1994; Battistoni, 1995; Callister & Hobbins-Garbett, 2000; Carter & Dunn, 2002; Cohen & Kinsey, 1994; Ehrlich, 1995; Fleischauer & Fleischauer, 1994; Giles & Eyler, 1994; Hales, 1997; Herman & Sassatelli, 2002; Macy, 1994; Narsavage, Lindell, Chen, Savrin, & Duffy, 2002; Pellietier, 1995; Redman & Clark, 2002; Reynolds, 2005; Schaffer & Peterson, 2001; Wills, 1992). Benefits can include personal and professional development as well as mastering course outcomes. Direct participation in the service-learning activity assists with socialization into the profession, introduces new technical or professional skills, increases motivation to learn, and encourages self-directed learning (Bailey et al., 2002; Narsavage et al., 2002; Pellietier, 1995; Reynolds, 2005; Wills, 1992). Several schools of nursing have integrated service-learning components into the freshman experience as a way to introduce nursing students to the role of the nurse (Baumberger, Krouse, & Borucki, 2006; Worrell-Carlisle, 2005). Service learning can also be an opportunity for interprofessional learning and developing collaborative relationships with other professions. Although the majority of service learning occurs in undergraduate programs, graduate programs in nursing are beginning to explore community engagement to further develop students’ leadership skills and sense of responsibility, as well as enhancement of their critical thinking skills and learning of academic content (Francis-Baldesari & Williamson, 2008; Narsavage et al., 2002). Service learning has been found to provide a more thorough understanding of “self” and provides insight into personal strengths and weaknesses (Batchelder & Root, 1994; Ehrlich, 1995). It also has been found to contribute to the development of personal vision, moral sensitivity, clarification of values, and spirituality (Ehrlich, 1995; Eyler, Giles, Stenson, & Gray, 2001; Fleischauer & Fleischauer, 1994; Hales, 1997; Macy, 1994). Service learning facilitates academic inquiry by connecting theory and practice, enhancing disciplinary understanding and understanding of complex material, bringing greater relevance to course material, and helping students generalize their learning to new situations (Carter & Dunn, 2002; Cohen & Kinsey, 1994; Ehrlich, 1995; Hales, 1997; Jarosinski & Heinrich, 2010; Schaffer & Peterson, 2001; Williams, 1990). Service-learning experiences also develop critical thinking (Battistoni, 1995; Callister & Hobbins-Garbett, 2000; Herman & Sassatelli, 2002), communication (Reynolds, 2005), collaboration, leadership, and professional skills (Anstee, Harris, Pruitt, & Sugar, 2008; Giles & Eyler, 1994; Hales, 1997; Pellietier, 1995; Schaffer & Peterson, 2001; Wills, 1992). Reising, Allen, and Hall (2006a) found that participating in a blood pressure screening service-learning project in the university community provided skills of blood pressure assessment, history taking, and health counseling. The social impact of service learning includes the development of civic responsibility, increased orientation to volunteerism, increased political and global awareness, development of cultural competence, and improved ethical decision making (Amerson, 2010; Gehrke, 2008; Herman & Sassatelli, 2002; Palmer & Savoie, 2001; Redman & Clark, 2002; Reising, Allen, & Hall, 2006b; Wills, 1992; Worrell-Carlisle, 2005). Students also learn the value of community health promotion (Reising et al., 2006a, 2006b). Identifying benefits to faculty are key to obtaining buy-in because of the time commitment involved. “Faculty engagement in service learning energizes teaching and places greater emphasis on student-centered learning” (Hoebeke, McCullough, Cagle, & St. Clair, 2009, p. 634). Even though faculty may not be on-site with students directly supervising the service activities, significant faculty time commitment is required to plan the assignment, obtain community partners, read student journals, and facilitate reflection sessions. Faculty who link service-learning activities in their courses with their research and service interests have increased commitment to continuing its use. Some universities have adopted the Boyer model of scholarship, which enlarged the scholarship perspective to include teaching, service, and practice, in addition to research. By enlarging the scholarship perspective, Boyer (1990) believed that there would be a stronger connection between universities and the communities they served. This scholarship model facilitates integration of service learning into the faculty member’s academic role as well as promotion and tenure requirements. The Carnegie Academy for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education provides an online gallery of interdisciplinary projects, including those that involve service learning that can be used by faculty to transform their teaching. This gallery is available on the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching’s website at http://gallery.carnegiefoundation.org/gallery_of_tl/castl_he.html. Service learning also has institutional benefits. These include invigoration of the campus educational culture, development of a strong sense of campus community, increased institutional visibility, enhanced appeal to potential donors, and retention of students (Cooper, 1993; Molledahl, 1994; Pellietier, 1995; Rehnke, 1995; Wills, 1992; Worrell-Carlisle, 2005). Service learning invigorates the campus culture by increasing students’ engagement in their own learning, revitalizing faculty, and allowing faculty to mesh service projects with research interests (Hoebeke et al., 2009; Pellietier, 1995; Rehnke, 1995; Wills, 1992). The interdisciplinary nature of service learning helps the campus regain a strong ethos of community, keeps students and faculty more engaged in the life of the college, and contributes to student retention (Hamner, Wilder, Avery, & Byrd, 2002; Pellietier, 1995). By placing service-learning experiences early in the program, for example as a freshman-year experience, the student retention rate can be increased (Worrell-Carlisle, 2005) because students develop self-efficacy and an understanding of the field of study. Increased institutional visibility contributes to increased student recruitment by providing a visible link between the community and the institution and by providing a perception of access to higher education to community members who have not believed higher education to be within their reach (Cooper, 1993; Molledahl, 1994; Pellietier, 1995; Wills, 1992). Service learning enhances the institution’s appeal to potential donors by providing a direct link between the college and the community, and it appeals to donors interested in community service educational reform (Pellietier, 1995). The mentoring environment that is created between students, faculty, staff, administration, and the broader community becomes a “complex ecology of higher education . . . that can provide knowledge, support, and inspiration” (Daloz, Keen, Keen, & Parks, 1996). Service learning also provides a real-world learning environment in the community that facilitates transfer of knowledge and transition to the practice environment. A smooth transition to practice and increased use of community and public health settings were key recommendations for nursing education in the Institute of Medicine (2010) report. The new alliances formed between academic institutions and community service agencies and organizations eliminate or minimize the traditional separation between the “gown and the town.” Cotton and Stanton (1990) indicated that the gap between gown and town is bridged by successful service-learning programs that cultivate “a spirit of reciprocity, interdependence, and collaboration” (p. 101). The community also benefits when colleges and universities include service learning and civic engagement outcomes in their academic programs. For example, Reising et al. (2006b) found that as a result of a service-learning project in which nursing students conducted hypertension screening and health counseling, 1 year later the community recipients had made modifications in their health management behaviors such as diet change and weight loss. In another service-learning course, students in a nursing research course established partnerships with community organizations to develop research proposals, some of which led to submitting for grant funding (Rash, 2005). Benefits to the community may also include students’ increasing awareness of community health needs and an interest in working in community settings (Ligeikis-Clayton & Denman, 2005). While traditional service learning has occurred in community settings, it can also occur within a traditional acute care setting. Hoebeke et al. (2009) noted that service learning within the health care system

Service learning: developing values, cultural competence, and social responsibility

Service learning

Traditional Learning

Service Learning

Location

Classroom

Classroom, community

Teacher

Professor

Professor, preceptor or facilitator, patients

Learning

Reasoning

Deductive

Inductive

Evaluation

Professor

Professor, preceptor or facilitator, self-assessment by students

Theoretical foundations of service learning

Outcomes of service learning

Benefits to students

Benefits to faculty

Benefits to the institution

Benefits to the community

Benefits to the health care system

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree