Science, Policy, and Politics

Mary W. Chaffee

“Pretending that politics and science do not coexist is foolish, and cleanly separating science from politics is probably neither feasible nor recommended.”

—Madelon Lubin Finkel

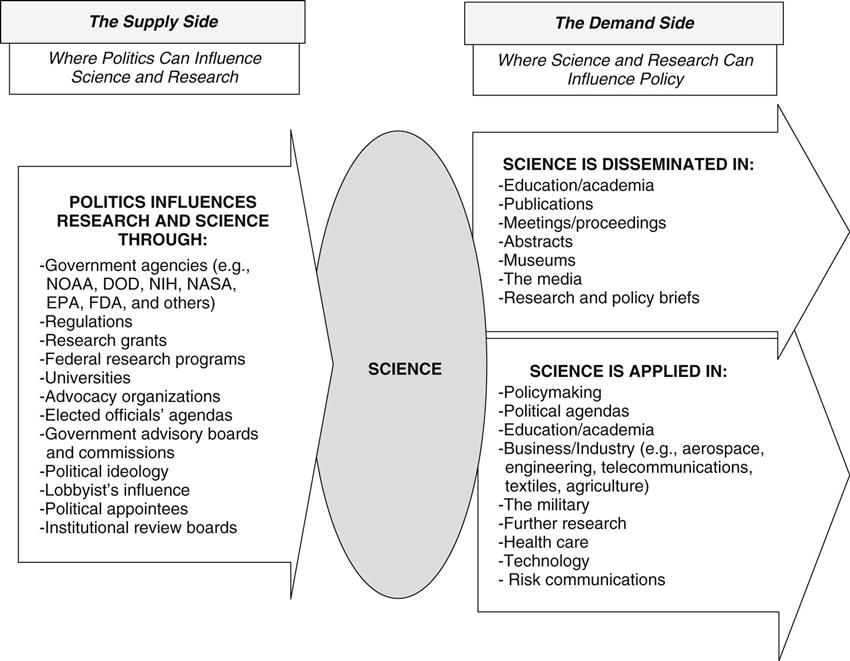

Politics and science often reside together quietly, and their close relationship is not readily apparent. However, conflicts involving the two occur occasionally and draw the attention of the media, the public, and policymakers. This chapter explores how science and politics interact with and influence each other as well as how science can influence policy. This exploration dispels the myth that science is free from political influence. It also illustrates the concept that science can be used productively, or it can be ignored or misused (intentionally or inadvertently) in policymaking. Recognizing the intricate relationships among science, politics, and policy is the first step in making sense of the influence they can exert on each other. To assist, a model is presented that displays the relationships (Figure 39-1). The model depicts the “supply” side of science (research) and the “demand” side of science (science users). It is important for nurses and other health professionals involved in advocacy and policymaking to understand how to use science to shape good policy—as well as to understand how political forces may influence scientific data.

American science is second to none in its productivity, scope, scale, and budget. Since World War II, the scientific community has received extensive resources from the United States government (i.e., the citizens) and has become the world’s greatest scientific enterprise (Greenberg, 2007). Table 39-1 presents some U.S. government agencies involved in the production and regulation of science; this provides a glimpse at the broad scope of scientific activities carried out or supported by the U.S. government.

TABLE 39-1

| Government Science Agency or Organization | Mission or Role |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD | To improve the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of health care for all Americans |

| Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL | One of the U.S. Department of Energy’s oldest and largest national laboratories for science and engineering research |

| Consumer Product Safety Commission, Bethesda, MD | To protect the public from risk of serious injury or death from consumer products |

| Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Arlington, VA | Research and development arm of the U.S. Department of Defense; mission is to maintain technological superiority of the U.S. military and prevent technological surprise from harming national security |

| Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. | To protect human health and the environment |

| Federal Advisory Committees | To provide advice on matters ranging from research funding priorities and awards to strategic planning for federal investment in research |

| Federal Aviation Administration, Washington, D.C. | To provide the safest, most efficient aerospace system in the world |

| Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD | To protect the public health by assuring the safety, efficacy, and security of drugs, biologic products, medical devices, the food supply, cosmetics, and other products |

| House of Representatives Committee on Science and Technology, Washington, D.C. | Committee’s jurisdiction includes all non-defense federal scientific research and development at a number of federal agencies and has special authority to review and study on a continuing basis laws, programs, and government activities relating to non-military research and development |

| Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM | One of the largest science and technology institutions in the world; conducts multidisciplinary research on national security, space, renewable energy, medicine, and nanotechnology |

| National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C. | Brings together committees of experts in all areas of scientific and technological endeavor; includes the Institute of Medicine |

| National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C. | To pioneer the future in space exploration, scientific discovery, and aeronautics research |

| National Highway Transportation Safety Administration, Washington, D.C. | To save lives, prevent injuries, and reduce economic costs due to road traffic crashes, through education, research, standards, and enforcement |

| National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD | Primary agency of the U.S. government responsible for biomedical and health-related research |

| National Institutes of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD | To promote U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing measurement science, standards, and technology in ways that enhance economic security and quality of life |

| National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO | Part of the U.S. Department of Energy; the United States’ primary laboratory for renewable energy and energy efficiency research and development |

| National Science Board, Washington, D.C. | To establish the policies of the National Science Foundation within the framework of policies set forth by the president and Congress |

| National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA | To support fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering |

| U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Disease, Ft. Detrick, MD | To conduct basic and applied research on biologic threats and medical solutions to protect warfighters |

| U.S. Geologic Survey, Reston, VA | Multidisciplinary science organization that focuses on biology, geography, geology, geospatial information, and water; dedicated to the study of the landscape, natural resources, and natural hazards |

| White House Office of Science and Technology and Policy, Washington, D.C. | To advise the president and others in the Executive Office of the President on the effects of science and technology on domestic and international affairs |

Scientific knowledge informs the practice of the clinical disciplines, drives organizational and administrative practices in the health system, and influences access initiatives, cost-control measures, and quality improvement strategies. Pioneering research has led to great benefits for health, wealth, and the nation’s defense, but the corporate presence in science has caused concern, and unscrupulous activities are not unknown (Greenberg, 2001, 2007).

Politics and Science: the Definitions

Politics has been defined as the process of influencing the allocation of scarce resources, and policy is a deliberate course of action. Science is the study, documentation, and collection of evidence pertaining to observable, naturally occurring objects, processes, and phenomena in ways that can be objectively reproduced to verify the results (Shrake, Elfner, Hummon, Janson, & Free, 2006). Research is a process of systematic inquiry using disciplined methods to solve problems or answer questions. Simply put, research is the process of building and refining scientific knowledge (Polit & Beck, 2008). Research develops evidence through numerous methods including case studies, randomized controlled trials, surveys and polls, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and data mining of existing data sources (Diers & Price, 2007).

The Relationships among Science, Politics, And Policy

Research is expensive and the process of funding it is an inherently political one. Research scientists, including nurses, often compete with others for funding by having their research proposals evaluated. Based on proposal reviews, federal agencies, universities, and private organizations award research funding. This is a political process because research funds are a scarce resource allocated according to predetermined criteria. The political influences on science may not always support the selection of the best proposals to receive funding. Greenberg sums up the clash of science and politics by describing science as “a deliberately nonpolitical enterprise embedded in a political system of rewards for vote gathering and campaign fund-raising” (Greenberg, 2001, p. 1). Hegde and Mowery (2008) assert there is political influence on some award decisions by the National Institutes of Health through complex congressional appropriations. There have been broad allegations of presidential meddling in the nation’s science agenda, and interest groups have been accused of using sophisticated political tactics to discredit, suppress, or advance research on potential human health hazards (McGarity, 2006).

Examples of Collisions Between Politics and Science

Many examples exist that illustrate how politics and science sometimes collide; the cases that follow are a sampling.

Phenylpropanolamine (PPA)

PPA was an over-the-counter drug used as an appetite suppressant and decongestant. Reports of strokes in women who had used PPA occurred over a 20-year period, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) raised questions about the drug’s safety. The trade association representing PPA’s manufacturers used scientists and lobbyists to prevent PPA’s removal from the market. Finally, the drug manufacturers and the FDA agreed to select an investigator to design a study of PPA; the findings indicated PPA causes stroke. But, instead of removing the drug from the market, the manufacturers used a product-defense firm to criticize the study. The FDA finally ordered PPA off the market in 2000 (Michaels, 2005).

Evolution and Intelligent Design

In 2005, the clash of politics and science played out in dramatic fashion in Dover, Pennsylvania. Eight members of a school board were sued for requiring that intelligent design be included in the Dover school system’s biology curriculum as an alternative to evolution. Concerned residents challenged the incumbent school board members. Ultimately, all eight members of the school board were voted out of office and replaced by a group of challengers, including nurse Bernadette Reinking, who campaigned against the intelligent design agenda (Goodstein, 2005). The newly elected board members rescinded the intelligent design policy two weeks after Judge John E. Jones III ruled the policy was unconstitutional. Jones stated the concept of intelligent design is religious, not scientific (Raffaele, 2006).

Mammogram Guidelines

Controversy erupted in 2009 when a government panel abruptly changed mammogram screening guidelines. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended routine mammogram screening for women begin at age 50, not age 40 as recommended for the previous 25 years, and that mammograms be done every 2 years rather than annually (Agency for Health Care Quality and Research, 2009). Government guidelines are powerful because they influence the behavior of patients, health care providers, and insurers. In this case, the data may actually support the altered recommendation. Trials in Sweden that monitored 265,000 women found virtually no benefit from mammograms for women under age 55 (Crewdson, 2009). Despite this, the push back has been robust and was fueled by media coverage that failed to explore the potential dangers of unnecessary mammograms. The American Cancer Society has refused to change its recommendation to reflect the new federal guidelines (American Cancer Society, 2009). The Society of Breast Imaging president released a statement that the recommendations are a “step backward and represent a significant harm to women’s health” (Steenhuysen, 2009). Allegations have flown back and forth like tennis volleys and have left some women and health professionals confused about how best to proceed, but the task force was clear that the decision should be made between the patient and provider.

Health Disparities

Policymakers had recognized in 2004 that disadvantaged minority groups received poorer health care and often have poorer health outcomes. Despite this, a draft report by the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ) providing evidence of health disparities was ordered rewritten, and researchers were directed to drop their conclusion that racial disparities are pervasive in the U.S. health care system. The rewrite downplayed the researchers’ conclusions and “broke with the weight of scientific opinion” (Bloche, 2004). Disgruntled government staff members leaked the altered draft reports. Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson ultimately called the episode a mistake and said that the goal had been to produce a report that was more positive (Bloche, 2004). In an analysis of the controversy, Bloche noted, “The affair was embarrassing because Americans expect scientific rigor, not aggressive advocacy, from federal research agencies” (2004).

Lyme Disease Clinical Practice Guidelines

Kraemer and Gostin (2009) chronicled a troubling conflict between the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the Connecticut attorney general. IDSA issued clinical practice guidelines for management of Lyme disease in 2006. The guidelines did not recommend antibiotic treatment for non-specific symptoms (fatigue, headache, and others) that persist after standard antibiotic treatment. The IDSA guidelines also did not recommend the use of alternative diagnostic tests (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration had deemed the tests invalid). The Connecticut attorney general initiated an investigation and alleged the IDSA had violated state antitrust law by recommending against the use of long-term antibiotics to treat “chronic Lyme disease.” Despite developing guidelines that were based on scientific evidence, the IDSA was forced to settle the case after spending more than $250,000 on legal fees (Kraemer & Gostin, 2009).

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Controversy has emerged over the existence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). The American Psychiatric Association is debating whether to add PMDD to the DSM-5 (the fifth edition of its diagnostic manual) due to be published in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2010). Part of the controversy involves whether or not scientific evidence exists to support inclusion of PMDD as a diagnosis. Including PMDD in the DSM-5 would increase the chances that health insurers would cover the cost of PMDD treatment and may encourage further research and development of new therapies (Chen, 2008).

The Death of AHCPR and the Birth of AHRQ

The Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHCPR) was established in 1989. Its mission was to use outcomes research to develop practice guidelines to improve health care cost and quality. Only 6 years later, it was on the brink of closure due to several political realities: A special-interest group launched an attack, the agency had fewer powerful political allies in Congress, it was criticized for inefficiency, and it was target for partisan political attack (Gray, Gusmano, & Collins, 2003). AHCPR published practice guidelines in 1995 supporting nonsurgical treatment for low back pain. The North American Spine Society, an association of spine surgeons, protested the guidelines and underlying research. The Society formed an advocacy organization devoted to shutting down AHCPR (Deyo & Psaty, 1997). Their efforts gained significant traction. After having its budget “zeroed out” by the House of Representatives in 1996, it was resuscitated, given a new name and an altered mission. The new Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, launched in 1999, would no longer produce practice guidelines and the word policy was removed from its name. The agency’s story illustrates the complexities of mixing politics and research.

Controversies during the George W. Bush Administration

Many controversies plagued President George W. Bush’s administration, including perceived manipulation of science and science policy. The Democratic staff of the House Government Committee on Oversight and Government Reform assessed the handling of science and scientists by the Bush Administration and released a report that stated the administration’s “political interference with science has led to misleading statements by the President, inaccurate responses to Congress, altered Web sites, suppressed agency reports, erroneous international communications and the gagging of scientists” (U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, 2003). A Bush political appointee, George Deutsch, resigned after he prevented reporters from interviewing the leading climate scientist at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and instructed a NASA scientist to insert the word theory in discussions of the Big Bang because NASA should not discount the possibility of intelligent design by a creator. Deutsch lied about having a nonexistent undergraduate degree, which led The Washington Post to state in an editorial, “The spectacle of a young political appointee with no college degree exerting crude political control over senior government scientists and civil servants with many decades experience is deeply disturbing” (The Politics of Science, 2006).

While other allegations regarding the Bush administration’s possible manipulation of science policy arose, few were as dramatic as those raised by former U.S. Surgeon General Richard Carmona who served from 2002 to 2006. In testimony before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Carmona stated that public health reports were withheld unless they praised the administration and that he was prevented by political appointees within the Department of Health and Human Services from speaking out on scientific evidence concerning stem cell research, contraception, and sex education. Carmona testified “Anything that doesn’t fit into the political appointee’s ideological, theological, or political agenda is often ignored, marginalized or simply buried” (Vergano, 2007). He added that “The problem with this approach is that in public health, as in a democracy, there is nothing worse than ignoring science or marginalizing the voice of science for reasons driven by changing political winds” (Lee, 2007). The White House denied political interference; spokesman Tony Fratto stated that it was disappointing Carmona “failed to use his position to the fullest extent in advocating for policies he thought were in the best interest of the nation” (KaiserNetwork.org, 2007).

Global Warming

Climate science has generated significant interest since global warming emerged as a potential threat. This science has become embroiled in particularly ugly politicization efforts. “Warmists” believe the evidence of heating in the stratosphere and other types of man-made climate change is compelling (Begley, 2009). “Deniers” contend global warming is an alarmist, political crusade. One particular controversy in the ongoing battle between global warming believers and skeptics concerned “Climate-gate”—the theft of some British climate scientists’ e-mail and the attempt to use them to discredit the science. Hackers stole about 1000 e-mails from scientists in the University of East Anglia’s Climate Research Unit and posted them online. Some of the scientists’ language in the messages was used by skeptics who argued the scientists were engaging in manipulation of their findings to support global warming. The second of three investigations into allegations of research misconduct cleared the scientists; investigators did note the scientists could have used more rigorous statistical procedures (Adam & Eilperin, 2010).

Questions Raised by the Union of Concerned Scientists

The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) is a nonprofit group that combines research and action to urge responsible change in government policy, corporate practices, and consumer choices to promote a healthy environment and safer world (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2010a). The UCS has identified problems in the relationships between science and politics and has proposed solutions. The UCS published the A to Z Guide to Political Interference in Science. This website, using a periodic table–like graphic, presents dozens of cases of perceived political interference in science (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2010b). The Union also published findings from surveys they conducted of government scientists from 2005 to 2007. Participants reported political interference in federal science including direction to alter the reporting of scientific findings, fear of retaliation for speaking out, and being pressured to remove certain language from their communications (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2009).

How Can Science be used to Shape Health Policy?

Evidence should be used to inform policy debates and shape policy choices. To do this effectively requires an understanding of the policy process. Research findings can play a powerful role in the first step of the policy process—getting attention for particular problems and moving them to the policy agenda. Research can be valuable in defining the size and scope of a problem (Diers & Price, 2007); this can help to obtain support for a particular policy option and in advocating for support.

What Can be Done to Ensure a Healthy Partnership between Science and Politics?

A variety of strategies can be employed to see that reliable and valid research is used in policymaking and to prevent inappropriate political influence in science and research. Several strategies are discussed here; additional strategies appear in Table 39-2.

TABLE 39-2

| Strategy | Description |

| Appoint unbiased government panel members | The judgment of the scientific community is injected into policymaking through scientific advisory panels. Allegations have been made that panel members sometimes represent industries regulated by the government. Policymaking would benefit from uncompromised scientific opinion from government advisory panels (Sneyd, 2009). |

| Assess the source of attempts to discredit research findings | Because absolute certainty can rarely be achieved in science, industry groups sometimes attempt to inject “manufactured uncertainty” into the analysis of scientific findings to undermine the findings (Michaels, 2005). |

| Assess the source of funding for research studies | Evaluate the source of funding to determine if the funding entity might have a reason to desire a certain finding. Some industry groups have attempted to manipulate scientific findings to suit their goals. |

| Assess the source of scientific assertions | When science or scientific findings become mired in political controversy, assess the source of the data and who is using it as a political tool. |

| Communicate scientific findings clearly | Communicating effectively bridges the gap between data and application. Scientific information should be carefully considered as to the type of data and the presentation approach to use so it is persuasive to the audience and scientifically defensible (Nelson et al., 2009). |

| Demand scientific integrity | Maintaining high standards of integrity ensures the soundness of the scientific product and the public’s confidence in research findings. |

| Recognize actual and spurious claims of “junk science” | Term describes an advocate’s claims about scientific data, research, or analyses that appear to be spurious; conveys a connotation that the advocate is driven by political, ideologic, financial, or other unscientific motives (Wikipedia, 2010). |

| Protect peer review from interference | Peer review, if done in a balanced and effective manner, can play a powerful role in separating politics from science. If done well, it can keep norms and values in their appropriate places and cause researchers to be explicit about their research premises (Bloche, 2004). |

| Recognize the influence of values on science | The values of scientists are infused into the research process. Values and ethics are an integral, though generally hidden, aspect of decision-making in science (Nelson et al., 2009). |

| Scrutinize the commercialization of academic research relationships with industry partners | The academic-industrial research system produces beneficial results, but concern exists about the penetration of commercialism at some universities (Greenberg, 2007). |

| Use data to raise awareness of problems | One of the most powerful uses of data to increase awareness of a problem came from the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s report “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System” in 1999. A key statistic reported (that 44,000 to 98,000 persons died each year because of preventable medical errors) became an extremely influential research finding. The report, which chronicled the scope of health care errors, generated extensive response and focused the media’s and public’s attention on the problem. |

| Use metaphors to communicate statistical data to audiences and improve comprehension | Metaphors can transform health data into something people can understand and connect to their own lives (Nelson et al., 2009): “College students consumed enough alcohol to fill 3,500 Olympic-sized swimming pools” (Wallack, Dorfman, Jernigan, & Themba, 1993). “Each year, more than 1 million children begin smoking; this is the equivalent of 33,000 classrooms per year or 90 classrooms every day” (Nelson et al., 2009). |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree