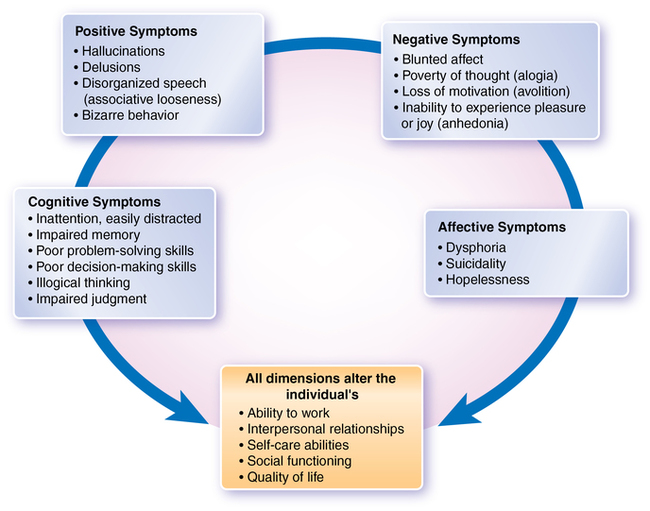

CHAPTER 12 1. Identify the schizophrenia spectrum disorders. 2. Describe the symptoms, progression, nursing care, and treatment needs for the prepsychotic through maintenance phases of schizophrenia. 3. Discuss at least three of the neurobiological-anatomical-genetic findings that indicate that schizophrenia is a brain disorder. 4. Differentiate among the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia in terms of treatment and effect on quality of life. 5. Discuss how to deal with common reactions the nurse may experience while working with a patient with schizophrenia. 6. Develop teaching plans for patients taking first-generation (e.g., haloperidol [Haldol]) and second-generation (e.g., risperidone [Risperdal]) antipsychotic drugs. 7. Compare and contrast the first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics. 8. Create a nursing care plan incorporating evidence-based interventions for symptoms of psychosis, including hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, cognitive disorganization, anosognosia, and impaired self-care. 9. Role-play intervening with a patient who is hallucinating, delusional, and exhibiting disorganized thinking. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders disturb the fundamental ability to determine what is or is not real. In this chapter we will be reviewing concepts important to these disorders. The spectrum disorders are described in Box 12-1; they are listed, in general, from least to most severe. While clinicians contend that the boundaries are so unclear that separate diagnostic labels are not necessarily warranted, for the most current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), the distinctions remain. Children who later go on to be diagnosed with schizophrenia often have unusual characteristics years before psychotic symptoms become apparent (Minzenberger et al., 2011). They tend to do less well in school than their siblings, are less socially engaged, less positive, and exhibit unusual motor development. Actual childhood schizophrenia is extremely rare, carries a worse prognosis than the adult-onset version, and is diagnosed before the age of 12. Adolescents who are later diagnosed with schizophrenia often experience prodromal symptoms (i.e., early symptoms that indicate that a problem may be developing) for a few months or a few years (Minzenberger et al., 2011). Adolescents may experience social withdrawal, irritability, and depression and become antagonistic. Conduct problems and academic decline often bring them to the attention of school and community clinicians. Suspiciousness and low-level distortions in thought seem be especially linked to subsequent schizophrenia. The prevalence of childhood-onset schizophrenia is about 1 in 10,000 children. In adults, the lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia is 1% worldwide with no differences related to race, social status, or culture. It is diagnosed more frequently in males (1.4:1) and among persons growing up in urban areas (Tandon et al., 2008). Schizophrenia usually presents during the late teens and early twenties. Childhood schizophrenia, although rare, does exist, occurring in 1 out of 40,000 children. Early-onset schizophrenia (18 to 25 years) occurs more often in males and is associated with poor functioning before onset, more structural brain abnormality, and increased levels of apathy. Individuals with a later onset (25 to 35 years) are more likely to be female, to have less structural brain abnormality, and to have better outcomes. Substance abuse disorders occur in nearly 50% of persons with schizophrenia and are associated with treatment nonadherence, relapse, incarceration, homelessness, violence, suicide, and a poorer prognosis (Gottlieb et al., 2012). These disorders may represent a maladaptive way of coping with schizophrenia. Nicotine dependence rates in schizophrenia range from 70% to 90% and contribute to an increased incidence of cardiovascular and respiratory disorders (D’Souza & Markou, 2012). Anxiety, depression, and suicide co-occur frequently in schizophrenia. Anxiety may be a response to symptoms (e.g., hallucinations) or circumstances (e.g., isolation, overstimulation) and may worsen schizophrenia symptoms and prognosis. Approximately 10% of persons with schizophrenia commit suicide, a rate 8.5 times that of the general population; both depression and suicide attempts can occur at any point in the illness (Kasckow, Felmet, & Zisook, 2011). Physical health illnesses are more common among people with schizophrenia than in the general population. The risk of premature death is 1.6 to 2.8 times greater than that in the general population; on average, patients with schizophrenia die 28 years prematurely due to disorders such as hypertension (22%), obesity (24%), cardiovascular disease (21%), diabetes (12%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (10%), and trauma (6%) (Miller et al., 2007). Polydipsia can lead to fatal water intoxication (indicated by hyponatremia, confusion, worsening psychotic symptoms, and ultimately coma). Polydipsia occurs in upwards of 20% of persons with schizophrenia and a seemingly insatiable thirst that results causes hyponatremia in 2-5%; contributing factors include antipsychotic medication (causes dry mouth), compulsive behavior, and neuroendocrine abnormalities (Goldman, 2009). The scientific consensus is that schizophrenia occurs when multiple inherited gene abnormalities combine with nongenetic factors (e.g., viral infections, birth injuries, environmental stressors, prenatal malnutrition), altering the structures of the brain, affecting the brain’s neurotransmitter systems, and/or injuring the brain directly (Tandon et al., 2008). This is called the diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia (Walker & Tessner, 2008). Schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like symptoms, such as eccentric thinking, occur at an increased rate in relatives of individuals with schizophrenia. According to Giegling and colleagues (2010): • Compared to the usual 1% risk in the population, having a first-degree relative with schizophrenia increases the risk to nearly 10%. • Concordance rates in twins (how often one twin will have the disorder when the other one has it) is about 50% for identical twins and about 15% for fraternal twins. • The degree to which genetics plays a role in causing schizophrenia is estimated at 65-80% Evidence suggests that multiple genes on different chromosomes interact with each other in complex ways to create vulnerability for schizophrenia. Genes potentially linked to schizophrenia continue to be identified, suggesting a high degree of complexity (Tandon et al., 2008). The first antipsychotic drugs are known as conventional (or first-generation) antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol and chlorpromazine). These drugs block the activity of dopamine-2 (D2) receptors in the brain, limiting the activity of dopamine and reducing some of the symptoms of schizophrenia. Cocaine, methylphenidate (Ritalin), and levodopa increase the activity of dopamine in the brain and, in biologically susceptible persons, may bring on schizophrenia. Amphetamines can be used to induce a model of schizophrenia in persons without schizophrenia and can precipitate the disorder; in fact, almost any drug of abuse, including marijuana, can lead to schizophrenia in biologically vulnerable persons (Callaghan et al., 2012). Because the dopamine-blocking agents do not alleviate all the symptoms of schizophrenia, it seems likely that other neurotransmitters or other factors may be involved. Researchers have long been aware that phencyclidine piperidine (PCP) induces a state closely resembling schizophrenia. This observation led to interest in the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor complex and the possible role of glutamate in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Glutamate is a crucial neurotransmitter during periods of neuromaturation; abnormal maturation of the central nervous system (CNS) is considered to be a central factor contributing to information-processing deficits in schizophrenia (Kegeles et al., 2012). Acetylcholine (Ach), active in the muscarinic system, is another implicated neurotransmitter and is emerging as an important target for future treatment (Jones, Byun, & Bubser, 2012). Disruptions in communication pathways in the brain are thought to be severe in schizophrenia. It is possible that structural abnormalities cause such disruption. Using brain imaging techniques—computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET)—researchers (Hulshoff et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2011; van Haren et al., 2011) have provided substantial evidence that some people with schizophrenia have structural brain abnormalities, including the following: • Enlargement of the lateral cerebral ventricles, third ventricle dilation, and/or ventricular asymmetry • Reduced cortical, frontal lobe, hippocampal and/or cerebellar volumes • Increased size of the sulci (fissures) on the surface of the brain PET scans also show a lowered rate of blood flow and glucose metabolism in the frontal lobes, which govern planning, abstract thinking, social adjustment, and decision making, all of which are affected in schizophrenia. Figure 3-5 in Chapter 3 shows a PET scan demonstrating reduced brain activity in the frontal lobe of a patient with schizophrenia. Such structural changes may worsen as the disorder continues. Postmortem studies on individuals with schizophrenia reveal a reduced volume of gray matter in the brain, especially in the temporal and frontal lobes; those with the most tissue loss had the worst symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions, bizarre thoughts, and depression). A history of pregnancy or birth complications is associated with an increased risk for schizophrenia. Prenatal risk factors include poor nutrition (e.g., folate deficiency) and hypoxia. Infectious agents such as human herpes virus 2 and human endogenous retrovirus 2 are also implicated (Arias et al., 2011). Psychological trauma to the mother during pregnancy (e.g., the death of a relative) can also contribute to the development of schizophrenia (Khashan et al., 2008). Other risk factors include a father older than 35 at the child’s conception and being born during late winter or early spring (Tandon et al., 2008). Stress increases cortisol levels, impeding hypothalamic development and causing other changes that may precipitate the illness in vulnerable individuals. Schizophrenia often manifests at times of developmental and family stress, such as beginning college or moving away from one’s family. Social, psychological, and physical stressors may play a significant role in both the severity and course of the disorder and the person’s quality of life. Other factors increasing the risk of schizophrenia include childhood sexual abuse, exposure to social adversity (e.g., living in chronic poverty or high-crime environments), migration to or growing up in a foreign culture, and exposure to psychological trauma or social defeat (Tandon et al., 2008). The person may feel that something “strange” or “wrong” is happening. Routine stimuli such as traffic noise or voices in a café can become overwhelming. Events are misinterpreted, and mystical or symbolic meanings may be given to ordinary events. For example, the patient may think that certain colors have special powers or that a song on the radio is a message from God intended just for him. Discerning others’ emotions from facial expression or tone of voice becomes more difficult, and others’ actions or words may be mistaken for signs of hostility or evidence of harmful intent (Gold et al., 2012). Schizophrenia usually progresses through predictable phases, although the presenting symptoms during a given phase and the length of the phase can vary widely; these phases are (Chung et al., 2008): • Phase I—Acute: Onset or exacerbation of florid, disruptive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions, apathy, withdrawal) with resultant loss of functional abilities; increased care or hospitalization may be required. • Phase II—Stabilization: Symptoms are diminishing, and there is movement toward one’s previous level of functioning (baseline); partial hospitalization or care in a residential crisis center or a supervised group home may be needed. • Phase III—Maintenance: The patient is at or nearing baseline (or premorbid) functioning; symptoms are absent or diminished; level of functioning allows the patient to live in the community. Ideally, recovery with reduced or no residual symptoms has occurred. Therefore, early assessment plays a key role in improving the prognosis for persons with schizophrenia (Chung et al., 2008). This form of primary prevention involves monitoring those at high risk (e.g., children of parents with schizophrenia) for symptoms such as abnormal social development and cognitive dysfunction. Intervening to reduce stressors (i.e., reduce or avoid exposure to triggers), enhancing social and coping skills (i.e., build resiliency), and administering prophylactic antipsychotic medication may also be of benefit. Not all people with schizophrenia (or even people with the same subtype of the disorder) have the same symptoms, and some of the symptoms of schizophrenia are also found in other disorders. Figure 12-1 describes the four main symptom groups of schizophrenia: 1. Positive symptoms: The presence of something that is not normally present (e.g., hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behavior, paranoia, abnormal movements, gross errors in thinking) 2. Negative symptoms: The absence of something that should be present (e.g., interest in hygiene, motivation, ability to experience pleasure) 3. Cognitive symptoms: Often subtle changes in memory, attention, or thinking (e.g. impaired executive functioning [the ability to set priorities or make decisions]) 4. Affective symptoms: Symptoms involving emotions and their expression The most common delusions are persecutory, grandiose, or those involving religious or hypochondriacal ideas. Table 12-1 provides definitions and examples of types of delusions. A delusion may be a response to anxiety or reflect areas of concern; for example, someone with poor self-esteem may believe he is Beethoven or an emissary of God, leading him to feel more powerful or important. Looking for and addressing such underlying themes or needs can be a key nursing intervention. TABLE 12-1 *A false belief held and maintained as true regardless of evidence to the contrary. This does not include sharing unusual beliefs maintained by one’s culture or subculture. Echolalia is the pathological repeating of another’s words and is often seen in catatonia. Other disorders of thought or speech include: • Religiosity: An excessive preoccupation with religious themes. • Magical thinking: Believing that one’s thoughts or actions can affect others; this is common in children (e.g., wearing pajamas inside out to make it snow). • Paranoia: An irrational fear of others, ranging from mild (wariness, guardedness) to profound (believing that another person intends to kill you). Note that persons who fear others may sometimes act defensively, harming the other person before that person harms the patient; this creates a risk to others. • Circumstantiality: Including unnecessary and often tedious details in one’s conversation (e.g., describing your breakfast when asked how your day is going). • Tangentiality: Leaving the main topic to talk about less important information; going off on tangents in a way that takes the conversation off-topic. • Cognitive retardation: A generalized slowing in the pace of thinking, represented by delays in responding to questions or difficulty finishing one’s thoughts. • Alogia, or poverty of speech: A reduction in spontaneity or volume of speech, represented by a lack of spontaneous comments and overly brief responses. • Flight of ideas: Moving rapidly from one thought to the next, making it difficult for others to follow the conversation. • Thought blocking: A reduction in the amount of thinking; an abrupt stoppage of thought that derails conversation. • Thought insertion: Feeling that one’s thoughts are not one”s own or that they were inserted into one’s mind. • Thought deletion: A belief that one’s thoughts have been taken or are missing. • Illogical, disorganized or bizarre thinking • Inability to maintain attention: Represented by easy distractibility, off-topic comments in group, or unfinished tasks. • Depersonalization: A feeling that one is somehow different or unreal or has lost his identity. People may feel that body parts do not belong to them or may sense that their body has drastically changed (e.g., a patient may see her fingers as being smaller or more distant, or not her own). • Derealization: A false perception that the environment has changed (e.g., everything seems bigger or smaller, or familiar surroundings seem somehow strange and unfamiliar). • Auditory: Hearing voices or sounds • Visual: Seeing persons or things • Gustatory: Experiencing tastes • Catatonia: A pronounced increase or decrease in the rate and amount of movement; the most common form is stuporous behavior in which the person moves little or not at all. • Motor retardation: A pronounced slowing of movement. • Motor agitation: Excited behavior such as running or pacing rapidly, often in response to internal or external stimuli; it can pose a risk to the patient (e.g., exhaustion, collapse, and even death) or others (being knocked down). • Stereotyped behaviors: Repeated motor behaviors that do not serve a logical purpose. • Waxy flexibility: The extended maintenance of posture, usually seen in catatonia. For example, the nurse raises the patient’s arm, and the patient continues to hold this position in a statue like manner. • Echopraxia: The mimicking of movements of another. It is also seen in catatonia. • Negativism: Akin to resistance but may not be intentional. The patient does the opposite of what he or she is told to do (active negativism) or fails to do what is requested (passive negativism). • Impaired impulse control: A reduced ability to resist one’s impulses. Examples include interrupting in group or throwing unwanted food on the floor. • Gesturing or posturing: Assuming unusual and illogical expressions (often grimaces) or positions. • Boundary impairment: An impaired ability to sense where one’s body or influence ends and another’s begins. For example, a patient might stand too close to others or might drink another’s beverage, believing that, because it is near him, it is his. • Initiate and maintain conversations and relationships • Obtain and maintain employment • Make decisions and follow through on plans Negative symptoms contribute to poor social functioning and social withdrawal. During the acute phase, they are difficult to assess because positive symptoms (such as delusions and hallucinations) dominate. See Table 12-2 for these and other negative symptoms. TABLE 12-2 NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS OF SCHIZOPHRENIA • Flat: Immobile or blank facial expression • Blunted: Reduced or minimal emotional response • Inappropriate: Incongruent with the actual emotional state or situation (e.g., a man laughs when a peer threatens him) • Bizarre: Odd, illogical, grossly inappropriate, or unfounded; includes grimacing and giggling

Schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders

![]() http://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/ST/halter7epre/index.html?location=halter/four/twelve

http://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/ST/halter7epre/index.html?location=halter/four/twelve

Clinical picture

Epidemiology

Comorbidity

Etiology

Biological factors

Genetic

Neurobiological

Dopamine theory.

Other neurochemical hypotheses.

Brain structure abnormalities

Psychological and environmental factors

Prenatal stressors

Psychological stressors

Course of the disorder

Phases of schizophrenia

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

Prepsychotic phase

General assessment

Positive symptoms

DELUSION

DEFINITION

EXAMPLE

Control

Believing that another person, group of people, or external force controls thoughts, feelings, impulses, or behavior

Brian covered his apartment walls with aluminum foil to block governmental efforts to control his thoughts.

Ideas of Reference

Giving personal significance to unrelated or trivial events; perceiving events as relating to you when they are not

Barbara believes that the birds sing when she walks down the street just for her.

Persecution

Believing that one is being singled out for harm by others; this belief often takes the form of a plot by people in power

Peter believed that the Secret Service was planning to kill him by poisoning his food; therefore, he would eat only prepackaged food.

Grandeur

Believing that one is a very powerful or important person

Sam believed he was a famous playwright and tennis pro.

Somatic Delusions

Believing that the body is changing in unusual ways (e.g., rotting inside)

David said his heart had stopped and was rotting away.

Erotomanic

Believing that another person desires you romantically

Although he barely knew her, Patti insisted that Eric would marry her if only his current wife would stop interfering.

Jealousy

Believing that one’s mate is unfaithful

Sally wrongly accused her spouse of going out with other women. Her proof was that he twice came home from work late (even though his boss explained that everyone had worked late).

Negative symptoms

NEGATIVE SYMPTOM

DESCRIPTION

Affective blunting

A reduction in the expression, range, and intensity of affect (In flat affect, no facial expression is present.)

Anergia

Lack of energy; passivity, lack of persistence at work or school

Anhedonia

Inability to experience pleasure in activities that usually produce it

Avolition

Reduced motivation and spontaneous activity; inability to initiate tasks such as social contacts, grooming, and other activities of daily living (ADLs)

Poverty of content of speech

While adequate in amount, speech conveys little information because of vagueness or superficiality

Poverty of speech

Reduced spontaneity and amount of speech; rarely initiates speech and responds in brief or one-word answers

Thought blocking

A sudden interruption in the thought process, usually due to internal stimuli. Example: A patient abruptly stops talking in the middle of a sentence and remains silent.

Nurse: What just happened now?

Patient: I forgot what I was saying. Something took my thoughts away.

Schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access