Retail Health Care Clinics

Filling a Gap in the Health Care System

Donna L. Haugland and Patricia J. Hughes1

“There’s a way to do it better—find it.”

—Thomas Edison

It was a long wait that evening in 1999 when Rick Krieger needed diagnosis and treatment for his son’s sore throat (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008). With limited choices for after-hours care, he sat in an urgent care center for over 2 hours. He became frustrated with the wait, the slow service, the cost, and the overengineered processes for a common, simple throat infection. One year later, he and his business associates opened a walk-in clinic at a strip mall under the name QuickMedx (now MinuteClinic, L.L.C. [MinuteClinic]) and created a whole new sector in the health care industry—retail clinics. Christensen (2007) hailed creation of the retail clinic as one of the top 10 disruptive innovations of the decade. The retail clinic has reshaped the health care marketplace through the core concepts of disruptive innovation: simplicity, accessibility, convenience, and affordability. This shift in the health care marketplace also has produced a new model of nurse-led service delivery.

A New Approach to Accessing Care

The term “retail clinic” certainly sounds a bit strange. However, it appropriately communicates the fact that the care is delivered at medical clinics located in retail outlets, such as pharmacies, groceries, and mass merchandisers. The typical retail clinic or convenient care clinic is usually 200 to 500 square feet large, located near the business’s pharmacy, sparsely furnished to accommodate 15-minute appointments, and staffed by a nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (Scott, 2006). Retail clinics do not offer the full array of acute, chronic, and preventive services found in primary care or urgent care. The focus is on common acute illnesses, such as sore throat and urinary tract infection, as well as vaccinations and limited screenings, such as cholesterol testing. But, the 10 most common conditions managed in retail clinics account for 12% of emergency department (ED) visits (Mehrotra, Wang, Lave, Adams & McGlynn, 2008).

The term retail clinic connotes retail principles that are at the core of the concept—consumer focus, competitive pricing, convenience, efficient service, extended operating hours, and products with consistent quality. These clinics are open during evenings and weekends, usually offer short wait times, require no appointment, and post the menu and prices of their limited offerings. This is a radically different approach from the way health care historically has been delivered in the United States, requiring trips to medical campuses away from the person’s daily routine, limiting office visits to weekday business hours, and enduring wait times of up to several days for an episodic illness.

Price transparency also is not seen in traditional health care settings since they typically do not post the cost of services. Yet, in the consumer-driven health care marketplace, the overall cost—not just out-of-pocket cost—is an important consideration in choosing a provider (Fronstin & Helman, 2009). Retail clinics usually can provide a bargain for the health care shopper. Low overhead costs from their small spaces, lack of expensive equipment, minimal or no support staff, and lower salaries for non-physician providers allow retail clinics to offer lower costs for the services that they offer—approximately 30% to 40% less than in a physician’s office and 80% less than in an emergency department (Mehrotra et al., 2009).

Consumer Response

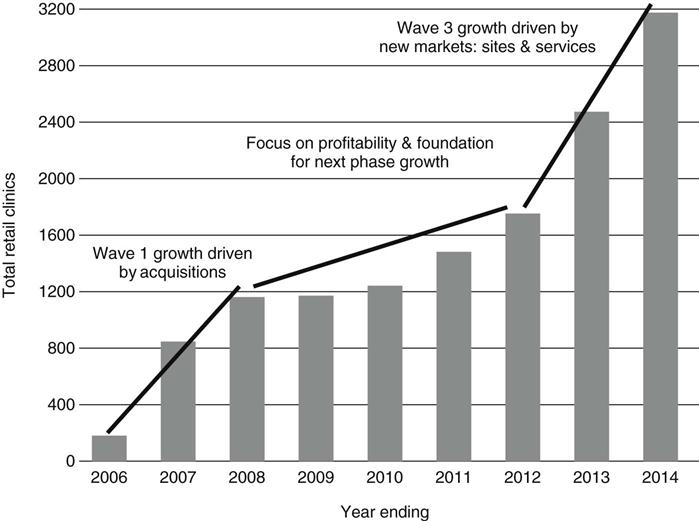

Since its debut in 2000, the retail health care sector has grown to over 1100 clinics located in 38 states and the District of Columbia (Retail Clinics, 2009) (Figure 31-1). This expansion has been attributed to the consistently favorable response to and growing adoption of the retail clinic model on the part of consumers (Keckley, Underwood, & Gandhi, 2009). One recent survey indicates that 16% of respondents have sought care at a retail clinic within the past 2 years (Deloitte Center for Health Solutions, 2009), representing millions of patient visits. About 90% of these visits were for 10 simple acute illnesses, including upper respiratory tract infection, pharyngitis, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, otitis media, and urinary tract infection (Mehrotra et al., 2008). Nearly two-thirds of customers cited the convenient hours and locations as major factors in choosing retail clinics instead of other sources of care (Tu Ha & Cohen, 2008). Overall satisfaction rate has been 90%, with some retail clinic operators reporting rates higher than 95% (New WSJ.com, 2008; Hunter, Weber, Morreale, & Wall, 2009). This contrasts starkly with patient satisfaction rates of 71% for primary care physicians (Deloitte Center for Health Solutions, 2009).

Despite this high satisfaction, more than three-fourths of those surveyed believed the retail clinic is appropriate only for basic medical care when a person’s regular provider is unavailable. Nearly two-thirds of consumers have reported concerns about staff qualifications and the possibility that serious problems might be missed or diagnosed incorrectly (New WSJ.com, 2008). What remains unclear is whether these concerns stem from unfamiliarity with a new and evolving model, lack of consumer awareness about NPs and their scope of practice, or a combination of both. The level of concern has decreased slightly between 2005 and 2008 (New WSJ.com, 2008). However, the public still has limited awareness of NPs and what they can do (Green, 2007). Their understanding is confounded by the many kinds of nurses, each with different nomenclature and scope of practice. For NPs, role confusion also is fostered by the state-by-state variation in professional designations and degree of physician oversight. Whether or not retail clinics can serve as a vehicle for promoting the image and acceptance of NPs as autonomous care providers remains an open question.

Reactions from the Health Care Community

While a few business futurists, such as Harvard Business School’s Clayton Christensen (2007), embraced the change as an “innovative disruption,” initial reactions from stakeholders in health care varied from tepid to negative. However, as retail clinics continue to strengthen a foothold in the marketplace, some segments have accepted the model as a positive indicator of future solutions for health care reform.

Third-Party Payers.

The original retail clinics operated on a fee-for-service, cash payment basis. However, in response to the demands of their members for more voice in consumer-directed health care, major health plans began to add retail clinics to their provider networks. Early on, they applied urgent care or emergency department co-payments, but some have reduced or waived them as retail clinics demonstrated a cost-savings proposition (Scott, 2007). For example, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota decided to waive co-payments after its study of claims showed that a retail clinic visit cost half as much as a visit at a primary care office (Krizner, 2006), saving the company more than $1.25 million in health care costs during 2007 (Wilson, 2009). Employers, too, discounted co-payments in an effort to capitalize both on cost savings and the reduced time employees were away from work due to illness (Silva, 2007). Currently, almost all retail clinics accept insurance and Medicare fee-for-service reimbursement, and only 16% of patients pay out-of-pocket for their visits (Mehrotra et al., 2008; Rudavsky, Pollack, & Mehrotra, 2009).

However, coverage issues still present challenges to the growth of the retail clinic industry. Some plans continue to require a larger co-payment than that for primary care providers. Many payers limit coverage only to services they deem appropriate for the retail setting instead of reimbursing the full menu of clinics’ services (Kantor, 2007). Finally, for some insurers, clinic operators must renegotiate contracts whenever a new service is offered, even though it falls within an NP’s scope of practice and skill set.

Nurse Practitioners.

Nurse practitioner leaders initially complained that the limited number of minor conditions managed in the retail clinic represented an oversimplified practice that not only failed to utilize the full potential of the NP’s education and skills, but also ran the risk of distorting the public’s perception of the NP role (Green, 2007). However, professional nurse practitioner associations have collaborated on principles for retail clinics that support nurse practitioner practice and now see it as a way to expand and enhance the NP profession and help to educate the public about nurse practitioner practice (American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 2007).

Physicians.

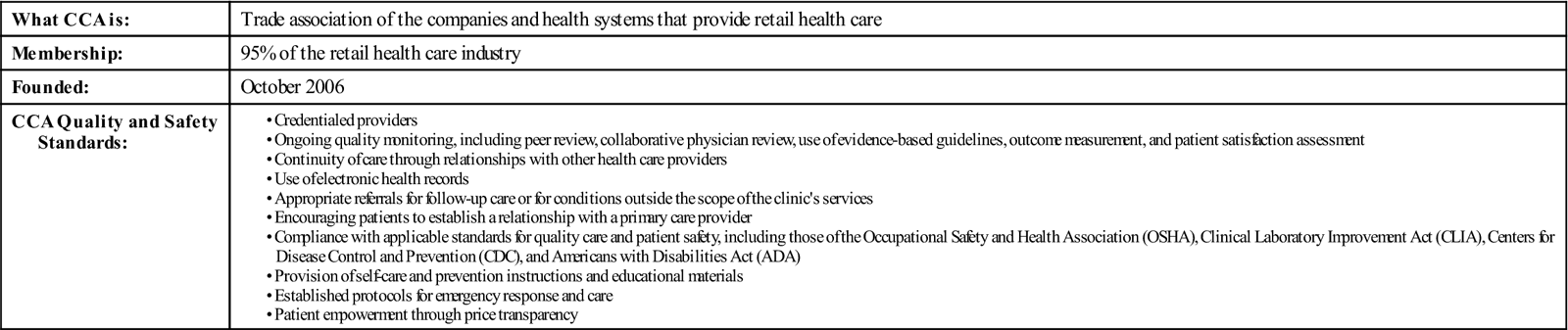

Many of the most vocal critics of the retail health care model have been from physicians. As Sage (2009, p. 8) asserted, “physicians would prefer to label and hopefully control retail clinics … using familiar narratives of quackery, corporatization, profit-seeking, and conflict of interest.” The official stance of major physician organizations, such as the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American Academy of Pediatrics, was disapproval of retail clinics. As the number of retail clinics grew, the AAFP formed a Retail Medicine Workgroup in 2005 that collaborated with the largest retail health companies “to shape the emerging retail clinics in a way that could benefit patients” (Sullivan, 2006, p. 68) through development of desirable attributes and principles, such as limited scope of services, support of the medical home, collaborative relationships with local medical providers, and use of electronic medical records. Other medical organizations then promulgated similar guidelines. Operators of retail clinics endorsed these standards because they reflected practices consistent with quality and patient safety, and, in many cases, already were in place in most retail clinic environments. Subsequently, the Convenient Care Association (CCA), which represents more than 20 of the largest operators, published even more stringent quality and safety standards that its members have committed to meet (Table 31-1). MinuteClinic, a CCA member, set the benchmark with its Joint Commission accreditation in 2006 and reaccreditation in 2009. Accreditation was an important milestone for retail clinics because it demonstrated adherence to the same rigorous standards and quality requirements applicable to prominent health care facilities operating within the more traditional medical system.

TABLE 31-1

Convenient Care Association (CCA)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree