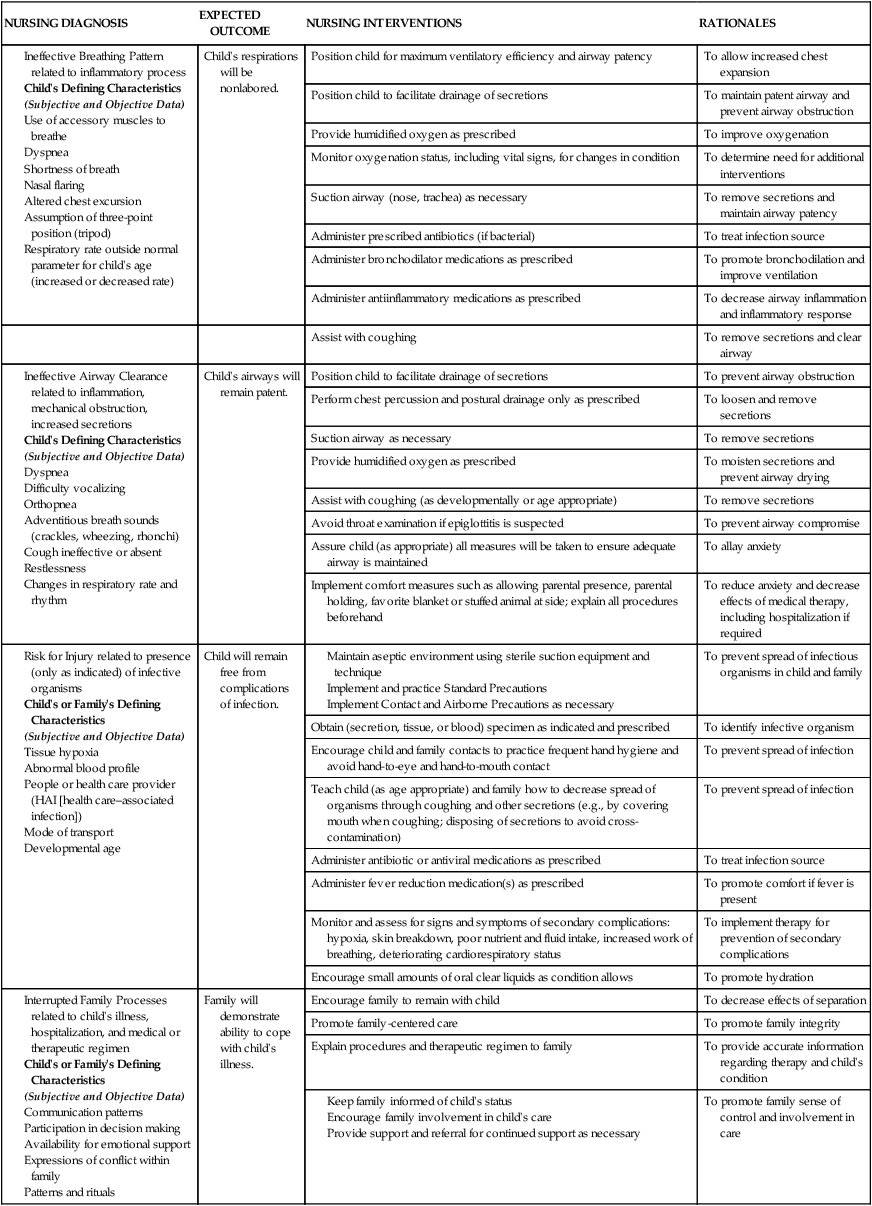

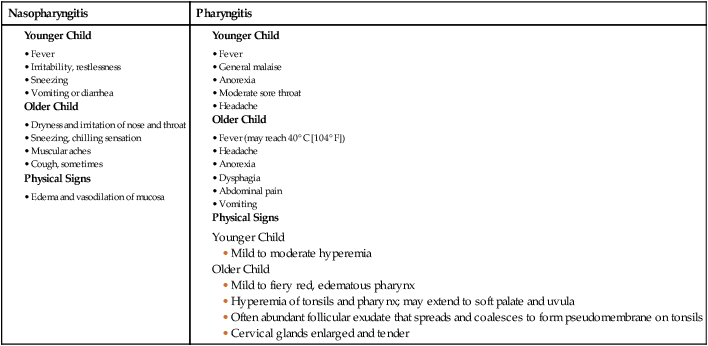

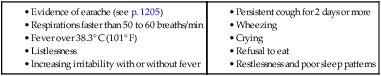

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify the factors leading to respiratory tract infection in the infant and young child. • Contrast the effects of various respiratory infections observed in infants and children. • Describe the postoperative nursing care of the child with an adenotonsillectomy. • Outline a nursing care plan for a child with croup. • Outline a nursing care plan for a child with acute otitis media. • Demonstrate an understanding of the ways in which inhalation of noninfectious irritants produce pulmonary dysfunction. • Describe the ways in which the various therapeutic measures relieve the symptoms of asthma. • Outline a plan for teaching home care for the child with asthma. • Describe the physiologic effects of cystic fibrosis on the gastrointestinal, endocrine, reproductive, and pulmonary systems. • Outline a plan of care for the child with cystic fibrosis. • List the major signs of respiratory distress in infants and children. • Describe the nursing care for a child with respiratory failure. Assessment of the respiratory system follows the guidelines described in Chapter 29 (for assessment of the ears, nose, mouth and throat, chest, and lungs). The assessment should include respiratory rate, depth, and rhythm; heart rate; oxygenation; hydration status; body temperature; activity level; and level of comfort. Special attention should also be given to the components and observations listed in Box 40-2. A noninvasive pulse oximeter (oxygen saturation) measurement should be performed on all children as part of the routine physical assessment. The nursing process in the care of the child with acute respiratory tract infection is outlined in the Nursing Care Plan. Dehydration is a potential complication when children have respiratory tract infections and are febrile or anorectic, especially when vomiting or diarrhea is present. Infants are especially prone to fluid and electrolyte deficits when they have a respiratory illness because a rapid respiratory rate that accompanies such illnesses precludes adequate oral fluid intake. In addition, the presence of fever increases the total body fluid turnover in infants. If the infant has nasal secretions, this further prevents adequate respiratory effort by blocking the narrow nasal passages when the infant reclines to bottle feed or breastfeed and ceases the compensatory mouth breathing effort, thus causing the child to limit intake of fluids. Adequate fluid intake is encouraged by offering small amounts of favorite fluids (clear liquids if vomiting) at frequent intervals. Oral rehydration solutions, such as Infalyte or Pedialyte, should be considered for infants, and water or a low-carbohydrate (≤5 g per 8 oz) flavored drink should be considered for older children. Fluids with caffeine (tea, coffee) should be avoided because these may act as diuretics and promote fluid loss. Sports drinks and energy drinks are not recommended for oral rehydration (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2011); some sports drinks may be diluted for older children. When encouraging oral fluids to prevent dehydration, sports drinks with “replacement electrolytes” offer no benefit over water and should be used cautiously in small children. Breastfeeding infants should continue to be breastfed because human milk confers some degree of protection from infection (see Chapter 23). Fluids should not be forced, and children should not be awakened to take fluids. Forcing fluids creates the same problem as urging unwanted food. Gentle persuasion with preferred beverages or sugar-free popsicles is usually more successful. Younger children may like to drink smaller amounts from a plastic medicine cup. To assess their child’s level of hydration (see Chapter 41), parents are advised to observe the frequency of voiding and to notify the nurse or health care practitioner if there is insufficient voiding. Counting the number of wet diapers in a 24-hour period is a satisfactory method to assess output in infants and toddlers. In the hospital, diapers are weighed to assess output, which should be at least 1 mL/kg/hr up to 30 kg in child’s weight. Then it should be at least 30 mL per hour in patients weighing more than 30 kg. The practitioner should be notified if the urine output is low. Loss of appetite is characteristic of children with acute infections. In most cases, children can be permitted to determine their own need for food. Many children show no decrease in appetite, and others respond well to foods such as gelatin, soup, and puddings (see Feeding the Sick Child, Chapter 39). Urging foods on anorexic children may precipitate nausea and vomiting and cause an aversion to feeding that may extend into the convalescent period and beyond. Young children with respiratory tract infections are irritable and difficult to comfort; therefore the family needs support, encouragement, and practical suggestions concerning comfort measures and administration of medication. In addition to antipyretics and nose drops, the child may require antibiotic therapy. Parents of children receiving oral antibiotics must understand the importance of regular administration and continuing the drug for the prescribed length of time, regardless of whether the child appears ill. Parents should be cautioned against giving their child any medications that are not approved by the health care practitioner and to avoid giving antibiotics left over from a previous illness or prescribed for another child. Administering unprescribed antibiotics can produce serious side effects and adverse reactions (see Chapter 39 for administration of medications and teaching parents). See also the Nursing Care Plan on p. 1198. Acute nasopharyngitis, or the equivalent of the “common cold,” is caused by the rhinovirus, RSV, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, influenza virus, and parainfluenza virus. Symptoms are more severe in infants and children than in adults. Fever is common in young children, and older children have low-grade fevers, which appear early in the course of the illness. Other clinical manifestations are listed in Box 40-3. Symptoms may last up to 10 days. Children with nasopharyngitis are managed at home. There is no specific treatment, and effective vaccines are not available. Antipyretics may be indicated for mild fever and discomfort (see Chapter 39 for management of fever). Rest is recommended. The provision of a humidified environment and increasing oral fluids may be beneficial to some children with a cold. Cough suppressants containing dextromethorphan should be used with caution (cough is a protective way of clearing secretions) but may be prescribed for a dry, hacking cough, especially at night. However, some preparations contain 22% alcohol and can cause adverse effects such as confusion, hyperexcitability, dizziness, nausea, and sedation. Parents should monitor the child carefully for potential adverse effects. Recent concerns regarding serious side effects of cough and cold preparations in young children, particularly infants, and lack of convincing evidence that such medications are effective in reducing symptoms have prompted recommendations by health care experts to carefully evaluate the benefits and risks of recommending such preparations for children younger than 6 years (Bell and Tunkel, 2010; Ryan, Brewer, and Small, 2008; Vassilev, Kabadi, and Villa, 2010). Over-the-counter cold preparation such as pseudoephedrine and some antihistamines are not appropriate for the treatment of the common cold in infants and toddlers; these may cause serious side effects in such children and have been associated with death in infants (Rimsza and Newberry, 2008; Ryan, Brewer, and Small, 2008). Antihistamines are largely ineffective in treatment of nasopharyngitis (Kinyon Munch, 2010). These drugs have a weak atropine-like effect that dries secretions, but they can cause drowsiness or, paradoxically, have a stimulatory effect on children. Second-generation antihistamines such as loratadine or cetirizine are nonsedating but also have not been shown to be effective in relieving the symptoms of the common cold in small children and are not recommended by the American College of Chest Physicians (Pratter, 2006). There is no support for the usefulness of expectorants, and antibiotics are usually not indicated because most infections are viral. Supportive treatment with antipyretics, nasal saline irrigation, and adequate fluid hydration is still the safest and most often recommended therapy for infants and small children with the common cold (Kinyon Munch, 2010). Support and reassurance are important elements of care for families of young children with recurrent upper respiratory infections (URIs). Because URIs are frequent in children younger than 3 years, families may feel they are on an endless roller coaster of illness. They need reassurance that frequent colds are a normal part of childhood and that by 5 years of age, their children will have developed immunity to many viruses. When children spend time in day care centers, their infection rate is higher than if they are cared for in the home because of increased exposure. Parents should know the signs of respiratory complications and should notify a health care professional if complications occur or the child does not improve within 2 to 3 days (Box 40-4). Children who experience GABHS infection of the upper airway (strep throat) are at risk for rheumatic fever (RF), an inflammatory disease of the heart, joints, and central nervous system (CNS) (see Chapter 42), and acute glomerulonephritis (AGN), an acute kidney infection (see Chapter 44). Permanent damage can result from these sequelae, especially RF. GABHS may also cause skin manifestations, including impetigo and pyoderma. Group A β-hemolytic streptococci infection is generally a relatively brief illness that varies in severity from subclinical (no symptoms) to severe toxicity. The onset is often abrupt and characterized by pharyngitis, headache, fever, and abdominal pain. The tonsils and pharynx may be inflamed and covered with exudate (Fig. 40-1), which usually appears by the second day of illness. However, streptococcal infections should be suspected in children older than 2 years who have pharyngitis without exudate or nasal symptoms. The tongue may appear edematous and red (strawberry tongue), and the child may have a fine sandpaper rash on the trunk, axillae, elbows, and groin seen in scarlet fever (caused by a strain of group A streptococcus). The uvula is edematous and red. Anterior cervical lymphadenopathy (in ≈30% to 50% of cases) usually occurs early, and the nodes are often tender. Pain can be relatively mild to severe enough to make swallowing difficult. Clinical manifestations usually subside in 3 to 5 days unless complicated by sinusitis or parapharyngeal, peritonsillar, or retropharyngeal abscess. Nonsuppurative complications may appear after the onset of GABHS—AGN in about 10 days and RF in an average of 18 days. Children who are GABHS carriers may have a positive throat culture but often experience a coincidental viral illness. Although antibiotic administration is not indicated for most GABHS carriers, some conditions require antibiotic therapy; these are published in the AAP’s Red Book (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] Committee on Infectious Diseases, 2012). Rapid identification of GABHS with diagnostic test kits (rapid antigen detection test) is possible in the office or clinic setting. Because of the high specificity of these rapid tests, a positive test result generally does not require throat culture confirmation. However, the sensitivities of these kits vary considerably and a confirmatory throat culture is recommended in patients who have a negative test result (AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, 2012). Intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G is an appropriate therapy, but it is painful and is not the first choice for children. Oral erythromycin is indicated for children who are allergic to penicillin. Other antibiotics used to treat GABHS are azithromycin, clarithromycin, oral cephalosporins, amoxicillin, and amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, 2012; Wessels, 2011).

Respiratory Dysfunction

Care Management

Promote Hydration.

Provide Nutrition.

Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

Nasopharyngitis

Therapeutic Management

Care Management

Acute Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnostic Evaluation

Therapeutic Management

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Respiratory Dysfunction

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access