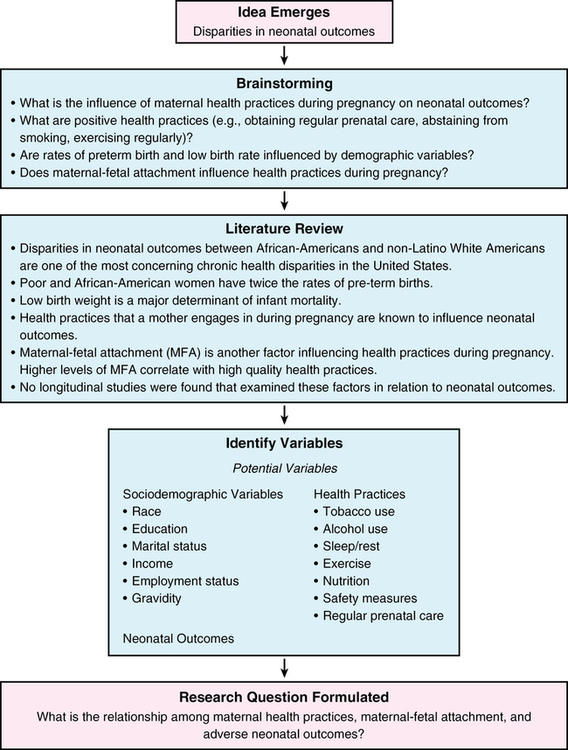

CHAPTER 2 After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: • Describe how the research question and hypothesis relate to the other components of the research process. • Describe the process of identifying and refining a research question or hypothesis. • Discuss the appropriate use of research questions versus hypotheses in a research study. • Identify the criteria for determining the significance of a research question or hypothesis. • Discuss how the purpose, research question, and hypothesis suggest the level of evidence to be obtained from the findings of a research study. • Discuss the purpose of developing a clinical question. • Discuss the differences between a research question and a clinical question in relation to evidence-based practice. • Apply critiquing criteria to the evaluation of a research question and hypothesis in a research report. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critiquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. At the beginning of this chapter you will learn about research questions and hypotheses from the perspective of the researcher, which, in the second part of this chapter, will help you to generate your own clinical questions that you will use to guide the development of evidence-based practice projects. From a clinician’s perspective, you must understand the research question and hypothesis as it aligns with the rest of a study. As a practicing nurse, the clinical questions you will develop (see Chapters 19, 20, and 21) represent the first step of the evidence-based practice process for quality improvement programs such as those that decrease risk for development of decubitus ulcers. Hypotheses can be considered intelligent hunches, guesses, or predictions that help researchers seek a solution or answer a research question. Hypotheses are a vehicle for testing the validity of the theoretical framework assumptions, and provide a bridge between theory (a set of interrelated concepts, definitions, and propositions) and the real world (see Chapter 4). A researcher spends a great deal of time refining a research idea into a testable research question. Research questions or topics are not pulled from thin air. As shown in Table 2-1, research questions should indicate that practical experience, critical appraisal of the scientific literature, or interest in an untested theory was the basis for the generation of a research idea. The research question should reflect a refinement of the researcher’s initial thinking. The evaluator of a research study should be able to discern that the researcher has done the following: TABLE 2-1 HOW PRACTICAL EXPERIENCE, SCIENTIFIC LITERATURE, AND UNTESTED THEORY INFLUENCE THE DEVELOPMENT OF A RESEARCH IDEA • Defined a specific question area • Reviewed the relevant literature • Examined the question’s potential significance to nursing • Pragmatically examined the feasibility of studying the research question Brainstorming with faculty or colleagues may provide valuable feedback that helps the researcher focus on a specific research question area. For example, suppose a researcher told a colleague that her area of interest was health disparities and how neonatal outcomes vary in ethnic minority, urban, and low-income populations. The colleague may have asked, “What is it about the topic that specifically interests you?” This conversation may have initiated a chain of thought that resulted in a decision to explore the relationship between maternal-fetal attachment and health practices on neonatal outcomes in low-income, urban women (Alhusen et al., 2012) (see Appendix B). Figure 2-1 illustrates how a broad area of interest (health disparities and neonatal outcomes) was narrowed to a specific research topic (maternal-fetal attachment and health practices on neonatal outcomes in low-income, urban women). The literature review should reveal a relevant collection of studies and systematic reviews that have been critically examined. Concluding sections in such articles (i.e., the recommendations and implications for practice) often identify remaining gaps in the literature, the need for replication, or the need for extension of the knowledge base about a particular research focus (see Chapter 3). In the previous example about the influence of maternal-fetal attachment and health practices on neonatal outcomes in low-income, urban women, the researcher may have conducted a preliminary review of books and journals for theories and research studies on factors apparently critical to adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as pre-term birth and low birth weight and racial and/or ethnic differences in neonatal outcomes. These factors, called variables, should be potentially relevant, of interest, and measurable. Possible relevant factors mentioned in the literature begin with an exploration of the relationship between maternal health practices during pregnancy, and neonatal outcomes. Another factor, maternal-fetal attachment, has been found to correlate with these high quality health practices. Other variables, called demographic variables, such as race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, education, and marital status, are also suggested as essential to consider. For example, are rates of pre-term birth and growth-restricted neonates higher in low-income women than in other women? This information can then be used to further define the research question and address a gap in the literature, as well as to extend the knowledge base related to relationships among maternal health practices, maternal-fetal attachment, race (black or white), and socio-economic status. At this point the researcher could write the tentative research question: “What are the relationships among maternal health practices, maternal-fetal attachment, and adverse neonatal outcomes?” Readers can envision the interrelatedness of the initial definition of the question area, the literature review, and the refined research question. Readers of research reports examine the end product of this process in the form of a research question and/or hypothesis, so it is important to have an appreciation of how the researcher gets to that point in constructing a study (Alhusen et al., 2012) (see Appendix B). • Patients, nurses, the medical community in general, and society will potentially benefit from the knowledge derived from the study. • Results will be applicable for nursing practice, education, or administration. • Results will be theoretically relevant. • Findings will lend support to untested theoretical assumptions, extend or challenge an existing theory, fill a gap, or clarify a conflict in the literature. • Findings will potentially provide evidence that supports developing, retaining, or revising nursing practices or policies. • Disparities in neonatal outcomes between African Americans and non-Latino white Americans are one of the most concerning chronic health disparities in the United States. • Poor and African-American women have twice the rates of pre-term births. • Low birth weight is a major determinant of infant mortality. • Health practices that a mother engages in during pregnancy are known to influence neonatal outcomes. • Maternal-fetal attachment (MFA) is another factor influencing health practices during pregnancy. Higher levels of MFA correlate with high quality health practices. • No longitudinal studies were found that examined these factors in relation to neonatal outcomes. • This study also sought to fill a gap in the related literature by extending research to focus on low income and ethnic minority women. The feasibility of a research question must be pragmatically examined. Regardless of how significant or researchable a question may be, pragmatic considerations such as time; availability of subjects, facilities, equipment, and money; experience of the researcher; and any ethical considerations may cause the researcher to decide that the question is inappropriate because it lacks feasibility (see Chapters 4 and 8). When a researcher finalizes a research question, the following characteristics should be evident: • It clearly identifies the variables under consideration. • It specifies the population being studied. An independent variable, usually symbolized by X, is the variable that has the presumed effect on the dependent variable. In experimental research studies, the researcher manipulates the independent variable (see Chapter 9). In nonexperimental research, the independent variable is not manipulated and is assumed to have occurred naturally before or during the study (see Chapter 10). Table 2-2 presents a number of examples of research questions. Practice substituting other variables for the examples in Table 2-2. You will be surprised at the skill you develop in writing and critiquing research questions with greater ease. TABLE 2-2 The population (a well-defined set that has certain properties) is either specified or implied in the research question. If the scope of the question has been narrowed to a specific focus and the variables have been clearly identified, the nature of the population will be evident to the reader of a research report. For example, a research question may ask, “Does an association exist among health literacy, memory performance, and performance-based functional ability in community-residing older adults?” This question suggests that the population under consideration includes community-residing older adults. It is also implied that the community-residing older adults were screened for cognitive impairment and presence of dementia, were divided into groups (impaired or normal), and participated in a memory training intervention or a health training intervention to determine its effect on affective and cognitive outcomes (McDougall et al., 2012). The researcher or reader will have an initial idea of the composition of the study population from the outset (see Chapter 12).

Research questions, hypotheses, and clinical questions

Developing and refining a research question: Study perspective

AREA

INFLUENCE

EXAMPLE

Practical Experience

Clinical practice provides a wealth of experience from which research problems can be derived. The nurse may observe a particular event or pattern and become curious about why it occurs, as well as its relationship to other factors in the patient’s environment.

Health professionals, including nurses and nurse midwives, frequently debate the benefit of psychological follow-up in preventing or reducing anxiety and depression following miscarriage. While such symptoms may be part of their grief following the loss, psychological follow-up might detect those women at risk for complications such as suicide. Evidence about physical management of women following miscarriage is well established, evidence on the psychological management is less well developed and represents a gap in the literature. Findings from a systematic review, “Follow-up for Improving Psychological Well-being for Women after a Miscarriage,” that included six studies including >1000 women indicate there is insufficient evidence from randomized controlled trials to recommend any method of psychological follow-up (Murphy et al., 2012).

Critical Appraisal of the Scientific Literature

Critical appraisal of studies in journals may indirectly suggest a clinical problem by stimulating the reader’s thinking. The nurse may observe the outcome data from a single study or a group of related studies that provide the basis for developing a pilot study, quality improvement project, or clinical practice guideline to determine the effectiveness of this intervention in their setting.

At a staff meeting, members of an interprofessional team at a hospital specializing in cancer treatment wanted to identify the most effective approaches for treating adult cancer pain by decreasing attitudinal barriers of patients to cancer pain management. Their search for, and critical appraisal of, existing research studies led the team to develop an interprofessional cancer pain guideline that was relevant to their patient population and clinical setting (MD Anderson Cancer Center, 2012).

Gaps in the Literature

A research idea may also be suggested by a critical appraisal of the literature that identifies gaps in the literature and suggests areas for future study. Research ideas also can be generated by research reports that suggest the value of replicating a particular study to extend or refine the existing scientific knowledge base.

Although advances in pain management can reduce cancer pain for a significant number of patients, attitudinal barriers held by patients can be a significant factor in the inadequate treatment of cancer pain. Those barriers need to be addressed if cancer pain management is to be improved. The majority of studies investigating the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions were either not applicable in outpatient settings, or were labor intensive and not very feasible. However, use of motivational interviewing as a coaching intervention in decreasing patient attitudinal barriers to pain management had not been investigated, especially in an outpatient setting. The study focused on testing the effectiveness of an educational and a motivational interviewing coaching intervention in comparison to usual care in decreasing attitudinal barriers to cancer pain management, decreasing pain intensity, improving functional status, and improving quality of life (Thomas et al., 2012).

Interest in Untested Theory

Verification of a theory and its concepts provides a relatively uncharted area from which research problems can be derived. Inasmuch as theories themselves are not tested, a researcher may consider investigating a concept or set of concepts related to a nursing theory or a theory from another discipline. The researcher would pose questions like, “If this theory is correct, what kind of behavior would I expect to observe in particular patients and under which conditions?” “If this theory is valid, what kind of supporting evidence will I find?”

The Roy Adaptation Model (RAM) (2009) was used by Fawcett and colleagues (2012) in a study examining womens’ perceptions of Caesarean birth to test multiple relationships within the RAM as applied to the study population.

Defining the research question

Beginning the literature review

Examining significance

Determining feasibility

The fully developed research question

Variables

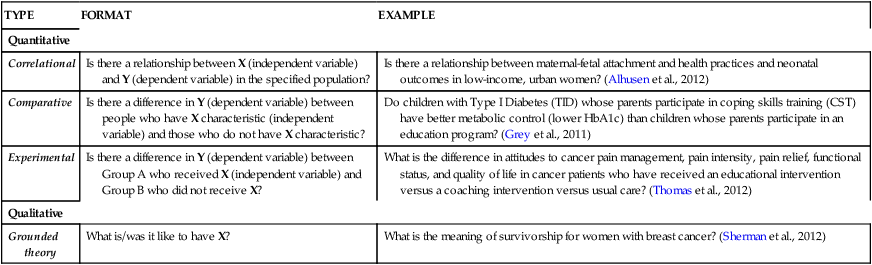

TYPE

FORMAT

EXAMPLE

Quantitative

Correlational

Is there a relationship between X (independent variable) and Y (dependent variable) in the specified population?

Is there a relationship between maternal-fetal attachment and health practices and neonatal outcomes in low-income, urban women? (Alhusen et al., 2012)

Comparative

Is there a difference in Y (dependent variable) between people who have X characteristic (independent variable) and those who do not have X characteristic?

Do children with Type I Diabetes (TID) whose parents participate in coping skills training (CST) have better metabolic control (lower HbA1c) than children whose parents participate in an education program? (Grey et al., 2011)

Experimental

Is there a difference in Y (dependent variable) between Group A who received X (independent variable) and Group B who did not receive X?

What is the difference in attitudes to cancer pain management, pain intensity, pain relief, functional status, and quality of life in cancer patients who have received an educational intervention versus a coaching intervention versus usual care? (Thomas et al., 2012)

Qualitative

Grounded theory

What is/was it like to have X?

What is the meaning of survivorship for women with breast cancer? (Sherman et al., 2012)

Population

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Research questions, hypotheses, and clinical questions

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access