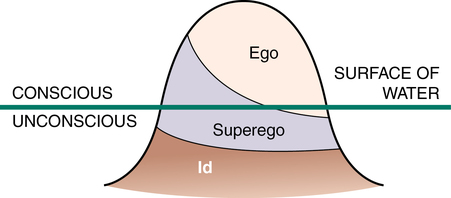

CHAPTER 2 1. Evaluate the premises behind the various therapeutic models discussed in this chapter. 2. Describe the evolution of therapies for psychiatric disorders. 3. Identify ways each theorist contributes to the nurse’s ability to assess a patient’s behaviors. 4. Provide responses to the following based on clinical experience: a. An example of how a patient’s irrational beliefs influenced behavior. b. An example of countertransference in your relationship with a patient. c. An example of the use of behavior modification with a patient. 5. Identify Peplau’s framework for the nurse-patient relationship. 6. Choose the therapeutic model that would be most useful for a particular patient or patient problem. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis As part his treatment, Freud initially used hypnosis, but this provided mixed therapeutic results. He then changed his approach to talk therapy, known as the cathartic method. Today, we refer to catharsis as “getting things off our chests.” Talk therapy evolved to include “free association,” which requires full and honest disclosure of thoughts and feelings as they come to mind. Dream analysis became an essential part of his therapy since Freud believed that urges and impulses of the unconscious mind were symbolically played out in dreams. Freud (1961, 1969) concluded that talking about difficult emotional issues had the potential to heal the wounds causing mental illness. Viewing the success of these therapeutic approaches led Freud to construct his psychoanalytic theory. Through the use of talk therapy and free association, Freud came to the conclusion that there were three levels of psychological awareness in operation. He offered a topographic theory of how the mind functions, a description of the landscape of the mind. He used the image of an iceberg to describe these levels of awareness (Figure 2-1). Freud (1969) believed that anxiety is an inevitable part of living. The environment in which we live presents dangers and insecurities, threats and satisfactions. It can produce pain and increase tension or produce pleasure and decrease tension. The ego develops defenses, or defense mechanisms, to ward off anxiety by preventing conscious awareness of threatening feelings. Defense mechanisms share two common features: (1) they all (except suppression) operate on an unconscious level and (2) they deny, falsify, or distort reality to make it less threatening. Although we cannot survive without defense mechanisms, it is possible for our defense mechanisms to distort reality to such a degree that we experience difficulty with healthy adjustment and personal growth. Chapter 12 offers further discussions of defense mechanisms. Freud believed that human development proceeds through five stages from infancy to adulthood. His main focus, however, was on events that occur during the first 5 years of life. From Freud’s perspective, experiences during the early stages determined an individual’s lifetime adjustment patterns and personality traits. In fact, Freud thought that personality was formed by the time the child entered school and that subsequent growth consisted of elaborating on this basic structure. Freud’s psychosexual stages of development are presented in Table 2-1. TABLE 2-1 FREUD’S PSYCHOSEXUAL STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT Data from Gleitman, H. (1981). Psychology. New York, NY: W. W. Norton. Classical psychoanalysis, as developed by Sigmund Freud, is seldom used today. Freud’s premise that all mental illness is caused by early intrapsychic conflict is no longer widely thought to be valid, and such therapy requires an unrealistically lengthy period of treatment (i.e., three to five times a week for nearly six years), making it prohibitively expensive and not insured for most. There are two concepts from classic psychoanalysis that are important for nurses to know: transference and countertransference (Freud, 1969). Transference refers to feelings that the patient has toward health care workers that were originally held toward significant others in his or her life. When transference occurs, these feelings become available for exploration with the patient. Such exploration helps the patient to better understand certain feelings and behaviors. Countertransference refers to unconscious feelings that the health care worker has toward the patient. For instance, if the patient reminds you of someone you do not like, you may unconsciously react as if the patient were that individual. Countertransference underscores the importance of maintaining self-awareness and seeking supervisory guidance as therapeutic relationships progress. Chapter 10 talks more about countertransference and the nurse-patient relationship. Psychodynamic therapy follows the psychoanalytic model by using many of the tools of psychoanalysis, such as free association, dream analysis, transference, and countertransference; however, the therapist has increased involvement and interacts with the patient more freely than in traditional psychoanalysis. The therapy is oriented more to the here and now and makes less of an attempt to reconstruct the developmental origins of conflicts (Dewan, Steenbarger, & Greenberg, 2011). Psychodynamic therapy tends to last longer than other common therapeutic modalities and may extend for more than 20 sessions, which insurance companies often reject. Brief therapies share the following common elements: • The central focus is established early, usually during the first session or two. • Clear expectations are established for time-limited therapy with improvement demonstrated within a small number of sessions. • Goals are concrete, and there is one major focus on improving the patient’s worst symptoms, improving coping skills, and helping the patient understand what is going on in his or her life. • Interpretations are directed toward present-life circumstances and patient behavior rather than toward the historical significance of feelings. • There is a general understanding that psychotherapy does not cure but that it can help troubled individuals learn to better deal with life’s inevitable stressors. Erik Erikson (1902-1994), an American psychoanalyst, was also a follower of Freud; however, Erikson (1963) believed that Freudian theory was restrictive and negative in its approach. He also stressed that an individual’s development is influenced by more than the limited mother-child-father triangle and that culture and society exert significant influence on personality. According to Erikson, personality was not set in stone at age 5, as Freud suggested, but continued to develop throughout the life span. Erikson described development as occurring in eight predetermined and consecutive life stages (psychosocial crises), each of which consists of two possible outcomes (e.g., industry vs. inferiority). The successful or unsuccessful completion of each stage will affect the individual’s progression to the next (Table 2-2). For example, Erikson’s crisis of industry versus inferiority occurs from the ages of 7 to 12. During this stage, the child’s task is to gain a sense of personal abilities and competence and to expand relationships beyond the immediate family to include peers. The attainment of this task (industry) brings with it the virtue of confidence. The child who fails to navigate this stage successfully is unable to master age-appropriate tasks, cannot make a connection with peers, and will feel like a failure (inferiority). TABLE 2-2 ERIKSON’S EIGHT STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT Data from Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society. New York, NY: W. W. Norton; Altrocchi, J. (1980). Abnormal psychology (p. 196). New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Harry Stack Sullivan (1892-1949), an American-born psychiatrist, initially approached patients from a Freudian framework, but he became frustrated by dealing with what he considered unseen and private mental processes within the individual. He turned his attention to interpersonal processes that could be observed in a social framework. Sullivan (1953) defined personality as behavior that can be observed within interpersonal relationships. This premise led to the development of his interpersonal theory. Interpersonal psychotherapy is an effective short-term therapy derived from the school of psychiatry that originated with Adolph Meyer and Harry Stack Sullivan. The assumption is that psychiatric disorders are influenced by interpersonal interactions and the social context. The goal of interpersonal psychotherapy is to reduce or eliminate psychiatric symptoms (particularly depression) by improving interpersonal functioning and satisfaction with social relationships (Dewan, Steenbarger, & Greenberger, 2011). Interpersonal psychotherapy has proved successful in the treatment of depression. Treatment is predicated on the notion that disturbances in important interpersonal relationships (or a deficit in one’s capacity to form those relationships) can play a role in initiating or maintaining clinical depression. In interpersonal psychotherapy, the therapist identifies the nature of the problem to be resolved and then selects strategies consistent with that problem area. Four types of problem areas have been identified (Hollon & Engelhardt, 1997): Hildegard Peplau (1909-1999) (Figure 2-2), influenced by the work of Sullivan and learning theory, developed the first systematic theoretical framework for psychiatric nursing in her groundbreaking book Interpersonal Relations in Nursing (1952). Peplau not only established the foundation for the professional practice of psychiatric nursing but also continued to enrich psychiatric nursing theory and work for the advancement of nursing practice throughout her career.

Relevant theories and therapies for nursing practice

Psychoanalytic theories and therapies

Sigmund freud’s psychoanalytic theory

Levels of awareness

Defense mechanisms and anxiety

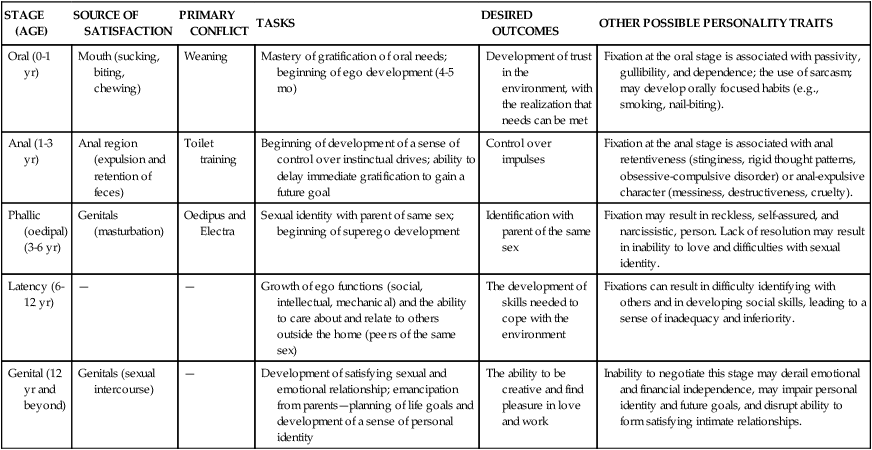

Psychosexual stages of development

STAGE (AGE)

SOURCE OF SATISFACTION

PRIMARY CONFLICT

TASKS

DESIRED OUTCOMES

OTHER POSSIBLE PERSONALITY TRAITS

Oral (0-1 yr)

Mouth (sucking, biting, chewing)

Weaning

Mastery of gratification of oral needs; beginning of ego development (4-5 mo)

Development of trust in the environment, with the realization that needs can be met

Fixation at the oral stage is associated with passivity, gullibility, and dependence; the use of sarcasm; may develop orally focused habits (e.g., smoking, nail-biting).

Anal (1-3 yr)

Anal region (expulsion and retention of feces)

Toilet training

Beginning of development of a sense of control over instinctual drives; ability to delay immediate gratification to gain a future goal

Control over impulses

Fixation at the anal stage is associated with anal retentiveness (stinginess, rigid thought patterns, obsessive-compulsive disorder) or anal-expulsive character (messiness, destructiveness, cruelty).

Phallic (oedipal) (3-6 yr)

Genitals (masturbation)

Oedipus and Electra

Sexual identity with parent of same sex; beginning of superego development

Identification with parent of the same sex

Fixation may result in reckless, self-assured, and narcissistic, person. Lack of resolution may result in inability to love and difficulties with sexual identity.

Latency (6-12 yr)

—

—

Growth of ego functions (social, intellectual, mechanical) and the ability to care about and relate to others outside the home (peers of the same sex)

The development of skills needed to cope with the environment

Fixations can result in difficulty identifying with others and in developing social skills, leading to a sense of inadequacy and inferiority.

Genital (12 yr and beyond)

Genitals (sexual intercourse)

—

Development of satisfying sexual and emotional relationship; emancipation from parents—planning of life goals and development of a sense of personal identity

The ability to be creative and find pleasure in love and work

Inability to negotiate this stage may derail emotional and financial independence, may impair personal identity and future goals, and disrupt ability to form satisfying intimate relationships.

Classical psychoanalysis

Psychodynamic therapy

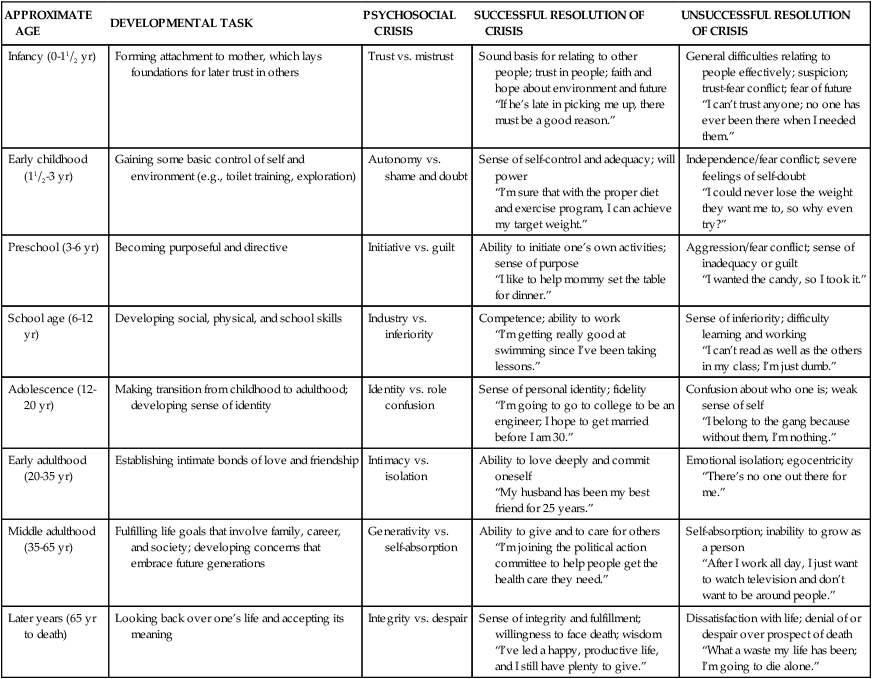

Erik erikson’s ego theory

APPROXIMATE AGE

DEVELOPMENTAL TASK

PSYCHOSOCIAL CRISIS

SUCCESSFUL RESOLUTION OF CRISIS

UNSUCCESSFUL RESOLUTION OF CRISIS

Infancy (0-11/2 yr)

Forming attachment to mother, which lays foundations for later trust in others

Trust vs. mistrust

Sound basis for relating to other people; trust in people; faith and hope about environment and future

“If he’s late in picking me up, there must be a good reason.”

General difficulties relating to people effectively; suspicion; trust-fear conflict; fear of future

“I can’t trust anyone; no one has ever been there when I needed them.”

Early childhood (11/2-3 yr)

Gaining some basic control of self and environment (e.g., toilet training, exploration)

Autonomy vs. shame and doubt

Sense of self-control and adequacy; will power

“I’m sure that with the proper diet and exercise program, I can achieve my target weight.”

Independence/fear conflict; severe feelings of self-doubt

“I could never lose the weight they want me to, so why even try?”

Preschool (3-6 yr)

Becoming purposeful and directive

Initiative vs. guilt

Ability to initiate one’s own activities; sense of purpose

“I like to help mommy set the table for dinner.”

Aggression/fear conflict; sense of inadequacy or guilt

“I wanted the candy, so I took it.”

School age (6-12 yr)

Developing social, physical, and school skills

Industry vs. inferiority

Competence; ability to work

“I’m getting really good at swimming since I’ve been taking lessons.”

Sense of inferiority; difficulty learning and working

“I can’t read as well as the others in my class; I’m just dumb.”

Adolescence (12-20 yr)

Making transition from childhood to adulthood; developing sense of identity

Identity vs. role confusion

Sense of personal identity; fidelity

“I’m going to go to college to be an engineer; I hope to get married before I am 30.”

Confusion about who one is; weak sense of self

“I belong to the gang because without them, I’m nothing.”

Early adulthood (20-35 yr)

Establishing intimate bonds of love and friendship

Intimacy vs. isolation

Ability to love deeply and commit oneself

“My husband has been my best friend for 25 years.”

Emotional isolation; egocentricity

“There’s no one out there for me.”

Middle adulthood (35-65 yr)

Fulfilling life goals that involve family, career, and society; developing concerns that embrace future generations

Generativity vs. self-absorption

Ability to give and to care for others

“I’m joining the political action committee to help people get the health care they need.”

Self-absorption; inability to grow as a person

“After I work all day, I just want to watch television and don’t want to be around people.”

Later years (65 yr to death)

Looking back over one’s life and accepting its meaning

Integrity vs. despair

Sense of integrity and fulfillment; willingness to face death; wisdom

“I’ve led a happy, productive life, and I still have plenty to give.”

Dissatisfaction with life; denial of or despair over prospect of death

“What a waste my life has been; I’m going to die alone.”

Interpersonal theories and therapies

Harry stack sullivan’s interpersonal theory

Interpersonal psychotherapy

Hildegard peplau’s theory of interpersonal relationships in nursing

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Relevant theories and therapies for nursing practice

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access