CHAPTER 21 Maja Djukic and Mattia J. Gilmartin • Discuss the characteristics of quality health care defined by the Institute of Medicine. • Compare the characteristics of the major quality improvement (QI) models used in health care. • Identify two databases used to report health care organization’s performance to promote consumer choice and guide clinical QI activities. • Describe the relationship between nursing-sensitive quality indicators and patient outcomes. • Describe the steps in the improvement process and determine appropriate QI tools to use in each phase of the improvement process. • List four themes for improvement to apply to the unit where you work. • Describe ways that nurses can lead QI projects in clinical settings. • Use the SQUIRE Guidelines to critique a journal article reporting the results of a QI project. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critiquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. The Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2001) defines quality health care as care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable (Box 21-1). The quality of the health care system was brought to the forefront of national attention in several important reports (IOM, 1999; 2001), including Crossing the Quality Chasm, which concluded that “between the health care we have and the care we could have lies not just a gap, but a chasm” (IOM, 2001, p. 1). The report notes that “the performance of the health care system varies considerably. It may be exemplary, but often is not, and millions of Americans fail to receive effective care” (IOM, 2001, p. 3). The first national report card on U.S. health care quality (McGlynn et al., 2003) identified that adults, regardless of their race, gender, or financial status, receive only about half of the recommended care for leading causes of death and disability such as pneumonia, diabetes, asthma, and coronary artery disease. Quality of care has improved for some conditions (Chassin et al., 2010). For example, prophylactic antibiotic administration within 1 hour of starting a surgical incision is now a recommended practice. In 2002, only about 10% of hospitals were in compliance with this practice, but in 2009 about 90% of hospitals reported being in compliance. Still, much room for improvement of quality remains, as evident from the latest report of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 2012). The report concluded that health care effectiveness, patient safety, timeliness, patient centeredness, care coordination, efficiency, health system infrastructure, and access are suboptimal, especially for minority and low-income groups. For example, fewer than 25% of adults age 40 years and older with diabetes receive all four recommended interventions (Hemoglobin A1c tests, foot exam, dilated eye exam, and flu shot) (AHRQ, 2012). Also, almost 20% of adults report sometimes or never receiving care as soon as they want it, even if they need care right away for an illness, injury, or condition (AHRQ, 2012). Despite these quality issues, the U.S. spends twice as much on health care per capita per year at $7,290, compared with other developed nations, while ranking last in health care quality (Davis et al., 2010). The purpose of this chapter is to introduce you to the principles of quality improvement (QI) and provide examples of how to apply these principles in your practice so you can effectively contribute to needed health care improvements. QI “uses data to monitor the outcomes of care processes and improvement methods to design and test changes to continuously improve the quality and safety of health care systems” (Cronenwett et al., 2007, p. 127). Florence Nightingale championed QI by systematically documenting high rates of morbidity and mortality resulting from poor sanitary conditions among soldiers serving in the Crimean War of 1854 (Henry et al., 1992). She used statistics to document changes in soldiers’ health, including reductions in mortality resulting from a number of nursing interventions such as hand hygiene, instrument sterilization, changing of bed linens, ward sanitation, ventilation, and proper nutrition (Henry et al., 1992). Today, nurses continue to be vital to health system improvement efforts (IOM, 2011). One main initiative developed to bolster nurses’ education in health system improvements is Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) (Cronenwett et al., 2007). The overall goal of this project is to help build nurses’ competence in the areas of QI, patient-centered care, teamwork and collaboration, patient safety, informatics, and evidence-based practice (EBP). Other initiatives, including Transforming Care at the Bedside (TCAB), Integrated Nurse Leadership Program, and the Clinical Scene Investigator Academy have been developed to increase nurses’ engagement in QI (Kliger et al., 2010). To effectively influence improvements in the work setting and ensure that all patients consistently receive excellent care, it is important to The first National Quality Strategy (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2012a) established aims and priorities for QI (Box 21-2). Achieving these national quality targets requires major redesign of the health care system. One way you can contribute to this redesign is to familiarize yourself with the national priorities, improvement targets, and corresponding national initiatives (described in Table 21-1) and use them to guide improvements in your work setting. TABLE 21-1 NATIONAL QUALITY STRATEGY PRIORITIES, IMPROVEMENT TARGETS, AND RELATED INITIATIVES • Patients are asked if staff took patient and family’s preferences into account in deciding what health care needs would be when discharged • When discharged, was there a good understanding of what patient and family were responsible for in managing their health • When discharged patient clearly understood purpose for taking medications From the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2012a). National strategy for quality improvement in health care. Retrieved from www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/nqs/nqs2012annlrpt.pdf QI relies on aligning institutional priorities with external incentives that drive QI, including accreditation, financial incentives, performance measurement, and public reporting (Ferlie & Shortell, 2001). Accreditation is a process in which an organization demonstrates attainment of predetermined standards set by an external nongovernmental organization responsible for setting and monitoring compliance in a particular industry sector (Scrivens, 1997). Several accrediting bodies are listed in Box 21-3. Financial incentives seek to align providers’ behaviors with improvements in the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of health care services by paying a bonus to individuals and organizations that deliver care within a set budget or meet preestablished performance targets (Rosenthal & Frank, 2006). Box 21-4 on p. 448 shows examples of financial incentives. Performance measurement is a tool that tracks an organization’s performance using standardized measures to document and manage quality. National health care performance standards are developed using a consensus process in which stakeholder groups, representing the interests of the public, health professionals, payers, employers, and government identify priorities, measures, and reporting requirements to document and manage the quality of care (National Quality Forum [NQF], 2004). See Box 21-5 on p. 449 for examples of groups responsible for developing measurement standards. Public reporting provides objective information to promote consumer choice, guide QI efforts, and promote accountability for performance among providers and delivery organizations. It also allows organizations to compare their performance across standard measures against their peer organizations locally and nationally (Giordano et al., 2010). Several major public reporting systems are described in Box 21-6 on p. 449. Nurses deliver the majority of health care and therefore have a substantial influence on its overall quality (IOM, 2011). However, nursing’s contribution to the overall quality of health care has been difficult to quantify, owing in part to insufficient standardized measurement systems capable of capturing nursing care contribution to patient outcomes. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has funded the NQF to recommend nursing-sensitive consensus standards to be used to set standards for public accountability and QI. The work of the NQF (2004) resulted in endorsement of 15 nursing-sensitive quality indicators (Table 21-2 on p. 450). Since the endorsement of “NQF 15,” several data reporting mechanisms have been established for performance sharing internally among providers to identify areas in need of improvement, externally for purposes of accreditation and payment, and with health care consumers so that they can choose providers based on the quality of services provided. Examples include Hospital Compare (USDHHS, 2012b) and the nursing-specific databases described by Alexander (2007): TABLE 21-2 NATIONAL VOLUNTARY STANDARDS FOR NURSING-SENSITIVE CARE • Percent of RN care hours to total nursing care hours. • Percent of LVN/LPN care hours to total nursing care hours. • Percent of UAP care hours to total nursing care hours • Percent of contract hours (RN, LVN/LPN, and UAP) to total nursing care hours. • Nurse participation in hospital affairs. • Nursing foundations for quality of care. • Nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses. • Staffing and resource adequacy. *Note.() indicates NQF-endorsed national voluntary consensus standard for hospital care. Reproduced with permission from National Quality Forum. (2012). Measuring performance. Retrieved from www.qualityforum.org/Measuring_Performance/ABCs_of_Measurement.aspx • The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators® is a proprietary database of the American Nurses Association. The database collects and evaluates unit-specific nurse-sensitive data from hospitals in the U.S. Participating facilities receive unit-level comparative data reports to use for QI purposes. • California Nursing Outcomes Coalition (CalNOC) is a data repository of hospital-generated, unit-level, acute nurse staffing and workforce characteristics and processes of care, as well as key NQF-endorsed, nursing-sensitive outcome measures, submitted electronically via the web. • Veterans Affairs Nursing Outcomes Database was originally modeled after CalNOC. Data are collected at the unit and hospital levels to facilitate evaluation of quality and enable benchmarking within and among Veterans Affairs facilities. Measurement of quality indicators must be done methodically using standardized tools. Standardized measurement allows for benchmarking, which is “a systematic approach for gathering information about process or product performance and then analyzing why and how performance differs between business units” (Massoud et al., 2001, p. 74). Benchmarking is critical for QI because it helps identify when performance is below an agreed-upon standard, and it signals the need for improvement. For example, when you record assessment of your patient’s skin status using a standardized assessment tool such as the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Score Risk (Stotts & Gunningberg, 2007), it allows for comparison of your assessment to those of providers in other organizations who provide care to a similar patient population and who use the same tool to document assessments. Tracking changes in the overall Braden Scale score over time allows you to intervene, if the score falls below a set standard, indicating high risk for pressure ulcer development. Equally, after you implement needed interventions such as changes in feeding or mobility, you can track changes in the Braden Scale score to determine whether the interventions were effective in reducing risk for pressure ulcer development. Therefore, standardized measurement can tell you when changes in care are needed and whether implemented interventions have resulted in actual improvement of patient outcomes. When all clinical units document care in the same way, it is possible to document pressure ulcer care across units. These performance data are useful for benchmarking efforts where clinical teams learn from each other how to apply best practices from high-performing units to the care processes of lower-performing units. Benchmarking (Massoud et al., 2001, p. 75) can be used to

Quality improvement

Nurses’ role in health care QI

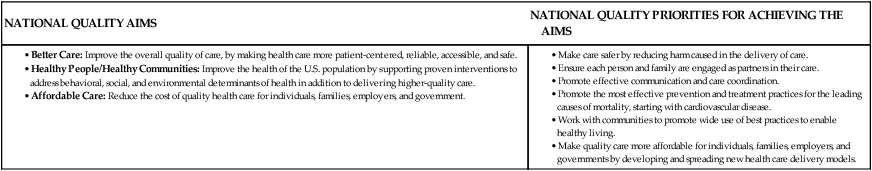

National goals and strategies for health care QI

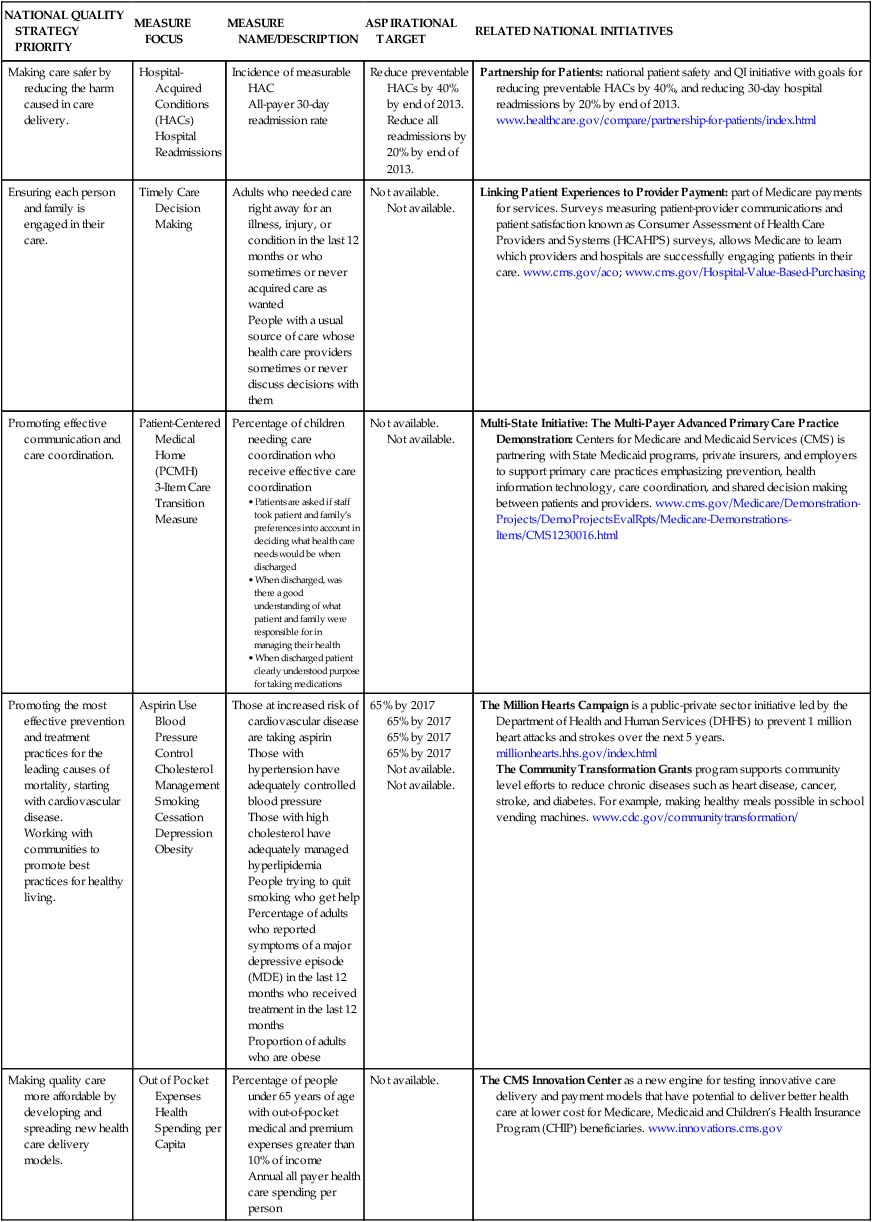

NATIONAL QUALITY STRATEGY PRIORITY

MEASURE FOCUS

MEASURE NAME/DESCRIPTION

ASPIRATIONAL TARGET

RELATED NATIONAL INITIATIVES

Making care safer by reducing the harm caused in care delivery.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions (HACs)

Hospital Readmissions

Incidence of measurable HAC

All-payer 30-day readmission rate

Reduce preventable HACs by 40% by end of 2013.

Reduce all readmissions by 20% by end of 2013.

Partnership for Patients: national patient safety and QI initiative with goals for reducing preventable HACs by 40%, and reducing 30-day hospital readmissions by 20% by end of 2013. www.healthcare.gov/compare/partnership-for-patients/index.html

Ensuring each person and family is engaged in their care.

Timely Care

Decision Making

Adults who needed care right away for an illness, injury, or condition in the last 12 months or who sometimes or never acquired care as wanted

People with a usual source of care whose health care providers sometimes or never discuss decisions with them

Not available.

Not available.

Linking Patient Experiences to Provider Payment: part of Medicare payments for services. Surveys measuring patient-provider communications and patient satisfaction known as Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) surveys, allows Medicare to learn which providers and hospitals are successfully engaging patients in their care. www.cms.gov/aco; www.cms.gov/Hospital-Value-Based-Purchasing

Promoting effective communication and care coordination.

Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH)

3-Item Care Transition Measure

Percentage of children needing care coordination who receive effective care coordination

Not available.

Not available.

Multi-State Initiative: The Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is partnering with State Medicaid programs, private insurers, and employers to support primary care practices emphasizing prevention, health information technology, care coordination, and shared decision making between patients and providers. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Demonstration-Projects/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/Medicare-Demonstrations-Items/CMS1230016.html

Promoting the most effective prevention and treatment practices for the leading causes of mortality, starting with cardiovascular disease.

Working with communities to promote best practices for healthy living.

Aspirin Use

Blood Pressure Control

Cholesterol Management

Smoking Cessation

Depression

Obesity

Those at increased risk of cardiovascular disease are taking aspirin

Those with hypertension have adequately controlled blood pressure

Those with high cholesterol have adequately managed hyperlipidemia

People trying to quit smoking who get help

Percentage of adults who reported symptoms of a major depressive episode (MDE) in the last 12 months who received treatment in the last 12 months

Proportion of adults who are obese

65% by 2017

65% by 2017

65% by 2017

65% by 2017

Not available.

Not available.

The Million Hearts Campaign is a public-private sector initiative led by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to prevent 1 million heart attacks and strokes over the next 5 years. millionhearts.hhs.gov/index.html

The Community Transformation Grants program supports community level efforts to reduce chronic diseases such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes. For example, making healthy meals possible in school vending machines. www.cdc.gov/communitytransformation/

Making quality care more affordable by developing and spreading new health care delivery models.

Out of Pocket Expenses

Health Spending per Capita

Percentage of people under 65 years of age with out-of-pocket medical and premium expenses greater than 10% of income

Annual all payer health care spending per person

Not available.

The CMS Innovation Center as a new engine for testing innovative care delivery and payment models that have potential to deliver better health care at lower cost for Medicare, Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) beneficiaries. www.innovations.cms.gov

External drivers of quality

Accreditation

Financial incentives

Performance measurement

Public reporting

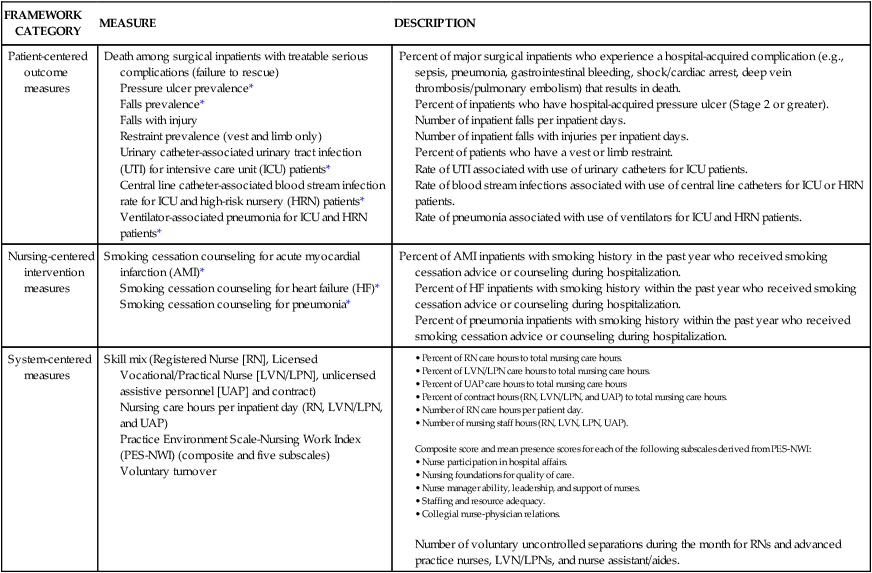

Measuring nursing care quality

FRAMEWORK CATEGORY

MEASURE

DESCRIPTION

Patient-centered outcome measures

Death among surgical inpatients with treatable serious complications (failure to rescue)

Pressure ulcer prevalence*

Falls prevalence*

Falls with injury

Restraint prevalence (vest and limb only)

Urinary catheter-associated urinary tract infection (UTI) for intensive care unit (ICU) patients*

Central line catheter-associated blood stream infection rate for ICU and high-risk nursery (HRN) patients*

Ventilator-associated pneumonia for ICU and HRN patients*

Percent of major surgical inpatients who experience a hospital-acquired complication (e.g., sepsis, pneumonia, gastrointestinal bleeding, shock/cardiac arrest, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism) that results in death.

Percent of inpatients who have hospital-acquired pressure ulcer (Stage 2 or greater).

Number of inpatient falls per inpatient days.

Number of inpatient falls with injuries per inpatient days.

Percent of patients who have a vest or limb restraint.

Rate of UTI associated with use of urinary catheters for ICU patients.

Rate of blood stream infections associated with use of central line catheters for ICU or HRN patients.

Rate of pneumonia associated with use of ventilators for ICU and HRN patients.

Nursing-centered intervention measures

Smoking cessation counseling for acute myocardial infarction (AMI)*

Smoking cessation counseling for heart failure (HF)*

Smoking cessation counseling for pneumonia*

Percent of AMI inpatients with smoking history in the past year who received smoking cessation advice or counseling during hospitalization.

Percent of HF inpatients with smoking history within the past year who received smoking cessation advice or counseling during hospitalization.

Percent of pneumonia inpatients with smoking history within the past year who received smoking cessation advice or counseling during hospitalization.

System-centered measures

Skill mix (Registered Nurse [RN], Licensed Vocational/Practical Nurse [LVN/LPN], unlicensed assistive personnel [UAP] and contract)

Nursing care hours per inpatient day (RN, LVN/LPN, and UAP)

Practice Environment Scale-Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) (composite and five subscales)

Voluntary turnover

Composite score and mean presence scores for each of the following subscales derived from PES-NWI:

Number of voluntary uncontrolled separations during the month for RNs and advanced practice nurses, LVN/LPNs, and nurse assistant/aides.

Benchmarking

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access