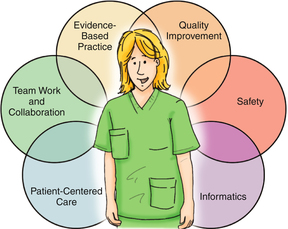

After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Describe driving forces for quality and safety competency in nursing. 2. Define the six core quality competencies integrated into nursing curricula to prepare nurses for working in systems focused on quality. 3. Base nursing care delivery on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes defining the six core competencies. Unintended harm caused by medical care, not by the underlying condition of the patient. A preventable adverse event is one that under the circumstances could have been avoided (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2009a). Benchmark:An attribute or achievement that serves as a standard for other providers or institutions to emulate. Algorithmic listing of actions to be performed for a specific procedure or process designed to ensure that no step will be overlooked. The ability to clearly demonstrate the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and professional judgment required to practice safely and ethically in a designated role and setting. Electronic health record (EHR) A transportable medical record in digital format that serves as the primary source of information for health care, meeting all clinical, legal, and administrative requirements for medical records that can be shared electronically among health care providers and patients. The failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of an incorrect plan to achieve an aim. A “near miss” is when an incident does not cause harm or a potential error is recognized before it happens, thus is prevented. A formal system, either voluntary or mandatory, that collects data pertaining to adverse events for purposes of learning, accountability, or effecting change. Human factors:The study of human abilities and characteristics as they affect the design and smooth operation of equipment, systems, and jobs. An organizational culture that promotes patient safety by acknowledging that competent health care professionals may make mistakes; incidents are analyzed through root cause analysis to determine where system changes can prevent future occurrences. Just culture does not tolerate reckless behavior or a conscious disregard of risk to patients; thus it is not the same as a “no blame” culture (AHRQ, 2009a). Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) A national program with the goal of preparing future nurses with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSA) necessary to continually improve the quality and safety of the health care systems in which they work. SBAR (situation-background-assessment-recommendation) The SBAR technique provides a succinct, structured framework for communication among members of the health care team about a patient’s condition. An unexpected occurrence involving patient death or serious physical or psychological injury unrelated to the natural course of the patient’s care. Serious injury specifically includes loss of limb or function. Such events are called sentinel because they signal the need for immediate investigation and response (The Joint Commission, 2008). Additional resources are available online at: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Cherry/ Vignette After arriving on the unit, Roger reviewed the morning medications for his patient with the assigned RN preceptor who guided him in withdrawing the medications from the automated dispensing cabinet. The RN preceptor verified the medications and assessed Roger’s readiness to administer medications by asking questions about each medication and why it was appropriate for the patient. Roger also confirmed the name and the dose of each medication. Roger’s clinical instructor was available, and so the RN preceptor left to provide care to her other assigned patients. The instructor stopped the intravenous infusion, attempted to aspirate contents, and immediately notified the RN preceptor and nurse manager. The nurse manager quickly contacted the drug information center in the hospital’s pharmacy for advice on management options. The attending physician was also contacted. Within minutes the patient was assessed as stable, and it was determined that no additional treatment could be given to the patient. Questions to Consider While Reading This Chapter: 1. What could Roger, the nursing instructor, or the RN preceptor have done to prevent this error? 3. How can nurses transform their practice by incorporating the six quality and safety competencies as defined by the Institute of Medicine: patient-centered care, teamwork and collaboration, evidence-based practice, continuous quality improvement, safety, and informatics? A mandate for sweeping changes in the U.S. health care system emerged from a series of revealing reports known as the Quality Chasm Series issued by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) detailing significant issues in quality and safety (IOM, 2000, 2001; Greiner and Knebel 2003; Page, 2004). To accomplish its recommendations for a redesigned health system to improve quality outcomes, the IOM declared education as the bridge to quality through major redesign of health professions education focusing on six core competencies: These six competencies should form the practice base for all health professionals (Greiner and Knebel 2003). This chapter examines how nurses’ work is being redesigned in response to the IOM challenges with discussion of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required as new roles and responsibilities emerge. The United States is considered to have the world’s most technologically advanced health care system delivered by a dedicated and highly skilled workforce, state-of-the-art technology, and advanced pharmacologic agents. It is also recognized as the most expensive system in the world (Davis et al, 2007; Schoen et al, 2011). Still, failures in the system occur with some regularity. Health care lags behind other high-performance industries such as aviation and nuclear power in focusing on quality and safety as the industry standard (IOM, 2000). Through the Quality Chasm reports, the IOM has sustained the emphasis on the imperative to transform the U.S. health care system in order to address inconsistent outcomes and prevent errors (IOM, 2001, 2000). Poor quality outcomes and medical errors erode public confidence, increase health care costs, and increase morbidity and mortality. Simply put, health care errors strike at the heart of the health care system—the responsibility to do good and avoid harm (Cronenwett et al, 2007). Progress, however, has been slow, and efforts to transform systems continue (Wachter, 2010). Recommendations for health professions’ education outlined in the 2003 Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality (Greiner and Knebel, 2003) identify competencies or abilities that all health care professionals should achieve to transform health care systems, reduce errors, and improve quality outcomes. Educators are mindfully altering educational experiences to help students form a professional identity in preparation to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interprofessional team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement, and informatics (Cronenwett et al, 2007; Greiner and Knebel, 2003). The competencies are not discrete concepts but overlap; it is difficult to work on any one without an overlay of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that define another. Underlying concepts for redesigned systems recognize that health care organizations, like other high-reliability industries, are complex, internally dynamic, and interactive. They are charged with performing exacting tasks under considerable time pressures and sometimes, extreme conditions, yet work with a focus on where the next adverse event will occur as a major prevention strategy. Such organizations recognize that changing the system requires understanding the circumstances at every step of an event by studying what happened; these are referred to as organizations with a safety culture (Sammer et al, 2010). What is learned is applied to prevent future occurrences. Shifting from an individual blame approach to a system approach allows the integration of all the competencies that include the patient and family as partners in creating a safer system. As systems redesign around quality and safety, nurses have opportunities for helping shape health care and improve outcomes. Emerging opportunities for nurses to have key roles in transforming the health care system require new learning experiences and incorporating the six competencies from the IOM’s recommendations. Through support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the national Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (www.QSEN.org) project was created to develop and facilitate the execution of changes in nursing education (Cronenwett et al, 2007), to offer new opportunities for faculty development, and to learn from a 15-school pilot collaborative (Cronenwett et al, 2009). Leading scholars in each of the six competencies as well as pedagogical experts were selected as QSEN faculty to lead the change. Recognizing that policy changes would be needed to achieve curricula innovation, a QSEN advisory board included leaders from regulatory agencies who define educational standards, physicians to cross-walk with changes in medical education, and innovators with experience in leading other major educational changes (Cronenwett et al, 2007). The groups used an iterative process beginning with a literature review, a draft of definitions including the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of the IOM competencies relevant to all entry-level registered nurses (RNs), and discussion of pedagogies for achieving behavioral changes. Although the IOM identified five competencies, the QSEN faculty determined that quality and safety should be separate competencies because of the science supporting each of these areas. The six competencies, at first look, appear to be familiar topics to faculty and students, as indicated in a 2007 survey of schools to determine if they are teaching this content (Smith et al, 2007), yet focus groups indicated the need for faculty development and translation into curricular essentials. The six competencies were incorporated into nursing education standards and the licensure examination (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2008; Smith et al, 2007) so that all nurses will be held accountable. The QSEN website (www.QSEN.org) posts information on the competencies, an annotated bibliography for each competency, peer-reviewed teaching strategies, instructional videos, and other resources. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation supported the Pilot School Collaborative to model how faculty could include the six competencies in prelicensure programs. Fifteen schools, representing BSN, ADN, and diploma programs, completed curricular mapping and exemplar projects, posted on the QSEN website (Cronenwett et al, 2009). Schools completed a student survey of graduating seniors to determine student self-assessment of their mastery of the competencies (Sullivan et al, 2009). Findings reinforced the value that recent graduates and faculty place on the competencies, the need to increase knowledge about patient safety practices, and the opportunities for faculty development and redesigned student learning experiences. The essential feature of patient-centered care is knowing the patient well enough to be able to see health care situations through the patient lens (Cronenwett et al, 2007; Walton and Barnsteiner, 2012) with recognition of the patient’s values and health beliefs. It involves eliciting and incorporating patient preferences and values into the plan of care. In a patient-centered care model, patients and families participate in nursing and medical decision making and in care coordination with all members of the health care team (Chapman, 2009). Patient-centered care respects the diversity of the human experience so that nurses must examine their own attitudes about working with individuals and groups whose values differ from their own. Examples of critical questions to ask in a patient-centered care approach include the following: • “What is the most important thing I could do for my patient at this moment?” (Day and Smith, 2007) • How can the patient and/or family participate in accurately assessing the patient’s pain and determining the best pain management plan that recognizes the individual patient’s attitudes and expectations about pain and suffering? • How can I assist family members with visiting hours and access to their family member to allay anxiety and include them as partners in care?

Quality and Safety in Nursing Education

The QSEN Project

Chapter Overview

Quality and Safety: the New Standard for Nursing Education

History of Quality and Safety Education in Nursing Project

Patient-Centered Care

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Quality and Safety in Nursing Education: The QSEN Project

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access