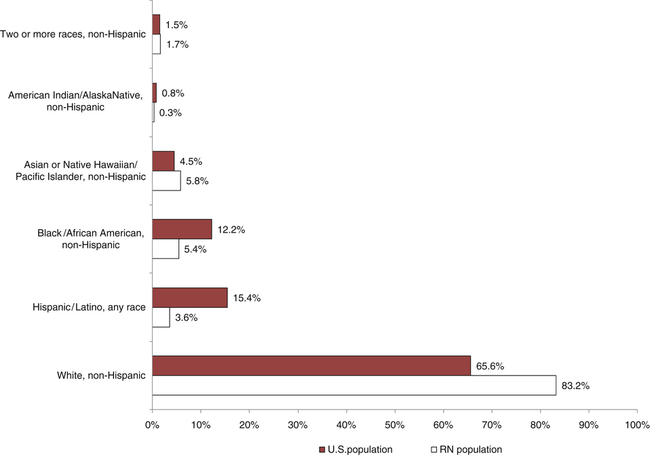

After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Integrate knowledge of demographic and sociocultural variations into culturally competent professional nursing care. 2. Provide culturally competent care to diverse client groups that incorporates variations in biologic characteristics, social organization, environmental control, communication, and other phenomena. 3. Critique education, practice, and research issues that influence culturally competent care. 4. Integrate respect for differences in beliefs and values of others as a critical component of nursing practice. The process of becoming adapted to a new or different culture. The cultural absorption of a minority group into the main cultural body. Combining two distinct cultures in a single region. Incorporates a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, to redressing the power imbalances in the patient-clinician dynamic and to developing mutually beneficial and advocacy partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations (Tervalon and Murray-Garcia, 1998). Experienced when neutral language, both verbal and nonverbal, is used in a way that reflects sensitivity and appreciation for the diversity of another (American Academy of Nursing Expert Panel on Cultural Competence, 2007). Shared values, beliefs, and practices of a particular group of people that are transmitted from one generation to the next and are identified as patterns that guide thinking and action. Adaptation to the prevailing cultural patterns in society. Affiliation resulting from a shared linguistic, racial, or cultural background. Believing that one’s own ethnic group, culture, or nation is best. A subgroup of the population that tends to be hidden, overlooked, or on the outer edge. An ethnic group smaller than the majority group. Preconceived, deeply held, usually negative, judgment formed about other groups. Assigning certain beliefs and behaviors to groups without recognizing individuality. Being grounded in one’s own culture, but having the skills to be able to work in a multicultural environment. Perspective shared by a cultural group of general views of relationships within the universe. These broad views influence health and illness beliefs. Additional resources are available online at: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Cherry/ VIGNETTE Questions to Consider While Reading This Chapter 1. What preconceived ideas do you have about the following cultural groups: Hispanic, Appalachian, Moroccan, African-American, South African, and Chinese? 2. What strategies can you implement to overcome prejudice? 3. How can nurses provide effective care to different cultural groups who each have a unique set of beliefs about illness? The United States has always been represented by a culturally diverse society. However, the volume of cultural groups entering our country is increasing rapidly. Professional nurses must provide care to persons of various cultures who have different values, beliefs, and perceptions of health and illness. This chapter explores cultural phenomena, including environmental control, biologic variations, social organization, communication, space, and time in relation to major cultural groups. It also examines different views toward health, illness, and cure. Federally defined minority groups, which include African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and American Indians, are emphasized, although the needs of marginalized populations, such as the homeless, refugees, and older adults also are addressed. The need for diversity in the health care force is explored, and strategies for recruiting and retaining minorities in health care are suggested. Strategies that nurses can use to increase their own cultural competence also are given. The demographic and ethnic composition of the U.S. population has experienced a marked change in the past 100 years. The United States always has been a multicultural society, although changes in immigration laws have increased the number of cultural groups entering the United States (Nies and McEwen, 2011). Minority groups have grown faster than the population as a whole. If migration trends continue, by the mid–twenty-first century minority populations will outnumber the white population. Approximately 1 in every 3 Americans will be an ethnic minority. In some U.S. cities, the number of persons from diverse cultural groups is increasing at such a rapid pace that minorities constitute more than half the population. The nation will be more racially and ethnically diverse, as well as much older, by midcentury, according to 2009 projections released by the U.S. Census Bureau. The older population is experiencing significant growth. More people were 65 years of age and older in 2010 than in any previous census. Between 2000 and 2010, the population 65 years of age and older increased at a faster rate (15.1%) than the total population (9.7%). The aging population includes an increasing number of adults older than 85 years of age (Census Brief, 2010). This demographic change introduces many interrelated social, economic, political, educational, and health problems. The fact that people are living longer allows more opportunity for the development of chronic illness. Social isolation and depression that result from losses of friends and family will present a challenge for mental health care providers. Primary care providers will be faced with identifying risks to independence and health for the aging population (Eliopoulos, 2010). Federally defined minority groups are African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, and Asians or Pacific Islanders. The populations within the federally defined minority groups have grown faster than the population as a whole. In 1970, minority groups accounted for 16% of the population. If current trends continue, the U.S. Census Bureau (2010) predicts that by 2025 minorities will account for more than 55% of the population, thus making up a majority of the total population for the first time (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010; National Institutes of Health National Heart Lung and Blood Institute). (Visit www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/factbook/chapter4.htm for more information.) Although tremendous strides have been made in improving health and longevity in the United States, statistical trends show a disparity in key health indicators among certain subgroups of the population. There is a racial gap between African Americans and whites of 5.6 years, with average life expectancy of 78 years for whites and 72.7 years for African Americans. The infant death rate for African Americans is twice that of whites (Nies and McEwen, 2011). Although the ranking of health problems according to excess deaths differs for minority groups, the six causes of death that are a priority are cancer, heart disease and stroke, chemical dependency, diabetes, homicide and accidents, and infant mortality (Nies and McEwen, 2011). Not only should the concern for culturally competent care focus on ethnic minorities and populations with a different heritage than Euro-Americans, but it should consider the needs of marginalized populations (Hall et al, 1994), which live on the periphery or in between. Examples of such populations include gays and lesbians, older adults, recently arrived immigrants (e.g., from Russia, Afghanistan, and Rwanda), and groups that have been in this country for some time (e.g., from South America and the Middle East) who are less visible than the federally defined minorities (Lenburg et al, 1995). Their lives and health care needs often are kept secret and are understood only by them. Marginalized populations usually have extreme insights about their health care needs, although they often seem voiceless. This is in part a result of the different ways in which they both communicate and are silenced. It also may be because they feel even more peripheral or shut out from mainstream society when they are ill or experiencing a crisis. Changing world economics have had profound consequences, such as increased joblessness, homelessness, poverty, and limited access to health insurance and health care. Anxiety, hopelessness, depression, and despair commonly affect the individuals in our society who find themselves suddenly without a job and sometimes even without a home as a result of downsizing. These conditions often are associated with increased stress-related symptoms, substance abuse, violence, and crime (Lenburg et al, 1995). Dramatic changes in technology and specialization in the health care field have made health care costs skyrocket. Therefore, not everyone can afford health care services. More minorities lack health insurance than the general population (Nies and McEwen, 2011). Higher costs and lower wages for minority groups make it difficult to rise out of poverty (Stanhope and Lancaster, 2010). Most families with racially or ethnically diverse backgrounds have a lower socioeconomic status than does the population at large. African Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians have much higher rates of poverty than non-Hispanic whites and Asians. The median family income of Asians is slightly higher than that of non-Hispanic whites and is consistent with Asians’ high levels of education and the higher percentage of families with two wage earners. However, opportunities for education, occupation, income earning, and property ownership that are available to upper- and middle-class Americans often are not available to members of minority groups (Stanhope and Lancaster, 2010). The poor also suffer more than the population as a whole for nearly every measure of health. Substantial disparities remain in health insurance coverage for certain populations. Among the nonelderly population, approximately 30.7% of Hispanic persons have the highest uninsured rates of any racial or ethnic group within the United States. For African Americans, the percentage of uninsured in 2010 was 20.8%. Lack of health care coverage has major implications for health (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Visit www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/2011/data/incpovhlth/2010/highlights.html for more information. Minority members of society often live in poverty. This social stratification leads to social inequality. For instance, it is widely known that school systems and recreational facilities vary significantly between the inner city and the suburbs (Nies and McEwen, 2011). Residential segregation, substandard housing, unemployment, poor physical and mental health, and poor self-image are part of the cycle of poverty. This inequality is especially disturbing as it relates to health care. The United States has a history of providing the highest quality health care to those with the highest socioeconomic status and the worst health care to those with low socioeconomic status. Social, economic, and health problems have led to heated debates about the philosophy, scope and costs, and sources of funding for health care and insurance programs. Changing economic and social conditions have contributed to the increasing level of violence in our society. Statistics indicate that homicide is the second leading cause of death among Americans 15 to 24 years of age and the leading cause of death among African-American males 15 to 34 years of age (Nies and McEwen, 2011). Businesses, schools, restaurants, playgrounds, and churches have become common settings for random acts of violence (Lenburg et al, 1995). Unemployment is associated with violence because it is an expectation in our society that people should be productive and gainfully employed. The inability to secure or hold a job may lead to feelings of inadequacy, guilt, and frustration, which in turn can precipitate acts of violence. Although the increasing incidence of violence affects all segments of society, women, children, older adults, and culturally vulnerable groups are especially at risk. Unemployment rates among young minority men in the United States are consistently high (Stanhope and Lancaster, 2010). This group also has the highest rate of violence, with homicide being a major problem for young African-American males. The differing rates of violence among races are more likely a result of poverty than race (Stanhope and Lancaster, 2010). Intimate partner violence (IPV), formerly known as domestic violence, is the single greatest cause of injury to women 15 to 24 years of age. IPV crosses all ethnic, racial, socioeconomic, and educational lines. It includes battering, resulting in physical injury, psychological abuse, and sexual assault (Nies and McEwen, 2011). Societal changes have increased the tension between the empowered culturally dominant groups and the less visible vulnerable groups. This tension and behavioral response to tension has major implications for health care delivery and the education of nurses and other health care professionals (Lenburg et al, 1995). Members of some cultural groups are demanding culturally relevant health care that incorporates their beliefs and practices (Nies and McEwen, 2011). Consumers are becoming much more aware of what constitutes culturally sensitive and competent care and are less willing to accept incompetent care (Meleis et al, 1995). There is a lack of diversity and ethnic representation of health care professionals, and there is limited knowledge about values, beliefs, experiences, and health care needs of certain populations, such as immigrants, older adults, and gays and lesbians. Each of these groups has a unique set of responses to health and illness. Nurses make up the largest segment of the workforce in health care delivery. Therefore they have an opportunity to be proactive in changing health care inequities and access to health care (Meleis et al, 1995). The changing health care system must reflect the community, and, as health care moves into the community, it is vital that partnerships be formed between health care providers and the community. For these partnerships to become a reality, minority representation in all health professions is vital. Factors inhibiting minority members from attaining a career in nursing include inadequate academic preparation, especially in the sciences; financial costs; inadequate career counseling; and better recruitment efforts by other disciplines (Sullivan, 2004). Although most nurses are white women, an increasing proportion of minority students is graduating from nursing programs. In a survey conducted by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) in 2011, minority representation in baccalaureate programs was highest among those identified as black or African American (10.3%) and lowest among American Indian/Alaska Natives (0.5%). Graduates from Hispanic or Latino groups totaled 7% and Asians 7.8%. Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islanders were 1% of the undergraduate students who responded to the survey. These totals lag behind the 72% reported white enrollment (Fang, Li, and Bednash, 2012). The number of men who graduate from basic registered nurse (RN) programs is also increasing. In the AACN survey conducted in 2011, 11.5% of the undergraduate respondents were men. Men continue to represent a minority in nursing, although recruitment efforts have focused more on men and minorities. Ad campaigns have highlighted men who were formerly firefighters, emergency responders, and law enforcement officers who have made the decision to pursue nursing as a career (Fang, Li, and Bednash, 2012). The racial and ethnic distribution of the RN population is substantially different from that of the U.S. population as a whole. Of the nurses who indicated their racial or ethnic background in 2008, 83.2% were white, non-Hispanic as compared with 65.6% of the U.S. population; 5.4% were black or African-American, non-Hispanic; 5.8% were Asian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic; 3.6% were Hispanic; and 0.3% were American Indian or Alaska Native (Health Resources Service Administration [HRSA], 2010) (Figure 10-2). These figures are staggering in light of the demographics of our society. Although the number of minority nurses is increasing, the numbers have failed to keep up with our increasingly diverse population. Men constituted 6.6% of the RN population in 2008, a small increase from 5.8% in 2004. Only 4.1% of nurses who graduated in 1990 or earlier were male, while 9.6% of those who completed their initial RN education after 1990 were male. The initial nursing preparation for more male RNs was an associate’s degree. The percentages of male and female RNs completing a baccalaureate or higher degree initial nursing program were similar, 32.7% and 31.5%, respectively (HRSA, 2010). It is clear that we have been slow in preparing nurses to be reflective of our population, just as we have been unaware of the need for culturally sensitive patient care and sometimes less than welcoming to students different from the preponderant population (Sullivan, 1998). Recruitment and retention of students from minority populations must not be separated. In other words, recruitment programs must have retention as their primary focus because there is no point in recruiting minorities into nursing programs and then not helping them succeed. In 1997, the American Nurses Foundation published a report of a project it had funded titled Strategies for Recruitment, Retention and Graduation of Minority Nurses in Colleges of Nursing. Through survey and interview analysis, Bessent and a cadre of knowledgeable leaders investigated the most effective approach to increase the nursing profession’s representation of minority nurses (Bessent, 1997). Members of Chi Eta Phi, a national African-American nursing society with chapters throughout the country, serve as mentors to minority nursing students. As mentors, sorority members provide intellectual and inspirational stimulation along with counseling. All national nursing organizations, the federal Division of Nursing, hospital associations, nursing philanthropies, and other stakeholders within the health care community agree that recruitment of underrepresented groups into nursing is a priority for the nursing profession in the United States (AACN, 2010). For more information, visit http://www.aacn.nche.edu/media-relations/fact-sheets/enhancing-diversity. Nursing shortage reports, including those produced by the American Hospital Association, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), the Joint Commission, and the Association of Academic Health Centers, point to minority student recruitment as a necessary step to addressing the nursing shortage. For more information on these reports, visit http://www.aacn.nche.edu/media-relations/fact-sheets/nursing-shortage. Another successful strategy for recruiting and retaining minorities in education and clinical practice is matched mentoring, which involves matching same-culture mentors either in the same institution or different institutions. A different mentoring strategy involves teaching and modeling by nurses who have been trained in cross-cultural care. Cross-cultural nursing consultants in the care of specific groups are available to agencies, professional groups, licensing bodies, and individual nurses. (Organizations should contact the Transcultural Nursing Society at www.tcns.org to obtain the names of consultants in the field of transcultural nursing.) Health professionals, educators, and health care systems must all respond to the consequences of increasing cultural diversity for the future well-being of all populations. There is a shared responsibility to work collaboratively to achieve competence in nursing practice in order to deliver patient-centered care. It is evident that professional competence must incorporate cultural competence and the skillful use of knowledge and interpersonal and technical abilities (Lenburg et al, 1995). Evaluation of cultural competence in students, faculty, and staff is essential. The authors suggest that it is essential that nurses take responsibility to: • Be sensitive to and show respect for the differences in beliefs and values of others. • Take responsibility to inquire, learn about, and integrate beliefs and values of others in professional encounters. • Take responsibility to try to change negative and prejudicial behaviors in themselves and others. • The nurse’s culture often is different from the client’s culture. • Care that is not culturally competent may be more costly. • Care that is not culturally competent may be ineffective. • Specific objectives for persons in different cultures need to be met as outlined in Healthy People 2020. • Racial and minority groups experience profound disparities in health and health care. • Nursing is committed to social justice, providing safe quality care to all. • Nurses are expected to respond to global infectious disease epidemics. • Achieving cultural competence should be our goal, although it may take most of us a lifetime to attain. However, we can all aspire to achieve cultural humility, which incorporates a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, to redressing the power imbalances in the patient-clinician dynamic, and to developing mutually beneficial and advocacy partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations (Tervalon and Murray-Garcia, 1998). If we acquire cultural humility we should also demonstrate cultural sensitivity that shows appreciation of the diversity of others.

Cultural Competency and Social Issues in Nursing and Health Care

Chapter Overview

Population Trends

Federally Defined Minority Groups

Marginalized Populations

Economic and Social Changes

Poverty

Violence

Diversity in the Health Care Workforce

Need for Diversity in the Health Care Workforce

Current Status of Diversity in the Health Care Workforce

Recruitment and Retention of Minorities in Nursing

Strategies for Recruitment and Retention of Minorities in the Health Care Workforce

Cultural Competence

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access