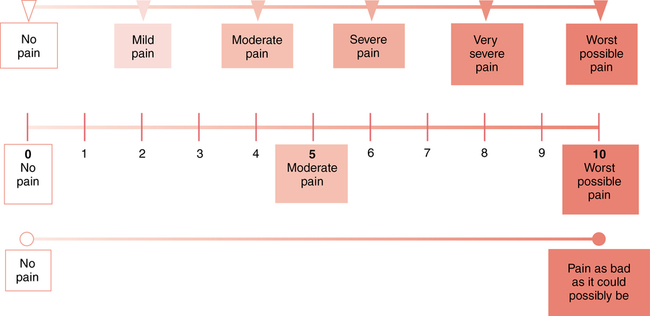

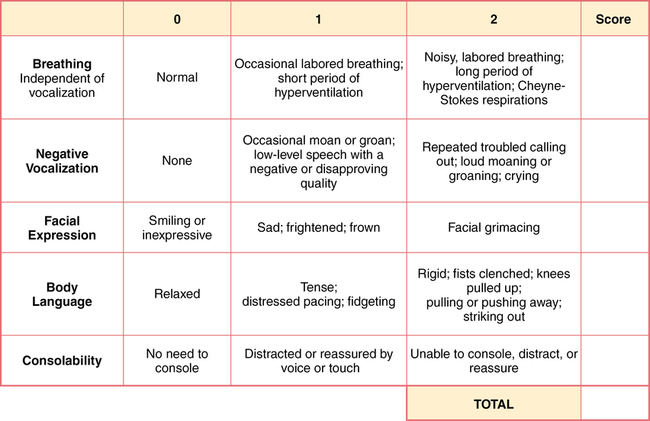

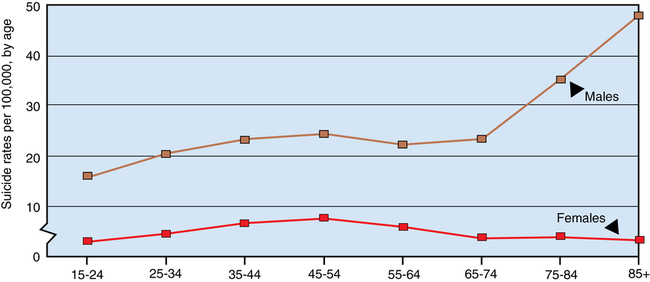

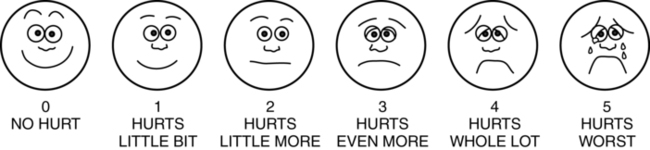

CHAPTER 30 1. Describe mental health disorders that may occur in older adults. 2. Discuss the importance of pain assessment, and identify three tools used to assess pain in older adults. 3. Explain the importance of a comprehensive geriatric assessment. 4. Recognize the significance of health care costs for older adults. 5. Discuss facts and myths about aging. 6. Analyze how ageism may affect attitudes and willingness to care for older adults. 7. Identify the requirements for the use of physical and chemical restraints. 8. Identify legislation and legal documents that protect the rights of older patients, and describe their impact on nursing care. 9. Describe the role of the nurse in various geriatric care settings. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Touhy (2012) provides a common classification for people 65 and older: Depression accounts for up to 70% of late-life suicides. The risk of suicide for men increases with age, particularly for white men ages 65 and older whose risk is 7 times that of females of the same age. The highest rate of suicide is in males 75 and older at 36 per 100,000; the rate of suicide for males and females aged 75 and older is about 16 per 100,000 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). Even though the suicide rate among older adults is high, especially among white, non-Hispanic males (Figure 30-1), suicide in this group is probably underreported. The numbers also do not reflect those who passively or indirectly commit suicide by abusing alcohol, starving themselves, overdosing or mixing medications, stopping life-sustaining drugs, driving into bridge abutments, or simply losing the will to live. There is an ongoing effort to educate primary care providers to better recognize, treat, and refer older adults to mental health care providers. There is clear evidence that treating depression is cost effective and decreases health care expenditures (NIMH, 2004). Chapter 25 provides an in-depth discussion of suicide. Early identification and treatment for depression are key measures for suicide prevention. Risks for suicide include demographics, diagnosable psychiatric illness (psychosis, anxiety, substance abuse, previous suicide attempts), psychological well-being (personality, emotional reactivity, impulsiveness), biological status (dysfunction of neurotransmitters), and stressful life events (Nock et al., 2008). Other risk factors include access to weapons, access to large doses of medications, and chronic or terminal illness. Protective factors include religious beliefs and practices, spirituality, perception of social/family support, and having children. Specific anxiety disorders peak at various ages (Lenze & Wetherell, 2011). This may be related to changes in brain structure or function. In older adults, anxiety disorders are even harder to diagnose, and prevalence estimates vary greatly. One unique anxiety in the elderly is the fear of falling; its impact on keeping the elderly at home is similar to agoraphobia. Psychosocial risk factors for anxiety include being childless, low socioeconomic status, and having experienced trauma. Protective factors may include social support, spiritual beliefs, physical activity, cognitive stimulation, and having acquired effective coping strategies. Cassidy and Rector (2008) identify anxiety disorders in late life as “The Silent Geriatric Giant.” Older adults often have multiple physical complaints, medication problems, pain, sleep disturbances, and psychiatric illness. Anxiety is twice as prevalent as dementia and four to eight times as common as major depressive disorders. Treatment for anxiety disorders typically includes an SSRI along with cognitive behavioral therapy. Roy-Byrne and colleagues (2010) showed that relaxation training was an effective intervention for older adults. Antianxiety (benzodiazepines) agents are also used and frequently overprescribed. They should be used cautiously, as side effects can result in confusion, oversedation, increased risk of falls, and paradoxical agitation. Anxiety disorders are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 15. Delirium is a medical condition caused by physiological changes due to underlying pathology. It causes fluctuations in consciousness and changes in cognition that develop over a short period of time (hours to days). There is usually evidence from history, examination, or diagnostic testing that will help identify the cause (Caplan et al., 2010). Patients may be disoriented and often assumed to be demented because of their age; therefore, it is crucial to obtain data from family or caregivers about a baseline level of functioning. A patient who is newly confused, falling, disrobing, and fighting with staff should be assessed for delirium. Asking questions such as “Has your mother been shopping and cooking for herself?” or “Does she pay her own bills?” or “Does she ever get lost when driving?” may give subtle clues about whether changes are acute or have been coming on slowly. Other questions that can be revealing include “Has your father been started on any new medication?” or “Has your father fallen or hit his head recently?” Dementia is usually of the Alzheimer’s or vascular type. Both are characterized by aphasia (difficulty finding words), apraxia (difficulty carrying out motor functions despite intact functioning), agnosia (failure to recognize objects), and disturbances in executive functioning (organizing, planning, abstracting, insight, judgment) (Falk & Wiechers, 2010). Changes in executive functioning may include forgetting how to make old family recipes, the inability to manage bill paying, and limited insight and judgment, leading to increased vulnerability to exploitation. Another symptom that often is not discussed is sexual disinhibition. Older patients may be overly flirtatious, grope caregivers or family during care, make sexually inappropriate comments, expose genitalia, or masturbate openly. These types of behaviors can cause staff and family to be uncomfortable and confused about how to respond. It is important for the nurse to be open and understanding about such behaviors and to recognize them as symptoms of a frontal lobe brain dysfunction. Chapter 23 presents a more complete description of delirium and dementia. The risk factors for heavy drinking in older adults are being male and single, having less than a high school education, low income, and smoking (Karlamangla et al., 2006). Additionally, depression often plays a role in increased alcohol consumption in the elderly (National Institute on Aging, 2012). Identifying alcohol and substance abuse is often difficult because the accompanying personality and behavioral changes associated with alcohol abuse frequently go unrecognized in older adults. Caution is required when medicating the older adult who abuses alcohol. Central nervous system toxicity from psychoactive drugs increases with aging. Ingestion of antidepressants or tranquilizers can be particularly harmful because their effect is further potentiated by alcohol. Whenever there is a suspicion or indication that an older adult is abusing alcohol, the health care provider should conduct a screening test. The MAST-G (Box 30-1) is an instrument commonly used to assess older adults’ alcohol use. Moos and colleagues (2010) conducted a study where participants were followed over a 20-year span. Drinking excessively late in life was found in about 33% of participants. Indicators of excessive use were past drinking history, reliance on substances for stress reduction, and support of peers in drinking behavior. There is evidence that older adults respond to treatment as well as, if not better than, younger adults. Intentional brief intervention by a health care provider or participation in a group setting can impact older adults to decrease alcohol consumption. Group therapy along with self-help groups like Alcoholics Anonymous can be effective. It is important that health care providers recognize this recovery potential. Pain is common among older adults and affects their sense of well-being and quality of life. Up to 85% of the older population is thought to have conditions that predispose them to pain. These conditions include arthritis, peripheral vascular disease, and diabetic neuropathy. Pain is also associated with depression. Jann and Slade (2007) describe three categories of depressive symptoms: emotional (mood, motivation, apathy, anxiety), cognitive (concentration, memory), and physical (insomnia, fatigue, headache, and stomach, back, and neck pain). McDonald and colleagues (2009) demonstrated that the phrasing of pain-related questions with older adults influenced their report. The use of open-ended questions such as “Tell me about your pain, aches, soreness, or discomfort” yielded significantly more information than use of a pain scale alone. When pain is suspected, the nurse begins with a physical assessment for medical origins of the pain and assesses the level of pain. The Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (Hockenberry & Wilson, 2012) (Figure 30-2) is an active assessment instrument. The FACES scale shows facial expressions on a scale from 0 (a smile) to 5 (crying grimace). Respondents are asked to choose the face that depicts the pain they feel. The present pain intensity (PPI) rating from the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) (Davis & Srivastana, 2003) is another tool accepted for use with older patients. Patients are asked to respond by selecting the description (from “no pain” [0] to “excruciating pain” [5]) that they believe identifies the pain they feel. The Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale is used to evaluate the presence and severity of pain in patients with advanced dementia who no longer have the ability to communicate verbally (Figure 30-3). The scale evaluates five domains: breathing, negative vocalization, facial expression, body language, and consolability (Box 30-2). The score guides the caregiver in the appropriate pain intervention. The treatment of acute pain is different from the approach for chronic pain. Acute pain can be helped with analgesics, such as opioids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), COX-2 inhibitors, and non-narcotic agents, such as tramadol. Chronic pain is treated with pain modulators such as gabapentin, pregablin, SNRIs, and TCAs. Consultation with a pain-management specialist is often helpful with chronic pain syndromes. Some considerations in pharmacological pain management in older adults are listed in Box 30-3. The current trend is to not utilize opioids for non–cancer-related chronic pain due to strong evidence that the risks are significant, including increased risk of fractures, hospitalization, and mortality. Prescribers also reported concern about abuse of opioids by family and friends.

Psychosocial needs of the older adult

Mental health issues related to aging

Late-life mental illness

Depression

Depression and suicide risk

Anxiety disorders

Delirium

Dementia

Alcohol abuse

Pain

Barriers to accurate pain assessment

Assessment tools

Pain management

Pharmacological pain treatments.

Psychosocial needs of the older adult

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access