Chapter 8 Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

This chapter begins with an overview of the underlying assumptions of psychodynamic psychotherapy, the history, and evidence-based research. Psychodynamic psychotherapy is discussed as on a continuum, with supportive, expressive, and psychoanalytic approaches considered. Rationale is provided for choice of approach based on developmental considerations for clinical decision-making. The working-through phase of treatment is examined, as is working with alliance ruptures and dreams. Guidelines for brief psychodynamic psychotherapy are provided with case studies illustrating concepts and techniques throughout the chapter. Those skilled in psychodynamic psychotherapy recognize the difficulties in suggesting specific standardized techniques, because technique is driven by the context of the interaction.

The context of managed care, in which a course of psychotherapy is often three to six sessions, makes practicing any meaningful relationship-based work difficult, if not impossible. With these limitations in mind, an overview of relevant concepts and technical considerations is presented. The chapter ends with information about post–master’s training and certification requirements for psychodynamic psychotherapy. Chapters 3 and 5 review the basic concepts of transference, countertransference, and resistance, which are foundational to understanding psychodynamic psychotherapy.

With the American Psychiatric Association’s 2002 mandate that all psychiatric residency training programs teach long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy to meet standards of accreditation, the relevance and importance of this type of therapy has been affirmed by the psychiatric establishment (Gabbard, 2004). Knowledge about psychodynamic psychotherapy is essential for all advanced practice psychiatric nurses (APPNs) to deepen understanding about development and how the patient’s history is re-enacted in the nurse-patient relationship in therapy and in life. Even if the APPN is using another approach, it is still important to understand the person’s dynamics to inform decisions about treatment. The patient does not necessarily need to achieve dynamic insights to experience symptom reduction and personal growth, but developmental considerations, anxiety, transference, countertransference, implicit memory (unconscious), defenses, motivation, and resistance are relevant in any therapeutic encounter. Knowledge about psychodynamic theory is also important for APPNs to communicate with other mental health disciplines. The literature in nursing reiterates the importance of psychodynamic theory for understanding the psychodynamics in the nurse-patient relationship and the inner world of both the nurse and the patient (Gallop & O’Brien, 2003). These authors stress that without knowledge of psychodynamic psychotherapy, nurses are at a tremendous disadvantage and at risk for acting inappropriately and not in the patient’s best interests.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy requires intensive teaching and experience to attain competency. This chapter lays the foundation for the APPN who wishes to understand the basics of this approach. Competencies in psychodynamic psychotherapy include using developmental models to understand personality and psychopathology, formulating a psychodynamic explanation and plan treatment, tracking the issue that is the focus of treatment, implementing the process of therapy, and managing the relationship (Binder, 2004).

Underlying Assumptions of Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

Psychodynamic psychotherapy is derived from psychoanalytic psychotherapy, which was developed by Sigmund Freud at the end of the 19th century. This type of therapy is also referred to as insight-oriented, intensive, exploratory, expressive, and depth psychotherapy. Underpinnings of psychodynamics are rooted in developmental theory, with the basic premise that what has happened in the past determines what we are doing today. It is thought that through understanding these factors, the person become empowered and is then free to make more conscious decisions and consequently live a more satisfying and useful life.

Blagys & Hilsenroth (2000), in an extensive review of the literature, discussed factors that distinguish psychodynamic from cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). These include emphasis on the past; focus on expression of emotion; identification of patterns in actions, thoughts, feelings, experiences, and relationships; emphasis on past relationships; exploration of and working with resistances that impede treatment; exploration of intrapsychic issues through asking about wishes, dreams, and fantasies; and emphasis on the transference and the working alliance. Gabbard (2004) identifies seven key concepts of psychodynamic psychotherapy: unconscious mental functioning, a developmental perspective, transference, countertransference, resistance, psychic determinism, and unique subjectivity. Gabbard explains unique subjectivity as the therapist’s challenge to pursue the patient’s subjective truth and true self, which most likely has been thwarted by parents who cannot recognize, validate, and appreciate this self.

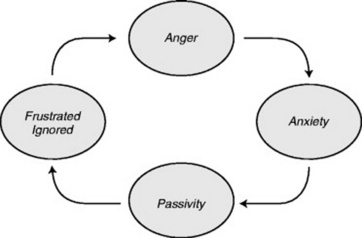

All psychodynamic schools emphasize the centrality of conflict among powerful desires, wishes, and fears. Psychodynamic clinicians believe that to help the person, it is essential to understand how these conflicts are enacted in the present. Psychodynamic theorists agree that understanding unconscious psychological structures and patterns in daily life, as well as how they interact and maintain each other, is essential to understanding the person (Safran & Muran; 2000; Wachtel, 1993). Wachtel (1993) points out that a key characteristic of this pattern is irony; the person ends up in the very position that he was trying hard to avoid. For example, the person who is fearful of feelings of anger may act overly nice, unassertive, and maintain a passive stance toward others. This allows others to ignore his needs, and consequently, he begins to feel frustrated and devalued, which leads to more anger and more anxiety, and the pattern is repeated. Another example is a person who fears hostility from others and interprets every interaction as potentially hostile, preemptively acting in self-protective hostility toward others, which evokes hostility from others, which leads to more anxiety, and so on (Figure 8-1).

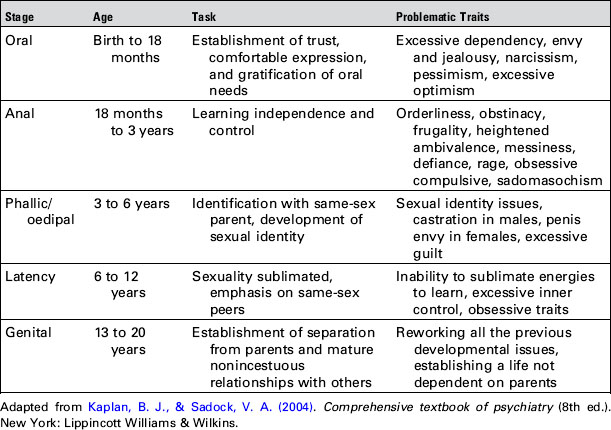

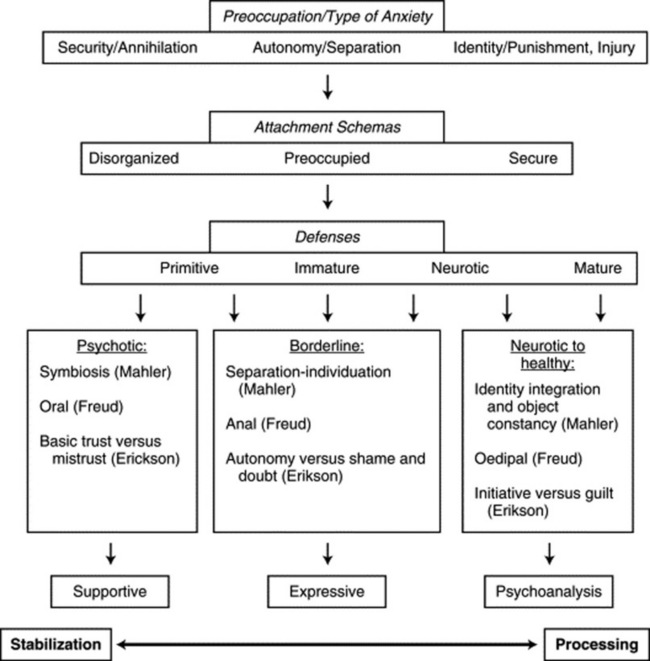

Anxiety is central to understanding these difficulties, and even if the person does not feel particularly anxious, defenses and characterlogical personality traits embedded in implicit memory systems bind the person to a life that is restrictive as compromises are made to keep anxiety at bay. Specific anxieties arise at every level of development, with various theorists positing different tasks based on various theoretical models (Tables 8-1 through 8-3). For each developmental stage, anxiety revolving around a specific issue is negotiated, and if successful, the fear surrounding that phase is assuaged so the person is then able to proceed to the next stage without being preoccupied by that threat (McWilliams, 1994). For example, in early infancy, a major preoccupation is security, with annihilation the threat if the attachment to the mother is threatened or not present; for early childhood, the issue is autonomy, with the concomitant anxiety revolving around separation (i.e., how to be an independent agent and still maintain a relationship with the caregiver); for later childhood, issues of identity must be resolved, with fears of punishment, injury, and loss of control important to resolve. To regulate the anxiety associated with each stage and other painful affects, defense mechanisms develop in implicit memory networks through interaction with caregivers and interpersonal experiences.

Table 8-2 Mahler’s Stages of Separation-Individuation

| Phase | Age | Task |

|---|---|---|

| Normal autism | Birth to 1 mo | Fulfillment of basic need for survival and comfort |

| Symbiosis | 1–5 mo | Awareness of external source for need fulfillment |

| Separation-individuation: | ||

| Differentiation | 5–10 mo | Recognizes separateness from caretaker |

| Practicing | 10–16 mo | Increased independence and separateness of self |

| Rapprochement | 16–24 mo | Seeks emotional refueling from caretaker to maintain feeling of security; borderline pathology thought to evolve from problems in this phase |

| Consolidation | 24–36 mo | Sense of separateness established; on the way to object constancy; resolution of separation anxiety |

Adapted from Mahler, M. Pine, F., & Bergman, A. (1975). The psychological birth of the human infant. New York: Basic Books.

Table 8-3 Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages

| Age | Stage | Pathological Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Infancy (birth to 18 mo) | Trust vs. mistrust | Psychosis, addictions, depression |

| Early childhood (18 mo to 3 yr) | Autonomy vs. self-doubt | Paranoia, obsessions, compulsions, impulsivity |

| Late childhood (3 to 6 yr) | Initiative vs. guilt | Conversion disorder, phobias, psychosomatic disorder |

| School age (6 to 12 yr) | Industry vs. inferiority | Inertia, creative inhibition |

| Adolescence (12 to 20 yr) | Identity vs. role confusion | Delinquency, gender-related identity disorders, borderline psychotic episodes |

| Young adulthood (20 to 30 yr) | Intimacy vs. isolation | Schizoid personality |

| Adulthood (30 to 65 yr) | Generativity vs. stagnation | Midlife crisis, premature invalidism |

| Old age (65 yr to death) | Ego integrity vs. despair | Extreme alienation, despair |

Adapted from Erikson, E. (1964). Insight and responsibility. New York: W. W. Norton; Erikson, E. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton.

The job of the psychodynamic therapist is to help the person understand how fears and inhibitions in early life have led him/her to react to healthy feelings as if they were a threat and how this plays an active role in generating his/her difficulties in the present. The person inadvertently and consistently brings about consequences that are not consciously intended. The psychodynamic therapist uses interpretations to expose the person to previously avoided experiences combined with empathy in a safe therapeutic environment. Chapter 3 discusses interpretation. The focus of the interpretation depends on the school of psychodynamic thought the therapist subscribes to. This exposure is not just aimed toward intellectual understanding but emotional experiencing at a gradual pace. Re-experiencing painful affects allows adaptive processing so dissociated or disconnected memory networks can be integrated with other, more adaptive neural networks (Cozolino, 2002).

History

The history and theory of psychodynamic psychotherapy since Freud’s time is complex, and his ideas have undergone numerous permutations and iterations. This evolution has paralleled paradigm shifts in science in the 20th century, which emphasize interconnections, mutual interactions, and subjectivity of phenomenon (Curtis & Hirsch, 2003). Each psychodynamic model evolved from the others before establishing a new perspective placing different emphasis on human development and motivation for behavior. New perspectives addressed what was seen as the failure of Freud’s theory (Mitchell, 1988). These competing schools of thought—freudian, ego, self, existential, lacanian, analytic, object relations, interpersonal, relational, and intersubjective—are somewhat insular and fragmented in that each seems to take little notice of the others. Each school developed its own theoretical constructs and techniques. The following overview highlights selected theorists and does not do justice to the complexity, richness, and nuances of psychoanalytic theory.

Sigmund Freud’s classic model of psychoanalytic psychotherapy is based on drive theory; all behavior is determined by unconscious forces or instincts, either sexual or aggressive. Freud’s structural model of the id, ego, and superego explains the idea of psychic conflict. Symptoms are thought to develop through a conflict between an instinctual wish (id) and the defense against the wish (ego). The superego is part of the unconscious and is formed through internalization of moral standards of parents and society, and it acts to censor and restrain the ego. The concept of psychic determinism is embedded within this model and refers to the idea that nothing happens by chance and that everything on a person’s mind and all behavior, pathologic and nonpathologic, has a cause and is multiply determined. Freud delineated the psychosexual stages of development based on the idea that libidinal energy shifts from various erogenous zones in each stage. Freud posited that if a person had not successfully negotiated the previous stage, specific problematic character traits or psychopathology would continue throughout life (see Table 8-1).

Ego psychology and object relations theorists such as Margaret Mahler followed with increased emphasis on relationship in producing change. Mahler’s object relation theory evolved from her observations of infants and children and analysis of this qualitative data (Mahler et al., 1975). Stages of development based on separation-individuation were described, explaining how children develop a sense of identity separate from their mothers (see Table 8-2). The infant was described as being totally dependent, with relatively little self-other differentiation, and the child develops through a relationship into a separate person with a high degree of differentiation.

Klein and Fairburn combined intrapsychic theory and drive theory with the idea that the primary motivation of the child is to seek objects (Curtis & Hirsch, 2003). Object means the internalization of experiences with other people. Object relations theorists posit that people are primarily motivated to seek other people and that this is the central motivating force in development rather than drive gratification (Winnicott, 1976). Winnicott (1976) speculated that for a child to develop a healthy, genuine self, as opposed to a false self, the mother must be a “good enough mother” who relates to the child with “primary maternal preoccupation.” The child then can grow and explore without overwhelming anxiety feeling that the world is safe. The child develops a sense of “me,” and those aspects that are not part of him or her create a potential space between him/herself and the mother. This is the area of play and is an important dimension of the development of the self. Winnicott (1976) said that the therapist’s chief task is to provide such a “holding environment” for the patient so that the patient can have the opportunity to meet neglected ego needs and allow the true self to emerge. In contrast to the good enough mother, the “not good enough mother” is thought to create a dynamic in subsequent relationships in adult life, in which the person feels never good enough. Alice Miller (1981) in her widely recognized book, The Drama of the Gifted Child, describes eloquently the adverse effects of certain types of parenting on the development of the child’s true self.

Building on Freud’s ideas about intrapsychic conflict, Erik Erikson, a lay psychoanalyst, expanded the theory of development to encompass the entire life cycle. He conceptualized life as a struggle of conflicting needs in the quest toward self-actualization (Erikson, 1964). These conflicting needs revolved around the need for stability versus the need for growth at each stage of development. Table 8-3 shows Erikson’s stages of development. As we move from infancy to old age, Erikson posited that we face a stage-specific conflict that involves themes of inhibition versus desire. Although similar symptoms may be experienced in each stage, each of the eight stage-specific conflicts may have a different meaning, depending on unique issues and emotions for that particular stage, and success at resolution depends on how successfully the person has negotiated the previous stages. For example, a 21-year-old woman came to therapy after being raped in college. She had become significantly depressed and attempted suicide shortly after the rape. Her depression reflected a loss of identity that was shattered beyond repair. She had previously functioned as her parents expected her to and was generally motivated to meet others’ expectations. Her depression precipitated an exploration of her own values and who she really was, a process that gradually allowed her to rebel against the need to conform. Finding her own voice was integral to the treatment, and she eventually was able to articulate the differences between her opinions and those of her parents. Her depressive symptoms represented the conflicting need for stability and conformity versus the need for self-awareness and growth.

Significantly departing from the idea of intrapsychic conflict, Heinz Kohut developed self-psychology based on a deficit model of development. Kohut posited that the self was the central organizing frame of reference and that the self seeks out responses from others to maintain self-cohesion (Kohut & Wolf, 1978). Contrary to Freud’s conception of the individual as primarily being driven by the quest for pleasure, Kohut’s self strives for competence, self-esteem, and order, and these are the sine qua non motivators of behavior. Others serve self-object functions for the individual, and these include mirroring, idealizing, and alter-ego experiences. Individuals never lose the need for self-object experiences throughout life. If self-object experiences are less than adequate in early life, the person may later in life have difficulty with self-soothing, self-regulation, and maintenance of self-cohesion. Kohut based this idea on the clinical observation that a certain subgroup of patients developed an idiosyncratic transference in therapy, which he called the narcissistic transference. These patients, unlike the typical analytic patient, needed mirroring and idealized the analyst. Those with this type of self-pathology formed attachments based on these needs. Kohut posited that empathy played a central role in the psychotherapy of those with narcissistic psychopathology.

The relational model evolved in the 1980s from object relations, self, interpersonal, existential, and feminist models. This significant shift in the psychoanalytic paradigm changed what was called a one-person psychology to a two-person psychology (Gabbard, 2004). This awareness of two separate minds interacting with one another is also referred to as intersubjectivity. The therapist is considered a co-participant in the co-construction of the relationship, not an outside observer. It is only in the present moment as the process is unfolding that both participants’ understanding is deepened. The need for relationship derives from the physical closeness to the mother and is thought to be the prime motivator for behavior. The presence of the other is necessary and inescapable in human development and in the therapeutic relationship. Self-regulation results from mutually regulatory interactions with caretakers and evolves within the mother-infant dyad. Relational psychodynamic theory heightens our understanding about the need for attachments for psychophysiologic stability.

Schore’s (2003, 2006) neurobiologic research on attachment provides a scientific basis for relational theory and the importance of relationship to therapeutic action in psychotherapy. The growing capacity to self-regulate is contingent on transformations of underdeveloped functions that exist in the infant through early attachment experiences that assist the developing psychobiologic, homeostatic regulatory processes. Cumulative early attachment problems are thought to produce chronic dysregulation in central and autonomic arousal, with deficits in mind and body. Chapter 2 discusses the neurophysiology underlying this dysregulation. Problems in self-regulation include difficulties in tension regulation, such as addictive disorders, eating disorders, personality disorders, anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and mood disorders.

A basic tenet of the contemporary relational model is that the therapist and patient are always participating in a relational configuration and that understanding this process is how change occurs. Before relational theory, much discussion ensued about the differences between the transference relationship and the “real” relationship between the therapist and patient. The transference and the patient’s feelings toward the therapist were artifacts of the past, whereas the real relationship was what was going on in the present. In the relational model, however, this is irrelevant, because there are multiple truths, and there is no real relationship, only a co-constructed interaction that is at best subjective (Safran & Muran, 2000). This interaction coupled with mindfulness is the agent of change, and developing and repairing problems in the therapeutic alliance is considered the work of relational psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Embedded in this idea of multiple truths is the concept of multiple selves; there is no unitary true self, but each person is constructed with many self-states. Different self-states are based on the various states of consciousness that we flicker in and out of throughout the day. Chapter 2 discusses the neurophysiology supporting this idea. These shifting, multiple self-states elicit complementary self-states in others through relationship. Dissociated self-states that are experienced as potentially dangerous are kept from the person’s awareness. By “potentially dangerous,” Safran and Muran (2000) explain that these states are associated with actual traumatic experiences or disruptions of relatedness to significant others. Assisting the patient to experience and accept the various dimensions of the self through enhanced awareness of these traumatic states is considered crucial to the relational psychodynamic therapy process.

A synthesis of the literature on the relational model reveals significant differences between freudian psychodynamic psychotherapy and relational psychodynamic therapy. Table 8-4 compares and contrasts these models.

Table 8-4 Comparison of Freudian Psychodynamic and Relational Psychodynamic Therapy

| Feature | Freudian Psychodynamic | Relational Psychodynamic |

|---|---|---|

| Therapist’s role | Objective | Participant-observer |

| Perspective | One-person psychology | Two-person psychology |

| Motivation | Drives, such as sex or aggression | Emotional communication and affect regulation |

| Focus of exploration | Then-and-there; genetic roots of the problem (e.g., how a patient’s transference reaction is linked to feelings belonging to a person from the past) | Here-and-now; patient and therapist’s contributions to the interaction; patient’s experience |

| Aim | Make the unconscious conscious | Resolve ruptures in the therapeutic alliance |

| Change agent | Insight | Mindfulness |

| Symptom | Psychopathology | A communication |

| Transference | Interprets in light of the past | Cautious about generalizing to past |

| Countertransference | Caused by the patient; less disclosure by the therapist | Co-constructed; use of countertransference disclosure |

| Resistance | Intrapsychic event that involves a defense working against change | Co-constructed, unconscious rupture of the therapeutic alliance; interpersonal ruptures outside of therapy |

| Interpretation | Of wish or defense conflicts | Of alliance ruptures outside and inside of therapy |

Evidence-Based Research

Studies of the efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy are limited compared with some other psychotherapy approaches, such as CBT. The lack of studies does not demonstrate that this approach is not effective, but it may more accurately reflect the difficulties in experimental controlled design for this approach. Numerous methodologic problems for research on psychodynamic psychotherapy have been identified, because psychodynamic techniques do not lend themselves to the precision required for a clinical trial (Curtis & Hirsch, 2003; Gabbard, 2004). The problems include the following:

1. Manualized, structured protocols, such as CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), are easier to systematically evaluate.

2. There is great difficulty in randomizing subjects, which is the gold standard of experimental design. Patients who want to engage in psychodynamic psychotherapy must be motivated to engage in the self-reflected exploration needed and are self-selected.

3. If the treatment is long term, which some psychodynamic therapy is, the costs would be too great to follow patients over time.

4. Funding is lacking for studies in psychodynamic psychotherapy.

5. The complexity and variety of psychodynamic approaches and technique make adherence to a specific model for intervention in an experimental design difficult.

6. Because subjectivity and context are embedded in the psychodynamic process, it is not possible to study by traditional objective scientific inquiry.

7. Most psychodynamic research consists of case studies, which limits the ability to generalize to other situations and populations.

8. Outcomes involve internal change for psychodynamic psychotherapy, which is difficult to quantify. In any case, research in this type of therapy has only begun in earnest in the past 5 to 10 years and is relatively late on the scene of outcome studies for psychotherapy.

Probably the most complete compendium of psychoanalytic research is the book by Fonagy (2002), An Open Door Review of Outcome Studies in Psychoanalysis. Reviews of more than 80 studies conducted worldwide are included, and in general, these studies report positive results for psychoanalytic psychotherapy. One of the more notable studies included is that of Sandell and colleagues (2000). Four hundred subjects in analytically based psychotherapy were followed over 3 years, and progressive improvement in symptom measures was found. Roseborough (2006) conducted an analysis of outcomes using a single-group, within-subjects, longitudinal design in a clinic with subjects with varied diagnoses. He found that patients receiving psychodynamic psychotherapy overall made statistically significant positive changes (Roseborough, 2006). Another study of 74 randomly selected subjects with major depression compared psychodynamic psychotherapy combined with clomipramine versus clomiprimine alone. Outcomes demonstrated that the group with the combined treatment (medication plus psychotherapy) had better global functioning at discharge from the hospital and fewer days as an inpatient, fewer subsequent hospitalizations overall, and fewer lost work days 10 weeks after discharge (Burnand et al., 2002).

ce:anchor id=”p0250″/>Winston and colleagues (1994) found that subjects with personality disorders improved significantly and maintained improvement for 1.5 years on all measures after a mean of 40 sessions compared with a control group. Svartberg and colleagues (2004) also studied subjects with personality disorder, comparing psychodynamic therapy with CBT after 40 weekly sessions. The overall patient group showed, on average, statistically significant improvements on all measures during treatment and during a 2-year follow-up period. Significant changes in symptom distress after treatment were found for the group of patients who received short-term dynamic psychotherapy, but not for the CBT patients. Two years after treatment, 54% of the short-term dynamic psychotherapy patients and 42% of the CBT patients had recovered symptomatically, whereas approximately 40% of the patients in both groups had recovered in terms of interpersonal problems and personality functioning.

Many of the studies have been conducted on those who have been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD). Analysis of a randomized, controlled trial found that psychoanalytic treatment was more effective than standardized treatment for subjects with BPD in a partial hospital (Bateman & Fonagy, 2001). A Cochrane review, which included dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) and psychoanalytically day hospital therapy for subjects with BPD, suggests that the talking therapies, if available, may have considerable positive effects (Binks et al., 2006). The review concludes that the findings cannot be generalized to other populations (or groups) due to the small sample size and because these studies are often undertaken by enthusiastic pioneers in the field. However, the results indicate that people with BPD are amenable to change with psychodynamic psychotherapy. In an ongoing study comparing transference-based psychotherapy (TBP), which is psychodynamically oriented with DBT and supportive psychotherapy for subjects with BDL, TBP appeared to be beneficial (Clarkin et al., 2001).

Research on psychodynamic treatment of other populations shows mixed results. The Schiophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) report argues against the use of psychodynamic therapy in cases of schizophrenia, commenting that more trials are necessary to verify its effectiveness (Lehman & Steinwachs, 1998). The PORT recommendation is based on the opinions of clinicians rather than on empirical data. A review of current medical literature in the Cochrane database of reviews reached the conclusion that no data exist that support the idea that psychodynamic psychotherapy is effective in treating schizophrenia. The data also suggest that psychoanalysis is not effective (and possibly even detrimental) in the treatment of sex offenders (Malmberg, 2006; Malmberg & Fenton, 2001).

Psychodynamic Continuum

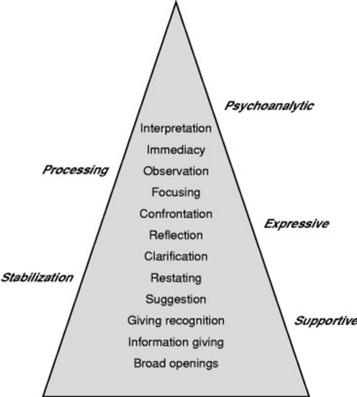

Psychodynamic psychotherapy can be seen as a continuum from supportive psychotherapy to expressive to psychoanalysis using the practice treatment hierarchy from Chapter 1, Figure 1-4, as an overall framework for practice. The goals and focus of each type of psychodynamic psychotherapy differ, with the supportive end of the continuum aimed toward restoring functioning, reducing anxiety, strengthening defenses, and more effective problem solving, whereas the psychoanalytic end of the continuum is aimed toward interpreting unconscious conflict and gaining insight (Kaplan & Sadock, 2004). Expressive and psychoanalytic therapies involve more emotional processing that alternate with periods of stabilization, and therapy often shifts back and forth along this continuum. Chapter 1 (Figure 1-6) addresses the treatment process spiral that illustrates the process of psychotherapy. The degree to which the therapy is supportive versus psychoanalytic is based on the focus on transference issues and the frequency of sessions (Gabbard, 2004). In moving toward the psychoanalytic end of the continuum, the transference interpretations increase, as do the number of sessions per week. Through transference, unconscious conflicts are illuminated and then worked through. By increasing the number of sessions per week, it is thought that the transference intensifies, which is desired in psychoanalytic psychotherapy.

Along this continuum, therapeutic communication (see Chapter 3, Figure 3-2), illustrates communication techniques appropriate for psychodynamic psychotherapy (Figure 8-2). In Chapter 3, the communication techniques considered to be more supportive are less emotionally laden and appropriate for stabilization, whereas those higher on the treatment triangle may trigger processing and implicit neural networks. Without the proper resources, this may be experienced as overwhelming and unmanageable feelings. The supportive techniques are considered to be resource building and less anxiety provoking. Supportive communication alternating with those communication techniques higher on the treatment hierarchy are appropriate for the emotional processing that occurs in expressive and psychoanalytic psychotherapies. For patients who require primarily stabilization through supportive psychodynamic psychotherapy, the communication techniques toward the lower level of the treatment hierarchy are most often used.

Case Formulation

In order for the APPN to decide on a relevant therapeutic focus, realistic expectations of treatment, and the appropriate type of psychodynamic psychotherapy to use, a dynamic case formulation is essential. In general, the shorter the length of the psychotherapy, the more intense the pressure to determine a therapeutic focus, and this is done through a psychodynamic formulation. Safran and Muran (2000) state, “It is the establishment of a dynamic focus and the consistent interpretation of that focus over time, as it emerges in a variety of different contexts that facilitates the working thorough process and allows the client to integrate treatment changes into his/her everyday life” (p. 178). As addressed in Chapter 1, Figure 1-4, the hierarchy of treatment aims is helpful in this regard, but a more sophisticated psychodynamic understanding of development and defenses further refines treatment choice and informs the work of psychodynamic psychotherapy. The case formulation identifies a central issue that underlies the person’s presenting problem that is related to the person’s early developmental history. This involves conceptualizing presenting issues developmentally and understanding intrapsychic conflict. Three personality organization levels have been identified—neurotic to healthy, borderline, and psychotic—based on a synthesis of major developmental theories (McWilliams, 1994) (Figure 8-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree